Hmm. I'm sorry to have to say this, but I think this post is not very good.

In summary, I would say that this article is discussing a set of very common, well-trodden issues (Bayesian model checking/expansion/selection, generally speaking problems of insufficient 'model space') in a very nontechnical way (which is of course a fine approach on its own, but it's strange that the thing that this is talking about is not referenced or referred to as the thing it's called anywhere, instead everything here is presented as if it was a novel first-principles contribution), in such a way that proposes the most wishy-washy solution to the problem (just ignoring it) without reference to any alternatives and without really discussing the disadvantages of this approach.

To go line by line: first, though the title and the framing of this article surround priors, as you kind of point out, the prior isn't really what's changing here, but the likelihood (and the part of the prior that interacts with it). You can consider yourself to have, in theory, a larger prior that you just weren't aware you should be considering. So, the problem that this is dealing with is the classic "I don't actually believe my likelihood is correct" model, for which there are a billion proposed solutions, which you don't really touch on for some reason (to name a few, "M-open" analyses, everything in the Gelman BDA chapter on model expansion, nonparametric methods which to be fair you hint at with 'infinite-dimensional', etc).

To briefly explain some of these: one classic approach is to consider your prior attempt some model , with some prior probability, and your next one an , and your final posterior will be an averaging out of each, with some prior model credences. In this specific case, you could probably nest both of the likelihoods into a single model, somehow. The most common applied approach, as many have pointed out, is to just split the data and do whatever exploratory analyses you want on the head of the table or some such approach.

The problem with this classic solving-by-not-solving approach is that, well, you are not being an actual Bayesian anymore; if your (technical) prior depends on observing the data, your procedure no longer actually follows the laws of probability, no longer benefits from Cox's theorem, has no guarantee relating to Dutch books and does not result in decision-optimal rules (roughly the same reasons orthodox Bayesians reject empirical-Bayes methods, which are a non-Bayesian half-solution to this issue, kind of). So, well, I don't see the point.

There are good ways and bad ways to be approximately Bayesian, and this particular one seems no good to me, at least without further argument (especially when avoiding it is so easy and common. Just data-split!). Double-counting methods always look good when you are in a thought experiment and are doubling down on what you know to be the right answer, the problem is that they are doubling down on the wrong answers for no reason, too; it seems perfectly reasonable to me to admit that 50/50 posterior after seeing just a little bit of data, then some model refinement happens, and your posterior upon seeing the full data looks more 'reasonable'.

So, I don't know. These are good (classic) questions, but I am forced to disagree with the notion that this is a good answer.

Thanks for the reply, sorry I just saw this. It was indeed my goal to talk about existing ideas in a nontechnical way, which is why I didn't frame things in terms of model expansion, etc.. Beyond that however, I am confused by your reply, as it seems to make little contact with my intended argument. You state that I recommend "just ignoring" the issue, and suggest that I endorse double-counting as OK. Can you explain what parts of the post led you to believe that was my recommendation? Because that is very much not my intended message!

(I stress that I'm not trying to be snarky. The goal of the post is to be a non-technical explanation, and I don't want to change that. But if the post reads as you suggest, I interpret that as a failure of the post, and I'd like to fix that.)

Thanks for replying. Given that it's been a month, sadly, I don't fully remember all the details of why I wrote what I wrote in my initial comment, but I'll try to roughly rewrite my objections in a more specific way so that you get where it makes contact with your post ("if I had more time, I would've written a shorter letter"). Forgive me if it was somehow hard to understand, English is my second language.

My first issue: the post is titled "Good if make prior after data instead of before". Yet, the post's driving example is a situation where the (marginal) prior probability of what you're interested in doesn't actually change, but instead is coupled to a larger model with a larger probability space where the likelihood is different at these different points. So, what you're talking about isn't really post-hoc changes to the prior, but something like model expansion, as you write in the comment.

In the context of methodologies for Bayesian model expansion, there is a lot of controversy and much ink has been spilled, because being ad-hoc and implicitly accepting a data-driven prior/selected model leads to incoherence; the decision-procedure you now derive from this is not actually Bayesian in the sense that it satisfies all the nice properties people expect of Bayesian decision rules and Bayesian reasoning, it just vaguely follows Bayes's rule for conditioning. When you write

So the only practical way to get good results is to first look at the data to figure out what categories are important, and then to ask yourself how likely you would have said those categories were, if you hadn’t yet seen any of the evidence.

you are sidestepping all of these issues (what I called "solving by not solving") and accepting incoherence as OK. And, well, this can be a fine approach - being approximately incoherent can be approximately no problem. But, I think that the post not only fails to address the negatives of this particular approach, positioning it as kind of the only thing you can reasonably do (which is in itself a sufficiently large problem), but fails to consider any other ones (A classic objection to this type of methodology in a canonical introductory textbook, providing one of the alternatives I mentioned, is here, for example, in which the idea is to have a model flexible and general enough that it can learn in essentially any situation; I mentioned other methods in the comment). Do you not see the incoherence of a data-driven prior as bad somehow?

To be clear, the other approach you consider of "never change your model/prior after seeing the data, even if your model makes no sense, your posterior is stuck as it is" is also bad for all the obvious model misspecification reasons. But, at the very least it is coherent (and, of course, by data-splitting you get to enjoy this coherency without being rigid at the cost of a little data, so there's another approach, much less technical to explain than the nonparametric approach mentioned prior). This is my main problem with the article, really: it proposes just this one idea among several without discussing its positives or negatives in relation to any of the other ones.

My point with this article endorsing "double-counting" is that one way in which this approach (roughly summarized as "construct the model after seeing the data, pretending like you haven't seen the data") is that, in comparison to either a nonparametric approach or some M-open idea like model mixing or stacking, it will privilege the particular model which you happened to construct on the basis of the data more so than a fully coherent theoretical approach.

An easy way to see this is to imagine if you were to try this approach while being knowledgeable about all possible models you could have picked (i. e. in model averaging, they wave at a similar critique to this idea in this other intro); in this representation, instead of observing the data and updating yourself towards one particular model representation which fits best with the data, your method is to set one model's probability to 1 and all others to zero, which is a rather extreme version of double-counting[1].

So, in my perspective, a good version of this article would not talk about anything being "the only practical way to get good results", and would situate this idea alongside all the other ones in this vein which have been discussed for decades, or at least sort of gestures at the more common approaches you consider sensible and that you think you can explain nontechnically (hopefully referenced by their names), and at the bare minimum it should explain the pros and cons of what it advocates with more balance. Admittedly, this is a much harder article to write, because the issue has become nuanced, and I would not know how to write it non-technically, at least immediately. However, the issue seems to be nuanced, at least to me, and this level of simplification misleads more than it helps.

- ^

In the original comment I decided to talk more about how easy it is to make double-counting methods seem arbitrarily good by way of constructing examples where you know the truth in advance, since of course it looks better if you get to the truth twice as fast, but the double-counting when the data happens to be misleading gets you doubly wrong too, but this objection seems kind of petty and irrelevant compared to the other ones, in hindsight.

Bayes Theorem is so simple that it's felt like if you get it, say if you're gone through the Bayes rule guide, then you get it. Posts like Why I’m not a Bayesian and this one show that there's more to think about. That's pretty cool when you are a Bayesian and it's a cornerstone of your epistemology. Good job here.

A question for the author, is the position here something like the actual data/question at hand influences how you should calculate your priors, but only previously held info should be fed into the calculation?

I sort of flicked past the equations, seeing that they were vaguely intuitive and kinda redundant to the text, until the first Huh heading. At that point, I sighed deeply and headed back to the top to actually read the equations. Will report back.

Reporting back: yep worth reading the equations slowly

This is great. I don't remember the last time a post made me flip so hard from "the thesis is obviously false" to "the thesis is obviously true"! And not just because I didn't understand it, but also because I learned a thing. (Tho part was a pedagogically useful misunderstanding.)

This post seems to fundamentally misunderstand how Bayesian reasoning works.

First of all, the opening "paradox" isn't one. If you have an inconclusive prior belief, and then you apply inconclusive data, you should have an inconclusive result. That's not weird. Why is it surprising?

Secondly, the argument that follows is adding more conditions to the thesis that muddy the waters. P(A, B) is always less than P(A) if P(B) > 0. The probability that a coin lands on heads and that it's tuesday is always less than the probability that a coin lands on heads. That fact does not tell you anything about the probability of the coin itself, and trying to include the fact that coins land face up on tuesdays less than coins land face up into your beliefs on the nature of coins, you will go mad because those things are not related and the probability relationships are tautological.

Thirdly, the post ignores marginal likelihood, the denominator of Bayes theorem. If there are alternative explanations for evidence[1], then it is weak evidence, and should not result in a large change in belief. It's not just about how likely the evidence is given a thesis, it's about how likely some evidence is given that thesis as opposed compared to all others. P(cough|COVID-19) is very high, almost 1. But that's not really worth much because P(cough|any other respiratory disease) is also very high, almost 1, and 1/1=1, so the posterior = the prior.

Finally and most importantly, the thesis is that priors should include past evidence, which is like... yeah. That's how bayesianism works. You calculate the posterior given a new piece of data, and that posterior becomes your prior for the next piece of data. This is Bayesian Updating.

When you want to decide whether to believe something, you don't have to start from the most naive argument from first principles every single time. Beliefs are refined over time by evidence. When you see new evidence, your reasoning doesn't start from what you knew when you were a baby, it starts from what you knew the moment before exposure to new evidence.

- For example, parallax making objects in narrow FOV videos appear to look faster than they really are.

In the "go fast" video you linked, the object is laser-rangefinder measured to be 3.4 miles away from the camera. (that sounds like a big distance, but in the aviation world it is very close. If the object had a TCAS transponder they would have been getting a collision alarm).

Their altitude is 25,000 feet, while the camera is at a downward angle of -25 degrees. Some simple SOHCAHTOA trig tells us the background is 11.1 miles away, almost 4x more distant than the object itself, so of course the background moves fast in a LITENING pod's 1 degree wide NAR mode FOV.

They are also closing on it (Vc=220, distance to the object is closing at 220 knots) and passing it (bearing changes from 40 degrees left to 60 degrees left). They struggle to lock onto it with the camera because they are going fast, the object is very close, and the field of view is very narrow, which put together creates a nightmare scenario for getting an optical spot track, like hitting a mailbox with a dart thrown from a moving car, I speak from experience using these pods.

The video is completely consistent with the object in question being a balloon blowing in the wind.

Bringing it all back, the marginal likelihood of such a video existing P(video | no aliens) is 100%, so even if P(video | aliens) is also 100%, the posterior = the prior, because the video is poor evidence.

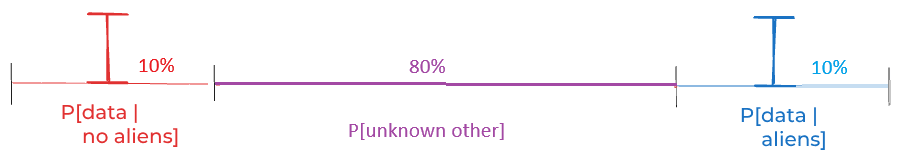

The 5th figure is incorrect and should be like what I show here. Then you will not get the nonsensical P[data|aliens] = 50%.

There are two kinds of errors the piece makes:

1. Probabilities do not add to 100%, which is the one I just pointed out.

2. Probabilities can be quite far off. The Baysian method assumes you can get close, and refines the probability. If you cannot get close, i.e. if initial data samples are far off the assumed probability, then the Baysian method does not apply and you'll have to use the Gaussian method, which requires a lot more samples.

Applying Gaussian reasoning to UAP problem:

1. There are 1.5 million pilots in the world (source: Google)

2. 800 official reports to Pentagon's AARO investigation => 800/1,500,000 = 0.053% probability of something that appears unnatural based on current understanding. P[aliens]<<0.053% in light of missing artifacts.

3. 120,000 sightings including non-pilots (assumed to have less expertise) => 8% probability of something that appears to non-experts as unnatural, so a much lower confidence number, but it explains the widespread "belief" in UFO/UAP.

Other Possibilities P[unknown other]

The author divides up possibility space into 4 categories. An interesting one to expand further is "There are aliens. But they stay hidden until humans get interested in space travel. And after that, they let humans take confusing grainy videos." In fact there were unnatural phenomena apparently seen earlier, which were identified tentatively as...

1. evidence for survival of death (seeing ghosts => ceremonial burian with artifacts needed in afterlife)

2. evidence for "High Gods" or demons

3. dreams, visions, hallucinations (not a popular majority explanation)

These are the priors of H. Sapiens collectively, and as data is being collected from H. Sapiens (mostly), they should be included in analytical priors regardless of the opinion of the investigator - because they are the opinions of the data source and inseparable from the data.

A very interesting side point from Hunter-Gatherers and the Origins of Religion - PubMed is that while many superstitious beliefs evolve naturally, High Gods do not fit the pattern of naturally evolved beliefs. They were produced or imposed in some other way. Either by high gods themselves, or by humans on other humans. Either one fits into the P[unknown other] category. You can of course dismiss this or assign P approaching 0. But your argument will appear invalid to 80% of Americans (and much of the rest of the world). Perhaps you do not care about them. But if you are going to sell to them or your work is supported by grants from them, you have a very limited future if you do not take beliefs you do not share into account. The simple solution is to just discard the Baysian method as inapplicable when the data source itself has a wide variety of undecidable beliefs.

Undecidable meaning you cannot get them to agree because each belief if used as a prior causes data to be interpreted in a way to reinforce the belief.

The figure you are referring to does not need to add up to 100%, since it is showing P[data | aliens] and P[data | no aliens].

P[data | aliens] and P[not data | aliens] need to add to 100%, but that is not on the graph.

As an extreme case where P[A | B] + P[A | C] != 1, consider A = coin did not land on its edge, B = the coin is ordinary, C = the coin is weighted to land heads twice as often as tails.

Then P[A | B] = 0.9999 and P[A | C] = 0.9999 would be reasonable values.

Pragmatically, in data analysis tasks, what you do is a separate preliminary data collection that you only use to decide the priors (the whole data analysis structure, really) and then collect data again on which you run the actual analysis. This applies to non-Bayesian data analysis as well. This duplicated data collection helps you stay objective and not sneak into the prior any information which would not be Bayes-kosher to glean from the data. Of course it's less efficient because you are not using all the data in the final analysis.

I liked this!

Isn’t this post an elaborate way of saying that today’s posteriors are tomorrow’s priors?

As in- all posteriors eventually get baked into the prior.

How I would pack in one sentence the intuition for why 'changing priors' is ok: "Sometimes the number you wrote down as your prior is not your real prior, and looking at the data helps you sort that out."

Yes, that's how Bayesianism is supposed to work. It's called Bayesian Updating.

You don't wake up every day with a child's naivete about whether the sun will rise or not, you have a prior belief that is refined by knowledge combined with the weight of previous evidence.

Then, upon observing that the sun did in fact rise on this new morning, your belief that the sun rises every day gets that much stronger going into the next day.

Interestingly, this is broadly consistent with Leonard Savage's view of priors, at least according to Ken Binmore https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41412-017-0056-1

Everybody would presumably agree that it would be better for Alice to consult her gut feelings when she has more evidence rather than less. For each possible future course of events, she should therefore ask herself what subjective probabilities her gut would come up with after experiencing these events. In the likely event that these posterior probabilities turn out to be inconsistent with each other, she should then take account of the confidence she has in her current snap judgements to massage her posterior probabilities until they become consistent. After the massaging is over, Alice would have eliminated the possibility of being surprised by a black-swan event. She would already have taken account of the impact that all future information might have on the unformalized internal model that she uses in determining her beliefs. She would not only have adjusted the subjective probabilities she attaches to events in the small world with which she begins, but potentially expanded her state space to a larger small world in light of the new possibilities that black-swan events commonly suggest (Gillies 2001; Williamson 2003).

The end-product of Alice’s massaging process is therefore a bunch of consistent posteriors defined on a state space that she will never need to revise. With the consistency axioms of Savage’s theory of subjective probability, her massaged posteriors can all be deduced by Bayes’ rule from a single prior. In this story, Bayes’ rule is therefore reduced to a mere book-keeping tool that saves Alice from having to remember all her massaged posterior probabilities. The prior that Savage attributes to Alice therefore squeezes all the juice that can be squeezed from the disorderly set of impressions with which she comes to the problem.

In short, the procedure is something like:

- Compute the "posteriors" for all possible future evidence (in your case, this is done the Bayesian way, but in general doesn't have to be).

- Notice the inconsistencies in those "posteriors" and ways in which they seem off.

- Coherentify/massage those posteriors until they start making sense.

- In particular, unconditioning each posterior on its piece of evidence should get you back at the same prior probability.

Experimentally, can I say frequentist actually have a better representation of the "event" to observe? It doesn't require the "observer" to make any prior assertion about the distribution. This is especially true when we are gathering more and more data with ease. Those data might not be of high quality. But the volume can simply "wash out" those quality issues as long as the collection method is not biased. I always have this nagging feeling that bayesian is not a very practical tool when it comes to experimental science.

They say you’re supposed to choose your prior in advance. That’s why it’s called a “prior”. First, you’re supposed to say say how plausible different things are, and then you update your beliefs based on what you see in the world.

For example, currently you are—I assume—trying to decide if you should stop reading this post and do something else with your life. If you’ve read this blog before, then lurking somewhere in your mind is some prior for how often my posts are good. For the sake of argument, let’s say you think 25% of my posts are funny and insightful and 75% are boring and worthless.

OK. But now here you are reading these words. If they seem bad/good, then that raises the odds that this particular post is worthless/non-worthless. For the sake of argument again, say you find these words mildly promising, meaning that a good post is 1.5× more likely than a worthless post to contain words with this level of quality.

If you combine those two assumptions, that implies that the probability that this particular post is good is 33.3%. That’s true because the red rectangle below has half the area of the blue one, and thus the probability that this post is good should be half the probability that it’s bad (33.3% vs. 66.6%)

(Why half the area? Because the red rectangle is ⅓ as wide and ³⁄₂ as tall as the blue one and ⅓ × ³⁄₂ = ½. If you only trust equations, click here for equations.)(Why half the area? Because the red rectangle is ⅓ as wide and ³⁄₂ as tall as the blue one and ⅓ × ³⁄₂ = ½. If you only trust equations, click here for equations.)

It’s easiest to calculate the ratio of the odds that the post is good versus bad, namely

It follows that

and thus that

Alternatively, if you insist on using Bayes’ equation:

Theoretically, when you chose your prior that 25% of dynomight posts are good, that was supposed to reflect all the information you encountered in life before reading this post. Changing that number based on information contained in this post wouldn’t make any sense, because that information is supposed to be reflected in the second step when you choose your likelihood

p[good | words]. Changing your prior based on this post would amount to “double-counting”.In theory, that’s right. It’s also right in practice for the above example, and for the similar cute little examples you find in textbooks.

But for real problems, I’ve come to believe that refusing to change your prior after you see the data often leads to tragedy. The reason is that in real problems, things are rarely just “good” or “bad”, “true” or “false”. Instead, truth comes in an infinite number of varieties. And you often can’t predict which of these varieties matter until after you’ve seen the data.

Aliens

Let me show you what I mean. Say you’re wondering if there are aliens on Earth. As far as we know, there’s no reason aliens shouldn’t have emerged out of the random swirling of molecules on some other planet, developed a technological civilization, built spaceships, and shown up here. So it seems reasonable to choose a prior it’s equally plausible that there are aliens or that there are not, i.e. that

Meanwhile, here on our actual world, we have lots of weird alien-esque evidence, like the Gimbal video, the Go Fast video, the FLIR1 video, the Wow! signal, government reports on unidentified aerial phenomena, and lots of pilots that report seeing “tic-tacs” fly around in physically impossible ways. Call all that stuff

data. If aliens weren’t here, then it seems hard to explain all that stuff. So it seems likeP[data | no aliens]should be some low number.On the other hand, if aliens were here, then why don’t we ever get a good image? Why are there endless confusing reports and rumors and grainy videos, but never a single clear close-up high-resolution video, and never any alien debris found by some random person on the ground? That also seems hard to explain if aliens were here. So I think

P[data | aliens]should also be some low number. For the sake of simplicity, let’s call it a wash and assume thatSince neither the prior nor the data see any difference between aliens and no-aliens, the posterior probability is

See the problem?

(Click here for math.)

Observe that

where the last line follows from the fact that

P[aliens] ≈ P[no aliens]andP[data | aliens] ≈ P[data | no aliens]. Thus we have thatWe’re friends. We respect each other. So let’s not argue about if my starting assumptions are good. They’re my assumptions. I like them. And yet the final conclusion seems insane to me. What went wrong?

Assuming I didn’t screw up the math (I didn’t), the obvious explanation is that I’m experiencing cognitive dissonance as a result of a poor decision on my part to adopt a set of mutually contradictory beliefs. Say you claim that Alice is taller than Bob and Bob is taller than Carlos, but you deny that Alice is taller than Carlos. If so, that would mean that you’re confused, not that you’ve discovered some interesting paradox.

Perhaps if I believe that

P[aliens] ≈ P[no aliens]and thatP[data | aliens] ≈ P[data | no aliens], then I must accept thatP[aliens | data] ≈ P[no aliens | data]. Maybe rejecting that conclusion just means I have some personal issues I need to work on.I deny that explanation. I deny it! Or, at least, I deny that’s it’s most helpful way to think about this situation. To see why, let’s build a second model.

More aliens

Here’s a trivial observation that turns out to be important: “There are aliens” isn’t a single thing. There could be furry aliens, slimy aliens, aliens that like synthwave music, etc. When I stated my prior, I could have given different probabilities to each of those cases. But if I had, it wouldn’t have changed anything, because there’s no reason to think that furry vs. slimy aliens would have any difference in their eagerness to travel to ape-planets and fly around in physically impossible tic-tacs.

But suppose I had divided up the state of the world into these four possibilities:

No aliens + normal peopleNo aliens + weird peopleNormal aliensWeird aliensIf I had broken things down that way, I might have chosen this prior:

Now, let’s think about the empirical evidence again. It’s incompatible with

no aliens + normal people, since if there were no aliens, then normal people wouldn’t hallucinate flying tic-tacs. The evidence is also incompatible withnormal alienssince is those kinds of aliens were around they would make their existence obvious. However, the evidence fits pretty well withweird aliensand also withno aliens + weird people.So, a reasonable model would be

If we combine those assumptions, now we only get a 10% posterior probability of aliens.

Now the results seem non-insane.

(math)

(math)

To see why, first note that

since both

normal aliensandno aliens + normal peoplehave near-zero probability of producing the observed data.Meanwhile,

where the second equality follows from the fact that the data is assumed to be equally likely under

no aliens + weird peopleandweird peopleIt follows that

and so

Huh?

I hope you are now confused. If not, let me lay out what’s strange: The priors for the two above models both say that there’s a 50% chance of aliens. The first prior wasn’t wrong, it was just less detailed than the second one.

That’s weird, because the second prior seemed to lead to completely different predictions. If a prior is non-wrong and the math is non-wrong, shouldn’t your answers be non-wrong? What the hell?

The simple explanation is that I’ve been lying to you a little bit. Take any situation where you’re trying to determine the truth of anything. Then there’s some space of things that could be true.

In some cases, this space is finite. If you’ve got a single tritium atom and you wait a year, either the atom decays or it doesn’t. But in most cases, there’s a large or infinite space of possibilities. Instead of you just being “sick” or “not sick”, you could be “high temperature but in good spirits” or “seems fine except won’t stop eating onions”.

(Usually the space of things that could be true isn’t easy to map to a small 1-D interval. I’m drawing like that for the sake of visualization, but really you should think of it as some high-dimensional space, or even an infinite dimensional space.)

In the case of aliens, the space of things that could be true might include, “There are lots of slimy aliens and a small number of furry aliens and the slimy aliens are really shy and the furry aliens are afraid of squirrels.” So, in principle, what you should do is divide up the space of things that might be true into tons of extremely detailed things and give a probability to each.

Often, the space of things that could be true is infinite. So theoretically, if you really want to do things by the book, what you should really do is specify how plausible each of those (infinite) possibilities is.

After you’ve done that, you can look at the data. For each thing that could be true, you need to think about the probability of the data. Since there’s an infinite number of things that could be true, that’s an infinite number of probabilities you need to specify. You could picture it as some curve like this:

(That’s a generic curve, not one for aliens.)

To me, this is the most underrated problem with applying Bayesian reasoning to complex real-world situations: In practice, there are an infinite number of things that can be true. It’s a lot of work to specify prior probabilities for an infinite number of things. And it’s also a lot of work to specify the likelihood of your data given an infinite number of things.

So what do we do in practice? We simplify, usually by limiting creating grouping the space of things that could be true into some small number of discrete categories. For the above curve, you might break things down into these four equally-plausible possibilities.

Then you might estimate these data probabilities for each of those possibilities.

Then you could put those together to get this posterior:

That’s not bad. But it is just an approximation. Your “real” posterior probabilities correspond to these areas:

That approximation was pretty good. But the reason it was good is that we started out with a good discretization of the space of things that might be true: One where the likelihood of the data didn’t vary too much for the different possibilities inside of

A,B,C, andD. Imagine the likelihood of the data—if you were able to think about all the infinite possibilities one by one—looked like this:This is dangerous. The problem is that you can’t actually think about all those infinite possibilities. When you think about four four discrete possibilities, you might estimate some likelihood that looks like this:

If you did that, that would lead to you underestimating the probability of

A,B, andC, and overestimating the probability ofD.This is where my first model of aliens went wrong. My prior

P[aliens]was not wrong. (Not to me.) The mistake was in assigning the same value toP[data | aliens]andP[data | no aliens]. Sure, I think the probability of all our alien-esque data is equally likely given aliens and given no-aliens. But that’s only true for certain kinds of aliens, and certain kinds of no-aliens. And my prior for those kinds of aliens is much lower than for those kinds of non-aliens.Technically, the fix to the first model is simple: Make

P[data | aliens]lower. But the reason it’s lower is that I have additional prior information that I forgot to include in my original prior. If I just assert thatP[data | aliens]is much lower thanP[data | no aliens]then the whole formal Bayesian thing isn’t actually doing very much—I might as well just state that I thinkP[aliens | data]is low. If I want to formally justify whyP[data | aliens]should be lower, that requires a messy recursive procedure where I sort of add that missing prior information and then integrate it out when computing the data likelihood.(math)

Mathematically,

But now I have to give a detailed prior anyway. So what was the point of starting with a simple one?

I don’t think that technical fix is very good. While it’s technically correct (har-har) it’s very unintuitive. The better solution is what I did in the second model: To create a finer categorization of the space of things that might be true, such that the probability of the data is constant-ish for each term.

The thing is: Such a categorization depends on the data. Without seeing the actual data in our world, I would never have predicted that we would have so many pilots that report seeing tic-tacs. So I would never have predicted that I should have categories that are based on how much people might hallucinate evidence or how much aliens like to mess with us. So the only practical way to get good results is to first look at the data to figure out what categories are important, and then to ask yourself how likely you would have said those categories were, if you hadn’t yet seen any of the evidence.