The epistemics here are fantastic and if I could I'd make it a featured article. Definitely critical for any world modelling.

However, the trust section heavily features declining trust in institutions and public opinion as examples. I don't think those are good examples, since it could indicate that people are becoming more aware of institutional realities and election dynamics, such as Watergate, the War on Terror, or more people noticing things that seem "off" about the idea of democracy. Historically, large proportions of people became pessimistic about institutions in China and the Soviet Union after periods of economic hardship and political turmoil, decades before the first social media company became large enough to start seeing IRL communication as a competitor.

Which trust metrics would you instead use? The Gallup numbers are an aggregate of trust across many spheres by the way, and include areas as distant from each other as healthcare to church to Congress. While a crisis may certainly cause distrust in the state, the decline of trust has affected virtually every sphere of social life which points toward a more systematic chipping away across the board. Because of this, I would say the catalyst is a different kind of (online) sociability altogether that is taking root today.

Entertainment (enjoyment, the authentic self) and socializing separated. People watched TV alone, and then people gamed alone and then people scrolled social media together but not really and they were still basically alone.

I think it's fairly likely that the pattern will be interrupted with VR. The reasons are dumb. VR headsets package in good microphones and spacialized audio makes talking in groups fun again. We'll start to see better team games, or just social venues where people mix and talk for its own sake. Then the social online world will be a lot more enticing.

People used to game together. These days, you can't even put a chat window in your online card game because you have to hire moderators to deal with people being assholes to each other and/or would-be child molesters, and that's a whole lot more expensive than just not letting players talk to each other. Unless you're World of Warcraft, it just doesn't pay.

Another data point on this theory. When I was a child "computer games" meant 5 overexcited children screaming and shoving one another off a sofa while at any one time 4 out of 5 of them were nominally playing on the nintendo (mario kart and party were particularly popular). This clearly shifted a lot, because around 2018 I remember returning a new halo game when I found out it couldn't do split-screen. (It honestly never occurred to me to check, a shooter without split screen just feels, awful).

To me, the new "bowling alone" is "FPS without split screen".

Meanwhile, split-screen seems to me to be such a patently horrible way to play an FPS that I can’t imagine anyone liking it (and I’ve been playing FPSes since FPSes existed).

Large language models may soon (if not already) make it much easier and cheaper to moderate such spaces, so maybe we'll see a resurgence of that?

The idea that placing a helmet over one's head that obscures visual and audio perception of the real world will somehow interrupt the separation of socialization assumes that digital socialization is a replacement for or at least some kind of remedy to not having IRL interactions. To me this seems an exacerbation of the problem, not an alleviation.

Seems to be the same in many other countries, actually. In East Asia, these trends are especially prevalent.

This unfortunately is also from more of a pre-social media period than I would hope for, but Putnam’s other book (really a collection of essays by people more knowledgable on specific countries) Democracies in Flux from 2002 (https://academic.oup.com/book/8126) looks at similar trends across 8 countries: Australia, France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, Spain, Sweden, and the United States. To be clear, this is most focused on the aspects of social capital one would expect to be related to the functioning of democracy like trust and institutional memberships.

Their overall findings are that the declines seen in the US are less uniformly reflected elsewhere than I predicted prior to reading it, and that it’s also less clear than I predicted what relationship this has to functioning of democracy (again, this is most focused on measures of social capital most plausibly related to democracy). Overall, I recall coming away thinking imputing trends from the US onto other countries might paint an overly bleak picture of social capital trends, and that the causal link from declining social capital to effects on democracy was less certain than I previously thought.

That isn’t to say things are going wonderfully everywhere else, just that anchoring to the US may paint an overly bleak picture.

I don’t want to wholesale endorse this discussion of the book since it’s been a year or two since I read the original, but this seems like a reasonable summary I found for folks who are curious: https://www.beyondintractability.org/bksum/putnam-democracies.

I’d be curious to see any research folks have that take a comparative lens that are more recent, or that more specially focus on the social/emotional impacts more!

Have you considered that signaling could play a large part into this? A European friend of mine once said, "people in the US try to do everything in high school." Because, to get into a top undergraduate program, Americans have to signal very hard. Worse, a master's degree is quickly becoming the new high school diploma, due to signaling to employers.

When kids are spending their lives trying to signal stronger, it's a lot harder to balance it with friends. It used to be dating as an undergraduate made sense--people would actually get married during or out of college! Now, it makes less sense to date for a year or two and try to maintain a long-distance relationship as you split off into different PhD programs.

Maybe, that makes sense to me. As an offshoot of that (sort of), I would also say on the internet really produces so much FOMO - and a lot of people feel resentment over that, especially coupled with loneliness nowadays. Browsing social media just makes so many people feel worse.

So, people are signaling more and those "left out" feel worthless amid FOMO as if they are behind or 'not living their best life.'

I suspect some of this is tied into the increasing sense of interdependence and the reality that there are different trust systems that people use. Being bombarded with reminders that you are defendant on people who use very different trust systems is inherently anxiety producing and the increasing pace of information flow is certain to exacerbate that.

Another facet may be that big projects, while rarely economically efficient, may have a psychological grandeur that people crave. Note William James search for a "moral equivalent to war" in that the psychological yearning for achievement, sacrifice, and victory is inherently human and being awash in reminders of how others achieve and of how pampered one's one life is likely to sap any sense of achievement.

the psychological yearning for achievement, sacrifice, and victory

Yeah, how do I find a place in the social fabric and build enough of a sense of self-esteem to put myself out there if almost all work that I admire is done by a very small percentage of freakishly talented IP producers that I'm unlikely to ever be a part of? And even if I am going to be one of them, how do I survive the 25 years of hazing society puts me through before I make it there?

Curated. I've had a sense of some kind of massive societal change happening. I too read Bowling Alone a few years ago and remember being impressed by it's epistemic framing but disappointed that it was 2 decades old. Seeing more concrete data about that feels useful to me orienting to the world.

(I am, as always, interested in people digging into the details of the data and seeing whether it all checks out, whether some bits are misleading, etc)

Bizarly, for people whose tendencies were to the schizoid anyway and regardless of sociological changes - this might be midly comforting. Your plight will always seem somewhat more bearable when it is shared by many.

Also: the fact that people now move out later might be a kind of disguised compliment, or at least nod, to better quality parents-children relationships. While I was never particularly resourceful or independent, I couldn't wait to move out - but that was not necessarily for the right reasons.

Finally - one potentially interesting way of looking at the increasingly exacerbated partisanship / level of political division across the country might be as a sort of last ditch attempt to fight desocialization. When no community remains the "I really don't like liberals" and "I really don't like conservatives" groups of kindred spirits offer what might be the last credible alternative to it.

Atomization and loneliness is a direct outcome of modernity and urbanization. It’s the job of corporations is to fill niches for profit, including social niches. substituting your community for profit is the natural progression of capitalism. Social media is directly competing with your time otherwise spent with friends and family. Real Companionship directly competes with things like onlyfans and streamers. All transactions need to be commoditized. If you want to say hi to your friends you must do it through a corporation!

At the end of the line, we’ll all be technologically self sufficient, perfectly atomized, each living in our own universe (hence the multiverse).

Share of individuals under age 30 who report who report zero opposite sex sexual partners since they turned 30.

Wait, did that survey account for sexual orientation? Because if it didn't, it's essentially worthless.

Why? Roughly 97% of people are heterosexual. I don't see how sexual orientation could massively skew the results.

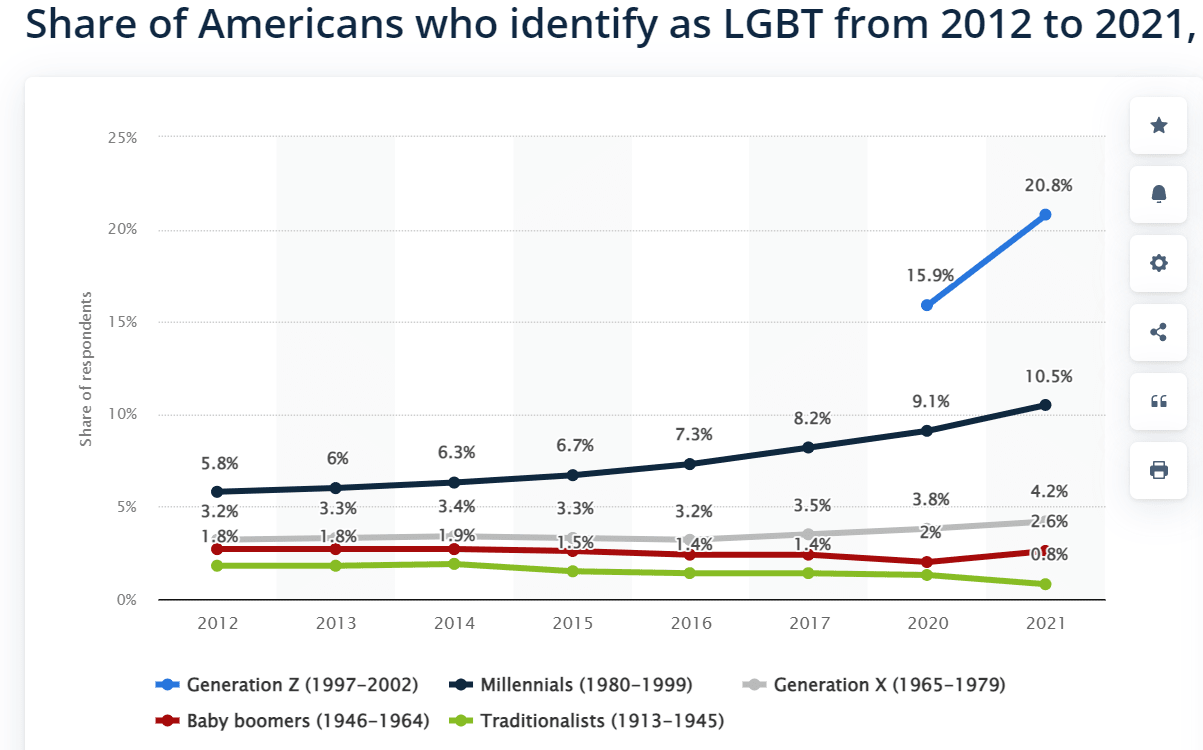

20% of Gen Z Americans seem to identify as LGBT, so increasing LGBT rates could explain a lot of the variance- especially for women (where there's less variance to explain and more LGBT). Correction: (But it does seem that the B (57%) is more common than the LGT (https://news.gallup.com/poll/389792/lgbt-identification-ticks-up.aspx), which might make it less explanatory - but there could be a reasonable proportion of bi young people avoiding hetero relationships).

That is... kinda shocking to me, tbh. Why would it have increased that much? This has to be cultural influence.

Humans generally crave acceptance by peer groups and are highly influenceable, this is more true of women than men (higher trait agreeableness), likely for evolutionary reasons.

As media and academia shifted strongly towards messaging and positively representing LGBT over last 20-30 years, reinforced by social media with a degree of capture of algorithmic controls be people with strongly pro-LGBT views, they have likely pulled means beliefs and expressed behaviours beyond what would perhaps be innately normal in a more neutral non-proselytising environment absent the environmental pressures they impose.

International variance in levels of LGBT-ness in different cultures is high even amongst countries where social penalties are (probably?) low. The cultural promotion aspect is clearly powerful.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1270143/lgbt-identification-worldwide-country/

The obvious explanation would be "because LGBT people are less pressured to present as heterosexual than they used to be".

I don't think it is plausible that there is such a high natural rate of non-cishet people in the human species. I think this is an example of "Born This Way" being bullshit and culture actually modifying people's sexual and gender identity during sensitive imprinting periods in childhood. (Before you call me a homophobe, I'm LGBT myself, and I am pretty sure it actually is partly because of childhood experiences.)

"LGBT-ness" is not one thing. It is a political/cultural category that lumps together several demographic categories. I continue to think gay men, at least, are probably (mostly?) born that way.

The Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology did a detailed report on the LGBT increase. Quote:

"When we look at homosexual behavior, we find that it has grown much less rapidly than LGBT identification. Men and women under 30 who reported a sexual partner in the last five years dropped from around 96% exclusively heterosexual in the 1990s to 92% exclusively heterosexual in 2021. Whereas in 2008 attitudes and behavior were similar, by 2021 LGBT identification was running at twice the rate of LGBT sexual behavior.

[...] high-point estimate of an 11-point increase in LGBT identity between 2008 and 2021 among Americans under 30. Of that, around 4 points can be explained by an increase in same-sex behavior. The majority of the increase in LGBT identity can be traced to how those who only engage in heterosexual behavior describe themselves"

FWIW, I don't think it's a homophobic viewpoint, but it seems like a somewhat bitter perspective, of the sort generally associated with, but not implying, homophobia. Anyway, it's tangential to the main point.

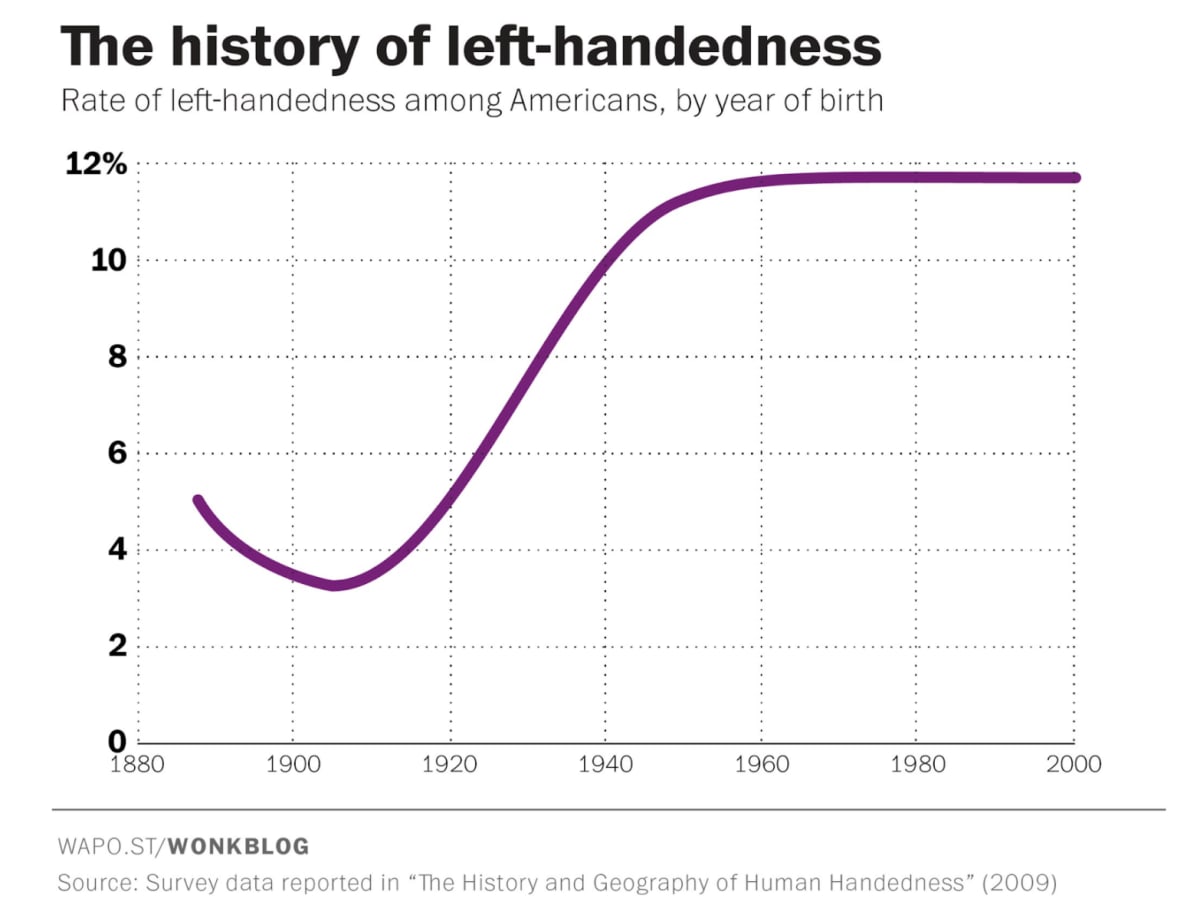

Re: social pressure: I was thinking of the "lefthandedness over time" graphs than got viral last year (of course the graphs could be false; the one fact-checker I found seems to think it's true):

The two obvious explanations are:

- Left-handed acceptance culture led to people living more childhood experiences that subtly influenced them in ways that made them turn out left-handed more often.

- People who got beat by their teacher when they wrote with their left hand learned to tough it out and use their right hand, and started to identify as right-handed. As teachers stopped beating kids, populations reverted to the baseline rate of left-handed people.

Occam's razor suggests the latter. People got strongly pressured into appearing right-handed, so they appeared right-handed.

If we accept the second explanation, then we accept that social pressure can account for about 8 points of people-identify-as-X-but-are-actually-Y. With that in mind, people going from 1.8% to 20% seems a bit surprising, but not completely outlandish.

Anyway, all of the above is still tangential to the main point. Even if we assume all of the difference is due to childhood imprinting, we still have rates of LGBT-ness going from 5.8% to 20.8% (depending on how you count). No matter where that change comes from, it's going to impact how much people have sex with opposite-sex people, and any study that doesn't account for that impact and reports a less-than-20% change in the rate-of-having-sex is, I believe, close to worthless.

Fewer friends, relationships on the decline, delayed adulthood, trust at an all-time low, and many diseases of despair. The prognosis is not great.

By Anton Stjepan Cebalo

One of the most discussed topics online recently has been friendships and loneliness. Ever since the infamous chart showing more people are not having sex than ever before first made the rounds, there’s been increased interest in the social state of things. Polling has demonstrated a marked decline in all spheres of social life, including close friends, intimate relationships, trust, labor participation, and community involvement. The trend looks to have worsened since the pandemic, although it will take some years before this is clearly established.

The decline comes alongside a documented rise in mental illness, diseases of despair, and poor health more generally. In August 2022, the CDC announced that U.S. life expectancy has fallen further and is now where it was in 1996. Contrast this to Western Europe, where it has largely rebounded to pre-pandemic numbers. Still, even before the pandemic, the years 2015-2017 saw the longest sustained decline in U.S. life expectancy since 1915-18. While my intended angle here is not health-related, general sociability is closely linked to health. The ongoing shift has been called the “friendship recession” or the “social recession.”

My intention here is not to present a list of miserable points, but to group them together in a meaningful context whose consequences are far-reaching. While most of what I will outline here focuses on the United States, many of these same trends are present elsewhere because its catalyst is primarily the internet itself. With no signs of abating, a new kind of sociability has only started to affect what people ask of the world through the prism of themselves.

The topic has directly or indirectly produced a whole genre of commentary from many different perspectives. Many of them touch on the fact that the internet is not being built with pro-social ends in mind. Increasingly monopolized across a few key entities, online life and its data have become the most sought-after commodity. The everyday person’s attention has thus become the scarcest resource to be extracted. Other perspectives, often on the left, also stress economic precarity and the decline of public spaces as causes. Some of these same criticisms have been adopted by the New Right, who also indict the culture at large for undermining traditions of sociality, be it gender norms or the family. Believing it disproportionately affects men, this position has produced many lifestylist spinoffs: Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOW), trad-life nostalgia, inceldom, masculinist groups, and hustle culture with a focus on 'beating the rat race.’ All of these subcultures are symptoms of the social recession in some way, for better or worse.

Often standing outside this conversation altogether are the self-described ‘adults in the room’ — professional media pundits, politicians, bureaucrats, and the like, disconnected from the problem themselves, but fixated on its potential to incubate political extremism. Entire institutes have been set up to study, monitor, and surveil the internet’s radicalizing tendencies buoyed by anti-social loneliness. The new buzzword often used in this sphere is “stochastic terrorism” and the need to contain some unknown, dangerous online element taking hold of the dispirited. The goal here is not to solve a pernicious problem, but instead to pacify its most flagrant outbursts.

We have no clear, comparative basis on which to judge what will emerge from the growing number of people who feel lost, lonely or invisible. The closest comparison comes from the early 20th century when, for the first time, millions of provincial people moved to major cities to pursue their dreams. Many uprooted themselves then only to be poor and unfulfilled, who were later easily excited into a mania over mass politics and culture. That’s why German novelist Herman Broch in his story The Sleepwalkers (1930) writes his panorama of WWI as rooted in “the loneliness of I” among three of his characters. Likewise, nobody cares for Gregor Samsa in Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (1915), who is compelled to go to work despite not even recognizing himself any longer. The alienated product of mass industrial society is familiarly described in W.H. Auden’s poem The Age of the Anxiety (1948) — “miserable wicked me / how interesting I am.”

While data and polling have their limits, they are a useful starting point for concretely discussing the social recession and whether it’s here to stay. I’ve collected some numbers on the shift happening across a few key areas: community, friendship, life milestones, relationships, and trust.

By the Numbers — Community & Social Activities

In 2000, Bowling Alone by political scientist Robert D. Putnam was published to much praise for its breadth of research. The book documents the decline of sociability in the United States since the 1950s. It mainly traces the dwindling number of Americans frequenting civic organizations such as religious services, volunteer work, sports clubs, hobbyist groups, and so on.

The book was one of the first to quantitatively determine that, yes, the traditional American community was on the decline. It remains a staple within political science courses today. Yet, many of the metrics used in the study are today a bit dated. Even the title does not evoke the relevance it once did (not even bowling has been spared the decline of social activities). Moreover, in the year 2000, it was far easier to see the trend as ‘fixable’ because it was not overwhelmingly determined by any one factor.

Putnam’s work is an assessment of social life of a different kind, before the internet's mass adoption. That world is clearly never coming back. If we take one metric commonly cited in the book, church membership, the decline Putnam describes is exceptionally mild compared to what came after.

U.S. Church Membership Falls Below Majority for First Time (Gallup, 2021)

Rather than go through them one by one, Putnam’s trends can be assessed more contemporaneously through a simple metric: screen time, a proxy for time spent not doing community activities in person. Rather than bowling alone, Americans are instead browsing alone over 7 hours daily on average and increasing every year. As of 2021, some 31% of Americans claim to be online “almost constantly.” The world Putnam is describing arguably does not register with the same relevancy it once had.

Friendships

If we are browsing alone rather than bowling alone, the real metric to look at is friendships themselves. The past few decades have recorded a steep decline in people’s circle of friends and a growing number of people who don’t have any friends whatsoever. The number of Americans who claim to have “no close friends at all” across all age groups now stands at around 12% as per the Survey Center on American Life.

It’s been known that friendlessness is more common for men, but it is nonetheless affecting everyone. The general change since 1990 is illustrated below.

Taken from "Adrift: America in 100 Charts" (2022), pg. 223. As a detail, note the drastic drop of people with 10+ friends, now a small minority.

The State of American Friendship: Change, Challenges, and Loss (2021), pg. 7

Although these studies are more general estimates of the entire population, it looks worse when we focus exclusively on generations that are more digitally native. When polling exclusively American millennials, a pre-pandemic 2019 YouGov poll found 22%have “zero friends” and 30% had “no best friends.” For those born between 1997 to 2012 (Generation Z), there has been no widespread, credible study done yet on this question — but if you’re adjacent to internet spaces, you already intuitively grasp that these same online catalysts are deepening for the next generation.

Life Milestones & Relationships

There have been many psychological profiles of “late adulthood,” common among those born from the 1990s onward. Many of the milestones — getting a driver’s license, moving out, dating, starting work, and so on — have been delayed for many young adults.

The trend became obvious starting in the 2010s. In 2019, it was compiled in a comprehensive study titled The Decline in Adult Activities Among U.S. Adolescents, 1976-2016.

Illustrated by Axios (2017).

The same paper looked at how often high schoolers went out without their parents, showing a similar decline.

The Decline in Adult Activities Among U.S. Adolescents, 1976-2016 (2019)

Much of this is not necessarily “bad”, and it’s more symptomatic than anything else. It’s something of a mixed bag. For example, delayed adulthood is linked to less of a desire to engage in risky behavior like delinquency or excess drinking. While risk avoidance may be preferable, it also tracks along a decline in sociability. It is therefore bundled with other personal costs: mental health among people native to the internet continues to worsen amid an increase in so-called ‘diseases of despair’ in the United States more generally. These were the leading causes of the drop in life expectancy before the pandemic.

Finally, there is the most-discussed stat of them all — the rapid increase of people who have had no sexual relations since they turned 18, amid a time of unprecedented sex positivity no less. Writer Katherine Dee, who writes on the substack Default Friend, has flipped this common understanding and said that the coming wave is one of disembodied ‘sexual negativity’ rather than free love (just FYI, her article is paywalled).

Compiled by /u/TheGoldenChampion

The results, though, are not unexpected. A disembodied, online life produces less physical intimacy despite mass culture presenting us with an image that says otherwise. The stat went viral precisely because it showed what many were suspecting and could now concretely confirm.

Trust

One last aspect missing from all this is trust. Trust is the building block of all sociability. The past 50 years have been nothing short of America’s transformation from a high-trust to a low-trust society, a collapse of authority across all levels: social, political, and institutional.

In 2022, trust dropped to a new average low—a development that has been the trend since the 1970s.

Confidence in U.S. Institutions Down; Average at New Low (Gallup, 2022)

The decline of trust in the United States across the board is a standalone topic all on its own, already the subject of many books and investigations. I mention it here because trust is the social glue of any society. Regimes crumble and collapse due to a lack of belief in themselves. A lack of trust in institutions makes for a lack of trust in other people as well.

Protection, Progress, and Perseverance (2020), pg. 24

Americans' Trust in Themselves (2021). Although higher than the Pew Research findings, the poll was more general rather than being on the public’s “political wisdom.”

Most Americans do perceive that trust has diminished among the general population. The vast majority are “worried about the declining level of trust in each other.” Many also feel that they no longer recognize their own country (although this is likely caught up somewhat in political partisanship).

The state of personal trust (Pew Research Center, 2019).

The erosion of trust in the U.S. began decades ago after Watergate and the proceeding “Crisis of Confidence” during the 1970s. Still, it binds our current time to a more familiar past cynicism. Skepticism toward the state has evolved into more generalized distrust toward society at large, amplified by the internet.

The New Individual

The data presented is enough to sketch out an archetype of the new individual, a growing minority: one who is plugged in, dispirited and often feels invisible. Carl Jung wrote that personal meaning comes “when people feel they are living the symbolic life, that they are actors in the divine drama.” In such a frayed sociality, the drama that would give one meaning closes. What often enters instead is nostalgia, exaggerated hatred, and the desire to be saved.

Right now, the dispirited are only beginning to agitate the political center which is led by mostly an older generation socialized in a different way. The current U.S. government has been called the “oldest government in history.” It fits the proper definition of a gerontocracy or ‘rule of the old.’ As of 2022, over 23% of Congress is over 70 years old, and the median age is 61.5. American political power has so far only sporadically felt the effects of the new individual at the ballot box, while at the same time chastising the public for it. The politics of the social recession has therefore only really just started. Analyst Martin Gurri touches on this in his book The Revolt of The Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium (2013). As he argues, the digital public lacks a coherent program and is motivated by negation, and the tearing down of idols and authority. We cannot expect the new individual to simply be contained to just his or her own alienation, pacified and alone. That alienation will inform beliefs on how society itself should be organized and will be the substance of some future worldview, whatever it may be.

As a starting point for remedies, it should be admitted that this process cannot be reverted nor can we expect political management from above to contain these asocial sentiments. The healthier alternative involves rethinking internet infrastructure on pro-social ends: platforms owned by the people using them with community prerogatives in mind. I’m not going to pretend to know what that will look like since much of it has to happen organically. While the trends described here may be a “new normal” in the sense that they cannot be reversed, I still think another healthier kind of online community is imaginable. The internet does not need to be joined at the hip to a permanent social recession like it is now.

If you found this post worth your time, consider subscribing to my newsletter Novum. It's a hobbyist project of mine and free.