I'm not sure that I buy that critics lack motivation. At least in the space of AI, there will be (and already are) people with immense financial incentive to ensure that x-risk concerns don't become very politically powerful.

Of course, it might be that the best move for these critics won't be to write careful and well reasoned arguments for whatever reason (e.g. this would draw more attention to x-risk so ignoring it is better from their perspective).

(I think critics in the space of GHW might lack motivation, but at least in AI and maybe animal welfare I would guess that "lack of motive" isn't a good description of what is going on.)

Edit: this is mentioned in the post, but I'm a bit surprised because this isn't emphasized more.

[Cross-posted from EAF]

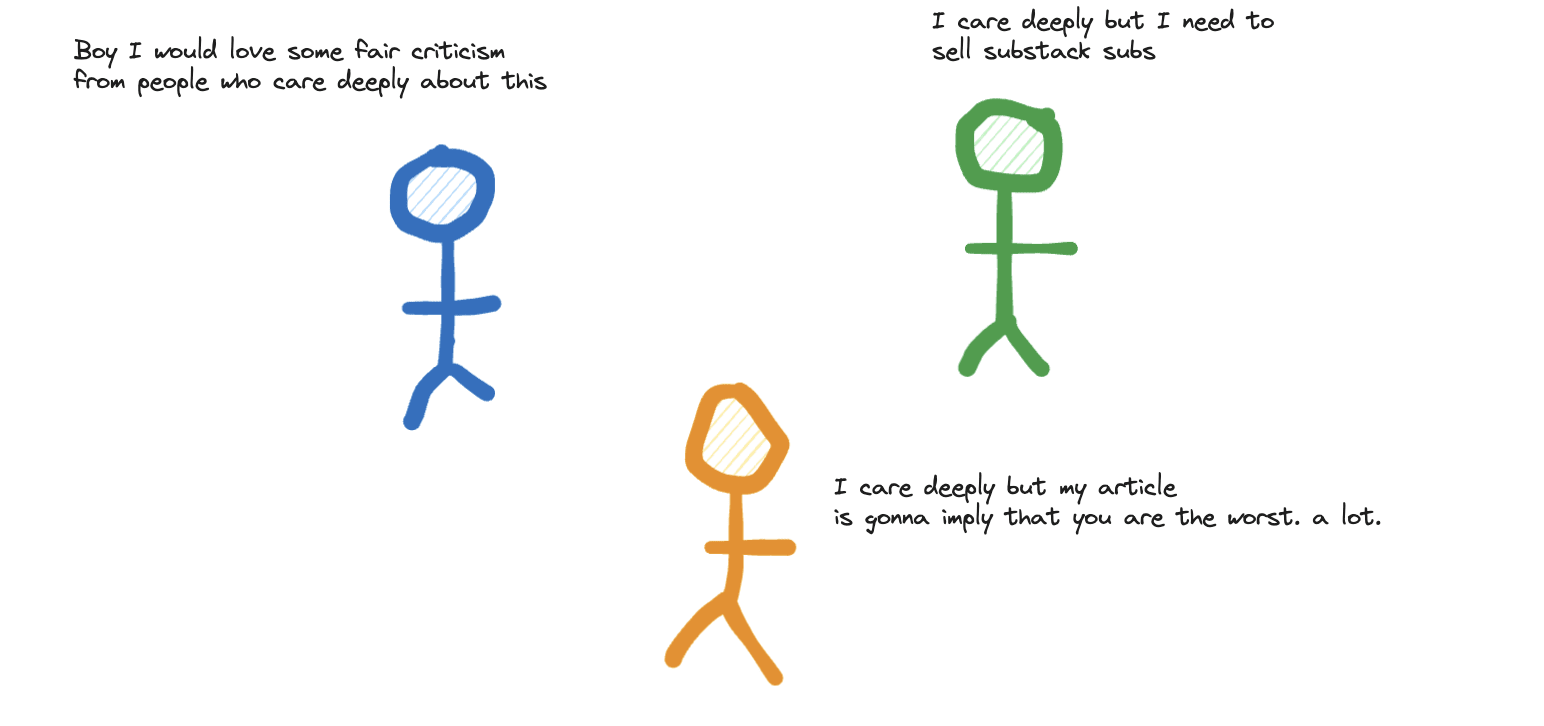

Feels like there is something off about the following graph. Many people writing critiques care a lot. Émile spends a lot of time on their work for instance. I don't think motivation really catches what's going on.

Epistemic status: generating theories

I theorise it's two different effects in one:

- The voices we hear in the discussion (which links to yours)

- The norms of the communities holding those voices

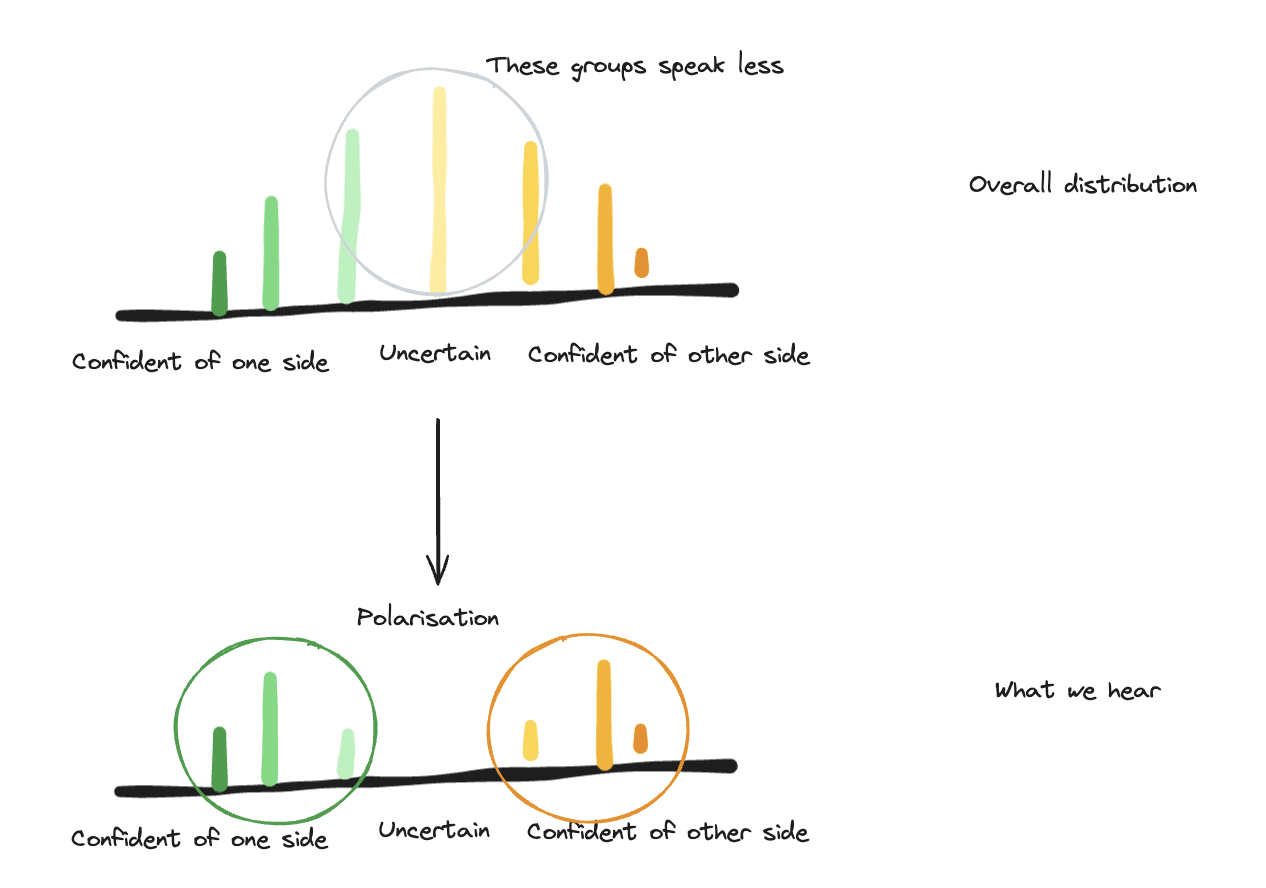

First, as you say, the voices we hear most are the most confident/motivated, which leaves out a lot of voices, many of whom might talk in a way we'd prefer. Instead we only hear from the fringes, which makes a normal distribution look bimodal.

I wonder if this is more like supply and demand than your "bars" model. Ie it's not about crossing a bar but about supplying criticism that people demand. And correcting a status market - EA is too high status, let's fix it.

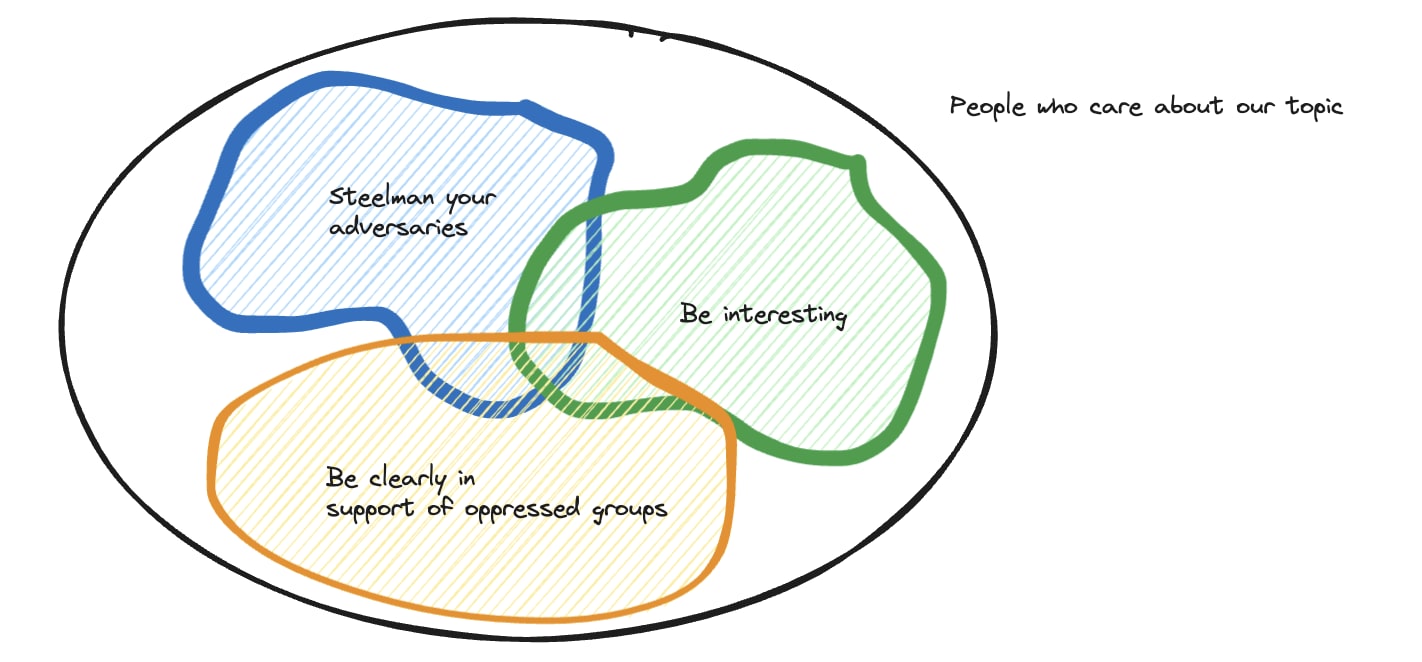

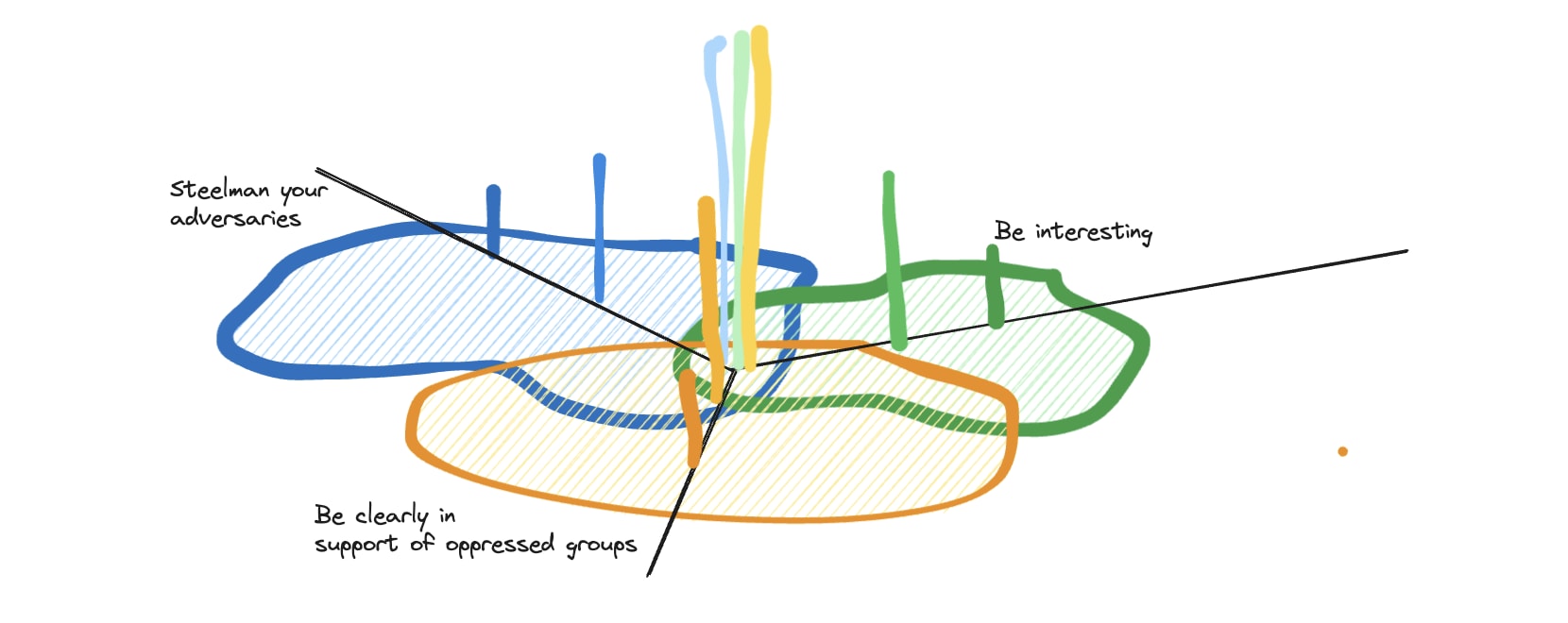

Secondly, the edges of this normal distribution have different norms. Let's say there are 3 areas:

- one likes steelmanning in disagreements

- one likes making clear to be on the side of minorities

- one likes being interesting

Let's imagine we are discussing something that has people from all these areas.

The people who like each of these things most strongly perhaps talk more, as in the above example. But not only do they talk more, they talk differently. So now the discussion is polarised in different languages, because the people in the middle are less confident and speak less (this jump feels like weakest step in the argument[1])

Amount of people with different views (central line is one group of people, who hold all views weakly)

So now we have this:

So I think probably my overall thing about why criticism is poor is something like "criticism looks poor to us because it isn't for us". It is for the people in the same communities by whom it is written. And probably to them our pieces look pretty poor as it is.

Some questions then:

- How do we respond in language that other groups will understand?

- Should we want to? Torres for instance seems to be a bit of a bully. But I'm not sure that makes their arguments bad. But if I were doing it they would definitely call me out for it.

- Is it worth taking time to really try and write the strongest versions of criticism in language we understand. Or find ways for people to signal confusion

- ^

Why should the people in each group talk most confidently? I dunno, but I hear a lot more from Yud, Alman, Adreeson and Torres than many more moderate voices. Feels like something is going on here. Can anyone suggest it?

Typos:

"Al gore"->"Al Gore"

"newpaper"->"newspaper"

"south park"->"South Park"

"scott alexander"->"Scott Alexander"

"a littler deeper"->"a little deeper"

"Ai"->"AI"

(. . . I'm now really curious as to why you keep decapitalizing names and proper nouns.)

Regarding the actual content of the post: appreciated, approved, and strong-upvoted. Thank you.

Good article.

It's an asymmetry worth pointing out.

It seems related to some concept of "low interest rate phenomenon in ideas". Sometimes in a low interest rate environment, people fund all sorts of stuff, because they want any return and credit is cheap. Later much of this looks bunk. Likewise, much EA behaviour around the plentiful money and status of the FTX era looks profligate by todays standards. In the same way I wonder what ideas are held up by some vague consensus rather than being good ideas.

This feels like Scott Alexander could've written something about, and it has the same revelatory quality.

Disclaimer: While I criticize several EA critics in this article, I am myself on the EA-skeptical side of things (especially on AI risk).

Introduction

I am a proud critic of effective altruism, and in particular a critic of AI existential risk, but I have to admit that a lot of the critcism of EA is hostile, or lazy, and is extremely unlikely to convince a believer.

Take this recent Leif Weinar time article as an example. I liked a few of the object level critiques, but many of the points were twisted, and the overall point was hopelessly muddled (are they trying to say that voluntourism is the solution here?). As people have noted, the piece was needlessly hostile to EA (and incredibly hostile to Will Macaskill in particular). And he’s far from the only prominent hater. Emille Torres views EA as a threat to humanity. Timnit Gebru sees the whole AI safety field as racist nutjobs. In response, @JWS asked the question: why do EA critics hate EA so much? Are all EA haters just irrational culture warriors?

There are a few answers to this. Good writing is hard regardless of the subject matter. More inflammatory rhetoric gets more clicks, shares and discussion. EA figures have been involved in bad things (like SBF’s fraud), so nasty words in response are only to be expected.

I think there’s a more interesting explanation though, and it has to do with motivations. I think the average EA-critical person doesn’t hate EA, although they might dislike it. But it takes a lot of time and effort to write an article and have it published in TIME magazine. If Leif Weinar didn’t hate EA, he wouldn’t have bothered to write the article.

In this article, I’m going to explore the concept of motivation gaps, mainly using the example of AI x-risk, because the gaps are particularly stark there. I’m going to argue that for certain causes, the critiques being hostile or lazy is the natural state of affairs, whether or not the issue is actually correct, and that you can’t use the unadjusted quality of each sides critiques to judge an issues correctness.

No door to door atheists

Disclaimer: These next sections contains an analogy between logical reasoning about religious beliefs and logical reasoning about existential risk. It is not an attempt to smear EA as a religion, nor is it an attack on religion.

Imagine a man, we’ll call him Dave, who, for whatever reason, has never once thought about the question of whether God exists. One day he gets a knock on his door, and encounters two polite, well dressed and friendly gentlemen who say they are spreading the word about the existence of God and the Christian religion. They tell them that a singular God exists, and that his instructions for how to live life are contained within the Holy Bible. They have glossy brochures, well-prepared arguments and evidence, and represent a large organisation with a significant following and social backing by many respected members of society. He looks their website and finds that, wow, a huge number of people believe this, there is a huge field called theology explaining why God exists, and some of the smartest people in history have believed it as well.

Dave is impressed, but resolves to be skeptical. He takes their information and informs them that he while he finds them convincing, he wants to hear the other side of the story as well. He tells them that he’ll wait for the atheist door-to-door knockers to come and make their case, so he can decide for himself.

Dave waits for many months, but to his frustration, no atheists turn up. Another point for the Christians. He doesn’t give up though, and looks online, and finds the largest atheist forum he can find, r/atheism.

Dave is shocked at crude and nasty the atheists he encounters there are. He finds the average poster to be a socially inept and cringe, mainly posting bad memes and complaining about their parents. Dave does not find statements like “f*ck your imaginary sky daddy” to be a convincing rebuttal to thousands of years of theological debate. There are only occasionally actual arguments for atheism, which are not very well argued. He takes the arguments to the door to door preachers, and they have a prepared rebuttal of every single one, using articles by a highly educated, eloquent and polite priests and religious thinkers.

From this whole experience, Dave concludes that God is probably real, and that atheists haven’t really studied things properly or are blinded by bias against their parents or bad apples in the religious community.

What went wrong here?

I am making no factual claims about the existence of God in this post. I am personally an atheist, but I respect and admire many religious people, and I do not think believing in god is a foolish belief.

But what I will say is that I think Dave’s reasoning for concluding that God is real is flawed. And I think the main flaw lies in failing to account for motivation gaps.

If you believe in God (let’s say, the Christian evangelical version), that belief comes with duties and obligations. People who don’t believe in god are missing a personal connection to the greatest being in the universe, and in some versions may be condemned to be tortured for all eternity. If you believe this, it’s not hard to find a moral obligation to convert as many people as possible. The religion you subscribe to will have a bunch of rules and laws you need to follow, which comes with a need to understand and join together with like minded people at church, and donate money so they can print lots of fancy pamphlets and hire priests and religious scholars to guide people and argue for God’s existence. The church also coordinates volunteers to go door to knocking so people can be converted. All of these actions are fairly logical implications believing in a particular version of the Christian God.

If you don’t believe in God… you don’t believe in God, and don’t really have to think about it very much. If the religious people start putting in, say, restrictive anti-abortion policies, you might be pissed off and organise against those. But you’ll find plenty of Christians who are also pro-choice, and you may find it counterproductive to argue about God’s existence. Since you believe that Atheism is correct, you might think it’s good to argue for it because you like spreading truth. But if you don’t think the stakes are high, would you really put that much effort into it? The reason there are no atheist door knockers is that doorknocking is a massive pain in the arse, and no atheists are motivated enough to actually do it. Usually every atheist will know of another cause that they think is more pressing than spreading atheism.

The majority of my friends are atheist, but none of them would be caught dead posting on r/atheism or making it a large part of their identity. Actively trying to deconvert people is seen as rude and gauche, with the attitude that if they’re not harming anyone, you’re just being a dick.

Who does end up advocating against religion itself? Bitter ex-religious people, people like Richard Dawkins who see religion as one of the biggest problems in the world, and a few comedians like Ricky Gervais who find the whole thing absurd. You might also see it be absorbed as a smaller part of greater movements that do come with motivations, like communism in China. As an atheist myself, I find most of these people annoying and I don’t like them.

So the imbalance that Dave sees, where the Christians are glossy, high-effort and highly organised and the Atheists are a bunch of weirdos on internet forums with bad memes, actually tells you very little about how correct the position is. It’s simply the natural consequence of motivation gaps arising from their beliefs. And the reason he finds atheists so needlessly angry and hostile is not that atheists are all hostile and angry: it’s that the non-angry atheists don’t bother to advocate hard for their beliefs.

Fortunately, in this case, the question of God’s existence and nature has been discussed for literal millenia, so if he actually did dig deeper he could find the philosophical literature on the subject, and be exposed to actual serious, high-effort arguments on both sides of the aisle.

I think that this is a case where the less motivated side is correct, but there are other cases where I believe the more motivated side is correct. The people who thought CFC’s were tearing apart the ozone layer were more motivated than the people who thought it was no big deal, but they were also correct, and they were proven to be correct.

Motivation gaps in AI x-risk

Emily is a young, highly intelligent high school graduate who is considering what to do with her life. While googling careers, she comes across an ad from 80,000 hours discussing career options, and finds an article arguing that there there could be an existential risk from Artificial Intelligence. Disturbed, she researches more on the subject, and encounters even more convincing articles from highly intelligent full time employed “AI safety” researchers, slick youtube videos, podcasts, etc. She goes to a local meetup group, where dozens of smart, motivated people are convinced of the dangers of AI, have strong arguments in favour, and are committed to acting against them.

However, Emily wants to maintain a skeptical instinct. She resolves to try and look at the opposing side as well. Of course, no “Ai x-risk is bunk” ads show up on her instagram feed. But even when she googles “Ai existential risk debunk ”, the results are pretty damn weak. Like, the top result has no actual arguments against AI risk, it just states “this is bunk” and starts talking about near-term harms.

She sees a few articles from Emille Torres, but they seem needlessly fearmongering and hostile, and she’s sent an article pointing out their dishonest behaviour. Timnit Gebru is more straightforward, and has some interesting academic articles, but her online presence is more interested in culture war discourse and insults than object level arguments against AI risk.

She finds r/sneerclub on reddit, which seems like the biggest online forum criticizing EA, but it leaves a bad taste in her mouth. She finds the arguments are generally low-effort when they occur, the critiques are often inaccurate or lack reading comprehension, the mods are obnoxious and ban-happy, and many commenters are just making mean-spirited jabs at political enemies.

When she brings up the best arguments she found to the EA people, they all have ready made rebuttals, written by very smart, highly eloquent and educated professionals employed at EA orgs.

From this experience, she concludes that the risk of AI doom is high, and that the critics of AI doom are misguided people blinded by their culture war biases. She pursues a career in AI policy.

EA gap analysis

I argue here that Emily and Dave are making the exact same mistake. Emily is not accounting for the motivation gaps involved in the AI doom question.

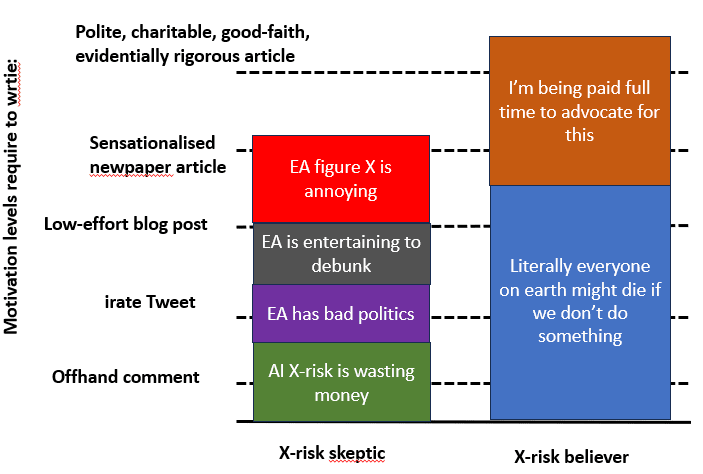

If you think that P(AI doom) is high (or even medium) then the stakes are unbelievably high. Humanity is staring down the barrel of a gun, and the lives of literally everyone on the planet are in danger. If you believe in that, then obviously it comes with at least some obligation to try and prevent it from happening, which involves spreading the word about the threat. And to spread the word, you want a big organisation of people, you need to present your arguments in a flashy way that can win over the masses, you want to prepare rebuttals to the most common objections, and so on and so forth. The AI safety ecosystem is being funded to the tune of half a billion dollars, with dozens of organisations employing hundreds of full-time employees, a decent fraction of which are working on advocacy.

This is all a completely reasonable response to believing in a high risk of human extinction!

If you think that P(AI doom) is low.. then you think that P(AI doom) is low. It comes with no inherent moral obligations. You might be annoyed that people are spreading bad ideas around, but it’s not the end of the world. Meanwhile, there is climate change, pandemic risks, global poverty, all of which you would probably view as more pressing that people being wrong about AI.

You might be motivated to push back if the false ideas of the AI x-riskers start affecting you, like the 6 month AI pause idea. But you only need to push back on the policy, not the idea itself. If you are concerned about the short-term, non-doom effects of AI developments, you would probably rather spend your time raising concerns about those rather than debunking x-risk fears. You might say that x-risk is a “distraction from near term worries”, which is probably not actually true in terms of media coverage, but is true in regards to the use of your personal time and energy. There are ~0 organisations dedicated to AI x-risk skepticism, and I’m having trouble thinking of more than a tiny handful of people who relies on AI skepticism as a major source of income. Compared to the half billion in funding for AI safetyism, AI skepticism funding looks downright nonexistent.

So who is motivated to dedicate significant time to attacking AI x-risk beliefs, generally in their spare time? This I will explore in more depth in the next section, but it’s mostly people motivated by fear, hatred, annoyance, tribalism, or a desire to mock, or some combination of all of these.

The same principle applies to EA in general, proportional to how effective you think EA is. Even if you only believe in malaria nets, people donating to ineffective charities are still, in effect, letting actual, real people die that otherwise would have been saved. Whereas someone who (wrongly) thinks malaria nets are ineffective will, by default, not bother engaging.

I would guess that most of the people who have heard EA or AI x-risk arguments, but don’t agree with them, feel no large motivation to oppose them. They read an article or two, find it unconvincing, and move on with their lives.

If you are the average person, there is no motivation to get familiar with EA jargon, spend hours and hours engaging with the current debates, learn about all the wide ranging topics that go into estimating complex problems like P(doom), and then spend dozens of hours preparing high quality critique of the movement. All for the purpose of, what, posting an article on the EA forum that will most likely be lightly upvoted but largely ignored?

I’m a person that has done all of the above, and I don’t think it was a rational decision on my part. Don’t get me wrong, the EA community is in general quite lovely, I’ve gotten lots of praise and encouragement, and I’m proud of what I’ve written. But it’s taken up a large amount of time and effort that could have been spent on other things, and at times it’s been quite unpleasant and harmful to my mental health. Why would someone do such a thing?

Counter-motivations

I think there a few factors that close motivation gaps, and result in high effort stuff on the non-intrinsically motivated side. My main example would be the issue of climate change. Naively this theory would predict that the climate change believers would be highly motivated, whereas the deniers would treat the matter with a shrug. In reality climate denialism is high effort, popular and well funded, despite being objectively false.

In this section I will explain a few counter-motivations that can bring someone to put energy into a critique. The problem is that almost all of them come with corresponding flaws as a result of what motivated you in the first place.

Moral backlash:

Defeating climate change is a massive, world changing task, that requires sweeping societal changes to prevent catastrophe. And whenever you try to change anything, some of the people affected will try and push back. You put in a carbon tax, people will see their bills go up and start fighting you. You put up a wind turbine, people will complain about blocking the view (or incorrectly think it is making them sick). This all provides motivation for climate denial: fear and moral objection to the actions of the activists.

Up until recently, there hasn’t been much of this motivation in opposing EA or AI x-risk. I mean, a few years ago EA was just funneling rich peoples money into malaria nets, which is hard to get super worked up about. But with the rise of longtermism, the SBF debacle, and the move towards policy intervention, I think this is changing.

I think this motivation underlies the Emille Torres and Timnit Gebru section of EA haters. These people think the EA movement is actively harmful and dangerous. Torres isn’t even super skeptical of AI x-risk, they just think that the dreams of utopian singularities within EA will make everything worse. Whereas Gebru sees EA as a bunch of white tech bros using fake AI hype as an excuse to not fix real world harms like discrimination (although I don’t fully agree, I do sympathise with this point of view).

Conversely, we have the e/accs (effective accelerationists), who are often super mad that AI doomers might stall or prevent a technological singularitian utopia. Think of all the people that will die because the nigh-omnipotent AI god won’t appear! Hence Andreessons (highly unconvincing to me) techno-utopian manifesto.

When people motivated by moral backlash write critiques, they will probably come off as hostile, because they think EA does bad things that inspire fear or hatred. These feelings are sometimes entirely justified. SBF committed a bunch of fraud and very much did harm a lot of people!

Politicisation/tribalism:

The realm of politics is one where motivation is easy to find. If you are a committed democrat, the republicans must be opposed at all costs for the preservation of your values. And of course, the opposite applies as well. So if an issue starts being primarily associated with one side of the political aisle, the other side will be tempted to oppose it. This is not necessarily irrational behaviour: different political parties can have hugely different effects on the world and peoples lives.

The existence of climate change was initially not treated as a partisan issue, but over time became associated with the political left. This gave the right an incentive, either genuinely or cynically, to try and convince people it didn’t exist, so climate change denial got hooked up to all the existing right wing infrastructure, like fox news panels, conservative newspapers, right wing websites, and so on. By being sucked into the larger ongoing political war, the motivation gap was lifted.

The flaw here is, of course, that arguments can treated as weapons in a war for power, so critiques motivated by politics are highly incentivised to hide arguments that are good for the enemy and distort arguments in your favour, so that your side wins.

EA has deliberately aimed to try and escape partisanship and culture wars. It is impossible to completely succeed in this, and many attacks on EA are motivated by political disagreements from both sides of the aisle. These attacks will obviously be somewhat hostile, because they are attacking a political enemy, not trying to persuade them.

Monetary incentives for skepticism:

One of the key arguments for academic tenure is that it ensure an academics pay is completely detached from the positions they advocate. A professor of climatogy can decide that climate change is false and try to argue that case, and they will still get paid a professors salary.

Of course, this does not extend to, say, grant applications and other sources of money, or to early career researchers. Fortunately for the climate change denialists (and unfortunately for us), there is another source of ample funding: Fossil fuel companies and their allies, for which climate change initiatives are an active threat to billions of dollars of revenue. This is ample motivation to toss some money to some convincing sounding denialists, and to try and make the climate denial case as strong as possible.

Surely the same reasoning applies to AI skepticism? Well I would argue not yet, but that may soon be changing. Up until now, AI x-risk fears have not been an obstacle to the profits of tech companies. Sort of the opposite: EA and x-riskers have played a role in starting openAI and triggering AI arms races. Even some AI regulations aren’t necessarily bad for big AI companies, as they could kneecap small market players that can’t afford to keep up with them. However, if the movement starts getting regulations with teeth through, we might start seeing big company funding go to AI x-risk debunkers, with a bias towards accelerationists.

Of course if such funding did happen, it would then be biased towards the views of the people funding them, much like climate denialist orgs.

What about EA funding? Well, ultimately, they come from donations. This ties straight back to the initial motivation gap: If you are concerned about AI, you might be willing to donate to AI x-risk advocacy groups. If you are not concerned about AI, would you care enough to donate to an “AI x-risk is bunk” advocacy group?

EA has some legitimate attempts to fix this, with cause neutral funding and competitions. The global priorities institute in particular seems to publish a lot of papers that criticise EA orthodoxy. Prizes like the AI worldview challenge are nice encouragement for people who are already somewhat motivated to criticize things, but they pale in comparison to the reliable pay of a full time x-risk advocate. You’re just not guaranteed to win: I have not made a single cent off my numerous skeptical articles on the subject.

Articles motivated by money are probably more likely to be calm in tone, but there’s always a conflict of interest in that the writer is incentivised to agree with their funder.

Annoyance/dislike:

Some people find Al gore smug and pretentiousness. Therefore, when they see Al Gore preaching about this new “global warming” thing that they don’t really buy, they get motivated to attack it to take the smug guy down a peg. Hence the south park episodes mocking climate change by targeting Al Gore specifically.

Similarly, someone who dislikes certain EA figures might be annoyed at how prominent and influential they are getting, and be motivated to knock them down in response. I must confess this is part of my motivation.

For example, my impression is that Leif Weinar really, really, dislikes Will Macaskill for some reason, and this was a key reason he wrote his time article. Articles like these motivated by dislike are usually hostile in tone unless the writer takes great effort to hide it.

Entertainment value

There are people who are simply in it for the entertainment value. People being wrong, in a weird way, can be very interesting or funny. Or you can enjoy the intellectual challenge of debunking incorrect opinions.

Why did 3.6 million people watch this hour long video dunking on flat earthers? Because the topic of people believing crazy things is fun and interesting.

This is a main motivator behind my work, honestly. I could dedicate more time to debunking hardcore Trumpists or whatever, but that would feel like a major chore. Whereas debunking something like “a super-AI can derive general relativity from a blade of grass” is just way more fun and interesting.

This is something of the point of circlejerky subreddits. The people on r/atheism generally aren't actively trying to deconvert or debate with their posts. They just want a safe space to hang out with people who already agree with them about the supposed wrongness/harm of religion.

The problem with this type of criticism is that for the most part it’s usually pretty lazy. If you just want to make people laugh, there’s no need to be charitable or high-effort. The average r/sneerclub post consisted of finding something seemingly absurd or offensive said by a rationalist and then mocking it. The resulting threads are obviously biased and not epistemically rigorous. Like, Wytham abbey was technically a manor house, but “EA gets a castle” is objectively a funnier meme. There are sometimes good arguments in there (I think my old sneerclub posts weren’t terrible), but they’re not the point of the community, and you shouldn’t expect them to be common.

Truth-seeking:

The feeling that someone is wrong on the internet can be a powerful motivation in the right conditions. And, in a way, this is one of the key drivers of the scientific method. People strive for truth for truth’s sake, but also because people being wrong is annoying. Climate science might look like a bunch of people in lockstep, but if you dig a littler deeper, you’ll see scientist X ranting that scientists Y’s climate model is obviously flawed because it neglected factors G, F and Q, how does that clown keep getting more citations than me!

However, I don’t think this alone is likely to motivate someone to offer up high-quality outsider critique. The internet has a limitless supply of incorrect statements, wrong beliefs, and misinformation. Why should a person focus on your issue in particular, rather than

I do think EA does a good job internally encouraging this type of debate, and a general focus on truthseeking. In the next section I’ll outline why you can’t just rely on insider criticism.

You can’t rely on ingroup criticism

I think it’s a common opinion in EA that ingroup criticism is way better than outgroup criticism. It’s certainly more polite! Since EA is theoretically cause-neutral and truth-seeking, EA insiders theoretically have that “neutral” motivation to critique their beliefs. From this, it’s tempting to just ignore all outgroup criticism.

However, I think that relying too hard on ingroup criticism leads to pitfalls. There are reasons we prefer ingroup criticism that might be inflating their value beyond what is needed.

First: in-group criticism speaks our language, so we understand it easily. The EA movement has been marinated in the tone and jargon of the Rationalist movement, so we understand people that reference their “epistemic status” or whatever. But this is not a requirement for having insightful and correct opinions on something like, say, nanotechnology. So someone steeped in a different jargon language might come off as harder to understand and less persuasive, even if their views are correct.

Following on from this, we believe our opinions are correct. So the more someone agrees with us, the more we tend to trust their opinion. If someone believes everything you believe except for one issue, you will be more likely to listen to their reasoning on the very last disagreement and be persuaded. This is not a big deal if you already are mostly at the truth, but if you have a lot of things off, you risk being trapped in an epistemic dead end, where you only listen to people who are wrong in similar ways to you.

We are talking about speculative issues here. Poor assumptions and groupthink might affect the assumptions going into a climate model, but it can’t make the reading of a thermometer go up. There’s no equivalent for the behaviour of hypothetical super-intelligent AI’s: we can only make extrapolations from current evidence, and different people extrapolate in different ways. So it’s hard to escape from an epistemic dead end if one does occur.

There is also the risk of evaporative cooling of group beliefs (and a similar risk for selection bias in who enters). As AI risk becomes a bigger and bigger part of the EA movement, in-group criticism may become less and less useful, as non AI-riskers get more and more alienated from the movement. This will happen even if you’re super duper nice to them and are welcoming as possible. Sure, someone concerned about global health will be satisfied that like half of the EA funding still goes to global health, but if they jump ship to a global health agency, that number will be 100%. And an earn to giver doesn’t have to engage with the “EA movement” at all: they can just read the latest Givewell report and cut a cheque.

Lastly, EA is a big part of peoples lives. A significant number of people in EA, including a lot of the most influential people, rely on EA as their employer. Plenty of people also have EA as part of their identity, including their friends, partners, and family. EA is a source of identity and social status. These all introduce conflicts of interests when it comes to discussing the value of EA. Theoretically, you might be committed to the truth, but it’s not hard to see why people might be unconsciously biased against a position like “my heroes are foolish and all my friends should be fired”.

How to respond to motivation gaps

Note that some of these recommendations would benefit me and “my tribe” personally. Feel free to take that into account when evaluating them.

The dumb response to this concept would be to assume that because motivation gaps existed, that the less inherently motivated side must be correct. I hope I’ve given enough counterexamples to show that this is not true.

I think there is also a danger of proving too much with this concept. There are plenty of aspects of AI x-risk that are not explained by motivation gaps. It doesn’t explain why EA settled on AI risk in particular, as opposed to other forms of x-risk. It’s only a partial explanation for why AI fears are common among AI researchers. And obviously, it says nothing about the object level arguments and evidence, which are what ultimately matters.

I’m also not saying that because negative attitudes are more boosted and visible, that working on PR and avoiding scandals is pointless. If EA went out shooting puppies for no reason, it would rightfully get more criticism and hatred than it does now!

One way to react to this would be to try and compensate for motivation gaps when evaluating the strengths of different arguments. Like, if you are evaluating a claim, and side A has a hundred full time advocates but side B doesn’t, don’t just weigh up current arguments, weigh up how strong side B’s position would be if they also had a hundred full time advocates. A tough mental exercise!

Another reaction could be to set different standards for advocates and critics. You could choose to be more charitable and forgiving of hostility, in EA critics than you are in EA supporters, because otherwise you wouldn’t get any criticism at all. Or pick through a hostile piece and just extract the object level arguments and engage with those. (I think people did engage with most of the arguments in the Weinar article, for example).

If you wanted to be proactive, you could seek out an unfiltered segment on the community. For example, the forecasting research institute sought out superforecasters, regardless of their AI opinions, and paid them to do a deep dive into issue of AI x-risk and to discuss the issue with AI concerned people. This group gave a much lower estimate of x-risk than the EA insiders did. This gives us a better feeling for the average intellectual opinion, rather than the people filtered by motivations.

I want to be clear that I am advocating for somewhat unfair treatment, in that if you see an equally good article from a pro-AI risk perspective and and an anti-AI risk perspective, you should preferentially boost the latter, because of it’s rarity and in order to compensate for all the other disadvantages of that minority perspective.

The main thing I would emphasize is then when you do see the rare critique that is good, that is well argued and in good faith, don’t let it languish in obscurity. Otherwise, why would anyone bother to offer it up? For examples, in the last year of EA forum “curated posts” I couldn’t find any posts from AI skeptics (unless you count this?).

Leif Weinars bad article prompted mass discussion, multiple followup posts, and a direct response from EA celebrities like scott alexander. At the exact same time, David thorstadt has been writing up his peer reviewed academic paper “against the singularity hypothesis”, arguing against a widespread and loadbearing EA belief with rigorous argumentation and good faith. And the response has been… modest upvotes and a few comments. Where are the followup post responses? Where is the EA celebrity response? I would bet only a fraction of the people engaging with the time article have seen Thorstadts arguments. Ironically, if you want your ideas to be seen within EA circles, being flashy and hostile seems like the better strategy. Why bother writing a polite good faith critique, when you’ll have more spread and influence being lazier and meaner?

Summary

This article unveils a major asymmetry in activism. Belief in a cause, especially something like an existential threat, brings intrinsic motivation to spread the word, while disbelief brings a shrug. Thus, in order to receive outsider critiques, some other motivation needs to bridge the motivation gap.

Receiving unpleasant critiques is incredibly frustrating. It’s tempting to just ignore criticism that is needlessly hostile, or fearmongering, or lazy, or mean-spirited, or politically/financially biased.

But the result is that you ignore people that are motivated by dislike, or fear, or entertainment, or money or tribalism. As a result, you ignore near-everyone that would care enough about the subject to criticize it.

If a cause has a motivation gap, you don’t have to throw up your hands in the air and declare that there’s no point trying to find the truth. But you do have to take it into account, because it filters which arguments get to you, and their quality.

To address the issue, you can try and stomach the hostile articles and pick out the good points from them, or seek out neutral parties and pay them to evaluate the issue, or extra signal boost the high effort good faith critiques you do find. EA has done some of this, but there is still a vast motivation gulf between the believers and the skeptics. Until that situations ends, do not be surprised that the critiques you see seem lazy and hostile.