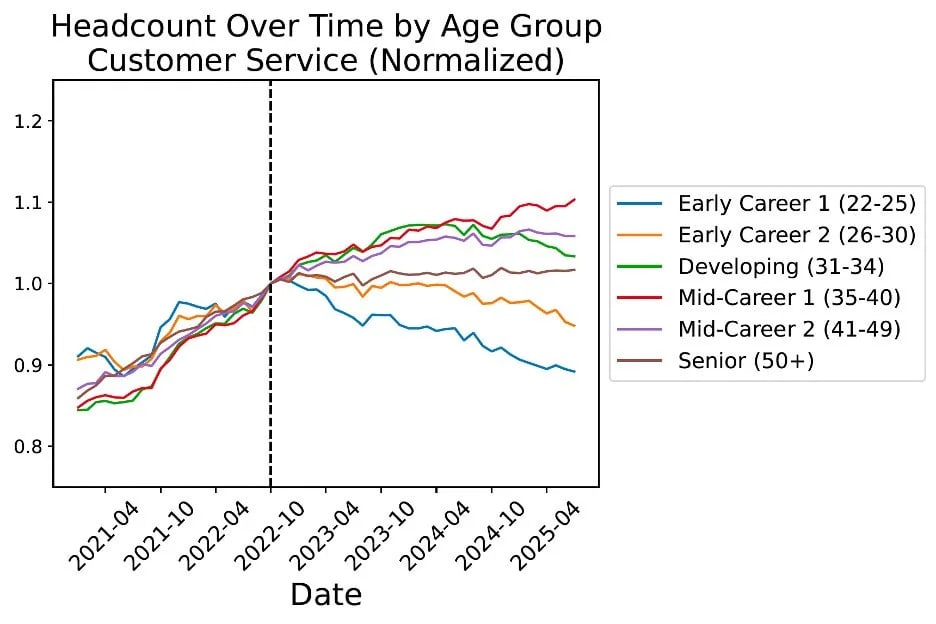

FWIW: These types of graphs with normalization to 1 at one point in the middle and a larger right vs. left can be at least slightly misleading, and I think here it may be - at least slightly, quantitatively; not claiming it removes any '2022 changed it' fully, but makes it considerably less obivious than it looks upon shallow glance: Slightly less obvious to the eye one spots on the LHS the rather exact inverse of the RHS, and actually, if on the RHS you only go out by the same amount as on the LHS, yes RHS is still bit wider but really not insanely much wider anymore.

I reckon easier to check whether trends really abrupbly changed would be:

- proper diff-in-diff analysis, or

- at least also plot the same graph with normalization basis 1.0 say in Jan 2021. Then your eye can actually more easily tell you whether it's really so obvious curvatures changed 'unexpectedly' in 2022 or not, in this particular data constellation

(Not meaning to challenge the general story, I think it still make sense, from theory, anecdotes, and maybe this data to some degree still)

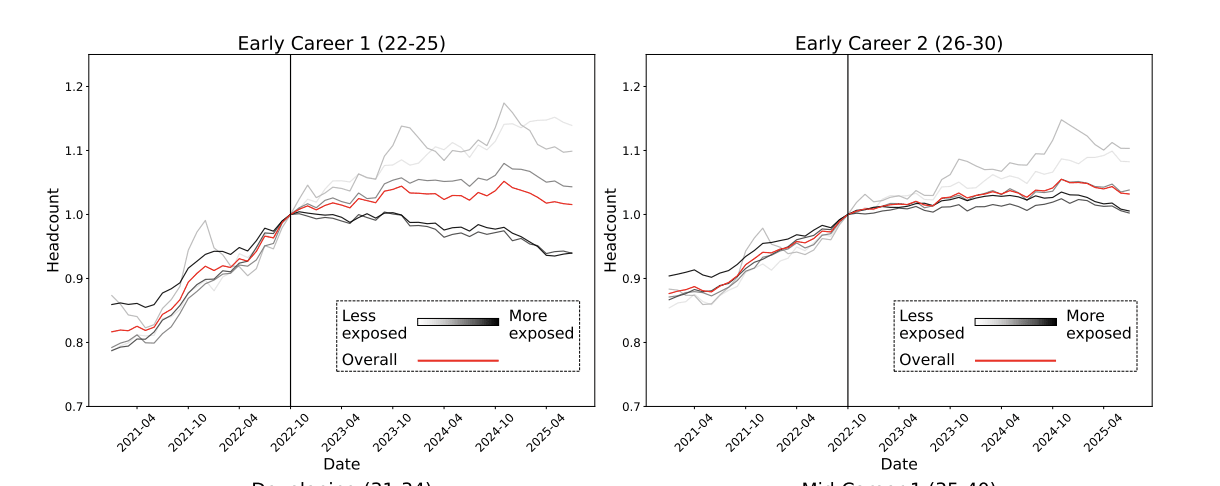

Yeah, those graphs look kind of off. In particular: it supposedly started happening in October 2022? That's pre-GPT-4, and GPT-4 was very barely able to code anything useful. I don't buy that GPT-3.5, effectively the proof-of-concept technical demo, had this sort of effect.

I guess maybe companies recognized where AI progress was headed and foresightfully downscaled their hiring practices in expectation of AI advancing faster than early-career humans can be trained? I, likewise, don't buy this level of industry-wide foresight.

My guess is that "2022 changed it" because of e. g. the Russia-Ukraine war and general rising world instability, not because of AI.

I had the same thought. Some of the graphs, on first glance seem to have an inflection point at ChatGPT release, but looking more seem like the trend started before ChatGPT. Like these seem to show even at the beginning in early 2021 more exposed jobs were increasing at a slower rate than less exposed jobs. I also agree the story could be true, but I'm not sure these graphs are strong evidence without more analysis.

Either it should be 15% instead of 11% or I need some more explanation

So the 13% could be an 11% decline in some areas and a 2% increase in other larger areas, where they cancel out

- Yes, definitely, in terms of for any given job that exists finding the job and getting hired. That’s getting harder. AI is most definitely screwing up that process.

- Yes, probably, in terms of employment in automation-impacted sectors. It always seemed odd to think otherwise, and this week’s new study has strong evidence here.

- Maybe, overall, in terms of the jobs available (excluding search and matching effects from #1), because AI should be increasing employment in areas not being automated yet, and that effect can be small and still dominate.

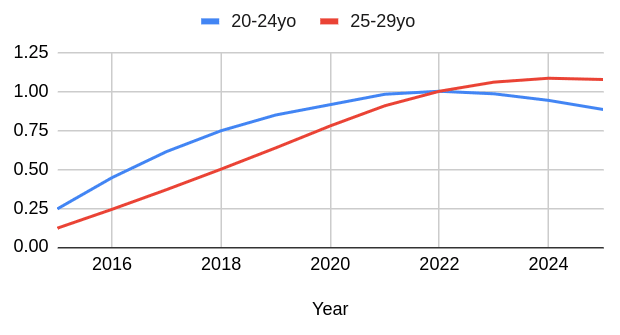

The claims go back and forth on the employment effects of AI. As Derek Thompson points out, if you go by articles in the popular press, we’ve gone from ‘possibly’ to ‘definitely yes’ to ‘almost certainly no’ until what Derek describes as this week’s ‘plausibly yes’ and which others are treating as stronger than that. It’s weird to pull an ‘I told you all so’ when what you said was ‘I am confused and you all are overconfident’ but yeah, basically. The idea that this was ‘well and truly settled’ always seemed absurd to me even considering present effects, none of these arguments should have filled anyone with confidence and neither should the new one, and this is AI so even if it definitively wasn’t happening now who knows where we would be six months later. People changing their minds a lot reflects, as Derek notes, the way discovery, evaluation, discourse and science are supposed to work, except for the overconfidence. Most recently before this week we had claims that what looks like effects of AI automation are delayed impacts from Covid, various interest rate changes, existing overhiring or other non-AI market trends. The new hotness is this new Stanford study from Brynjolfsson, Chandar and Chen: Effects acting through employment rather than compensation makes sense since the different fields are competing against each other for labor and wages are sticky downwards even across workers. Note the y-axis scale on the graphs, but that does seem like a definitive result. It seems far too fast and targeted to be the result of non-AI factors. There’s always that battle between ‘our findings are robust to various things’ and ‘your findings go away when you account for this particular thing in this way,’ and different findings appear to contradict. I don’t know for sure who is right, but I was convinced by their explanation of why they have better data sources and thus they’re right and the FT study was wrong, in terms of there being relative entry-level employment effects that vary based on the amount of automation in each sector. Areas with automation from AI saw job losses at entry level, whereas areas with AI amplification saw job gains, but we should expect more full automation over time. There’s the additional twist that a 13 percent decline in employment for the AI-exposed early-career jobs does not mean work is harder to find. Everyone agrees AI will automate away some jobs. The bull case for employment is not that those jobs don’t go away. It is that those jobs are replaced by other jobs. So the 13% could be an 11% decline in some areas and a 2% increase in other larger areas, where they cancel out. AI is driving substantial economic growth already which should create jobs. We can’t tell. There is one place I am very confident AI is making things harder. That is the many ways it is making it harder to find and get hired for what jobs do exist. Automated job applications are flooding and breaking the job application market, most of all in software but across the board. Matching is by all reports getting harder rather than easier, although if you are ahead of the curve on AI use here you presumably have an edge. Predictions are hard, especially about the future, but I would as strongly as always disagree with this advice from Derek Thompson: Predicting the future is hard in some ways, but that is no reason to throw up one’s hands and pretend to know nothing. We can especially know big things based on broad trends, destinations are often clearer than the road towards them. And in the age of AI, while predicting the present puts you ahead of many, we can know for certain many ways the future will not look like the present. The most important and in some ways easiest things we can say involve what would happen with powerful or transformational AI, and that is really important, the only truly important thing, but in this particular context that’s not important right now. If by the future we do mean the effect on jobs, and we presume that the world is not otherwise transformed so much we have far bigger problems, we can indeed still say many things. At minimum, we know many jobs will be amplified or augmented, and many more jobs will be fully automated or rendered irrelevant, even if we have high uncertainty about which ones in what order how fast. We know that there will be some number of new jobs created by this process, especially if we have time to adjust, but that as AI ‘automates the new jobs as well’ this will get harder and eventually break. And we know that there is a lot of slack for an increasingly wealthy civilization to hire people for quite a lot of what I call ‘shadow jobs,’ which are jobs that would already exist except labor and capital currently choose better opportunities, again if those jobs too are not yet automated. Eventually we should expect unemployment. Getting more speculative and less confident, earlier than that, it makes sense to expect unemployment for those lacking a necessary threshold of skill as technology advances, even if AI wasn’t a direct substitute for your intelligence. Notice that the employment charts above start at age 22. They used to start at age 18, and before that even younger, or they would have if we had charts back then.