I really wish I could agree. I think we should definitely think about flourishing when it's a win/win with survival efforts. But saying we're near the ceiling on survival looks wildly too optimistic to me. This is after very deeply considering our position and the best estimate of our odds, primarily surrounding the challenge of aligning superhuman AGI (including surrounding societal complications).

There are very reasonable arguments to be made about the best estimate of alignment/AGI risk. But disaster likelihoods below 10% really just aren't viable when you look in detail. And it seems like that's what you need to argue that we're near ceiling on survival.

The core claim here is "we're going to make a new species which is far smarter than we are, and that will definitely be fine because we'll be really careful how we make it" in some combination with "oh we're definitely not making a new species any time soon, just more helpful tools".

When examined in detail, assigning a high confidence to those statements is just as silly as it looks at a glance. That is obviously a very dangerous thing and one we'll do pretty much as soon as we're able.

90% plus on survival looks like a rational view from a distance, but there are very strong arguments that it's not. This won't be a full presentation of those arguments; I haven't written it up satisfactorily yet, so here's the barest sketch.

Here's the problem: The more people think seriously about this question, the more pessimistic they are.

And time-on-task is the single most important factor for success in every endeavor. It's not a guarantee but it's by far the most important factor. It dwarfs raw intelligence as a predictor of success in every domain (although the two are multiplicative).

The "expert forecasters" you cite don't have nearly the time-on-task of thinking about the AGI alignment problem. Those who actually work in that area are very systematically more pessimistic the longer and more deeply we've thought about it. There's not a perfect correlation, but it's quite large.

This should be very concerning from an outside view.

This effect clearly goes both ways, but that only starts to explain the effect. Those who intuitively find AGI very dangerous are prone to go into the field. And they'll be subject to confirmation bias. But if they were wrong, a substantial subset should be shifting away from that view after they're exposed to every argument for optimism. This effect would be exaggerated by the correlation between rationalist culture and alignment thinking; valuing rationality provides resistance (but certainly not immunity!) to motivated reasoning/confirmation bias by aligning ones' motivations with updating based on arguments and evidence.

I am an optimistic person, and I deeply want AGI to be safe. I would be overjoyed for a year if I somehow updated to only 10% chance of AGI disaster. It is only my correcting for my biases that keeps me looking hard enough at pessimistic arguments to believe them based on their compelling logic.

And everyone is affected by motivated reasoning, particularly the optimists. This is complex, but after doing my level best to correct for motivations, it looks to me like the bias effects have far more leeway to work when there's less to push against. The more evidence and arguments are considered, the less bias takes hold. This is from the literature on motivated reasoning and confirmation bias, which was my primary research focus for a few years and a primary consideration for the last ten.

That would've been better as a post or a short form, and more polished. But there it is FWIW, a dashed-off version of an argument I've been mulling over for the past couple of years.

I'll still help you aim for flourishing, since having an optimistic target is a good way to motivate people to think about the future.

Thanks. On the EA Forum Ben West points out the clarification: I'm not assuming x-risk is lower than 10%; in my illustrative example I suggest 20%. (My own views are a little lower than that, but not an OOM lower, especially given that this % is about locking into near-0 value futures, not just extinction.) I wasn't meaning to be placing a lot of weight on the superforecasters' estimates.

Actually, because I ultimately argue that Flourishing is only 10% or less, for this part of the argument to work (i.e., for Flourishing to be be greater in scale than Surviving), I only need x-risk this century to be less than 90%! (Though the argument gets a lot weaker the higher your p(doom)).

The point is that we're closer to the top of the x-axis than we are to the top of the y-axis.

Thank you! I saw that comment and responded there. I said that really clarified the argument and that given that clarification, I largely agree.

My one caveat is noting that if we screw up alignment we could easily kill more than our own chance at flourishing. I think it's pretty easy to get a paperclipper expanding at near-C and snuffing out all civilizations in our light cone before they get their chance to prosper. So raising our odds of flourishing should be weighed against the risk of messing up a bunch of other civilizations chances. One likely non-simulation answer to the Fermi paradox is that we're early to the game. We shouldn't lose big if it keeps others from getting to play.

I hadn't considered this tradeoff closely because in my world models survival and flourishing are still closely tied together. If we solve alignment we probably get near-optimal flourishing. If we don't, we all die.

I realize there's a lot of room in between; that model is down to the way I think goals and alignment and human beings work. I think intent alignment is more likely, which would put (a) human(s) in charge of the future. I think most humans would agree that flourishing sounds nice if they had long enough to contemplate it. Very few people are so sociopathic/sadistic that they'd want to not allow flourishing in the very long term.

But that's just one theory! It's quite hard to guess and I wouldn't want to assume that's correct.

I'll look in more depth at your ideas of how to play for a big win. I'm sure most of it is compatible with trying our best to survive.

What do you mean by solve alignment? What is your optimal world? What you consider “near-optimal flourishing” is likely very different than many other people’s ideas of near-optimal flourishing. I think people working on alignment are just punting on this issue right now while they figure out how to implement intent and value alignment but I assume there will be a lot of conflict about what values a model will be aligned to and who a model will be aligned to if/when we have the technical ability to align powerful AIs.

Does the above chart assume all survival situations are better than non-survival? Because that is a DANGEROUS assumption to make.

I agree that we should shift our focus from pure survival to prosperity. But I disagree with the dichotomy that the author seems to be proposing. Survival and prosperity are not mutually exclusive, because long-term prosperity is impossible with a high risk of extinction.

Perhaps a more productive formulation would be the following: “When choosing between two strategies, both of which increase the chances of survival, we should give priority to the one that may increase them slightly less, but at the same time provides a huge leap in the potential for prosperity.”

However, I believe that the strongest scenarios are those that eliminate the need for such a compromise altogether. These are options that simultaneously increase survival and ensure prosperity, creating a synergistic effect. It is precisely the search for such scenarios that we should focus on.

In fact, I am working on developing one such idea. It is a model of society that simultaneously reduces the risks associated with AI and destructive competition and provides meaning in a world of post-labor abundance, while remaining open and inclusive. This is precisely in the spirit of the “viatopias” that the author talks about.

If this idea of the synergy of survival and prosperity resonates with you, I would be happy to discuss it further.

Great work as always. I'm not sure if I agree that we should be focusing on flourishing, conditional on survival. I think a bigger risk would be risks of astronomical suffering which seem like almost the default outcome. Eg digital minds, wild animals in space colonization, and unknown-unknowns. It's possible that the interventions would be overlapping but I am skeptical.

I also don't love the citations for a low p(doom). Toby Ord's guess was from 2020, the Super Forecaster survey from 2022 and prediction markets aren't really optimized for this sort of question. Something like Eli Lifland's guess or the AI Impacts Surveys are where I would start as a jumping off point.

Today, Forethought and I are releasing an essay series called Better Futures, here.[1] It’s been something like eight years in the making, so I’m pretty happy it’s finally out! It asks: when looking to the future, should we focus on surviving, or on flourishing?

In practice at least, future-oriented altruists tend to focus on ensuring we survive (or are not permanently disempowered by some valueless AIs). But maybe we should focus on future flourishing, instead.

Why?

Well, even if we survive, we probably just get a future that’s a small fraction as good as it could have been. We could, instead, try to help guide society to be on track to a truly wonderful future.

That is, I think there’s more at stake when it comes to flourishing than when it comes to survival. So maybe that should be our main focus.

The whole essay series is out today. But I’ll post summaries of each essay over the course of the next couple of weeks. And the first episode of Forethought’s video podcast is on the topic, and out now, too.

The first essay is Introducing Better Futures: along with the supplement, it gives the basic case for focusing on trying to make the future wonderful, rather than just ensuring we get any ok future at all. It’s based on a simple two-factor model: that the value of the future is the product of our chance of “Surviving” and of the value of the future, if we do Survive, i.e. our “Flourishing”.

(“not-Surviving”, here, means anything that locks us into a near-0 value future in the near-term: extinction from a bio-catastrophe counts but if valueless superintelligence disempowers us without causing human extinction, that counts, too. I think this is how “existential catastrophe” is often used in practice.)

The key thought is: maybe we’re closer to the “ceiling” on Survival than we are to the “ceiling” of Flourishing.

Most people (though not everyone) thinks we’re much more likely than not to Survive this century. Metaculus puts *extinction* risk at about 4%; a survey of superforecasters put it at 1%. Toby Ord put total existential risk this century at 16%.

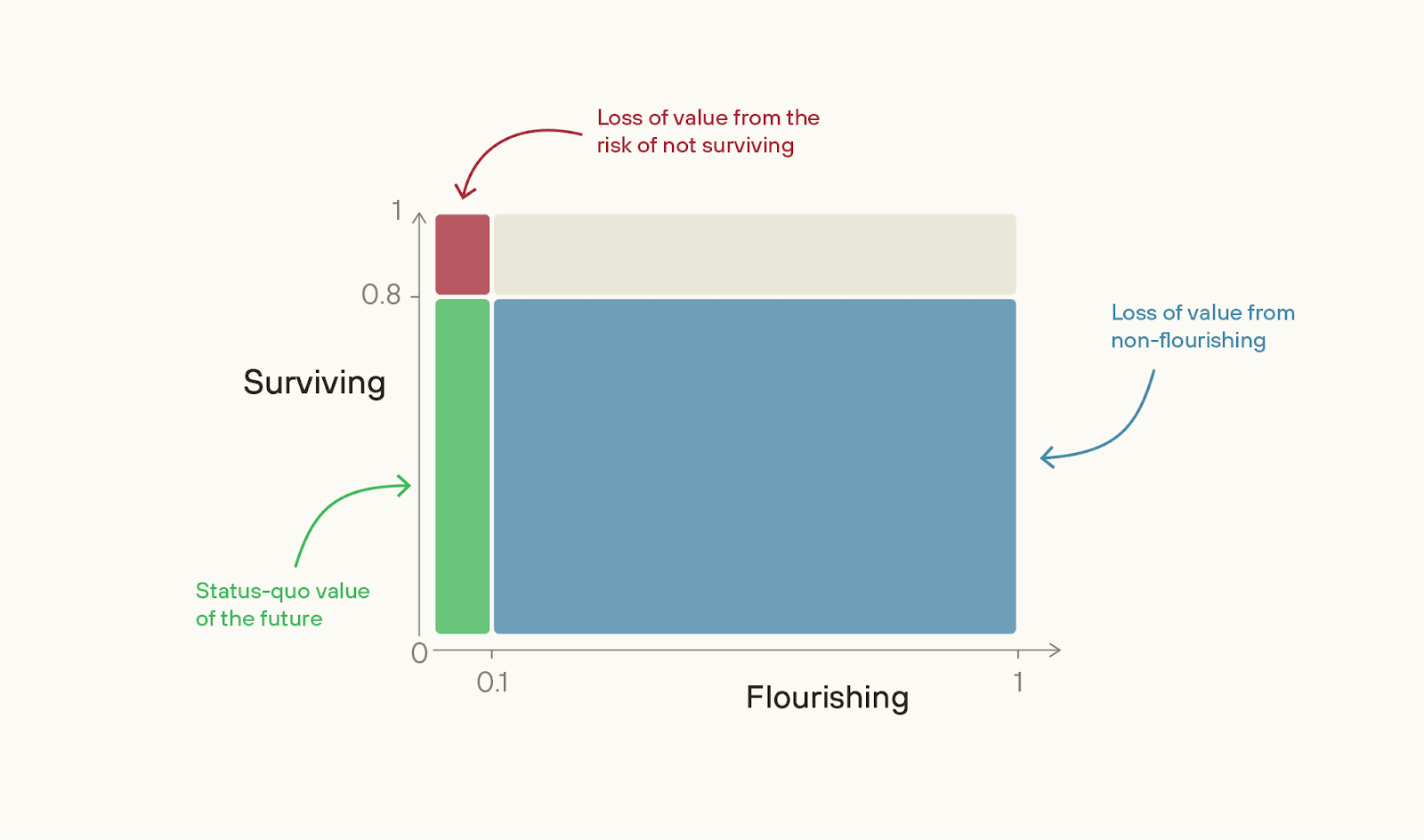

Chart from The Possible Worlds Tree.

In contrast, what’s the value of Flourishing? I.e. if near-term extinction is 0, what % of the value of a best feasible future should we expect to achieve? In the next two essays that follow, Fin Moorhouse and I argue that it’s low.

And if we are farther from the ceiling on Flourishing, then the size of the problem of non-Flourishing is much larger than the size of the problem of the risk of not-Surviving.

To illustrate: suppose our Survival chance this century is 80%, but the value of the future conditional on survival is only 10%.

If so, then the problem of non-Flourishing is 36x greater in scale than the problem of not-Surviving.

(If you have a very high “p(doom)” then this argument doesn’t go through, and the essay series will be less interesting to you.)

The importance of Flourishing can be hard to think clearly about, because the absolute value of the future could be so high while we achieve only a small fraction of what is possible. But it’s the fraction of value achieved that matters. Given how I define quantities of value, it’s just as important to move from a 50% to 60%-value future as it is to move from a 0% to 10%-value future.

We might even achieve a world that’s common-sensically utopian, while still missing out on almost all possible value.

In medieval myth, there’s a conception of utopia called “Cockaigne” - a land of plenty, where everyone stays young, and you could eat as much food and have as much sex as you like.

We in rich countries today live in societies that medieval peasants would probably regard as Cockaigne, now. But we’re very, very far from a perfect society. Similarly, what we might think of as utopia, today, could nonetheless barely scrape the surface of what is possible.

All things considered, I think there’s quite a lot more at stake when it comes to Flourishing than when it comes to Surviving.

I think that Flourishing is likely more neglected, too. The basic reason is that the latent desire to Survive (in this sense) is much stronger than the latent desire to Flourish. Most people really don’t want to die, or to be disempowered in their lifetimes. So, for existential risk to be high, there has to be some truly major failure of rationality going on.

For example, those in control of superintelligent AI (and their employees) would have to be deluded about the risk they are facing, or have unusual preferences such that they're willing to gamble with their lives in exchange for a bit more power. Alternatively, look at the United States’ aggregate willingness to pay to avoid a 0.1 percentage point chance of a catastrophe that killed everyone - it’s over $1 trillion. Warning shots could at least partially unleash that latent desire, unlocking enormous societal attention.

In contrast, how much latent desire is there to make sure that people in thousands of years’ time haven’t made some subtle but important moral mistake? Not much. Society could be clearly on track to make some major moral errors, and simply not care that it will do so.

Even among the effective altruist (and adjacent) community, most of the focus is on Surviving rather than Flourishing. AI safety and biorisk reduction have, thankfully, gotten a lot more attention and investment in the last few years; but as they do, their comparative neglectedness declines.

The tractability of better futures work is much less clear; if the argument falls down, it falls down here. But I think we should at least try to find out how tractable the best interventions in this area are. A decade ago, work on AI safety and biorisk mitigation looked incredibly intractable. But concerted effort *made* the areas tractable.

I think we’ll want to do the same on a host of other areas — including AI-enabled human coups; AI for better reasoning, decision-making and coordination; what character and personality we want advanced AI to have; what legal rights AIs should have; the governance of projects to build superintelligence; deep space governance, and more.

On a final note, here are a few warning labels for the series as a whole.

First, the essays tend to use moral realist language - e.g. talking about a “correct” ethics. But most of the arguments port over - you can just translate into whatever language you prefer, e.g. “what I would think about ethics given ideal reflection”.

Second, I’m only talking about one part of ethics - namely, what’s best for the long-term future, or what I sometimes call “cosmic ethics”. So, I don’t talk about some obvious reasons for wanting to prevent near-term catastrophes - like, not wanting yourself and all your loved ones to die. But I’m not saying that those aren’t important moral reasons.

Third, thinking about making the future better can sometimes seem creepily Utopian. I think that’s a real worry - some of the Utopian movements of the 20th century were extraordinarily harmful. And I think it should make us particularly wary of proposals for better futures that are based on some narrow conception of an ideal future. Given how much moral progress we should hope to make, we should assume we have almost no idea what the best feasible futures would look like.

I’m instead in favour of what I’ve been calling viatopia, which is a state of the world where society can guide itself towards near-best outcomes, whatever they may be. Plausibly, viatopia is a state of society where existential risk is very low, where many different moral points of view can flourish, where many possible futures are still open to us, and where major decisions are made via thoughtful, reflective processes.

From my point of view, the key priority in the world today is to get us closer to viatopia, not to some particular narrow end-state. I don’t discuss the concept of viatopia further in this series, but I hope to write more about it in the future.

This series was far from a solo effort. Fin Moorhouse is a co-author on two of the essays, and Phil Trammell is a co-author on the Basic Case for Better Futures supplement.

And there was a lot of help from the wider Forethought team (Max Dalton, Rose Hadshar, Lizka Vaintrob, Tom Davidson, Amrit Sidhu-Brar), as well as a huge number of commentators.