Is this the same thing as what the TVTropes people call a Dead Unicorn Trope?

A plot, character, or story element which is parodied or mocked as overused, even though it wasn't in broad use to begin with. The result is a strange metacontextual trick where viewers congratulate themselves on the death of something that never lived (hence the title).

When you hear “stereotype of death” the phrase “malevolent and heartless” may quickly spring to mind, regardless of its accuracy. That’s a stereotype. And the thing you’re stereotyping is also, coincidentally, a stereotype.

Actually that's a stereotype of an archetype; Death as it appears in fiction is an archetype.

I'm under the impression things work like this:

Archetypes are kind of like conventions or mathematical objects with specifications and meta-specifications, especially of types of characters.

Stereotypes are the popular beliefs about a thing, whether or not they're true.

Stereotypes of stereotypes would look something more like popular beliefs about popular beliefs.

Stereotypes of archetypes are popular beliefs about the pieces of (esp. well-known) broad character type ontologies.

What is a stereotypical male action hero?

Tough. Stiff upper lip. Never cries, never loses his cool, never loses his temper. Never has mental illness, never suffers mental trauma. Handles everything. Knows how to do everything. Never gets in over his head. Never relies on others for help.

The answer to this problem is that few action heroes have all of these traits, but a fair number of them have most of those traits. When people think of an average action hero, the fact that each individual hero lacks a small portion of the traits is going to get averaged out, so the "average" hero has all the traits even though each particular hero only has most.

As for the Death example,

I’m sure there are occasional negative portrayals ... but those seldom qualify as “characters.”

basically defines away the counterexamples. People saying that death is normally portrayed as cruel and evil probably are thinking of those examples, even if they don't count as "characters". Furthermore, excluding examples that aren't "characters" inherently stacks the deck towards happy Deaths because making Death have feelings is characterization, so the same example wouldn't count if Death is evil but would count if Death is affable.

I wasn't excluding evil deaths on the grounds of being simplistic; I was referring to a depiction of death that appears for a few minutes in a cartoon to chase someone down, or something of that nature. I'm sure I've seen a Bugs Bunny cartoon where he's chased by the grim reaper, and I have a few childhood memories of cartoon characters being chased by Death on TV. But none of these depictions lasted more than a few minutes. I'm excluding them not on the grounds of being simplistic portrayals, but on the grounds of them making very brief appearances with little lasting significance.

I think partly what you're running into is that we live in a postmodern age of storytelling. The classic fairytales where the wicked wolf dies (three little pigs)(red riding hood) or the knight gets the princess after bravely facing down the dragon (George and the dragon) are being subverted because people got bored of those stories, and they wanted to see a twist, so we get something like Shrek - The ogre is hired by the king to rescue the princess from the dragon, but ends up rescuing the princess from the king.

The original archetypes DID exist in stories, but they are rarely used today without some kind of twist. This has happened to the extent that our culture is saturated with this, the twist is now expected and it's possible to forget that the archetypes ever existed as a common theme.

Essentially I think you're finding instances where the archetype doesn't match the majority of modern examples. This is because the archetype hasn't changed, but media referencing that archetype rarely uses it directly without subverting it somewhat.

(Edit)

Thinking about it further, the fairytales I talked about also subvert expectations- hungry wolves normally eat pigs, for example. Those archetypes come from the base level of real life though. It would be common knowledge that wolves will opportunistically prey on livestock. This makes a story about pigs building little houses and then luring the wolf into a cooking pot fun because it reverses the normal roles. When it becomes common to have the wicked wolf lose, though, the story becomes expected and stale. Then someone twists it a little more and you get Shrek, or Zootopia (where (spoilers) the villain turns out to be a sheep)

I think partly what you're running into is that we live in a postmodern age of storytelling.

This. Postmodern stories expect the audience to be familiar with the thing they subvert, but this expectation starts to fail when they become more successful than the thing.

(This does not have to be a fatal flaw. For example, Magical Girl Madoka is a subversion of the magical girl trope, but it makes sense even to an audience unfamiliar with the trope. Probably because the first two and half episodes kinda follow the trope, before the story starts to deviate from it. This is different from opposing the trope from the very start.)

I sometimes feel weird when I watch a movie for kids together with my children, as I see that the movie is subverting a trope that I am familiar with... but they are not. I wonder what kind of message they get from the movie; whether they somehow get it anyway, or it's just "random things happen for random reasons".

(My older daughter once asked me, why are adult males always depicted in movies as idiots. I guess the movie producers still see themselves as transgressive heroes who defy the popular stereotypes, but in fact they are just a part of the new monoculture. These days, a truly shocking story would be about a brave boy who succeeds to overcome adversity alone, and gets a girl... who does not turn out to be a lesbian.)

I think stereotype of the stereotype is a mouthful and also not very clear, and thus present the term "presumed stereotype". Using this in a live conversation should immediately signal to the other party what you mean (that their description is what everyone presumes to be the stereotype, but the actual stereotype (which you would then describe to them) is something else, maybe even the polar opposite).

I’m sure that someone, somewhere has written a book or directed a movie where Death is not, basically, a kind hardworking man with a job to do. I’ve never read the books, or seen the movies, though.

May I recommend Final Destination and its sequels?

Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality doesn't really "characterize" individual Dementors but they are basically just horrible holes in reality, which seems proper since the death of persons should be rejected as having no proper place in a fully happy and healthy ordering of a world where all the Big Problems have been Solved.

Also in the TV version of Good Omens he's basically just bad. In the book this portrayal is softened a bit.

it doesn't seem right to add a level of meta here. one is the actual character, one is the stereotype of the character. one rarely sees the stereotypical death character, but one frequently sees a death character that subverts the stereotype. no need to add "of the stereotype", imo it just makes an obvious concept require further explaining. it's a reasonable point, though. good post, i just don't think it needs a new name allocation.

I’m sure that someone, somewhere has written a book or directed a movie where Death is not, basically, a kind hardworking man with a job to do. I’ve never read the books, or seen the movies, though.

This is a comic, but Judge Death from the world of Judge Dredd is absolutely malign and the enemy of all mankind. Then there are also the Dementors from HPMOR.

A few others

- Death from the Castlevania series is simply evil

- Death in Supernatural is debatable. He is made sympathetic at some point but in his first appearance he is about to destroy Chicago then changes his mind with the reason "I like the pizza".

- In the Thorgal series it is a complete asshole inventing new ways to put mortals close to being dead without being fully dead, for fun.

Also I think there are various stories and depictions where death is not a character but makes an appearance in some way, maybe purely symbolic, and seems to be evil or to enjoy humans dying. I am sure I have seen many depictions of laughing death as a metaphor of scenes of carnage (the first that comes to mind is a double page in the Darkmoon Chronicles where the burning of cities is illustrated with a laughing/smiling reaper).

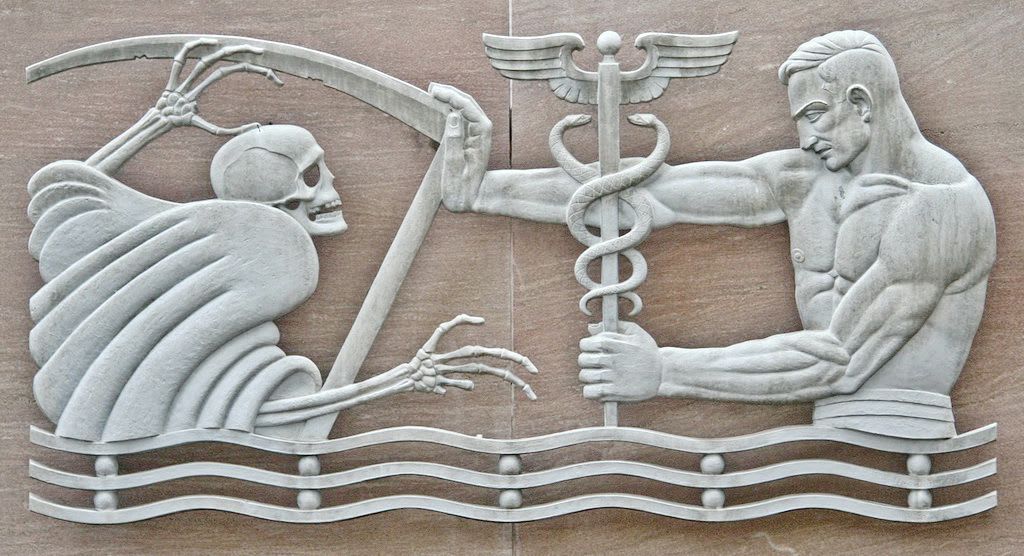

So perhaps we could say that when Death is made a real character in stories it is more often than not a "kind hardworking man with a job to do"; but at the same time most depictions of the reaper are not characters but rather use a simple portrayal as a metaphor for evil and slaughter. Somewhat in the spirit of this famous image

If this is correct I think we can see where the friend in the post was coming from

“It’s nice to see a portrayal of Death that doesn’t paint him as some mindless villain, and actually gives him some characterization.”

I like this concept and the name you've given it.

However, I want to push back against your "action hero archetype" claims.

"Action hero" immediately makes me think of movies, rather than the book. And a lot of the older James Bond films fit this stereotype.

I also swear I've seen a lot of "junk food" action movies that fit this stereotype, but it's hard for me to remember exactly which ones off the top of my head.

It's plausible to me that people remember the films you named precisely because they were more complex.

I wouldn't class most of the examples given in this post as stereotypical male action heroes.

Rambo was the first example I thought of, and then most roles played by Jason Statham, Bruce Willis, Arnold Shwarzeneggar or Will Smith. I also don't think the stereotype is completely emotionless, just violent, tough and motivated, capable of anything. They tend to have fewer vulnerable moments and only cry when someone they love dies or something. They don't cry when they have setbacks to their plans or are upset by an insult someone shouts at them, like normal people might. They certainly don't cry when they lose their keys or forget somebody's birthday, or feel pressure to do well in an exam.

The male action hero stereotype is definitely a thing, even if it’s not perfectly adhered to 100%.

Examples: Rambo (first films), John McClane, James Bond (Sean Connery era), Chuck Norris, Steven Seagal and Jean-Claude Van Damme in films like Under Siege and Bloodsport, Jack Reacher

While I'm unfamiliar with most fictional portrayals of Death including the ones you mention, I will say that I played Death on stage for a high school production of a one-act play written by one of my theater classmates, and the character I played was a neutral-to-good comical bumbler just trying to act on his boss's orders. My classmate had a creative streak, obviously, but I don't think she was being particularly transgressive; probably she was influenced by several neutral-to-good just-doing-his-job Death characters from existing fictional media.

I want to define a new term that will be useful in the discourse.

Imagine you landed in a foreign country with dogs, but with no word for dogs. You would see these things, and want to talk about them. You would like to be able to tell people whether they can bring dogs into your house, but you can’t, because there isn’t any word for “dog.” You’d like to ask if you can pet someone’s dog, but you can’t do that either, because when you ask “can I pet your dog?” they say “pet my what?” It would get pretty frustrating.

This is how I feel about a certain phenomenon I’ve noticed over the last year or so. I notice it all the time—It’s as ubiquitous in society as dogs are, and I see it just about as often—but there isn’t a word for it. People seem to make the same error of judgement over and over, and I want to talk about this error. There’s a lot I want to say about it. I want to be able to point out when someone is making the mistake. I want to ask people about whether I’m making the mistake. I want to talk about how some people seem to see very clearly, and make the mistake very rarely. Others seem to be very cloudy-eyed where this mistake is concerned, and they make it very often.

So, I’m going to make up a new term. The term is “The Stereotype of the Stereotype.” The mistake I’m talking about is not “The Stereotype of the Stereotype.” The Stereotype of the Stereotype is a noun. This mistake is a verb. The verb is “confusing the stereotype with The Stereotype of the Stereotype.”

Mixing up ‘the stereotype’ with ‘The Stereotype of the Stereotype’ is as significant a mistake as seeing the word “rainstorm,” and opening your umbrella. You aren’t allowed to mix up levels that way. The stereotype is the stereotype. The Stereotype of the The Stereotype is The Stereotype of the The Stereotype. And they are as different as a rainstorm, and the word “Rainstorm.”

Let’s use some examples to define this term “The Stereotype of the Stereotype.”

-

Sir Terrence Pratchett was a British satirical fantasy author, most famous for his Discworld series of books.

There are 41 of these books. Most of them follow distinct arrangements of characters. For example, eight of them follow a man named Sam Vimes. Another five follow a girl named Tiffany Aching. However, there’s one character who shows up in nearly every book. His name is Death.

Death appears in 39 of the 41 books. With a few exceptions of Early Installment Weirdness, Death has a very consistent characterization: He is fair, reasonable, workmanlike, sympathetic, and—in an alien way—kind. He helps people in need. He can be relied upon to do the right thing. He isn’t responsible for killing people, he just collects their souls. He’s about as malicious as a garbageman.

This makes Death a compelling, interesting, and likeable character. The books which follow him, such as Mort or Reaper Man, are compelling and interesting. He forms an enjoyable side dish to novels in which he is only a minor character. There’s nothing wrong with Death.

So when a friend of mine read Guards, Guards!, one of the Discworld books, and said he liked the character of Death, I wasn’t surprised. I liked him too.

But then this friend of mine said something strange. He said (and I’m only paraphrasing here): “It’s nice to see a portrayal of Death that doesn’t paint him as some mindless villain, and actually gives him some characterization.”

It took some doing to get that idea into my head, so I paused for a few seconds before I said:

“Can you think of a single example—in all of myth and all of fiction—where Death has been portrayed as a mindless villain?”

He couldn’t.

I’m sure there is some mythology out there with which I am unfamiliar where Death is portrayed as a destructive, unfeeling, malevolent force of evil. I’m sure there are novels I have not read where he is psychopathic and cruel. I’m sure that someone, somewhere has written a book or directed a movie where Death is not, basically, a kind hardworking man with a job to do. I’ve never read the books, or seen the movies, though.

On the other hand, I was able to name half a dozen works where Death is portrayed as friendly and professional, including Greek, Norse, and Egyptian mythology, but also the children’s television show The Grimm Adventures of Billy and Mandy and the computer game Manual Samuel. Ryuk in the television show Death Note is depicted as a demon partially responsible for all human death, and he is a comical, likeable character. Ditto the other death demon in the same television show.

I’m sure there are occasional negative portrayals of the Grim Reaper which I’ve seen in cartoons—one of them probably chases Bugs Bunny around—but those seldom qualify as “characters.” Are there any characterized portrayals of Death—ever—that show him as the malevolent figure my friend imagined? I can think of only one, and it's a longshot, too. Hades from the children’s film Hercules. In any case, Hades is the prince of the underworld, not Death himself. He’s closer to a dictator than a murderer.

So where did my friend get this nonsense he was spouting about Death being always portrayed this way? Even he couldn’t think of a single example of Death being portrayed as a mindless killer.

In fact, Death is often portrayed in a single, stereotyped fashion. It’s just that this stereotype is precisely the opposite of what my friend imagined! Death is always portrayed as sympathetic, complex, and fundamentally either good or neutral.

Ah, but here’s the rub:

The Stereotype of Death is sympathetic, complex, and fundamentally either good or neutral. We can observe this very easily; any time someone sets out to imagine Death for a book or a TV show, this is what they come up with! But the stereotype of the stereotype of Death is something completely different. If you ask someone “what is the stereotype of Death as he is portrayed in fiction” I bet there’s a good chance they’ll say “Malevolent and heartless.”

That’s because the stereotype has a stereotype of its own.

When you hear “cop” the phrase “donut-eating” may quickly spring to mind, regardless of its accuracy. That’s a stereotype.

When you hear “stereotype of death” the phrase “malevolent and heartless” may quickly spring to mind, regardless of its accuracy. That’s a stereotype. And the thing you’re stereotyping is also, coincidentally, a stereotype.

-

What is a stereotypical male action hero?

Tough. Stiff upper lip. Never cries, never loses his cool, never loses his temper. Never has mental illness, never suffers mental trauma. Handles everything. Knows how to do everything. Never gets in over his head. Never relies on others for help.

Yeah right.

Let me rattle off some classic male action heroes who I have read/watched.

In no particular order: Luke Skywalker, Joe Turner, Edmund Dantes, Harry Dresden, Baby, James Kirk, John McLean, Douglas Quaid, Han Solo, James Bond, Tarzan, Indiana Jones, Neo, Captain Vimes, Sam Dryden, Travis Chase, Rayland Givens, Sherlock Holmes, R. J. McMurphy, and Michael Corleone.

There is one man on this list who I think might fit this archetype (Holmes.) As for the rest, hah! Forget it.

James Bond, in the novels, routinely cries, vomits, or passes out from fear, shock, or disgust. He loses his temper, trips over his words, is awkward with women, says things which he takes back as being cruel or unsympathetic, changes his mind, gets nervous, gets scared. In Diamonds are Forever he kills two men and feels guilty about it for the rest of the novel. He can’t get the image of their murdered faces out of his head. In Casino Royale he is tortured, and the trauma follows him for the rest of his life. He is permanently humbled.

These are not great novels. They are not even good. James Bond is some of the worst dreck the market has to offer. You might as well read Marmaduke. At least Marmaduke has two things going for it over James Bond: The portrayals of human nature will be more accurate, and the philosophy more advanced.

So if the worst and most boring male action hero in literature is sensitive and emotional, that’s setting the bar pretty low.

Look at the examples on this list that are actually good and you’ll see an even starker contrast. Michael Coreleone spends the whole of the Godfather (book or movie, it doesn’t matter) coming to terms with his responsibilities as an action hero. It conflicts with his better nature. He must shape himself into someone he isn’t in order to do what he thinks is right, and it is profoundly affecting to him. His rich, tortured emotional inner life is the entire subject of the story. Both Bond and Michael rely on others. Bond on his friend Felix and Michael on his wife and family.

John McLean, perhaps the most imitated action hero of the last fifty years, openly weeps, fears for his life, screams, runs away, and second guesses himself.

Where does this idea of the stiff upper lip hero come from? Have you ever actually seen one? Not a parody of one, but an actual example? Sherlock Holmes, maybe. It’s been a while since I read Hound of the Baskervilles. I’ve heard Richard Hannay follows the mold. So does Sam Spade, allegedly. But I’ve been tricked before. I was told James Bond fit the mold, and I believed that—until I read the books.

So: the American male action hero follows a very strongly set mold. An archetype: He doubts himself. He screams when he is in pain, he cries when is sad, he vomits when is shocked or when he exerts himself. He fears for his life. He shows sensitivity and kindness to his family. He second guesses himself. He frequently has no idea what he is supposed to do in any given situation. He relies on his friends and lovers for assistance. He is conflicted about hurting and killing other people.

Almost every male action hero I can think of from the last 200 years conforms to this stereotype—and for good reason, too. Such men make much better, much more compelling heroes than some emotionless rock.

But the emotionless rock, I find, exists largely in theory. It is the stereotype of the stereotype. If you ask someone to describe the stereotype of male action heroes, they’ll describe a stereotype of the stereotype of male action heroes that is stoic, emotionless, and hypercompetent. But actual examples of such heroes are very rare.

-

Of course, sometimes, this concept can be misapplied.

For a long time, I didn’t understand what people meant by a cliche “man wins a woman as a reward” romance plot. Do you know that trope? The man beats the dragon, and as soon as he does, the woman loves him and wants to sleep with him.

When I was 10, I thought this was bullshit. If 10 year old me had known the term “The stereotype of the stereotype,” then he would have used it instantly to describe this. There was this plot which seemed to exist only in complaint-form. No actual story had this plot. It just existed in, you know, complaint-space.

But this does happen. It's just that when I was 10, I had never read these stories. Later, I would read (to take a sampling of the heroes above) Harry Dresden, James Bond, Michael Corelone, and Travis Chase, and watch (to take another sampling) Joe Turner, John McLean, Douglas Quaid, and Indiana Jones. Debatably, you could also include Baby, Tarzan, Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, and even Kirk. Conan the barbarian gets the girl so many times that you need a scorecard to keep track. This trope does exist, it's just that I was in a bubble that isolated me from the trope, without being inside a bubble that isolated me from the complaints about the trope.

-

Why are all my examples fictional?

There are definitely real stereotypes of stereotypes. There are stereotypes of stereotypes in law, politics, history, rhetoric, and religion. But I don't want to polarize this essay. This essay isn’t about defending or attacking a political position—

—Not to say that defending or attacking a political position is beneath me, just that it’s not something I intend to do right this second—

—It’s about adding a tool to our mental toolboxes. That’s all words are. They’re mental tools for communicating to other people, and to ourselves. And If I said something distractingly political, like:

“The stereotype of King Alphonse II’s rulership of Spain is that he was a great king but the stereotype of the stereotype is that he’s a terrible king.”

Then suddenly all the King Alphonse II supporters and King Alphonse II haters would get mad at me, and get mad at the essay, and get mad at the idea.

And I don’t want to alienate people from this concept. I don’t want to alienate anyone from any idea. No matter how repulsive a political position is to me, I want to be able to communicate clearly with the people who have that idea. And I think this idea is very useful in political communication, so it is very important I don’t deny it to large portions of the population by laying out some fool example in the original document.

So I have used only frivolous examples. But that doesn’t mean this concept is only useful for frivolous situations. That would be like saying that, since you practiced your punches and kicks on a straw dummy, you now know only how to fight straw dummies.

-

People mix up the stereotype with The Stereotype of the Stereotype. That’s the problem. The problem is not the existence of The Stereotype of the Stereotype, which can be useful.

If you watch a tiny little old man hobbling down the street in a kung fu movie, everyone understands the difference between the stereotype (the tiny little old man is an unstoppable kung fu badass) and the stereotype of the stereotype (the old man is a feeble little weakling.) We understand that we are supposed to play the role of someone who expects the old man to be a feeble weakling, even though we actually know that in every kung fu movie, the tiny old man is an unstoppable kung fu badass.

The problem comes when a person, deliberately or by accident, confuses the two. They confuse the way things actually tend to be perceived with a perception of how things tend to be perceived.

The most useful response I have to this is the one I mentioned earlier under Death. “Name one.” If someone, perhaps someone who isn’t very genre-canny about kung fu movies, says “but an old man is always a symbol of weakness and feebleness in kung fu films!” try the counter “Name one.” My friend almost instantly realized his error when I asked him to name a single example of Death being portrayed as cold and malevolent.

But really, I have no good response. Asking someone to “name one” works fine, but it doesn’t get across the breadth or depth of the mistake, and it comes across as childish in a real argument.

My hope is, that if you and your interlocutor have both read this essay, your response can be “That’s just The Stereotype of the Stereotype!”

And that will suffice.