If you don't believe in your work, consider looking for other options

I spent 15 months working for ARC Theory. I recently wrote up why I don't believe in their research. If one reads my posts, I think it should become very clear to the reader that either ARC's research direction is fundamentally unsound, or I'm still misunderstanding some of the very basics after more than a year of trying to grasp it. In either case, I think it's pretty clear that it was not productive for me to work there. Throughout writing my posts, I felt an intense shame imagining readers asking the very fair question: "If you think the agenda is so doomed, why did you keep working on it?"[1]

In my first post, I write: "Unfortunately, by the time I left ARC, I became very skeptical of the viability of their agenda."This is not quite true. I was very skeptical from the beginning, for largely similar reasons I expressed in my posts. But first I told myself that I should stay a little longer. Either they manage to convince me that the agenda is sound, or I demonstrate that it doesn't work, in which case I free up the labor of the group of smart people working on the agenda. I think this was initially a somewhat reasonable position, though it was already in large part motivated reasoning.

But half a year after joining, I don't think this theory of change was very tenable anymore. It was becoming clear that our arguments were going in circles. I couldn't convince Paul and Mark (the two people thinking the most about the big picture questions), nor could they convince me. Eight months in, two friends visited me in California, and they noticed that I always derailed the conversation when they asked me about my research. I think that should have been an important thing to notice that I was ashamed to talk about my research to my friends, because I was afraid they would see how crazy it was. I should have quit then, but I stayed for another seven months.

I think this was largely due to cowardice. I'm very bad at coding and all my previous attempts at upskilling in coding went badly.[2] I thought of my main skill as being a mathematician, and I wanted to keep working on AI safety. The few other places one can work as a mathematician in AI safety looked even less promising to me than ARC. I was afraid that if I quit, I wouldn't find anything else to do.

In retrospect, this fear was unfounded. I realized there were other skills one can develop, not just coding. In my afternoons, I started reading a lot more papers and serious blog posts [3] from various branches of AI safety. After a few months, I felt I had much more context on many topics. I started to think more about what I can do with my non-mathematical skills. When I finally started applying for jobs, I got an offer from the European AI Office and UKAISI, and it looked more likely than not that I would get an offer from Redwood. [4]

Other options I considered that looked less promising than the three above, but still better than staying at ARC: Team up with some Hungarian coder friends and execute some simple but interesting experiments I had vague plans for. [5] Assemble a good curriculum for the prosaic AI safety agendas that I like. Apply for a grant-maker job. Become a Joe Carlsmith-style general investigator. Try to become a journalist or an influential blogger. Work on crazy acausal trade stuff.

I still think many of these were good opportunities, and probably there are many others. Of course, different options are good for people with different skill profiles, but I really believe that the world is ripe with opportunities to be useful for people who are generally smart and reasonable and have enough context on AI safety. If you are working on AI safety but don't really believe that your day-to-day job is going anywhere, remember that having context and being ingrained in the AI safety field is a great asset in itself,[6] and consider looking for other projects to work on.

(Important note: ARC was a very good workplace, my coworkers were very nice to me and receptive to my doubts, and I really enjoyed working there except for feeling guilty that my work is not useful. I'm also not accusing the people who continue working at ARC of being cowards in the way I have been. They just have a different assessment of ARC's chances, or work on lower-level questions than I have, where it can be reasonable to just defer to others on the higher-level questions.)

(As an employee of the European AI Office, it's important for me to emphasize this point: The views and opinions of the author expressed herein are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission or other EU institutions.)

- ^

No, really, it felt very bad writing the posts. It felt like describing how I worked for a year on a scheme that was either trying to build perpetuum mobile machines, or trying to build normal cars, I just missed the fact that gasoline exists. Embarrassing either way.

- ^

I don't know why. People keep telling me that it should be easy to upskill, but for some reason it is not.

- ^

I particularly recommend Redwood's blog.

- ^

We didn't fully finish the work trial as I decided that the EU job was better.

- ^

Think of things in the style of some of Owain Evans' papers or experiments on faithful chain of thought.

- ^

And having more context and knowledge is relatively easy to further improve by reading for a few months. It's a young field.

If one reads my posts, I think it should become very clear to the reader that either ARC's research direction is fundamentally unsound, or I'm still misunderstanding some of the very basics after more than a year of trying to grasp it.

I disagree. Instead, I think that either ARC's research direction is fundamentally unsound, or you're still misunderstanding some of the finer details after more than a year of trying to grasp it. Like, your post is a few layers deep in the argument tree, and the discussions we had about these details (e.g. in January) went even deeper. I don't really have a position on whether your objections ultimately point at an insurmountable obstacle for ARC's agenda, but if they do, I think one needs to really dig into the details in order to see that.

(ETA: I agree with your post overall, though!)

That's not how I see it. I think the argument tree doesn't go very deep until I lose the the thread. Here are a few, slightly stylized but real, conversations I had with friends who had no context on what ARC was doing, when I tried to explain our research to them:

Me: We want to to do Low Probability Estimation.

Them: Does this mean you want to estimate the probability that ChatGPT says a specific word after a 100 words on chain of thought? Isn't this clearly impossible?

Me: No, you see, we only want to estimate the probabilities only as well as the model knows.

Them: What does this mean?

Me: [I can't answer this question.]

Me: We want to do Mechanistic Anomaly Detection.

Them: Isn't this clearly impossible? Won't this result in a lot of false positives when anything out of distribution happens?

Me: Yes, why we have this new clever idea of relying on the fragility of sensor tampering, that if you delete a subset of the actions, you will get an inconsistent image.

Them: What if the AI builds another robot to tamper with the cameras?

Me: We actually don't want to delete actions but heuristic arguments for why the cameras will show something, and we want to construct heuristic explanations in a way that they carry over through delegated actions.

Them: What does this mean?

Me; [I can't answer this question.]

Me: We want to create Heuristic Arguments to explain everything the model does.

Them: What does it mean that an argument explained a behavior? What is even the type signature of heuristic arguments? And you want to explain everything a model does? Isn't this clearly impossible?

Me: [I can't answer this question.]

When I was explaining our research to outsiders (which I usually tried to avoid out of cowardice), we usually got to some of these points within minutes. So I wouldn't say these are fine details of our agenda.

During my time at ARC, the majority of my time was spent on asking variations of these three questions from Mark and Paul. They always kindly answered, and the answer was convincing-sounding enough for the moment that I usually couldn't really reply on the spot, and then I went back to my room to think through their answers. But I never actually understood their answers, and I can't reproduce them now. Really, I think that was the majority of work I did at ARC. When I left, you guys should have bought a rock with "Isn't this clearly impossible?" written on it, and that would profitably replace my presence.

That's why I'm saying that either ARC's agenda is fundamentally unsound or I'm still missing some of the basics. What is standing between ARC's agenda collapsing from five minutes of questioning from an outsider is that Paul and Mark (and maybe others in the team) have some convincing-sounding answers to the three questions above. So I would say that these answers are really part of the basics, and I never understood them.

Maybe Mark will show up in the comments now to give answers to the three questions, and I expect the answers to sound kind of convincing, and I won't have a very convincing counter-argument other than some rambling reply saying essentially that "I think this argument is missing the point and doesn't actually answer the question, but I can't really point out why, because I don't actually understand the argument because I don't understand how you imagine heuristic arguments". (This is what happened in the comments on my other post, and thanks to Mark for the reply and I'm sorry for still not understanding it.) I can't distinguish whether I'm just bad at understanding some sound arguments here, or the arguments are elaborate self-delusions of people who are smarter and better at arguments than me. In any case, I feel epistemic learned helplessness on some of these most basic questions in ARC's agenda.

What is your opinion on the Low Probability Estimation paper published this year at ICLR?

I don't have a background in the field, but it seems like they were able to get some results, that indicate the approach is able to extract some results. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2410.13211

It's a nice paper, and I'm glad they did the research, but importantly, the paper reports a negative result about our agenda. The main result is that the method inspired by our ideas under-performs the baseline. Of course, these are just the first experiments, work is ongoing, this is not conclusive negative evidence for anything. But the paper certainly shouldn't be counted as positive evidence for ARC's ideas.

Thanks for the clarification! Not in the field and wasn't sure I understood the meaning of the results correctsly.

I was very skeptical from the beginning, for largely similar reasons I expressed in my posts. But first I told myself that I should stay a little longer.

IME, in the majority of cases, when I strongly felt like quitting but was also inclined to justify "staying just a little bit longer because XYZ", and listened to my justifications, staying turned out to be the wrong decision.

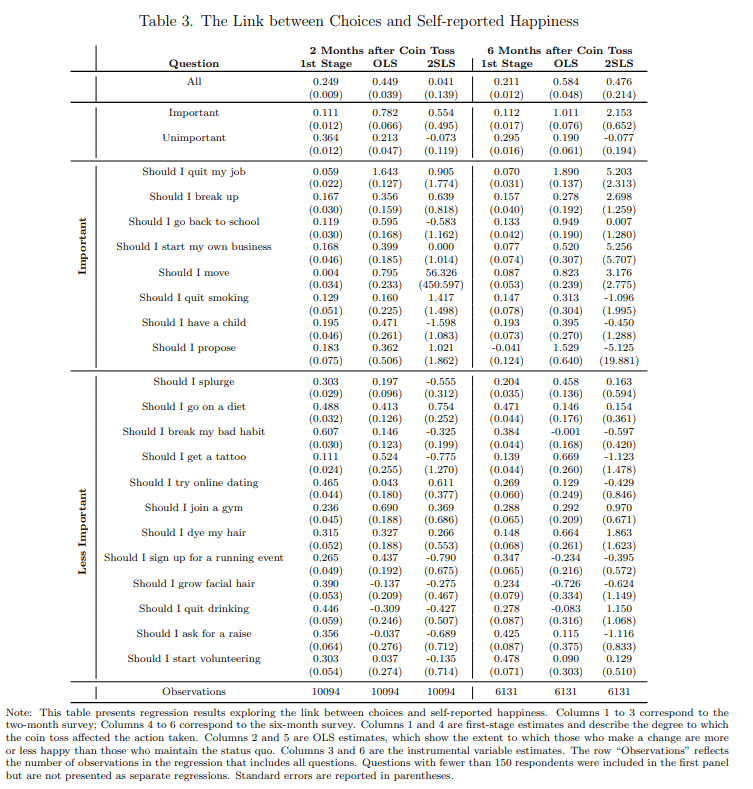

Relevant classic paper from Steven Levitt. Abstract [emphasis mine]:

Little is known about whether people make good choices when facing important decisions. This paper reports on a large-scale randomized field experiment in which research subjects having difficulty making a decision flipped a coin to help determine their choice. For important decisions (e.g. quitting a job or ending a relationship), those who make a change (regardless of the outcome of the coin toss) report being substantially happier two months and six months later. This correlation, however, need not reflect a causal impact. To assess causality, I use the outcome of a coin toss. Individuals who are told by the coin toss to make a change are much more likely to make a change and are happier six months later than those who were told by the coin to maintain the status quo. The results of this paper suggest that people may be excessively cautious when facing life-changing choices.

Pretty much the whole causal estimate comes down to the influence of happiness 6 months after quitting a job or breaking up. Almost everything else is swamped with noise. The only individual question with a consistent causal effect larger than the standard error was "should I break my bad habit?", and doing so made people unhappier. Even for those factors, there's a lot of biases in this self-report data, which the authors noted and tried to address. I'm just not sure what we can really learn from this, even though it is a fun study.

How exactly are you measuring coding ability? What are the ways you've tried to upskill, and what are common failure modes? Can you describe your workflow at a high-level, or share a recording? Are you referring to competence at real world engineering tasks, or performance on screening tests?

There's a chrome extension which lets you download leetcode questions as jupyter notebooks: https://github.com/k-erdem/offlineleet. After working on a problem, you can make a markdown cell with notes and convert it into flashcards for regular review: https://github.com/callummcdougall/jupyter-to-anki.

I would suggest scheduling calls with friends for practice sessions so that they can give you personalized feedback about what you need to work on.

Someone should do the obvious experiments and replications.

Ryan Greenblatt recently posted three technical blog posts reporting on interesting experimental results. One of them demonstrated that recent LLMs can make use of filler tokens to improve their performance; another attempted to measure the time horizon of LLMs not using CoT; and the third demonstrated recent LLMs' ability to do 2-hop and 3-hop reasoning.

I think all three of these experiments led to interesting results and improved our understanding of LLM capabilities in an important safety-relevant area (reasoning without visible traces), and I'm very happy Ryan did them.

I also think all three experiments look pretty obvious in hindsight. LLMs not being able to use filler tokens and having trouble with 2-hop reasoning were both famous results that already lived in my head as important pieces of information about what LLMs can do without visible reasoning traces. As far as I can tell, Ryan's two posts simply try to replicate these two famous observations on more recent LLMs. The post on measuring no CoT time horizon is not a replication, but also doesn't feel like a ground-breaking idea once the concept of increasing time horizons is already known.

My understanding is that the technical execution of these experiments wasn't especially difficult either, in particular they didn't require any specific machine learning expertise. (I might be wrong here, and I wonder how many hours Ryan spent on these experiments. I also wonder about the compute budget of these experiments, I don't have a great estimate of that.)

I think it's not good that these experiments were only run now, and that they needed to run by Ryan, one of the leading AI safety researchers. Possibly I'm underestimating the difficulty of coming up with these experiments and running them, but I think ideally these should have been done by a MATS scholar, or ideally by an eager beginner on a career transitioning grant who wants to demonstrate their abilities so they can get into MATS later.

Before accepting my current job, I was thinking about returning to Hungary and starting a small org with some old friends who have more coding experience, living on Eastern European salaries, and just churning out one simple experiment after another. One of the primary things I hoped to do with this org was to go through famous old results and try to replicate them. I hope we would have done the filler tokens and 2-hop reasoning replications too. I also had many half-baked ideas of running new simple experiments investigating ideas related to other famous results (in the way the no-CoT time horizon experiment is one possible interesting thing to investigate related to rising time horizons).

I eventually ended up doing something else, and I think my current job is probably a more important thing for me to do than trying to run the simple experiments org. But if someone is more excited about technical research than me, I think they should seriously consider doing this. I think funding could probably be found, and there are many new people who want to get into AI safety research; I think one could turn these resources into churning out a lot of replications and variations on old research, and produce interesting results. (And it could be a valuable learning experience for the AI safety beginners involved in doing the work.)

FWIW, Daniel Kokotajlo has commented in the past:

> If there was an org devoted to attempting to replicate important papers relevant to AI safety, I'd probably donate at least $100k to it this year, fwiw, and perhaps more on subsequent years depending on situation. Seems like an important institution to have. (This is not a promise ofc, I'd want to make sure the people knew what they were doing etc., but yeah)

but I think ideally these should have been done by a MATS scholar, or ideally by an eager beginner on a career transitioning grant who wants to demonstrate their abilities so they can get into MATS later.

A problem here is that, I believe, this is on the face of it not quite aligned with MATS scholars' career incentives, as replicating existing research does not feel like projects that would really advance their prospects of getting hired. At least when I was involved in hiring, I would not have counted this as strong evidence or training for strong research skills (sorry for being part of the problem). On the other hand, it is totally plausible to incorporate replication of existing research as part of a larger research program investigating related issues (i.e. Ryan's experiment about time horizon without COTs could fit well within a larger work investigating time horizons in general).

This may look different for the "eager beginners", or something like the AI safety camp could be a good venue for pure replications.

Interesting. My guess would have been the opposite. Ryan's three posts all received around 150 karmas and were generally well-received, I think a post like this would be considered 90th percentile success for a MATS project. But admittedly, I'm not very calibrated about current MATS projects. It's also possible that Ryan has good enough intuitions to have picked two replications that are likely to yield interesting results, while a less skillfully chosen replication would be more likely to just show "yep, the phenomenon observed in the old paper is still true". That would be less successful but I don't know how it would compare in terms of prestige to the usual MATS projects. (My wild guess is that it would still be around median, but I really don't know.)

(adding my takes in case they are useful for MATS fellows deciding what to do) I have seen many MATS projects via attending the MATS symposiums, but am relying on my memory of them. I would probably consider Ryan's posts to each be like 60-70th percentile MATS project. But I expect that a strong MATS scholar could do 2-5 mini projects like this during the duration of MATS.

I think I disagree—doing research like this (especially several such projects) is really helpful for getting hired!

Before accepting my current job, I was thinking about returning to Hungary and starting a small org with some old friends who have more coding experience, living on Eastern European salaries, and just churning out one simple experiment after another.

I think such an org should focus on automating simple safety research and paper replications with coding agents (e.g. Claude Code). My guess is that the models aren't capable enough yet to autonomously do Ryan's experiments but they may be in a generation or two, and working on this early seems valuable.

The Coefficient technical grant-making team should pitch some people on doing this and just Make It Happen (although I'm obviously ignorant of their other priorities).

I commented something similar about a month ago. Writing up a funding proposal took longer than expected but we are going to send it out in the next few days. Unless something bad happens, the fiscal sponsor will be the University of Chicago which will enable us to do some pretty cool things!

If anyone has time to look at the proposal before we send it out or wants to be involved, they can send me a dm or email (zroe@uchicago.edu).

Do you have suggestions for other particularly approachable but potentially high impact replications or quick research sprints?

Redwood has project proposals, but these seem higher effort than what you're suggesting and more challenging for a beginner

https://blog.redwoodresearch.org/p/recent-redwood-research-project-proposals