I think most things mentioned in 1.4 ("Algorithmic changes that are not really quantifiable as efficiency") belong to 1.1 (algorithmic efficiency progress) because they can actually be quantified as efficiency improvements, namely SFT, RLHF, RLVR. These have strongly increased capabilities, as measured by benchmarks, compared to GPT-3-style prompt engineering of the underlying base model. So a much smaller model with these improvements can get to the performance of a larger base model without them.

Especially the invention and subsequent improvement of RLVR has made things possible (advanced math, programming, agentic tool-use, answering of any questions that require a non-trivial amount of reasoning) that were far out of reach for older frontier models like GPT-3/GPT-4, which didn't have any robust reasoning ability, apart from the very brittle (hallucination-prone) "think step by step" trick.

I would also include improvements from synthetic training data as an algorithmic improvement, not a data-related improvement, because better synthetic training data is created by better algorithms. E.g. AlphaGo Zero would clearly count as pure algorithmic improvement, because the synthetic data generated during self play is itself the output of an improved algorithm. By the way, more recent forms of RLVR also include self play, which hasn't been appreciated enough in my opinion. (Self play can be classified as a weak form of RSI that is distinct from classical RSI as an AI that does AI research.)

Even in forms of RLVR which rely on human-written training tasks without self play, data-related improvement is not independent of algorithmic progress from RLVR: Because the data would be useless without first inventing RLVR. So it is difficult (as Gundlach apparently tries) to say which of them caused "more" of the progress they caused in combination.

Regarding distillation:

I propose that model distillation is the main explanation for the Gundlach et al. 2025a claim that inference compute has been dropping 3×/year, holding quality fixed. As the biggest and best models get ever bigger and better, the tiny distilled models get better too, thus surpassing quality thresholds that previously required a bigger model.

I think model distillation would not cause such a large and ongoing improvement in inference efficiency. When you first invent model distillation (a purely algorithmic type of progress), there is indeed a large one-time efficiency improvement, because a small model created from distillation is suddenly much better than another small model created without distillation. However, subsequently to that, there is no such improvement anymore, i.e. the relative difference between Gemini 2.5 Flash and Gemini 3 Flash (distilled models) presumably matches approximately the relative difference between Gemini 2.5 Pro and Gemini 3 Pro. So you now have 0x further improvement from model distillation, as the improvement in the smaller models matches the improvement in the larger ones. Unless the distillation method itself improved -- but this would again count as progress caused by an algorithmic efficiency improvement.

Thanks for the feedback!

I would also include improvements from synthetic training data as an algorithmic improvement, not a data-related improvement, because better synthetic training data is created by better algorithms…

I have now changed the text in a few places to better clarify how I am defining the scope of §1.1.

I feel like you’re maybe reading in some subtext, where you think I’m trying to downplay the things outside §1.1, and suggest that they don’t really count, or something? If so, that’s not what I meant to suggest, and it’s not how I feel in my heart. I’m open to rewording more, if you have suggestions.

I think most things mentioned in 1.4 ("Algorithmic changes that are not really quantifiable as efficiency") belong to 1.1 (algorithmic efficiency progress) because they can actually be quantified as efficiency improvements, namely SFT, RLHF, RLVR. These have strongly increased capabilities, as measured by benchmarks, compared to GPT-3-style prompt engineering of the underlying base model. So a much smaller model with these improvements can get to the performance of a larger base model without them.

In the context of this post, I’m mainly interested in: (1) are the things in §1.4 relevant to the Epoch claim of exponential algorithmic improvements? and (2) are the things in §1.4 relevant to the Dario claim of exponential algorithmic improvements? It seems to me that the answer in both cases is “no”.

(1) In the Epoch case, I believe they quantified performance by perplexity not benchmarks.

(2) In the Dario case, I mean, I keep reading and re-reading the exact wording of the excerpt where he talks about “compute multipliers”. And it just really doesn’t sound to me like he is referring to SFT, RLHF, or RLVR in that excerpt (nor anything else in §1.4). Admittedly, his wording is a bit vague and confusing (to me). I’m open to discussion.

I think model distillation would not cause such a large and ongoing improvement in inference efficiency.

Pick a fixed model size, let’s say N=50B parameters. My current belief is that: if you straightforwardly distill Claude Opus 3.5 into an N-parameter model, then you wind up with a worse model, than if you straightforwardly distill Claude Opus 4.5 into an N-parameter model.

Are you disagreeing with that?

If you agree, then it would follow that (for example) maybe:

- Alice can distill Opus 3.5 into a 100B-parameter model

- Bob can distill Opus 4.5 into a 40B-parameter model

- …And the two models may have the same benchmarks

(because Bob’s better starting point is making up for his more aggressive distillation). Thus we would see ever-falling inference costs at any given level of benchmarks. See what I mean?

Okay, distillation to a fixed-size model, as you describe here, does seem like it measures largely data-related improvements, so this seems consistent with Gundlach. Except perhaps for cases where the "distillation" includes training on synthetic reasoning traces and we count these as algorithmic rather than data-related. Though I don't know enough about how distillation works and whether that would count as distillation to comment on that.

If Epoch did indeed measure algorithmic progress with perplexity only, then that's no longer justified since models have shifted more toward improving reasoning rather than scaling pre-training, and only pre-training reduces perplexity. To measure algorithmic progress now, one would have to measure training/inference compute vs benchmarks, since benchmarks are the only measurable close correlate of practical real-world performance. But this would again include data-related progress as well.

Dario did indeed with your excerpt (from the section "shifting the curve") not mean RLVR, because he talks about RLVR separately in the next section under the title "shifting the paradigm". I would still say that much of this paradigm shift counts as algorithmic progress, though because it made new forms of training data accessible (RL environments), algorithmic and data-related progress can no longer be clearly distinguished here.

I believe open data pretty strongly contradicts your claims

System efficiency: ~2x, not ~20x

§1.2 estimates "up to 20x" from system optimizations (quantization, parallelization, FlashAttention, etc.). But model FLOPs Utilization, the fraction of peak hardware FLOPs that large training runs actually achieve, has barely changed. Here are the most legible training run flops efficiencies:

- Megatron-LM 2019: 30% on a single V100

- PaLM 2022: 46% on 6K TPU v4s

- Llama 3.1 2024: 38-43% on 16K H100s

- MegaScale 2024: 55% on 12K GPUs

- Llama 4 2025: 39% BF16-equivalent on 32K H100s

That's less than 2x variation over 6 years. Most optimization work at scale is treading water against communication overhead as clusters grow larger, not increasing training compute per chip. Also, individual optimizations like FlashAttention's 3x attention speedup are additive rather than multiplicative, and many other optimizations only apply to inference, not training.

The Gundlach paper tests 6 innovations. The field has produced 40+.

§1.1 relies on Gundlach et al. (2025b), which ablated six things, SwiGLU, RoPE, cosine decay, pre-RMSNorm, pre-LayerNorm, and AdamW. The most algorithmically advanced models with published methodology are DeepSeek-V3, DeepSeek-R1, and Kimi K2, and here's a list of algorithms they used that Gundlach didn't test:

Architecture:

- Fine-grained MoE: 256 routed + 1 shared expert, 8 active per token

- Ultra-sparse MoE: scaling to 384 experts at fixed active params

- No token-dropping in MoE (enabled by better balancing)

- Multi-Head Latent Attention (MLA): low-rank KV compression

- Sigmoid gating with top-K normalization replacing softmax

- Auxiliary-loss-free load balancing via learned bias terms

- YaRN context extension (4K→128K in 2000 fine-tuning steps)

Training methodology:

- Multi-token prediction with sequential causal chain

- MuonClip optimizer: Muon + QK-Clip for stable training (zero loss spikes over 15.5T tokens)

- Fill-in-Middle pretraining (10% of data in PSM order)

- LLM-based data rephrasing for knowledge and math (outperforms naive multi-epoch)

- Multi-phase learning rate schedule with annealing stages

Post-training:

- GRPO: RL without a critic model

- Four-stage pipeline: cold-start SFT → reasoning RL → rejection sampling SFT → all-scenario RL

- Rule-based rewards avoiding neural reward model hacking

Of these, Muon alone is ~2x, which is on par with AdamW vs SGD.

HellaSwag: an example 10x+ compute multiplier, without distillation or synthetic data

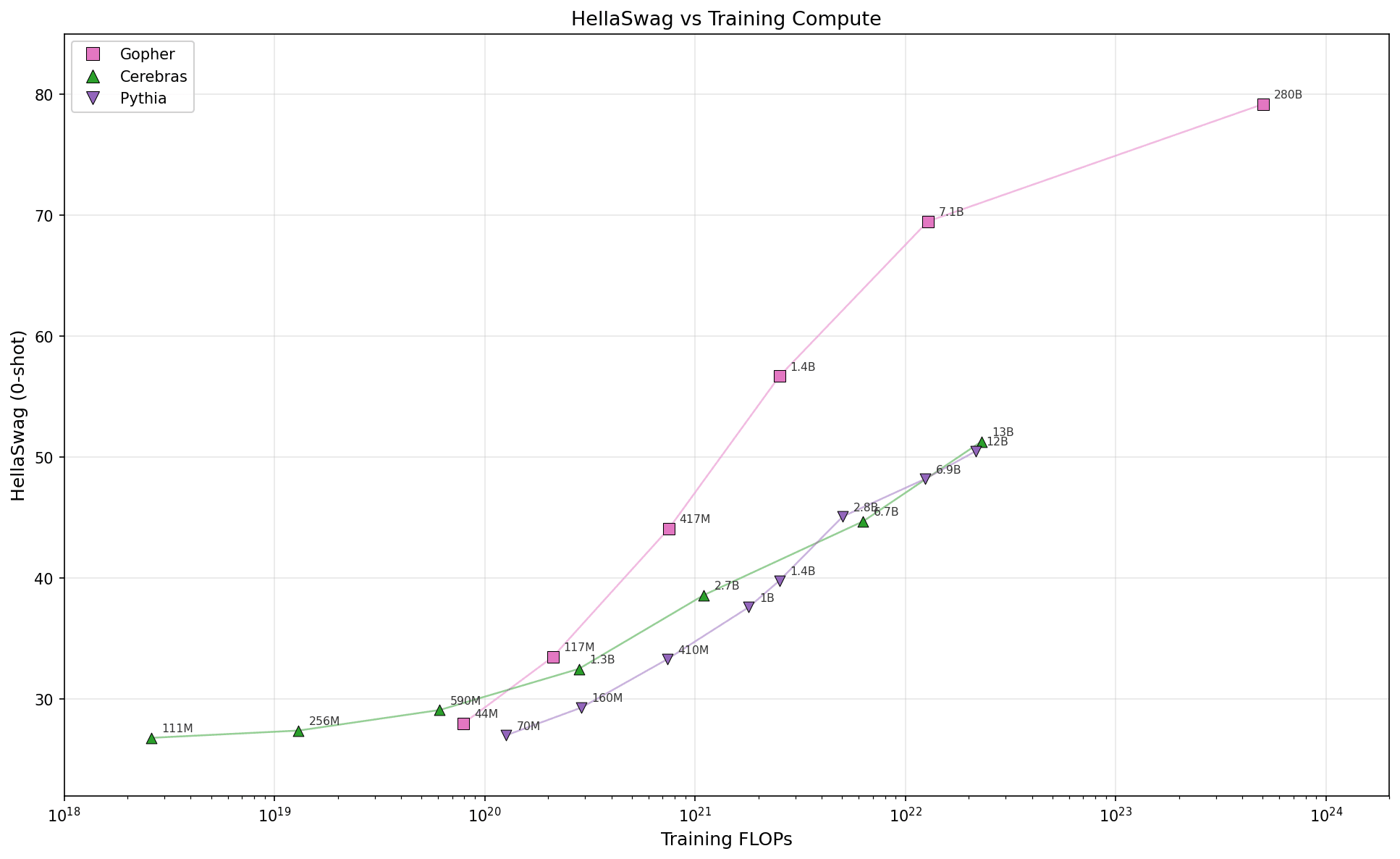

Three model families, each trained at a fixed recipe across multiple sizes: Gopher (2021), Cerebras-GPT (2023, Chinchilla-optimal), and Pythia (2023), and they didn't use any distillation, targeted data similar to benchmarks, or data contractors. Gopher reaches the same HellaSwag score as Cerebras-GPT or Pythia with roughly 10x less compute, and while using Kaplan parameter scaling. There was pretty much no legible algorithm in the paper that obviously caused this difference.

There's lots more evidence, and many models such as Qwen or R1 got significantly higher compute multipliers, but as you note, some fraction of that is from distillation or data labelling.

Note: Claude 4.6 wrote most of this, with a huge number of revisions and fixes from me, it wasn't really an uplift compared to only using Claude to make the list and the plot.

I just want to make it clear that both are paper and Epoch’s paper addresses innovations that occur from 2012-2023 (and only the first half of 2023). We are aware of MLA, muon optimizer, long context unlocks, and RL, and think they are important contributors. However, all these innovations are explicitly outside of the scope of our current paper which seeks to account for Epoch's estimates in that time period.

Thanks for your feedback; I incorporated some of it in my rewrite (it’s now version 2). In particular, I appreciate the data showing FLOP utilization staying (roughly) constant, and the idea that there’s a red-queen race against communication overhead etc. And I added some of those examples from DeepSeek & Kimi in the appropriate sections. Thanks!

…But I do want to push back on your suggestion that your HellaSwag plot implies what you think it implies.

- The hypothesis that Gopher is better than the other two mainly because of better training data seems like a totally viable hypothesis to me. For example, Gopher trained on 20× more books, presumably due to Google’s mountain of proprietary scanned book data. (Gopher trained on MassiveText which has 4M books adding up to 2.1TB of text (27% sampling proportion), while the other two used The Pile which has 100.96 GiB of book text.) Books are probably very important, but the datasets differ in other ways too. MassiveText has 2.7TB of news (10% sampling proportion), presumably from decades of Google News, whereas The Pile seems to have only whatever news articles showed up in the general web scrape. Etc.

- The hypothesis that Gopher is better mainly because DeepMind has more secret sauce or better-tuned hyperparameters or whatever seems also like a totally viable hypothesis, as far as I know.

So I don’t think this is very strong evidence either way, and indeed if anything I would suggest that it’s pushing a bit in the direction of data over algorithms, especially given that Gopher was earlier. Right? Sorry if I’m misunderstanding.

Thanks!! Quick question while I think over the rest:

What data are you plotting? Where exactly did you get it (i.e., what references)?

And why is the 2021 one better than the 2023 ones? Normally we would expect the other way around, right? Does DeepMind have so much secret sauce that it’s worth more than 2 years of public knowledge? Or are the other two groups making rookie mistakes? Or am I misunderstanding the plot?

Why is Gopher better than Pythia or Cerebras? Mostly no comment, but I think Pythia and Cerebras weren't making any super simple obvious mistake but were behind 2021-era DeepMind.

I agree with a lot of this post, but one other motivation (at least for me) is that checking how much algorithmic progress exists/comes from compute is that it's relevant to predictions around recursive self-improvement/software intelligence explosion without increasing compute, assuming you have AIs that can fully automate AI research, and more generally informs takeoff speeds, and I take the Gundleach et al paper as evidence that pure software improvements are more likely to cap out at relatively modest impacts than creating a self-sustaining feedback loop of progress, slowing down AI takeoff by quite a bit until we massively scale up compute for AGIs.

(The evidence value is reduced but not eliminated by the fact that they tested it on LLMs).

For running out of optimizations, there is another factor. And that is that some amount of re-optimization is needed each time you change hardware. Consequentially it is really hard to separate hardware progress (the new NVIDIA chips are better) from optimization of the software that runs on them (Because they have new features, the use of which is an optimization)

I am low confidence on this, but I'd be pretty skeptical of 10x from optimizations. FlashAttention is a 3x or so for attention itself (it's less of a big deal on older hardware too) but the rest of a transformer is fairly efficient large matmuls. In general modern GPUs have lower utilization on each passing generation, and GPT-2 was trained on TPUs which famously have much higher utilization (~95% vs ~60% for a pure matmul). Possibly the whole thing was just done so inefficiently you could have gotten a 10x though.

That’s helpful, thanks! The new version 2 has a rewritten optimization section, hope it’s better now.

Thanks for this really helpful nuance, where distinguishing types of algorithmic improvement seems really important for forecasting out when and how the trends will deflect, how R&D inputs and Wright's Law ish effects apply to each factor, and how recursive 'self' improvement might play out.

Dario’s been working primarily on Transformer-based LLMs for at least 7 years. I flat out do not believe that those kinds of “optimizations” can make the same calculations run

It's a nit, but he was saying that he estimates the rate now to be 4x, not that it's been 4x the whole time. So he's not claiming it should be 16k times more economical now.

Fair enough, I reworded slightly. (Although I’d be pretty surprised if LLM algorithmic progress were way faster today than in, say, 2020, given that there was presumably much more low-hanging fruit in 2020.)

This might be some sort of crux between you and him, where he might point to growth in researcher focus/headcount as well as perhaps some uplift from AI by now. (I might endorse the first of those a bit, and probably not the second, thought it's conceptually reasonable and not out of the question.)

FWIW, I would not be surprised if LLM algorithmic progress was considerably faster today than in 2020. Per my recent post, I think catch-up algorithmic progress is very fast today, and it seems like it wasn't so fast a few years ago.

I believe this article would benefit from some investigation of the NanoGPT speedrun: a challenge, running since May 2024, of training GPT-2 Small 124M on a certain dataset to a certain loss. As a starting point, you could check my comment on the topic from last month and reproduce findings by T. Besiroglu and yours truly.

In order not to duplicate the comment but still add something to what I have written on the topic, let me put a three-paragraph summary of the trend line analysis below, noting that the progression in calendar time (as opposed to record number) is very uneven:

Gemini's summary of the QLR analysis of the speedrun progression (written a month ago)

- The "Flex" Point: The QLR test points to Record 12 as the most significant structural break. This coincides with the transition from dense causal attention to FlexAttention, which enabled much faster training by optimizing the attention mechanism.

- Diminishing Returns: The slope is steeper in the first phase (-0.80) than in the second (-0.53). This indicates that early "low-hanging fruit" optimizations (like introducing the Muon optimizer and standardizing architecture) provided a faster rate of improvement per record than the later, more incremental system and hyperparameter tweaks.

- Stability: After the "saturation" phase begins around Record 12–15, the progress remains remarkably consistent on a log-log scale, following a new, slightly shallower power law as contributors fought for smaller second-by-second gains.

I am quite uninformed, but when I read about compute multipliers I considered it to obviously include data-related improvements. To quip, FineWeb-Edu was algorithmically filtered, it obviously wasn't manually curated. As an evidence that it is not just my misunderstanding, I quote Dean W. Ball (my point is that it may well be my misunderstanding, but then such misunderstanding is common):

... Amodei describes this as a "compute multiplier": ... These gains come from all sorts of places: ... improvements to training datasets that allow the model to learn more quickly ...

Well I don’t think either Epoch and Dario were talking about data improvements (Epoch because they used perplexity not benchmarks, and perplexity on a fixed corpus is only slightly helped by training data improvements; and Dario based on the wording he used, see §2.2 excerpt).

If Epoch and Dario are making claims that are crazy (6-8 month halving time excluding the data category), and lots of people misunderstood those claims as asserting something directionally less crazy (6-8 month halving time including the data category) … umm, I guess that’s a good thing for public understanding of LLMs, and I should be happy about it?

But it still matters for other reasons. E.g. I think people cite and use the specific exponential halving times proposed by Dario and Epoch, in the context of forecasts and such (e.g. maybe AI-2027?). If the specific Dario & Epoch numbers are based on bad / confused / confusing methodology, then those specific numbers should not be used. We would need a different method—and no comment on whether that method would give a number that’s higher, or lower, or the same by coincidence.

quantization

Quantization advances actually go hand-in-hand with hardware development, check the columns on the right in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nvidia_DGX#Accelerators (a GPU from 2018 is pretty useless for inferencing an 8-bit quant)

UPD: Actually, this point was already been made in comments in other wording yesterday!

KV cache

Seems out of place in the list: as noted by Nostalgebraist, it was already implemented in the very first transformer in 2017

I know very little about this topic, but I was under the impression that there was more to it than “KV cache: yes or no?”, and I was trying to refer to that whole category of possible improvements. E.g. here’s a paper on “KV cache compression”.

Possibly better to have a fresh new post, and point each post to the other, rather than updating in place? (You could still keep the changelog, which is polite and helpful for your readers.) In particular, I only saw this revision by luck.

(Heavily revised on Feb. 9, 2026—see changelog at the bottom.)

There’s a lot of talk about “algorithmic progress” in LLMs, especially in the context of exponentially-improving algorithmic efficiency. For example:

It’s nice to see three independent sources reach almost exactly the same conclusion—halving times of 8 months, 6 months, and 7½ months respectively. Surely a sign that the conclusion is solid!

…Haha, just kidding! I’ll argue that these three bullet points are hiding three totally different stories. The first two bullets are about training efficiency, and I’ll argue that both are pretty misleading (each for a different reason!). The third is about inference efficiency, which I think is right, and mostly explained by distillation of ever-better frontier models into their “mini” cousins.

Tl;dr / outline

Status of this post

I wrote this very quickly, on a topic where I am not remotely an expert. I’m hoping for feedback and opinions!

1. The big picture of LLM algorithmic progress, as I understand it right now

1.1 Stereotypical learning algorithm improvements: there’s the Transformer itself, plus another maybe 10× since 2018

I’m defining this category as changes related to the core learning algorithm itself—neural architecture changes, SGD vs AdamW, etc.—apart from a couple categories that get their own sections below.

Here’s my current impression (any uncited claims probably come from @Hans Gundlach et al. 2025b “On the origin of algorithmic progress in AI”):

1.2 Innovations that unlock long context windows

If I understand correctly, the original Transformer could be run in principle with an arbitrarily long context window. But beyond a certain (low) length, the memory demands would catastrophically reduce FLOP utilization to ≈0. Then a 2019 advance (“MQA”) made longer context windows practical, but performed worse than the original (“MHA”) Transformer (holding context window fixed). Then further advances (MQA → GQA → MLA) clawed back most of that performance degradation, while keeping the low memory footprint.

Also in the “unlocking long context windows” category is things like YaRN, a trick to get good long-context performance out of mostly-short-context training data, by basically extrapolating a short-context trained attention layer into a good initialization for a longer-context trained attention layer. And then you need much less actual training, because the initial state is already so good.

Anyway, this category of innovations seems very important. Exactly how important? I don’t know! I can’t immediately find a reference that quantifies it in a legible-to-me way.

1.3 “Optimizations”: Lots of work, but there’s always a ceiling

This category is stuff that wouldn’t show up in a FLOP metric, but it’s equally important for cost. It includes everything specific to a particular hardware configuration and training setup—details about quantization, parallelization, FlashAttention, other CUDA black magic, and so on. I’ll also thro system-level optimizations like speculative decoding into this category.

My impression is: it takes a lot of work to keep FLOP utilization high as the chips grow ever faster and the parallelization grows ever more aggressive. (Per the Red Queen: “It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”) So if we’re trying to compute how “algorithmic efficiency” changes over time, I think we wouldn’t see much effect from this category. From the outside, it would look like: some company’s FLOP utilization (actual FLOP/s achieved compared to “peak FLOP/s” according to the GPU spec sheet) was X% last year, and it’s still around X% today, but they’re training bigger models. From that outside perspective, we would summarize the situation by saying that the company’s “algorithmic progress” is zero while their “compute growth” is high. But that summary would be hiding a lot of “optimization”-type innovation under the hood.

Alternatively, instead of comparing year-on-year as configurations change, we might hold fixed a hardware configuration and training setup, and ask how efficiency might change over time due to these kinds of “optimizations”. I think this multiplier could be quite big (say, 20×) if the baseline is a sufficiently early slapdash implementation. I think the multiplier would be smaller (but still substantial—say, 3×) even many months later, after some of the low-hanging fruit is gone, but a long tail of smaller “optimizations” still remains. For example, the original FlashAttention alone apparently sped up certain training setups by 3× wall-clock time (but other setups by less). Much later on, as a random example, the “nanoGPT speedrun” got a 9% wall-clock speed boost in 2024 by simply incrementing the PyTorch version.

What I don’t believe is that “optimizations” can contribute to an ever-growing exponential, where it’s 10× after two years, 100× after four years, 1000× after six years, etc. These kinds of optimizations have a ceiling, where you’re doing the best you can with the training approach and hardware configuration you’ve got. GPU utilization cannot exceed 100%. Quantization can’t go below 1 bit. Etc.

1.4 Data-related improvements

As discussed in “Most Algorithmic Progress is Data Progress” by Beren Millidge (@beren), a lot of LLM improvement has come from more and/or better training data,[4] including:

What are the impacts of these data-related improvements? Are they relevant to those exponentials at the top? My current take is:

1.5 Algorithmic changes that are not really quantifiable as “efficiency”

If we put aside the “3×/year” and related quotes at the top, and take a broader view of what LLM algorithmic progress can look like, then of course we find many more items. These include:

2. Explaining away the two training-efficiency exponential claims

At the top, I cited Epoch AI and Dario Amodei as claiming that algorithmic improvements constitute a rapid exponential that’s been going on for years. I don’t currently believe either of them. Here’s why.

2.1 The Epoch “8-month halving time” claim seems to be mostly a weird artifact of their methodology

(The Epoch AI claim in question is at blog, paper, and my response here is entirely based on Gundlach et al. 2025b.)

Some algorithmic changes matter more and more as the model scale gets bigger. Specifically, there were two such changes: the switch from LSTMs to Transformers, and Chinchilla-optimal training.

For example, let’s suppose that the Transformer is N× more efficient than LSTMs with 2018-scale LLMs, and 10N× more efficient than LSTMs with 2025-scale LLMs.

Now let’s put aside everything else, and imagine a world where we switch from LSTMs to Transformers in 2018, and then scale up the transformers from 2018 to 2025 with no additional algorithmic change at all. In the Epoch methodology, they would say that we got an “extra” 10× algorithmic improvement (50%/year!) in the 2018-2025 period, because we’re kinda milking ever more advantage from the one-time LSTM-to-Transformer switch.

OK, but … that’s super confusing! Right? By assumption, the algorithms weren’t actually getting better during that 2018-2025 period, at all!

Anyway, the important point is: the actual Epoch analysis seems to be fully compatible with the claims I made in §1.1 above.

(The only puzzle here is that Gundlach et al. 2025b claims to perfectly account for the Epoch “improvement” … but the things omitted by Gundlach et al. (especially the “unlockers of long context windows” in §1.2) should account for some of the Epoch “improvement” as well, right? So I figure that Gundlach et al. must have some minor inaccuracies that account for the balance.)

2.2 The Dario “4x/year” claim is I think largely confused double-counting?

I quoted Dario Amodei 2025 at the top. Here’s a longer version of that quote:

At first, I found this quote baffling. Dario has been working primarily on Transformer-based LLMs for at least 7 years. So I guess he’s saying that we’ve improved by 47= 16,000× just from algorithms? But, c’mon, that’s nuts! Right?

(Some commenters suggested that maybe Dario’s belief is that it’s 4×/year today, but lower in the past. My response: maybe that’s true to some small extent, but in context, I think this is sanewashing, and that Dario’s belief has to be at least ≳3000× in the last seven years.[6] And I still think that’s nuts.)

So what the heck is Dario talking about??

…But I think I got it now. So here’s my current take—the only way I can get everything to fit together and make sense:

Overall, I remain confused, and I think Dario is probably doing a lot of this double-counting stuff, and/or describing things in a confusing way.

[Boy, I sure feel weird about lecturing Dario Amodei on the big picture of LLM training! He knows more about LLM training than almost anyone on Earth, and I have (checks notes) no LLM training experience whatsoever. So if anyone has a different proposal for how to make sense of Dario’s quote above, I’m all ears!]

3. Sanity-check: nanochat

There were seven years between GPT-2 (trained in early 2019) and the new nanochat, which matches GPT-2 performance on the “CORE” metric (“a diverse set of reasoning and knowledge tasks from the DCLM benchmark suite”).

Remarkably, Karpathy says here that nanochat training costs $73 (“3 hours on a single 8XH100 node”), whereas “GPT-2 was trained by OpenAI on 32 TPU v3 chips for 168 hours (7 days), with $8/hour/TPUv3 back then, for a total cost of approx. $43K”.

So that would be a factor of 600 in 7 years, i.e. a halving time of 9 months. Is that consistent with my story in §1? I think so! For example, it might be something like:

For that last one: GPT-2 used “webtext”, which was generated by scraping URLs linked from Reddit. By contrast, nanochat trains on “fineweb-EDU”, a dataset of educational materials crafted and curated with incomparably more effort and care. Remember, we’re comparing nanochat to GPT-2 on “reasoning and knowledge tasks”, not perplexity; I would be shocked if this better data was not playing a major role.

So anyway, my take in §1 seems at least plausibly consistent with the nanochat thing, AFAICT at a glance. To be clear, I didn’t check things in detail or scrutinize it very hard. If anyone wants to really check, you could just download nanochat and have at it!

4. Optional bonus section: why does this matter?

Well for 99% of the people reading this post, this topic matters to you because you’re trying to forecast future LLM progress. But that’s not my interest, so I won’t talk about it. I’ll leave that to others!

I’m actually interested in a rather different, older debate, one predating LLMs, between two schools of thought. Here’s the debate:

One school of thought (that I vaguely associate with Paul Christiano[7]) says: When people are trying to do something in ML, they very rapidly get to near the ceiling of how efficiently they can do that thing, given the available data and hardware situation (but perhaps leaving aside paradigm shifts, which are not about doing the same thing more efficiently, but rather about trying to do something different instead).

A different school of thought says: No, that’s wrong, instead when people are trying to do something in ML, there will be a very large collection of algorithmic improvements that could make it work more efficiently, and these improvements will take many thousands of person-years to discover, and they will collectively amount to orders of magnitude of efficiency difference.

So that’s a debate. The reason I care about this debate is unrelated to LLMs; rather it’s part of an in-the-weeds argument about how fast “takeoff” to superintelligence might be if we someday have a post-LLM AI paradigm shift (as I happen to expect). See Foom & Doom 1: “Brain in a box in a basement”, e.g. comment on that post by @ryan_greenblatt. I’m generally in the first school of thought, which is related to my expectation of sudden takeoff to ASI.

…OK, if that’s the debate, then what lesson do we take away from this LLM case-study? My answer: If I’m right (a big “if”!), then (I would argue) the history of LLMs seems to support the first school of thought more than the second.

To be clear, I don’t think this kind of analogizing is terribly strong evidence either way; and note also that there are other case-studies like this ImageNet analysis that might or might not paint a different picture, I didn’t check.

In fact, there are two key disanalogies between LLMs versus the future AI paradigm I’m expecting (see Foom & Doom 1), and they make my case for sudden takeoff (conditional on that paradigm shift) even stronger: the future paradigm I’m expecting would (1) not rely on training data for its capabilities (unlike LLMs), making §1.4 basically moot; and (2) require very little compute to get from random initialization to AGI (if efficiently implemented), which would allow for much more rapid iteration and testing than we’re used to from LLMs.

Thanks Hans Gundlach, Seth Herd, plex, algon, ishaan, and Alex Fogelson for critical comments on earlier drafts.

Changelog

Feb. 9, 2026: I pulled “unlockers of long context windows” into their own category (new section §1.2), ; I increased my guess of the §1.1 impact from “3-5× beyond Transformer + Chinchilla” to “10×”. I heavily reframed the discussion of “optimizations” (now §1.3), to clarify what’s getting compared to what. I added a couple more examples to the “data” category (now §1.4). Then I made various related changes to my analysis of the Dario quote, and nanochat. Thanks to the commenters for ideas and pushback!

Feb. 11, 2026: Minor typo fixes and clarifications.

Gundlach links to this paper on tokenizers, and describes it as a claim that “inefficient tokenization” can cause up to 68% performance hit. But I think that 68% number comes from comparing best practices to the extraordinarily dumb idea of building a tokenizer using English-only text and then running inference on a multilingual corpus. As for real tokenizer improvements, I think everyone’s been using BPE since before the Transformer, and different flavors of BPE seem quite similar, if I’m reading the paper right. As an example, this page benchmarks the tokenizer of the recently-released nanochat (§3) against the tokenizer used by GPT-2 in 2019, and finds 0-15% compression difference, depending on the data type. The difference probably comes from using better training data to set up the tokenizer.

FYI: They note that if you revert one of these things at a time, it has a bigger deleterious impact than if you revert the whole package at once. In other words, the “Retro Transformer” and the “Modern Transformer” were each a package of components that worked particularly well together.

For example, Karpathy here mentions the “muon optimizer … residual pathways and skip connections gated by learnable scalars, and value embeddings”. And a commenter noted that the DeepSeek-v3 paper includes: “Sigmoid gating with top-K normalization replacing softmax”, “MuonClip optimizer”, and “Multi-phase learning rate schedule with annealing stages”. None of these seem to have been studied by Gundlach et al. 2025b, unless I missed it.

This of course fits perfectly with my belief that we should think of LLMs as getting their impressive powers almost entirely via imitation learning from their training corpus.

A commenter mentions a couple more examples: “fill-in-the-middle pretraining” (used in DeepSeek v3) and LLM-based data augmentation / rephrasing (used in Kimi K2).

For example, we can just multiply Dario’s “CMs”. E.g. if “every once in a while” means “three times ever”, then we would have 1000× just from the “very large” CMs, before we even start on the “medium” and “small” ones! Anyway, I’m willing to haggle over a factor of 2 or 5 or whatever, but I think it’s sanewashing to interpret Dario’s quote as claiming less than, say, ≳3000× over 7 years.

For example, Paul Christiano 2018: “A more precise version [of] my claim: if you gave smart grad students from 1990 access to all of the non-AI technology of 2017 (esp. software tools + hardware + data) and a big budget, it would not take them long to reach nearly state of the art performance on supervised learning and RL. For example, I think it's pretty plausible that 20 good grad students could do it in 3 years if they were motivated and reasonably well managed.” (Actually, Paul is much further in the direction of the first school of thought than I am, because I defined it with a carve-out for possible hard-to-discover paradigm shifts, and he’s not even conceding that.)