Research note: A simpler AI timelines model predicts 99% AI R&D automation in ~2032

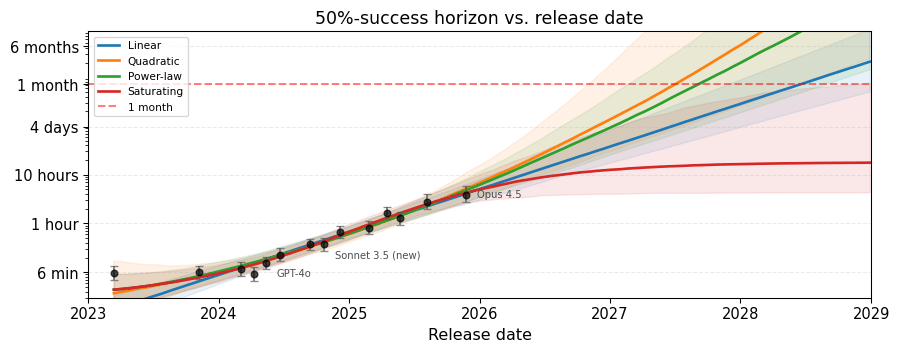

In this post, I describe a simple model for forecasting when AI will automate AI development. It is based on the AI Futures model, but more understandable and robust, and has deliberately conservative assumptions. At current rates of compute growth and algorithmic progress, this model's median prediction is >99% automation...

I don't think this is 'woke' exactly, just that Hegseth has a vision for what the military should be like which is incompatible with Anthropic applying ethical judgement. If Anthropic refuses to surveil Americans, they might push back on other things in the future, and are at especially high risk of refusing to do illegal things Hegseth wants them to. Hegseth thinks generals should be physically strong men who don't take Harvard classes; likewise, contractors should obey orders and not evaluate their ethics.