Not uncertainty, but rather high confidence of safety.

Phrased this way, it sounds all "spooky mysterious", in the way that needs a named theorem and explanation.

Phrased to be easily understood, due to the vast space and few tiny satellites, you are very unlikely to have a collision when blindly throwing darts at this dart board.

I may be maximally ignorant about what tomorrows lottery numbers will be, but I can safely predict that I will not win.

You certainly should not become more confident that 2 satellites are safe, just because you added random noise to the measurements. [...]However, giving each one a random push from its jets increases the actual variation in their paths, likely pushing them away from the previous point estimate of a collision, and thus does make them safer.

And if you add random noise, you don't get more confident. Like, if you're cruising along on what appears to be a potential collision course, and then your sensor goes bad and starts giving noisy data, you don't get more confident that you're safe. You just get more scared more slowly, in the case that you're on track to collide.

If you never had any evidence that this unlikely event is about to take place, then of course you can't magically get to the answer without evidence. Maybe you're on a collision course and jinking would make you safer. More likely though, you're just on a "close call" course, and jinking could put you on an actual collision course.

As an outsider with special knowledge, you may be rooting for the satellite to make some random motions, or to not change anything. As an engineer working on a satellite with noisy instruments, you don't have the privilege of knowing the right answer ahead of time, and you will have no way of firing the rockets only when it's helpful. If you program your satellites to move randomly, all you will accomplish is wasted fuel.

Imagine if from the inside. You're handed a revolver and forced to play Russian roulette. Your wife saw the spin and knows whether it landed on a live round and is either praying that you spin again or praying that you don't. You don't know where the live round is, and can't see or hear her. Do you ask to spin the spin the cylinder again? Would it help anything if you did?

The take away is just that if you want to predict rare events, you need evidence. Rare events do happen, if rarely, and unless you collect the evidence you'll have no choice but to be surprised if it happens to you.

With respect to the satellite problem, there is nothing problematic in the fact that when one knows nothing about the two satellites, one assigns a low probability to their collision. In agreement with this, there have been some accidental satellite collisions, but they are rare per pair of satellites.

Neither is there anything paradoxical about the fact that if you draw a small enough circle around a bullet hole, you would, before observing the hole, have assigned a probability approaching 1 to the false statement that the bullet would land outside that circle. This example is the gist of the proof of the "False Confidence Theorem".

The two satellites will either collide within the time frame of interest or they will not. Replacing "collide" with "not approach closer than some distance D", we can make a judgement about the accuracy of our tracking procedure by asking, suppose that the distance of closest approach were some value X; what probability p would we assign to the proposition that |X| < D?

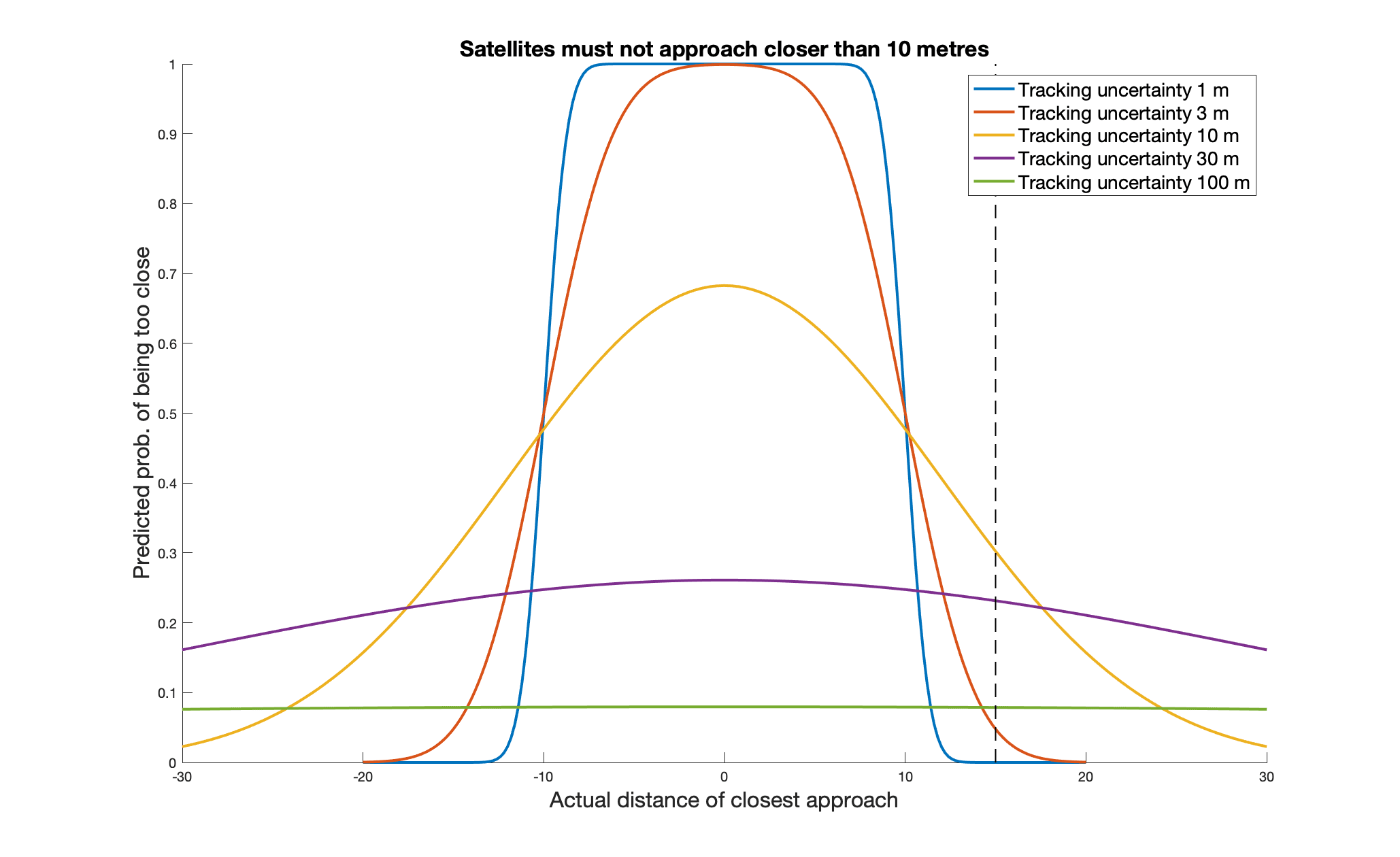

I will simplify all the details of the tracking procedure into the assumption that our estimate of closest approach is normally distributed about X with a standard deviation s (and that X is a signed quantity). Then we can plot p(D,X,s)[1] as a function of X, for various values of s.

This is what I get.

As the Litany of Gendlin says: If there will be a close approach, I want to believe there will be a close approach. If there will not be a close approach, I want to believe there will not be a close approach. The image shows that the lower the tracking uncertainty the better this ideal is achieved. Nothing is gained by discarding good information for bad.

Which was obvious already.

If you look at the curves where the distance of closest approach is 15 (the dashed line), you can see the pattern of both high and low accuracy giving low probabilities of the satellites being too close, with medium accuracy giving a higher probability. This is an obvious curiosity of no relevance to the problem of detecting possible collisions. You cannot improve a situation by refusing to look at it, only degrade your abililty to deal with it.

- ^

p(D,X,s) = normcdf( D, X, s ) – normcdf( –D, X, s ).

normcdf(A,B,C) is the cdf of the normal distribution with mean B and std. dev. C, evaluated at A.

Some further remarks.

-

The above analysis is what immediately occurred to me on reading the OP. Yet the supposed paradox, dating from 2017 (the first version of the paper cited in the OP), seems to have genuinely perplexed the aerospace community.

-

A control process cannot control a variable to better than the accuracy with which it can measure it. It is pointless to try to avoid two satellites coming within 10 metres of each other, if your tracking process cannot measure their positions better than to 100 metres (the green trace in my figure). If your tracking process cannot be improved, then you must content yourself with avoiding approaches within around 100 metres, and you will be on the equivalent of the yellow line in that figure. The great majority of the evasive actions that your system will employ will be unnecessary to avert actual collisions, which only actually happen for much closer approaches. That is just the price of having poor data.

-

I went looking on Google Scholar for the origins and descendants of this "false confidence" concept, and it's part of a whole non-Bayesian paradigm of belief as something not to be quantified by probability. This is a subject that has received little attention on LessWrong, I guess because Eliezer thinks it's a wrong turning, like e.g. religion, and wrote it off long ago as not worth taking further notice of. The most substantial allusion to it here that I've found is in footnote 1 to this posting.

Are there any members of the "belief function community" here, or "imprecise probabilists", who believe that "precise probability theory is not the only mode of uncertainty quantification"? Not scare quotes, but taken from Ryan Martin, "Which statistical hypotheses are afflicted with false confidence?". How would they respond to my suggestion that "false confidence" is not a problem and that belief-as-probability is enough to deal with satellite collision avoidance?

It is pointless to try to avoid two satellites coming within 10 metres of each other, if your tracking process cannot measure their positions better than to 100 metres (the green trace in my figure).

This seems straightforwardly false. If you can keep them from approaching within 100 metres of each other, then that necessarily also keeps them from approaching within 10 metres of each other.

It does, but very wastefully. Almost all of the avoidance manoeuvres you make will be unnecessary, and some will even cause a collision, but you will not know which ones. Further modelling (that I think would be belabouring the point to do) would allow a plot of how a decision rule for manoeuvring reduces the probability of collisions.

Let be the frequency of collisions given the tracking precision and some rule for manoeuvres. Let be the frequency of collisions without manoeuvres. Define effectiveness to be .

I would expect effectiveness to approach 1 for perfect tracking (and a sensible decision rule) and decline towards 0 as the precision gets worse.

Are you envisaging a system with 100m tracking resolution that aims to make satellites miss by exactly 10m if they appear to be on a collision course? Sure, some of those maneuvers will cause collisions. Which is why you make them all miss by 100m (or more as a safety margin) instead. This ensures, as a side effect, that they also avoid coming within 10m of each other.

The "paradox" here is that when one person says there's a 70% chance that the satellites are safe, and another says there's a 99.9% chance that they're safe, it sounds like the second person must be much more certain about what's going on up there. But in this case, the opposite is true.

When someone says "there's a 99.9% chance that the satellites won't collide," we naturally imagine that this statement is being generated by a process that looks like "I performed a high-precision measurement of the closest approach distance, my central estimate is that there won't be a collision, and the case where there is a collision is off in the wings of my measurement error such that it has a lingering 0.1% chance." But the same probability estimate can be generated by a very low-precision measurement with a central estimate that there will be a collision. The former case is cause to relax; the latter is not. Yeah, in a sense this is obvious. But it's a reminder that seeing a probability estimate isn't a substitute for real diligence.

I imagine the conversation in the control room where they're tracking the satellites and deciding whether to have one of them make a burn:

"What's the problem? 99.9% chance they're safe!"

"We're looking at 70%." [Gestures at all the equipment receiving data and plotting projected paths.] "Where did you pull 99.9% from?"

"Well, how often does a given pair of satellites collide? Pretty much never, right? Outside view, man, outside view!"

"You're fired. Get out of the room and leave this to the people who have a clue."

Right, exactly. But this isn’t only about satellite tracking. A lot of the time you don’t have the luxury of comparing the high-precision estimate to the low-precision estimate. You’re only talking to the second guy, and it’s important not to take his apparent confidence at face value. Maybe this is obvious to you, but a lot of the content on this site is about explicating common errors of logic and statistics that people might fall for. I think it’s valuable.

In the satellite tracking example, the thing to do is exactly as you say: whatever the error bars on your measurements, treat that as the effective size of the satellite. If you can only resolve positions to within 100 meters, then any approach within 100 meters counts as a “collision.”

I’m also curious about the “likelihood-based sampling distribution framework” mentioned in the cited arXiv paper. The paper claims that “this alternative interpretation is not problematic,” but it seems like its interpretation of the satellite example is substantially identical to the Bayesian interpretation. The lesson to draw from the false confidence theorem is “be careful,” not “abandon all the laws of ordinary statistics in favor of an alternative conception of uncertainty.”

Maybe this is obvious to you, but a lot of the content on this site is about explicating common errors of logic and statistics that people might fall for. I think it’s valuable.

Thank you. Maybe I over-indexed on using the satellite example, but I thought it made for a better didactic example in part because it was so obvious. I provided the other examples to point to cases where I thought the error was less clear.

The lesson to draw from the false confidence theorem is “be careful,” not “abandon all the laws of ordinary statistics in favor of an alternative conception of uncertainty.”

This is also true. Like I said (maybe not very clearly), there's more or less 2 solutions--use non-epistemtic belief to represent uncertainty, or avoid using epistemic uncertainty in probability calculations. (And you might even be able to sort of squeeze the former solution into Bayesian representation by always including "something I haven't thought of" to include some of your probability mass, which I think is something Eliezer has even suggested. I haven't thought about this part in detail.)

I didn't look for, and so was not aware of, any larger community. I found the 2 linked papers and, once I realized what was going on, recognized the apparent error in a few places. I agree that "decreasing the quality of your data should not make you more confident" is obvious when stated that way, but like with many "obvious" insights, the problem often comes in recognizing it when it comes up. I attempted to point this out to Micheal Weissman in one of the ACX threads (he did a Bayesian analysis of lab leak, similar to Rootclaim's) and he repeatedly defended arguments of this form even after I pointed out that he was getting reasonably large Bayes Factors based entirely on epistemic uncertainty.

Did you read section 2c of the paper? It seems to be saying something very similar to the point you made about the tracking uncertainty:

for a fixed S/R [relative uncertainty of the closest approach distance] ratio, there is a maximum computable epistemic probability of collision. Whether or not the two satellites are on a collision course, no matter what the data indicate, the analyst will have a minimum confidence that the two satellites will not collide. That minimum confidence is determined purely by the data quality... For example, if the uncertainty in the distance between two satellites at closest approach is ten times the combined size of the two satellites, the analyst will always compute at least a 99.5% confidence that the satellites are safe, even if, in reality, they are not...

So when you say

then you must content yourself with avoiding approaches within around 100 metres, and you will be on the equivalent of the yellow line in that figure.

Is this not essentially what the confidence region approach is doing?

This raises a good point, especially with ethics and blame/credit. Before the Rootclaim debate, I gave a lab leak at about 65% confidence. After the debate and some thought, I put it much lower, <10% with a lot of my uncertainty based on my relatively low biology knowledge. If someone asks, I may say ~about 10% but I'm not enough of an expert. (I also expect if I was more of an expert or spent a lot more time, my 10% would go down, in tension to rationality)

HOWEVER that does not mean I can ethically judge the GoF researchers as if they had taken a 10% chance at killing >20 million people or about equal to killing 2 million for certain. (I do think they were reckless, biased, unethical, generally bad etc but just not capable enough to cause such harm).

There seems to be a bit of a Pascal mugging like thing going on here - if you are not an expert I can convince you that x has a ~1% chance of ending the world, therefore anyone involved is the worst person in history.

This is the same problem you get with insect welfare calculations. Insects suffer X% as much as humans, and whatever X actual humans pick, you conclude that insect suffering is a horrible moral catastrophe.

Let's say Alice and Bob both estimate a 80% chance of rain today. However, Alice has already checked a high quality weather report, and Bob hasn't and is going on vibes. When the time comes to leave the house with or without an umbrella Bob will probably choose to check the weather, and update his expectations accordingly, because it's easy, and makes it more likely that he will carry an umbrella if and only if it will rain. Whereas Alice will have to make a decision based on her current beliefs - getting even better information will be hard and expensive.

Bob took advantage of the fact that his probability distribution was more spread out than Alice's. His 80% included both the possibility that the weather report would rightly say it is going to rain and the possibility that it would wrongly forecast a sunny day. He can look at the forecast and update, and do better as a result. Alice's 80% was already conditioned on the dreary forecast, and thus narrower, and less susceptible to change.

To summarize, the information as to whether you are confident or unsure of your belief is in the shape of your probability distribution (but not in the number 80%) and if you are unsure you often have a cheap and valuable option to learn more.

(What Bob definitely wouldn't do is bet Carol the weather reporter that it will rain today at 4:1 odds. Despite betting odds supposedly reflecting your beliefs, don't bet against people you know have better information!)

A little background

I first heard about the False Confidence Theorem (FCT) a number of years ago, although at the time I did not understand why it was meaningful. I later returned to it, and the second time around, with a little more experience (and finding a more useful exposition), its importance was much easier to grasp. I now believe that this result is incredibly central to the use of Bayesian reasoning in a wide range of practical contexts, and yet seems to not be very well known (I was not able to find any mention of it on LessWrong). I think it is at the heart of some common confusions, where seemingly strong Bayesian arguments feel intuitively wrong, but for reasons that are difficult to articulate well. For example, I think it is possibly the central error that Rootclaim made in their lab-leak argument, and although the judges were able to come to the correct conclusion, the fact that seemingly no one was able to specifically nail down this issue has left the surrounding discussion muddled in uncertainty. I hope to help resolve both this and other confusions.

Satellite conjunction

The best exposition of the FCT that I have found is “Satellite conjunction analysis and the false confidence theorem." The motivating example here is the problem of predicting when satellites are likely to collide with each other, necessitating avoidance maneuvers. The paper starts by walking through a seemingly straightforward application of Bayesian statistics to compute an epistemic probability that 2 satellites will collide, given data (including uncertainty) about their current position and motion. At the end, we notice that very large uncertainties in the trajectories correspond to a very low epistemic belief of collision. Not uncertainty, but rather high confidence of safety. As the paper puts it:

And yet, from a Bayesian perspective, we might argue that this makes sense. If we have 2 satellites that look like they are on a collision course (point estimate of the minimum distance between them is 0), but those estimates are highly uncertain, we might say that the trajectories are close to random. And in that case, 2 random trajectories gives you a low collision probability. But reasoning this way simply based on uncertainty is an error. You certainly should not become more confident that 2 satellites are safe, just because you added random noise to the measurements.

As it turns out, this problem pops up in a very wide variety of contexts. The paper proves that any epistemic belief system will assign arbitrarily high probability to propositions that are false, with arbitrarily high frequentist probability. Indeed:

Moreover, there is no easy way around this result. It applies to any “epistemic belief system”, i.e. any system of assigning probabilities to statements that includes the seemingly basic law of probability that P(A) = 1 - P(not A). This occurs because of this very fact: If we cannot assign a high probability to A, we must assign substantial probability to not-A. In this case, if cannot be more than, say, 0.1% sure the satellites will collide, then we have to be at least 99.9% sure that they will not collide.

However, there is one way out (well, one way that preserves the probability rule above). This result is restricted to epistemic uncertainty, that is, uncertainty resulting from an agent’s lack of knowledge, in contrast to aleatory variability, that is, actual randomness in the behavior of the object being studied. A Bayesian might object vehemently to this distinction, but recall the motivating example. If 2 satellites are on a collision course, adding noise to the measurements of their trajectories does not make them safer. However, giving each one a random push from its jets increases the actual variation in their paths, likely pushing them away from the previous point estimate of a collision, and thus does make them safer.

The practical take-away

It is inappropriate to conflate subjective uncertainty with actual variation when reasoning under uncertainty. Doing so can result in errors of arbitrary magnitude. This phenomenon can occur, for example, when a key estimate relies on a highly uncertain parameter. Saying, “I don’t know much about this subject, but it would be overconfident to say this probability is less than 10%” sounds safe and prudent. But your lack of knowledge does not actually constrain the true value. It could in reality be 1/100, or 1/10,000, or 1/1,000,000. This arbitrarily severe error can then be carried forward, for example if the probability in question is used to compute a Bayes factor; both it and the final answer will then be off by the same (possibly very high) ratio.

Perhaps an alternative way of phrasing this fact is simply to say that uncertainty is not evidence. Bayes theorem tells you how to incorporate evidence into your beliefs. You can certainly incorporate uncertainty into your beliefs, but you can't treat them the same way.

Example 1: Other people’s (lack of) confidence

Back in the day, Scott Alexander asked the following question in reference to the claim that the probability of Amanda Knox’s guilt is on the order 1 in 1,000, when LW commenters had given an average of 35%:

In fact, komponsito was entirely correct to be confident. 35% did not represent a true evaluation of AK’s probability of guilt, based on all of the available evidence. Many commenters, by their own admission, had not thoroughly investigated the case. 35% simply represented their epistemic uncertainty on a topic they had not investigated. If every commenter had thoroughly researched the case and the resulting average was still 35%, one could ask if komponsito was being overconfident, but as it stood, the commenters’ average and his number represented entirely different things and it would be rather meaningless to compare them.

One may as well survey the community to ask whether a coin would come up heads or tails, and then after I flip it and proclaim it definitely came up heads, you accuse me of being overconfident. After all, a hundred rationalists claimed it was 50/50! (Or to take a slightly less silly example, a coin that is known to be biased, but I'm the only one who's researched how biased or in what direction).

Example 2: Heroic Bayesian analysis

In Rootclaim’s most recent COVID origins analysis, the single strongest piece of evidence is “12 nucleotides clean insertion,” which they claim is 20x more likely in lab leak (after out-of-model correction). Specifically, they say it is 10% likely under lab leak, based on the following “guesstimate:”

So, they do not have any evidence that, across all cases when researchers might try to add an FCS to a virus, they use a “12 nucleotide clean insertion” 1 time out of 10. They simply provide a guess, based on their own lack of knowledge. This is exactly the error described above: For all they actually know, the true frequency of this behavior could be 1/1,000, an error of 100x, or it could be even worse.

It is simply not valid to claim strong evidence for no other reason than your own certainty. Doing so is perverse to the extreme, and would make it trivial to make yourself completely confident by ignoring as much evidence as possible. The only valid conclusion to draw from this lack of knowledge is that you are unable to evaluate the evidence in question, and must remain uncertain.

So what should you do instead?

I believe that, essentially, avoiding FCT (at least, when epistemic uncertainty is unvaoidable) comes down to explicitly including uncertainty in your final probability estimate. The satellite conjunction paper offers a solution which bounds the probability of collision, and which can be proven to actually achieve this desired safety level. The key fact is that we are not claiming an exact value for P(collision) or its complement. The example from the satellite paper is based on “confidence regions,” i.e.

For the specific satellite case, the solution is to compute uncertainty ellipsoids for each object, and check if they overlap at the point of closest approach. In this case, the probability of collision can indeed be limited:

These tools are in some sense, "crude" ways of representing belief, as they do not reflect the full richness of the axioms of probability theory. And yet, they may be of great practical use.

Conclusion

It is perhaps quite surprising that attempting to force your beliefs to respect the seemingly obvious law of probability that P(A) = 1-P(A) can result in errors. Not just that, but it is in fact guaranteed to result in errors that are arbitrarily bad. Moreover, contrary to what “pure” or “naive” Bayesianism might indicate, there is in fact a very significant, practical difference between subjective uncertainty and aleatory variability. Nevertheless, the results seem to be on very solid mathematical ground, and once we dive into what these results are really saying, it makes a lot more intuitive sense.

Additional links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/False_confidence_theorem

https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.06217