These investors were Dustin Moskovitz, Jaan Tallinn and Sam Bankman-Fried

nitpick: SBF/FTX did not participate in the initial round - they bought $500M worth of non-voting shares later, after the company was well on its way.

more importantly, i often get the criticism that "if you're concerned with AI then why do you invest in it". even though the critics usually (and incorrectly) imply that the AI would not happen (at least not nearly as fast) if i did not invest, i acknowledge that this is a fair criticism from the FDT perspective (as witnessed by wei dai's recent comment how he declined the opportunity to invest in anthropic).

i'm open to improving my policy (which is - empirically - also correllated with the respective policies of dustin as well as FLI) of - roughly - "invest in AI and spend the proceeds on AI safety" -- but the improvements need to take into account that a) prominent AI founders have no trouble raising funds (in most of the alternative worlds anthropic is VC funded from the start, like several other openAI offshoots), b) the volume of my philanthropy is correllated with my net worth, and c) my philanthropy is more needed in the worlds where AI progresses faster.

EDIT: i appreciate the post otherwise -- upvoted!

i acknowledge that this is a fair criticism from the FDT perspective (as witnessed by wei dai's recent comment how he declined the opportunity to invest in anthropic).

To clarify a possible confusion, I do not endorse using "FDT" (or UDT or LDT) here, because the state of decision theory research is such that I am very confused about how to apply these decision theories in practice, and personally mostly rely on a mix of other views about rationality and morality, including standard CDT-based game theory and common sense ethics.

(My current best guess is that there is minimal "logical correlation" between humans so LDT becomes CDT-like when applied to humans, and standard game theory seems to work well enough in practice or is the best tool that we currently have when it comes to multiplayer situations. Efforts to ground human moral/ethical intuitions on FDT-style reasoning do not seem very convincing to me so far, so I'm just going to stick with the intuitions themselves for now.)

In this particular case, I mainly wanted to avoid signaling approval of Anthropic's plans and safety views or getting personally involved in activities that increase x-risk in my judgement. Avoiding conflicts of interest (becoming biased in favor of Anthropic in my thoughts and speech) was also an important consideration.

ah, sorry about mis-framing your comment! i tend to use the term "FDT" casually to refer to "instead of individual acts, try to think about policies and how would they apply to agents in my reference class(es)" (which i think does apply here, as i consider us sharing a plausible reference class).

My suspicion is that if we were to work out the math behind FDT (and it's up in the air right now whether this is even possible) and apply it to humans, the appropriate reference class for a typical human decision would be tiny, basically just copies of oneself in other possible universes.

One reason for suspecting this is that humans aren't running clean decision theories, but have all kinds of other considerations and influences impinging on their decisions. For example psychological differences between us around risk tolerance and spending/donating money, different credences for various ethical ideas/constraints, different intuitions about AI safety and other people's intentions, etc., probably make it wrong to think of us as belonging to the same reference class.

re first paragraph that seems wrong, a continuous relaxation of FDT seems like it ought to do what people seem to intuitively think FDT does

Does the appriopriate [soft] reference class scale with intersimulizability of agents?

i.e. generally greater more computationally powerful agents are better at simulating other agents and this will generically push towards the regime where FDT gives a larger reference class.

The asymptote would be some sort of acausal society of multiverse higher-order cooperators.

Yes, I imagine that powerful agents could eventually adopt clean (easy to reason about) decision theories, simulate other agents until they also adopt clean decision theories, and then they can reason about things like, "If I decide to X, that logically implies these other agents making decisions Y and Z".

(Except it can't be this simple, because this runs into problems with commitment races, e.g., while I'm simulating another agent, they suspect this and as a result make a bunch of commitments that give themselves more bargaining power. But something like this, more sophisticated in some way, might turn out to work.)

I think FDT/UDT only allows you to influence the decisions of other people who also believe in FDT/UDT.[1]

No matter how strongly you cooperate, if the reason you decide to cooperate is because of FDT/UDT, then that means you still would have defected if you didn't believe FDT/UDT, and therefore other people (whose decisions correlate with you) will still defect just like before, regardless of how strongly FDT/UDT makes you cooperate.

- ^

Assuming there are no complicated simulations or acausal trade commitments.

Re "invest in AI and spend the proceeds on AI safety" - another consideration other than the ethical (/FDT) concerns, is that of liquidity. Have you managed to pull out any profits from Anthropic yet? If not, how likely do you think it is that you will be able to[1] before the singularity/doom?

- ^

Maybe this would require an IPO?

indeed, illiquidity is a big constraint to my philanthropy, so in very short timelines my “invest (in startups) and redistribute” policy does not work too well.

You're right – I put Series A and Series B together here. I should make the distinction.

but the improvements need to take into account that a) prominent AI founders have no trouble raising funds (in most of the alternative worlds anthropic is VC funded from the start, like several other openAI offshoots)

There is a question about whether the safety efforts your money supported at or around the companies ended up compensating for the developments at / extra competition encouraged by the companies.

It seems that if Dustin and you had not funded Series A of Anthropic, they would have had a harder time starting up. If moreso, the broader community had oriented much differently around whether to support Anthropic at the time – considering the risk of accelerating work at another company – Anthropic could have lost a large part of its support base. The flipside here is that the community would have actively alienated Anthropic's founders and would have lost influence over work at Anthropic as well as any monetary gains. I think it would have been better to instead coordinate to not enable another AGI-development company to get off the ground, but curious for your and others' thoughts.

b) the volume of my philanthropy is correllated with my net worth, and c) my philanthropy is more needed in the worlds where AI progresses faster.

This part makes sense to me.

I've been wondering about this. Just looking at the SFF grants (recognising that you might still make grants elsewhere), the amounts have definitely been going up (from $16 million in 2022 to $41 million in 2024). At the same time there have been rounds where SFF evaluators could not make grants that they wanted to. Does this have to do with liquidity issues or something else? It seems that your net worth can cover larger grants, but there must be a lot of considerations here.

There is a question about whether the safety efforts your money supported at or around the companies ended up compensating for the developments

yes. more generally, sign uncertainty sucks (and is a recurring discussion topic in SFF round debates).

It seems that if Dustin and you had not funded Series A of Anthropic, they would have had a harder time starting up.

they certainly would not have had harder time setting up the company nor getting the equivalent level of funding (perhaps even at a better valuation). it’s plausible that pointing to “aligned” investors helped with initial recruiting — but that’s unclear to me. my model of dario/founders just did not want the VC profit-motive to play a big part in the initial strategy.

Does this have to do with liquidity issues or something else?

yup, liquidity (also see the comments below), crypto prices, and about half of my philanthropy not being listed on that page. also SFF s-process works with aggregated marginal value functions, so there is no hard cutoff (hence the “evaluators could not make grants that they wanted to” sentence makes less sense than in traditional “chunky and discretionary” philanthropic context).

This is clarifying. Appreciating your openness here.

I can see how Anthropic could have started out with you and Dustin as ‘aligned’ investors, but that around that time (the year before ChatGPT) there was already enough VC interest that they could probably have raised a few hundred millions anyway

Thinking about your invitation here to explore ways to improve:

i'm open to improving my policy (which is - empirically - also correllated with the respective policies of dustin as well as FLI) of - roughly - "invest in AI and spend the proceeds on AI safety"

Two thoughts:

When you invest in an AI company, this could reasonably be taken as a sign that you are endorsing their existence. Doing so can also make it socially harder later to speak out (e.g. on Anthropic) in public.

Has it been common for you to have specific concerns that a start-up could or would likely do more harm than good – but you decide to invest because you expect VCs would cover the needed funds anyway (but not grant investment returns to ‘safety’ work, nor advise execs to act more prudently)?

In that case, could you put out those concerns in public before you make the investment? Having that open list seems helpful for stakeholders (e.g. talented engineers who consider applying) to make up their own mind and know what to watch out for. It might also help hold the execs accountable.

The grant priorities for restrictive efforts seem too soft.

Pursuing these priorities imposes little to no actual pressure on AI corporations to refrain from reckless model development and releases. They’re too complicated and prone to actors finding loopholes, and most of them lack broad-based legitimacy and established enforcement mechanisms.

Sharing my honest impressions here, but recognising that there is a lot of thought put behind these proposals and I may well be misinterpreting them (do correct me):

The liability laws proposal I liked at the time. Unfortunately, it’s become harder since then to get laws passed given successful lobbying of US and Californian lawmakers who are open to keeping AI deregulated. Though maybe there are other state assemblies that are less tied up by tech money and tougher on tech that harms consumers (New York?).

The labelling requirements seem like low-hanging fruit. It’s useful for informing the public, but applies little pressure on AI corporations to not go further ‘off the rails’.

The veto committee proposal provides a false sense of security with little teeth behind it. In practice, we’ve seen supposedly independent boards, trusts, committees and working groups repeatedly fail to carry out their mandates (at DM, OAI, Anthropic, UK+US safety institute, the EU AI office, etc) because nonaligned actors could influence them to, or restructure them, or simply ignore or overrule their decisions. The veto committee idea is unworkable, in my view, because we first need to deal with a lack of real accountability and capacity for outside concerned coalitions to impose pressure on AI corporations.

Unless the committee format is meant as a basis for wider inquiry and stakeholder empowerment? A citizen assembly for carefully deliberating a crucial policy question (not just on e.g. upcoming training runs) would be useful because it encourages wider public discussion and builds legitimacy. If the citizen’s assembly mandate gets restricted into irrelevance or its decision gets ignored, a basis has still been laid for engaged stakeholders to coordinate around pushing that decision through.

The other proposals – data centre certification, speed limits, and particularly the global off-switch – appear to be circuitous, overly complicated and mostly unestablished attempts at monitoring and enforcement for mostly unknown future risks. They look technically neat, but create little ingress capacity for different opinionated stakeholders to coordinate around restricting unsafe AI development. I actually suspect that they’d be a hidden gift for AGI labs who can go along with the complicated proceedings and undermine them once no longer useful for corporate HQ’s strategy.

Direct and robust interventions could e.g. build off existing legal traditions and widely shared norms, and be supportive of concerned citizens and orgs that are already coalescing to govern clearly harmful AI development projects.

An example that comes to mind: You could fund coalition-building around blocking the local construction of and tax exemptions for hyperscale data centers by relatively reckless AI companies (e.g. Meta). Some seasoned organisers just started working there, and they are supported by local residents, environmentalist orgs, creative advocates, citizen education media, and the broader concerned public. See also Data Center Watch.

1. i agree. as wei explicitly mentions, signalling approval was a big reason why he did not invest, and it definitely gave me a pause, too (i had a call with nate & eliezer on this topic around that time). still, if i try to imagine a world where i declined to invest, i don't see it being obviously better (ofc it's possible that the difference is still yet to reveal itself).

concerns about startups being net negative are extremely rare (outside of AI, i can't remember any other case -- though it's possible that i'm forgetting some). i believe this is the main reason why VCs and SV technologists tend to be AI xrisk deniers (another being that it's harder to fundraise as a VC/technologist if you have sign uncertainty) -- their prior is too strong to consider AI an exception. a couple of years ago i was at an event in SF where top tech CEOs talked about wanting to create "lots of externalties", implying that externalities can only be positive.

2. yeah, the priorities page is now more than a year old and in bad need of an update. thanks for the criticism -- fwded to the people drafting the update.

I revised the footnote to make the Series A v.s B distinction. I also interpreted your comment to mean that series A investments were in voting shares but do please correct:

These investors were Dustin Moskovitz and Jaan Tallinn in Series A, and Sam Bankman-Fried about a year later in Series B.

Dustin was advised to invest by Holden Karnofsky. Sam invested $500 million through FTX, by far the largest investment, though it was in non-voting shares.

I joined Anthropic in 2021 because I thought it was an extraordinarily good way to help make AI go well for humanity, and I have continued to think so. If that changed, or if any of my written lines were crossed, I'd quit.

I think many of the factual claims in this essay are wrong (for example, neither Karen Hao nor Max Tegmark are in my experience reliable sources on Anthropic); we also seem to disagree on more basic questions like "has Anthropic published any important safety and interpretability research", and whether commercial success could be part of a good AI Safety strategy. Overall this essay feels sufficiently one-sided and uncharitable that I don't really have much to say beyond "I strongly disagree, and would have quit and spoken out years ago otherwise".

I regret that I don't have the time or energy for a more detailed response, but thought it was worth noting the bare fact that I have detailed views on these issues (including a lot of non-public information) and still strongly disagree.

if any of my written lines were crossed, I'd quit.

Just out of curiosity, what are your written lines? I am not sure whether this was intended as a reference to lines you wrote yourself internally, or something you feel comfortable sharing. No worries if not, I would just find it helpful for orienting to things.

These are personal committments which I wrote down before I joined, or when the topic (e.g. RSP and LTBT) arose later. Some are 'hard' lines (if $event happens); others are 'soft' (if in my best judgement ...) and may say something about the basis for that judgement - most obviously that I won't count my pay or pledged donations as a reason to avoid leaving or speaking out.

I'm not comfortable giving a full or exact list (cf), but a sample of things that would lead me to quit:

- If I thought that Anthropic was on net bad for the world.

- If the LTBT was abolished without a good replacement.

- Severe or willful violation of our RSP, or misleading the public about it.

- Losing trust in the integrity of leadership.

[Feel free not to respond / react with the "not worth getting into" emoji"]

Severe or willful violation of our RSP, or misleading the public about it.

Should this be read as "[Severe or willful violation of our RSP] or [misleading the public about the RSP]" or should this be read as "[Severe or willful violation of our RSP] or [Severe or willful misleading the public about the RSP]".

In my views/experience, I'd say there are instances where the public and (perhaps more strongly) Anthropic employees have been misled about the RSP somewhat willfully (e.g., there's an obvious well known important misconception that is convenient for Anthropic leadership and that wasn't corrected), though I guess I wouldn't consider this to be a severe violation.

If the LTBT was abolished without a good replacement.

Curious about how you'd relate to the "the LTBT isn't applying any meaningful oversight, Anthropic leadership has strong control over board appointments, and this isn't on track to change (and Anthropic leadership isn't really trying to change this)". I'd say this is the current status quo. This is kind of a tricky thing to do well, but it doesn't really seem from the outside like Anthropic is actually trying on this. (Which is maybe a reasonable choice, because idk if the LTBT was ever really that important given realistic constraints, but you see to think it is important.)

I think it is simply false that Anthropic leadership (excluding the LTB Trustees) have control over board appointments. You may argue they have influence, to the extent that the Trustees defer to their impressions or trust their advice, but formal control of the board is a very different thing. The class T shares held by the LTBT are entitled to appoint a majority of the board, and that cannot change without the approval of the LTBT.[1]

Delaware law gives the board of a PBC substantial discretion in how they should balance shareholder profits, impacts on the public, and the mission of the organization. Again, I trust current leadership, but think it is extremely important that there is a legally and practically binding mechanism to avoid that balance being set increasingly towards shareholders rather than the long-term benefit of humanity - even as the years go by, financial stakes rise, and new people take leadership roles.

In addition to appointing a majority of the board, the LTBT is consulted on RSP policy changes (ultimately approved by the LTBT-controlled board), and they receive Capability Reports and Safeguards Reports before the company moves forward with a model release. IMO it's pretty reasonable to call this meaningful oversight - the LTBT is a backstop to ensure that the company continues to prioritize the mission rather than a day-to-day management group, and I haven't seen any problems with that.

or making some extremely difficult amendments to the Trust arrangements; you can read Anthropic's certificate of incorporation for details. I'm not linking to it here though, because the commentary I've seen here previously has misunderstood basic parts like "who has what kind of shares" pretty badly. ↩︎

I certainly agree that the LTBT has de jure control (or as you say "formal control").

By "strong control" I meant more precisely something like: "lots of influence in practice, e.g. the influence of Anthropic leadership is comparable to the influence that the LTBT itself is exerting in practice over appointments or comparable (though probably less) to the influence that (e.g.) Sam Altman has had over recent board appointments at OpenAI". Perhaps "it seems like they have a bunch of control" would have been a more accurate way to put things.

I think it would be totally unsurprising for the LTBT to have de jure power but not that much de facto power (given the influence of Anthropic leadership) and from the outside it sure looks like this is the case at the moment.

See this Time article, which was presumably explicitly sought out by Anthropic to reassure investors in the aftermath of the OpenAI board crisis, in which Brian Israel (at the time general counsel at Anthropic) is paraphrased as repeatedly saying (to investors) "what happened at OpenAI can't happen to us". The article (again, likely explicitly sought out by Anthropic as far as I can tell) also says "it also means that the LTBT ultimately has a limited influence on the company: while it will eventually have the power to select and remove a majority of board members, those members will in practice face similar incentives to the rest of the board." For what it's worth, I think the implication of the article is wrong and the LTBT actually has very strong de jure power (optimistically, the journalist misinterpreted Brian Israel and wrote a misleading article), but it sure seems like Anthropic leadership wanted to create the impression that the power of the LTBT is limited to reassure shareholders (which does actually weaken the LTBT: the power of institutions is partially based on perception, see e.g. the OpenAI board).

I find the board appointments of the LTBT to not be reassuring; these hires seem unlikely to result in serious oversight of the company due to insufficient expertise and not being dedicated full-time board members. I also don't find it reassuring that these hires were made far after when they were supposed to be made and that the LTBT hasn't filled its empty seats. (At least based on public information.)

All these concerns wouldn't be a big deal if this was a normal company rather than a company aiming to build AGI: probably the single largest danger to humanity as well as the most dangerous and important technology ever (as I expect people at Anthropic would agree).

(See also my discussion of the LTBT in this comment, though I think I say strictly more here.)

I could imagine the LTBT stepping up to take on a more serious oversight role and it seems plausible this will happen in the future, but as it stands public evidence makes it look like the de facto power being exerted by the LTBT is very limited. It's hard for me to have much confidence either way with my limited knowledge.

To be clear, my view is that this situation is substantially the fault of current LTBT members (who in my view should probably think of governing Anthropic as their top priority and do this full time).

Here are some (possibly costly) actions that Anthropic or the LTBT could take which would (partially) reassure me:

- Designate a member of the alignment science team to report periodically to the LTBT directly. Ideally, this person would be employed by the LTBT rather than by Anthropic (e.g. Anthropic can't fire them) and wouldn't have equity so they are less financially conflicted. It should be public who this is. This could be someone on the alignment stress testing sub-team. I think DMZ is the person with the position at Anthropic that is most naturally suited to do this. I have other specific candidates in mind and could share privately on request.

- The LTBT generally acquires more full-time staff who are independent from the company.

- Dario states internally in a clear way that he wouldn't aggressively maneuver against the board (or the LTBT) if they were trying to remove him or otherwise do something he disagreed with. And, that Anthropic employees shouldn't join in efforts to undermine the (de jure) power of the board if this happened. This wouldn't be verifiable externally (unless Dario said this publicly), but I do think it meaningfully ties Dario's hands (because a major source of power Dario has is strong employee loyalty). As far as I know, Dario could have already done this, but I'm skeptical this has happened on priors.

- Some member(s) of the LTBT become full time on the job of being an LTBT member and spend a bunch of time talking to employees and external experts etc. This would ideally be a new LTBT member who has domain expertise. Substantially more time would also help.

- The hiring process for new board members by the LTBT is changed to enforce strong separation between the LTBT and the existing board/leadership via not providing any information to the existing board or Anthropic leadership until the hire is decided. This seems very costly and I'm not sure I'd recommend this, but it would address my particular concerns. I think this could be a good choice if the LTBT had independent staff and full-time LTBT members.

To be clear, my view is that Anthropic is currently overall the best governed/managed company trying to build AGI, but this is due to my views about Dario and other Anthropic executives (which are partially based on connections and private knowledge) rather than due to the LTBT. And I don't think "best governed/managed AGI company" is a very high bar.

The Time article is materially wrong about a bunch of stuff - for example, there is a large difference between incentives and duties; all board members have the same duties but LTBT appointees are likely to have a very different equity stake to whoever is in the CEO board seat.

I really don't want to get into pedantic details, but there's no "supposed to" time for LTBT board appointments, I think you're counting from the first day they were legally able to appoint someone. Also https://www.anthropic.com/company lists five board members out of five seats, and four Trustees out of a maximum five. IMO it's fine to take a few months to make sure you've found the right person!

More broadly, the corporate governance discussions (not just about Anthropic) I see on LessWrong and in the EA community are very deeply frustrating, because almost nobody seems to understand how these structures normally function or why they're designed that way or the failure modes that occur in practise. Personally, I spent about a decade serving on nonprofit boards, oversight committes which appointed nonprofit boards, and set up the goverance for a for-profit company I founded.

I know we love first-principles thinking around here, but this is a domain with an enormous depth of practice, crystalized from long experience of (often) very smart people in sometimes-adversarial situations.

In any case, I think I'm done with this thread.

The Time article is materially wrong about a bunch of stuff

Agreed which is why I noted this in my comment.[1] I think it's a bad sign that Anthropic seemingly actively sought out an article that ended up being wrong/misleading in a way which was convenient for Anthropic at the time and then didn't correct it.

I really don't want to get into pedantic details, but there's no "supposed to" time for LTBT board appointments, I think you're counting from the first day they were legally able to appoint someone. Also https://www.anthropic.com/company lists five board members out of five seats, and four Trustees out of a maximum five. IMO it's fine to take a few months to make sure you've found the right person!

First, I agree that there isn't a "supposed to" time, my wording here was sloppy, sorry about that.

My understanding was a that there was a long delay (e.g. much longer than a few months) between the LTBT being able to appoint a board member and actually appointing such a member and a long time where the LTBT only had 3 members. I think this long of a delay is somewhat concerning.

My understanding is that the LTBT could still decide one more seat (so that it determines a majority of the board). (Or maybe appoint 2 additional seats?) And that it has been able to do this for almost a year at this point. Maybe the LTBT thinks the current board composition is good such that appointments aren't needed, but the lack of any external AI safety expertise on the board or LTBT concerns me...

More broadly, the corporate governance discussions (not just about Anthropic) I see on LessWrong and in the EA community are very deeply frustrating, because almost nobody seems to understand how these structures normally function or why they're designed that way or the failure modes that occur in practise. Personally, I spent about a decade serving on nonprofit boards, oversight committes which appointed nonprofit boards, and set up the goverance for a for-profit company I founded.

I certainly don't have particular expertise in corporate governance and I'd be interested in whether corporate governance experts who are unconflicted and very familiar with the AI situation think that the LTBT has the de facto power needed to govern the company through transformative AI. (And whether the public evidence should make me much less concerned about the LTBT than I would be about the OpenAI board.)

My view is that the normal functioning of a structure like the LTBT or a board would be dramatically insufficient for governing transformative AI (boards normally have a much weaker function in practice than the ostensible purposes of the LTBT and the Anthropic board), so I'm not very satisfied by "the LTBT is behaving how a body of this sort would/should normally behave".

I said something weaker: "For what it's worth, I think the implication of the article is wrong and the LTBT actually has very strong de jure power", because I didn't see anything which is literally false as stated as opposed to being misleading. But you'd know better. ↩︎

I think it's a bad sign that Anthropic seemingly actively sought out an article that ended up being wrong/misleading in a way which was convenient for Anthropic at the time and then didn't correct it.

Yep; misleading the public about this doesn’t exactly boost confidence in how much Anthropic would prioritize integrity/commitments/etc. when their interests are on the line.

I honestly haven't thought especially in depth or meaningfully about the LTBT and this is zero percent a claim about the LTBT, but as someone who has written a decent number of powerpoint decks that went to boards and used to be a management consultant and corporate strategy team member, I would generally be dissatisfied with the claim that a board's most relevant metric is how many seats it currently has filled (so long as it has enough filled to meet quorum).

As just one example, it is genuinely way easier than you think for a board to have a giant binder full of "people we can emergency appoint to the board, if we really gotta" and be choosing not to exercise that binder because, conditional on no-emergency, they genuinely and correctly prefer waiting for someone being appointed to the board who has an annoying conflict that they're in the process of resolving (e.g., selling off shares in a competitor or waiting out a post-government-employment "quiet period" or similar).

My view is that the normal functioning of a structure like the LTBT or a board would be dramatically insufficient for governing transformative AI (boards normally have a much weaker function in practice than the ostensible purposes of the LTBT and the Anthropic board), so I'm not very satisfied by "the LTBT is behaving how a body of this sort would/should normally behave".

I basically completely agree. For a related intuition pump, I have very little confidence that auditing AI capabilities company will meaningfully assist in governing transformative AI.

the LTBT is consulted on RSP policy changes (ultimately approved by the LTBT-controlled board), and they receive Capability Reports and Safeguards Reports before the company moves forward with a model release.

These details are clarifying, thanks! Respect for how LTBT trustees are consistently kept in the loop with reports.

The class T shares held by the LTBT are entitled to appoint a majority of the board

...

Again, I trust current leadership, but think it is extremely important that there is a legally and practically binding mechanism to avoid that balance being set increasingly towards shareholders rather than the long-term benefit of humanity

...

the LTBT is a backstop to ensure that the company continues to prioritize the mission rather than a day-to-day management group, and I haven't seen any problems with that.

My main concern is that based on the public information I've read, the board is not set up to fire people in case there is some clear lapse of responsibility on "safety".

Trustees' main power is to appoint (and remove?) board members. So I suppose that's how they act as a backstop. They need to appoint board members who provide independent oversight and would fire Dario if that turns out to be necessary. Even if people in the company trust him now.

Not that I'm saying that trustees appointing researchers from the safety community (who are probably in Dario's network anyway) robustly provides for that. For one, following Anthropic's RSP is not actually responsible in my view. And I suppose only safety folks who are already mostly for the RSP framework would be appointed as board members.

But it seems better to have such oversight than not.

OpenAI's board had Helen Toner, someone who acted with integrity in terms of safeguarding OpenAI's mission when deciding to fire Sam Altman.

Anthropic's board now has the Amodei siblings and three tech leaders – one brought in after leading an investment round, and the other two brought in particularly for their experience in scaling tech companies. I don't really know these tech leaders. I only looked into Reed Hastings before, and in his case there is some coverage of his past dealings with others that make me question his integrity.

~ ~ ~

Am I missing anything here? Recognising that you have a much more comprehensive/accurate view of how Anthropic's governance mechanisms are set up.

Sure, thanks for noting it.

You're always welcome to point out any factual claim that was incorrect. I had to mostly go off public information. So I can imagine that some things I included are straight-up wrong, or lack important context, etc.

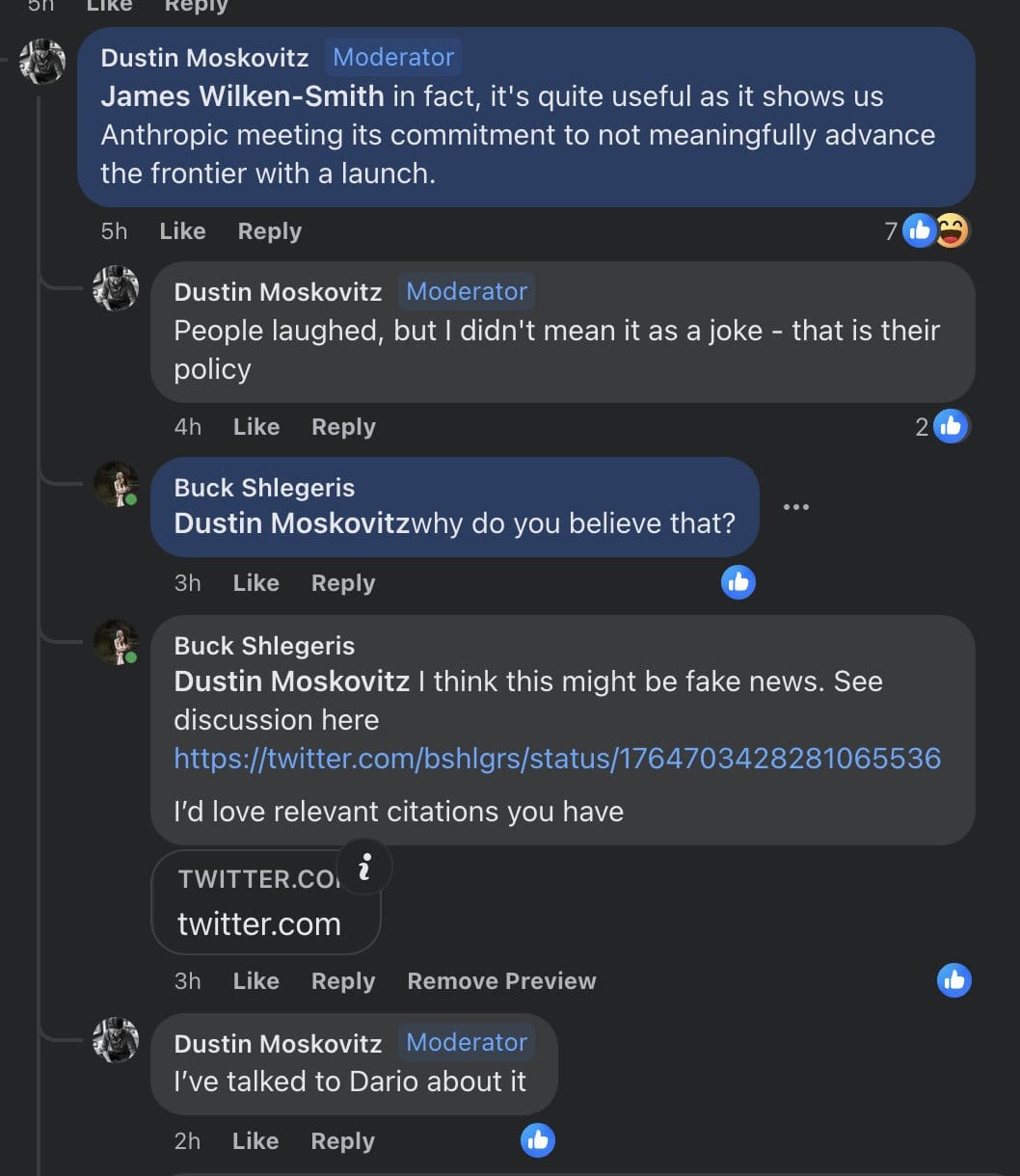

Periodically I've considered writing a post similar to this. A piece that I think this doesn't fully dive into is "did Anthropic have a commitment not to push the capability frontier?".

I had once written a doc aimed at Anthropic employees, during SB 1047 Era, when I had been felt like Anthropic was advocating for changes to the law that were hard to interpret un-cynically.[1] I've had a vague intention to rewrite this into a more public facing thing, but, for now I'm just going to lift out the section talking about the "pushing the capability frontier" thing.

When I chatted with several anthropic employees at the happy hour a

couple months~year ago, at some point I brought up the “Dustin Moskowitz’s earnest belief was that Anthropic had an explicit policy of not advancing the AI frontier” thing. Some employees have said something like “that was never an explicit commitment. It might have been a thing we were generally trying to do a couple years ago, but that was more like “our de facto strategic priorities at the time”, not “an explicit policy or commitment.”When I brought it up, the vibe in the discussion-circle was “yeah, that is kinda weird, I don’t know what happened there”, and then the conversation moved on.

I regret that. This is an extremely big deal. I’m disappointed in the other Anthropic folk for shrugging and moving on, and disappointed in myself for letting it happen.

First, recapping the Dustin Moskowitz quote (which FYI I saw personally before it was taken down)

First, gwern also claims he talked to Dario and came away with this impression:

> Well, if Dustin sees no problem in talking about it, and it's become a major policy concern, then I guess I should disclose that I spent a while talking with Dario back in late October 2022 (ie. pre-RSP in Sept 2023), and we discussed Anthropic's scaling policy at some length, and I too came away with the same impression everyone else seems to have: that Anthropic's AI-arms-race policy was to invest heavily in scaling, creating models at or pushing the frontier to do safety research on, but that they would only release access to second-best models & would not ratchet capabilities up, and it would wait for someone else to do so before catching up. So it would not contribute to races but not fall behind and become irrelevant/noncompetitive.

> And Anthropic's release of Claude-1 and Claude-2 always seemed to match that policy - even if Claude-2 had a larger context window for a long time than any other decent available model, Claude-2 was still substantially weaker than ChatGPT-4. (Recall that the causus belli for Sam Altman trying to fire Helen Toner from the OA board was a passing reference in a co-authored paper to Anthropic not pushing the frontier like OA did.)

I get that y’all have more bits of information than me about what Dario is like. But, some major hypotheses you need to be considering here are a spectrum between:

- Dustin Moskowitz and Gwern both interpreted Dario’s claims as more like commitments than Dario meant, and a reasonable bystander would attribute this more to Dustin/Gwern reading too much into it.

- Dario communicated poorly, in a way that was maybe understandable, but predictably would leave many people confused.

- Dario in fact changed his mind explicitly (making this was more like a broken commitment, and subsequent claims that it was not a broken commitment more like lies)

- Dario deliberately phrased things in an openended/confusing way, optimized to be reassuring to a major stakeholder without actually making the commitments that would have backed up that reassurance.

- Dario straight up lied to both of them.

- Dario is lying to/confusing himself.

This is important because:

a) even option 2 seems pretty bad given the stakes. I might cut many people slack for communicating poorly by accident, but when someone is raising huge amounts of money, building technology that is likely to be very dangerous by default, accidentally misleading a key stakeholder is not something you can just shrug off.

b) if we’re in worlds with options 3, 4 or 5 or 6 (and, really, even option 2), you should be more skeptical of other reassuring things Dario has said. It’s not that important to distinguish between these two because the question isn’t “how good a person is Dario?”, it’s “how should you interpret and trust things Dario says”.

In my last chat with Anthropic employees, people talked about meetings and slack channels where people asked probing, important questions, and Dario didn’t shy away from actually answering them, in a way that felt compelling. But, if Dario is skilled at saying things to smart people with major leverage over him that sound reassuring, but leave them with a false impression, you need to be a lot more skeptical of your-sense-of-having-been-reassured.

- ^

in particular, advocating for removing the whistleblower clause, and simulaneously arguing that "we don't know how to make a good SSP yet, which is why there shouldn't yet be regulations about how to do it" while also arguing "companies liability for catastrophic harms should be dependent on how good their SSP was."

I keep checking back here to see if people have responded to this seemingly cut and dry breach of promise by the leadership, but the lack of commentary is somewhat worrying.

I am in the camp that thinks that it is very good for people concerned about AI risk to be working at the frontier of development. I think it's good to criticize frontier labs who care and pressure them but I really wish it wasn't made with the unhelpful and untrue assertion that it would be better if Anthropic hadn't been founded or supported.

The problem, as I argued in this post, is that people way overvalue accelerating timelines and seem willing to make tremendous sacrifices just to slow things down a small amount. If you advocate that people concerned about AI risk avoid working on AI capabilities, the first order effect of this is filtering AI capability researchers so that they care less about AI risk. Slowing progress down is a smaller, second order effect. But many people seem to take it for granted that completely ceding frontier AI work to people who don't care about AI risk would be preferable because it would slow down timelines! This seems insane to me. How much time would possibly need to be saved for that to be worth it?

To try to get to our crux: I've found that caring significantly about accelerating timelines seems to hinge on a very particular view of alignment where pragmatic approaches by frontier labs are very unlikely to succeed, whereas some alternative theoretical work that is unrelated to modern AI has a high chance of success. I think we can see that here:

I skip details of technical safety agendas because these carry little to no weight. As far as I see, there was no groundbreaking safety progress at or before Anthropic that can justify the speed-up that their researchers caused. I also think their minimum necessary aim is intractable (controlling ‘AGI’ enough, in time or ever, to stay safe[4]).

I have the opposite view - successful alignment work is most likely to come out of people who work closely with cutting edge AI and who are using the modern deep learning paradigm. Because of this I think it's great that so many leading AI companies care about AI risk, and I think we would be in a far worse spot if we were in a counterfactual world where OpenAI/DeepMind/Anthropic had never been founded and LLMs had (somehow) not been scaled up yet.

ignoring whether anthropic should exist or not, the claim

successful alignment work is most likely to come out of people who work closely with cutting edge AI and who are using the modern deep learning paradigm

(which I agree with wholeheartedly,)

does not seem like the opposite of the claim

there was no groundbreaking safety progress at or before Anthropic

both could be true in some world. and then,

pragmatic approaches by frontier labs are very unlikely to succeed

I believe this claim, if by "succeed" we mean "directly result in solving the technical problem well enough that the only problems that remain are political, and we now could plausibly make humanity's consensus nightwatchman ai and be sure it's robust to further superintelligence, if there was political will to do so"

but,

alternative theoretical work that is unrelated to modern AI has a high chance of success

I don't buy this claim. I actually doubt there are other general learning techniques out there in math space at all, because I think we're already just doing "approximation of bayesian updating on circuits". BUT, I also currently think we cannot succeed (as above) without theoretical work that can get us from "well we found some concepts in the model..." to "...and now we have certified the decentralized nightwatchman for good intentions sufficient to withstand the weight of all other future superhuman minds' mutation-inducing exploratory effort".

I claim theoretical work of relevance needs to be immediately and clearly relevant to deep learning as soon as it comes out if it's going to be of use. Something that can't be used on deep learning can't be useful. (And I don't think all of MIRI's work fails this test, though most does, I could go step through and classify if someone wants.)

I don't think I can make reliably true claims about anthropic's effects with the amount of information I have, but their effects seem suspiciously business-success-seeking to me, in a way that seems like it isn't prepared to overcome the financial incentives I think are what mostly kill us anyway.

I actually doubt there are other general learning techniques out there in math space at all, because I think we're already just doing "approximation of bayesian updating on circuits"

Interesting perspective! I think I agree with this in practice although not in theory (I imagine there are some other ways to make it work, I just think they're very impractical compared to deep learning).

I don't think I can make reliably true claims about anthropic's effects with the amount of information I have, but their effects seem suspiciously business-success-seeking to me, in a way that seems like it isn't prepared to overcome the financial incentives I think are what mostly kill us anyway.

Part of my frustration is that I agree there are tons of difficult pressures on people at frontier AI companies, and I think sometimes they bow to these pressures. They hedge about AI risk, they shortchange safety efforts, they unnecessarily encourage race dynamics. I view them as being in a vitally important and very difficult position where some mistakes are inevitable, and I view this as just another type of mistake that should be watched for and fixed.

But instead, these mistakes are used as just another rock to throw - any time they do something wrong, real or imagined, people use this as a black mark against them that proves they're corrupt or evil. I think that's both untrue and profoundly unhelpful.

Slowing progress down is a smaller, second order effect. But many people seem to take it for granted that completely ceding frontier AI work to people who don't care about AI risk would be preferable because it would slow down timelines!

It would be good to discuss specifics. When it comes to Dario & co's scaling of GPT, it is plausible that a ChatGPT-like product would not have been developed without that work (see this section).

They made a point at the time of expressing concern about AI risk. But what was the difference they made here?

caring significantly about accelerating timelines seems to hinge on a very particular view of alignment where pragmatic approaches by frontier labs are very unlikely to succeed, whereas some alternative theoretical work that is unrelated to modern AI has a high chance of success.

It does not hinge though on just that view. There are people with very different worldviews (e.g. Yudkowsky, me, Gebru) who strongly disagree on fundamental points – yet still concluded that trying to catch up on 'safety' with current AI companies competing to release increasingly unscoped and complex models used to increasingly automate tasks is not tractable in practice.

I'm noticing that you are starting from the assumption that it is a tractibly solvable problem – particularly by "people who work closely with cutting edge AI and who are using the modern deep learning paradigm".

A question worth looking into: how can we know whether the long-term problem is actually solvable? Is there a sound basis for believing that there is any algorithm we could build in that would actually keep controlling a continuously learning and self-manufacturing 'AGI' to not cause the extinction of humans (over at least hundreds of years, above some soundly guaranteeable and acceptably high probability floor)?

They made a point at the time of expressing concern about AI risk. But what was the difference they made here?

I think you're right that releasing GPT-3 clearly accelerated timelines with no direct safety benefit, although I think there are indirect safety benefits of AI-risk-aware companies leading the frontier.

You could credibly accuse me of shifting the goalposts here, but in GPT-3 and GPT-4's case I think the sooner they came out the better. Part of the reason the counterfactual world where OpenAI/Anthropic/DeepMind had never been founded and LLMs had never been scaled up seems so bad to me is that not only do none of the leading AI companies care about AI risk, but also once LLMs do get scaled up, everything will happen much faster because Moore's law will be further along.

It does not hinge though on just that view. There are people with very different worldviews (e.g. Yudkowsky, me, Gebru) who strongly disagree on fundamental points – yet still concluded that trying to catch up on 'safety' with current AI companies competing to release increasingly unscoped and complex models used to increasingly automate tasks is not tractable in practice.

Gebru thinks there is no existential risk from AI so I don't really think she counts here. I think your response somewhat confirms my point - maybe people vary on how optimistic they are about alternative theoretical approaches, but the common thread is strong pessimism about the pragmatic alignment work frontier labs are best positioned to do.

I'm noticing that you are starting from the assumption that it is a tractibly solvable problem – particularly by "people who work closely with cutting edge AI and who are using the modern deep learning paradigm".A question worth looking into: how can we know whether the long-term problem is actually solvable? Is there a sound basis for believing that there is any algorithm we could build in that would actually keep controlling a continuously learning and self-manufacturing 'AGI' to not cause the extinction of humans (over at least hundreds of years, above some soundly guaranteeable and acceptably high probability floor)?

I agree you won't get such a guarantee, just like we don't have a guarantee that a LLM will learn grammar or syntax. What we can get is something that in practice works reliably. The reason I think it's possible is that a corrigible and non-murderous AGI is a coherent target that we can aim at and that AIs already understand. That doesn't mean we're guaranteed success mind you but it seems pretty clearly possible to me.

Just a note here that I'm appreciating our conversation :) We clearly have very different views right now on what is strategically needed but digging your considered and considerate responses.

but also once LLMs do get scaled up, everything will happen much faster because Moore's law will be further along.

How do you account for the problem here that Nvidia's and downstream suppliers' investment in GPU hardware innovation and production capacity also went up as a result of the post-ChatGPT race (to the bottom) between tech companies on developing and releasing their LLM versions?

I frankly don't know how to model this somewhat soundly. It's damn complex.

Gebru thinks there is no existential risk from AI so I don't really think she counts here.

I was imagining something like this response yesterday ('Gebru does not care about extinction risks').

My sense is that the reckless abandon of established safe engineering practices is part of what got us into this problem in the first place. I.e. if the safety community had insisted that models should be scoped and tested like other commercial software with critical systemic risks, we would be in a better place now.

It's a more robust place to come from than the stance that developments will happen anyway – but that we somehow have to catch up by inventing safety solutions generally applicable to models auto-encoded on our general online data to have general (unknown) functionality, used by people generally to automate work in society.

If we'd manage to actually coordinate around not engineering stuff that Timnit Gebru and colleagues would count as 'unsafe to society' according to say the risks laid out in the Stochastic Parrots paper, we would also robustly reduce the risk of taking a mass extinction all the way. I'm not saying that is easy at all, just that it is possible for people to coordinate on not continuing to develop risky resource-intensive tech.

but the common thread is strong pessimism about the pragmatic alignment work frontier labs are best positioned to do.

This is agree with. So that's our crux.

This not a very particular view – in terms of the possible lines of reasoning and/or people with epistemically diverse worldviews that end up arriving at this conclusion. I'd be happy to discuss the reasoning I'm working from, in the time that you have.

I agree you won't get such a guarantee

Good to know.

I was not clear enough with my one-sentence description. I actually mean two things:

- No sound guarantee of preventing 'AGI' from causing extinction (over the long-term, above some acceptably high probability floor), due to fundamental control bottlenecks in tracking and correcting out the accumulation of harmful effects as the system modifies in feedback with the environment over time.

- The long-term convergence of this necessarily self-modifying 'AGI' on causing changes to the planetary environment that humans cannot survive.

The reason I think it's possible is that a corrigible and non-murderous AGI is a coherent target that we can aim at and that AIs already understand. That doesn't mean we're guaranteed success mind you but it seems pretty clearly possible to me.

I agree that this is a specific target to aim at.

I also agree that you could program for an LLM system to be corrigible (for it to correct output patterns in response to human instruction). The main issue is that we cannot build in an algorithm into fully autonomous AI that can maintain coherent operation towards that target.

Just a note here that I'm appreciating our conversation :) We clearly have very different views right now on what is strategically needed but digging your considered and considerate responses.

Thank you! Same here :)

How do you account for the problem here that Nvidia's and downstream suppliers' investment in GPU hardware innovation and production capacity also went up as a result of the post-ChatGPT race (to the bottom) between tech companies on developing and releasing their LLM versions?

I frankly don't know how to model this somewhat soundly. It's damn complex.

I think it's definitely true that AI-specific compute is further along than it would be if there hadn't been the LLM boom happening. I think the relationship is unaffected though - earlier LLM development means faster timelines but slower takeoff.

Personally I think slower takeoff is more important than slower timelines, because that means we get more time to work with and understand these proto-AGI systems. On the other hand to people who see alignment as more of a theoretical problem that is unrelated to any specific AI system, slower timelines are good because they give theory people more time to work and takeoff speeds are relatively unimportant.

But I do think the latter view is very misguided. I can imagine a setup for training a LLM in a way that makes it both generally intelligent and aligned; I can't imagine a recipe for alignment that works outside of any particular AI paradigm, or that invents its own paradigm while simultaneously aligning it. I think the reason a lot of theory-pilled people such as people at MIRI become doomers is that they try to make that general recipe and predictably fail.

This not a very particular view – in terms of the possible lines of reasoning and/or people with epistemically diverse worldviews that end up arriving at this conclusion. I'd be happy to discuss the reasoning I'm working from, in the time that you have.

I think I'd like to have a discussion about whether practical alignment can work at some point, but I think it's a bit outside the scope of the current convo. (I'm referring to the two groups here as 'practical' and 'theoretical' as a rough way to divide things up).

Above and beyond the argument over whether practical or theoretical alignment can work I think there should be some norm where both sides give the other some credit. Because in practice I doubt we'll convince each other, but we should still be able to co-operate to some degree.

E.g. for myself I think theoretical approaches that are unrelated to the current AI paradigm are totally doomed, but I support theoretical approaches getting funding because who knows, maybe they're right and I'm wrong.

And on the other side, given that having people at frontier AI labs who care about AI risk is absolutely vital for practical alignment, I take anti-frontier lab rhetoric as breaking a truce between the two groups in a way that makes AI risk worse. Even if this approach seems doomed to you, I think if you put some probability on you being wrong about it being doomed then the cost-benefit analysis should still come up robustly positive for AI-risk-aware people working at frontier labs (including on capabilities).

This is a bit outside the scope of your essay since you focused on leaders at Anthropic who it's definitely fair to say have advanced timelines by some significant amount. But for the marginal worker at a frontier lab who might be discouraged from joining due to X-risk concerns, I think the impact on timelines is very small and the possible impact on AI risk is relatively much larger.

Above and beyond the argument over whether practical or theoretical alignment can work I think there should be some norm where both sides give the other some credit …

E.g. for myself I think theoretical approaches that are unrelated to the current AI paradigm are totally doomed, but I support theoretical approaches getting funding because who knows, maybe they're right and I'm wrong.

I understand this is a common area of debate.

Both approaches do not work based on the reasoning I’ve gone through.

if we can get a guarantee, it'll also include guarantees about grammar and syntax. doesn't seem like too much to ask, might have been too much to ask to do it before the model worked at all, but SLT seems on track to give a foothold from which to get a guarantee. might need to get frontier AIs to help with figuring out how to nail down the guarantee, which would mean knowing what to ask for, but we may be able to be dramatically more demanding with what we ask for out of a guarantee-based approach than previous guarantee-based approaches, precisely because we can get frontier AIs to help out, if we know what bound we want to find.

My point was that even though we already have an extremely reliable recipe for getting an LLM to understand grammar and syntax, we are not anywhere near a theoretical guarantee for that. The ask for a theoretical guarantee seems impossible to me, even on much easier things that we already know modern AI can do.

When someone asks for an alignment guarantee I'd like them to demonstrate what they mean by showing a guarantee for some simpler thing - like a syntax guarantee for LLMs. I'm not familiar with SLT but I'll believe it when I see it.

I completely agree with this! I think lots of people here are so focused on slowing down AI that they forget the scope of things. According to Remmelt himself, $600 billion+ is being invested yearly into AI. Yet AI safety spending is less than $0.2 billion.

Even if money spent on AI capabilities speeds up capabilities far more efficiently than money spent on AI alignment speeds up alignment, it's far easier to grow AI alignment effort by twofold, and far harder to make even a dent in the AI capabilities effort! I think any AI researcher who works on AI alignment at all, should sleep peacefully at night knowing they are a net positive (barring unpredictably bad luck). We shouldn't alienate these good people.

Yet I never manage to convince anyone on LessWrong of this!

PS: I admit there are some reasonable world models which disagree with me.

Some people argue that it's not a race between AI capabilities and AI alignment, but a race between AI capabilities and some mysterious time in the future when we manage to ban all AI development. They think this, because they think AI alignment is very impractical.

I think their world model is somewhat plausible-ish.

But first of all, if this was the case AI alignment work still might be an indirect net positive by moving the Overton window for taking AI x-risk seriously rather than laughing at it as a morbid curiosity. It's hard to make a dent in the hundreds of billions spent on AI capabilities, so the main effect of hundreds of millions spent on AI alignment research will still be normalizing a serious effort against AI x-risk. The US spending a lot on AI alignment is a costly signal to China, that AI x-risk is serious, and US negotiators aren't just using AI x-risk as an excuse to convince China to give up the AI race.

Second of all, if their world model was really correct, the Earth is probably already doomed. I don't see a realistic way to ban all AI development in every country in the near future. Even small AI labs like DeepSeek are making formidable AI, so there has to be an absurdly airtight global cooperation. We couldn't even stop North Korea from getting nukes, which was relatively far easier. In this case, the vast majority of all value in the universe would be found in ocean planets with a single island nation, where there would be no AI race between multiple countries (thus far far easier to ban AI). Planets like Earth (with many countries) would have a very low rate of survival, and be a tiny fraction of value in the universe.

My decision theory, is to care more about what to do in scenarios where what I do actually matter, and therefore I don't worry too much about this doomed scenario.

PS: I'm not 100% convinced Anthropic in particular is a net positive.

Their website only mentions their effort against AI x-risk among a pile of other self promoting corporate-speak, and while they are making many genuine efforts it's not obviously superior to other labs like Google DeepMind.

I find it confusing how many AI labs which seem to care enough about AI x-risk enough to be a net positive, are racing against each other rather than making some cooperative deal (e.g. Anthropic, Google DeepMind, SSI, and probably others I haven't heard about yet).

Wow we have a lot of the same thinking!

I've also felt like people who think we're doomed are basically spending a lot of their effort on sabotaging one of our best bets in the case that we are not doomed, with no clear path to victory in the case where they are correct (how would Anthropic slowing down lead to a global stop?)

And yeah I'm also concerned about competition between DeepMind/Anthropic/SSI/OpenAI - in theory they should all be aligned with each other but as far as I can see they aren't acting like it.

As an aside, I think the extreme pro-slowdown view is something of a vocal minority. I met some Pause AI organizers IRL and brought up the points I brought in my original comment, expecting pushback, but they agreed, saying they were focused on neutrally enforced slowdowns e.g. government action.

Yeah, I think arguably the biggest thing to judge AI labs on is whether they are pushing the government in favour of regulation or against. With businesses in general, the only way for businesses in a misregulated industry to do good, is to lobby in favour of better regulation (rather than against).

It's inefficient and outright futile for activists to demand individual businesses to unilaterally do the right thing, get outcompeted, go out of business, have to fire all their employees, and so much better if the activists focus on the government instead. Not only is it extraordinarily hard for one business to make this self sacrifice, but even if one does it, the problem will remain almost just as bad. This applies to every misregulated industry, but for AI in particular "doing the right thing" seems the most antithetical to commercial viability.

It's disappointing that I don't see Anthropic pushing the government extremely urgently on AI x-risk, whether it's regulation or even x-risk spending. I think at one point they even mentioned the importance of the US winning the AI race against China. But at least they're not against more regulation and seem more in favour of it than other AI labs? At least they're not openly downplaying the risk? It's hard to say.

DeepMind was funded by Jaan Tallinn and Peter Thiel

i did not participate in DM's first round (series A) -- my investment fund invested in series B and series C, and ended up with about 1% stake in the company. this sentence is therefore moderately misleading.

Thank you for pointing to this. Let me edit it to be more clear.

I see how it can read as if you and Peter were just the main guys funding DeepMind from the start, which of course is incorrect.

Edited:

DeepMind received its first major investment by Peter Thiel (introduced by Eliezer), and Jaan Tallinn later invested for a 1% stake.

Wow. There's a very "room where it happens" vibe about this post. Lots of consequential people mentioned, and showing up in the comments. And it's making me feel like...

Like, there was this discussion club online, ok? Full of people who seemed to talk about interesting things. So I started posting there too, did a little bit of math, got invited to one or two events. There was a bit of money floating around too. But I always stayed a bit at arms length, was a bit less sharp than the central folks, less smart, less jumping on opportunities.

And now that folks from the same circle essentially ended up doing this huge consequential thing - the whole AI thing I mean, not just Anthropic - and many got rich in the process... the main feeling in my mind isn't envy, but relief. That my being a bit dull, lazy and distant saved me from being part of something very ugly. This huge wheel of history crushing the human form, and I almost ended up pushing it along, but didn't.

Or as Mike Monteiro put it:

Tech, which has always made progress in astounding leaps and bounds, is just speedrunning the cycle faster than any industry we’ve seen before. It’s gone from good vibes, to a real thing, to unicorns, to let’s build the Torment Nexus in record time. All in my lifetime...

I was lucky (by which I mean old) to enter this field when I felt, for my own peculiar reasons, that it was at its most interesting. And as it went through each phase, it got less and less interesting to me, to the point where I have little desire to interact too much with it now... In fact, when I think about all the folks I used to work on web shit with and what they’re currently doing, the majority are now woodworkers, ceramicists, knitters, painters, writers, etc. People who make things tend to move on when there’s nothing left to make. Nothing to make but the Torment Nexus.

Oh, damn. I feel so... Sad. For everyone. For the people who they once were, before moloch ate their brains. For us, now staring into the maw of the monster. For the world.

Thanks for this.

A minor comment and a major one:

-

The nits: the section on the the Israeli military's use of AI against Hamas could use some tightening to avoid getting bogged down in the particularities of the Palestine situation. The line "some of the surveillance tactics Israeli settlers tested in Palestine" (my emphasis) to me suggests the interpretation that all Israelis are "settlers," which is not the conventional use of that term. The conventional use of settlers applied only to those Israelis living over the Green Line, and particularly those doing so with the ideological intent of expanding Israel's de facto borders. Similarly but separately, the discussion about Microsoft's response to me seemed to take as facts what I believe to still only be allegations.

-

The major comment: I feel you could go farther to connect the dots between the "enshittification" of Anthropic and the issues you raise about the potential of AI to help enshittify democratic regimes. The idea that there are "exogenously" good and bad guys, with the former being trustworthy to develop A(G)I and the latter being the ones "we" want to stop from winning the race, is really central to AI discourse. You've pointed out the pattern in which participating in the race turns the "good" guys into bad guys (or at least untrustworthy ones).

Thanks for the comments

The conventional use of settlers applied only to those Israelis living over the Green Line, and particularly those doing so with the ideological intent of expanding Israel's de facto borders.

Ah, I was actually trying to draw a distinction between Israeli citizens and those settling Palestinian regions specifically. Like I didn’t want to implicate Israelis generally. But I see how it’s not a good distinction because there are also soldiers and tech company employees testing surveillance tactics on Palestinians but living in Israel (the post-Nakba region).

Of course, I’m also just not much acquainted with how all these terms get used by people living in the regions. Thanks for the heads-up! I’ll try and see how to rewrite this to be more accurate.

the discussion about Microsoft's response to me seemed to take as facts what I believe to still only be allegations.

You’re right. I added it as a tiny sentence at the end. But what’s publicly established is that Microsoft supplied cloud services to the IDF while letting them just use that for what they wanted – not that the cloud services were used for storing tapped Palestinian calls specifically. I’ll add a footnote about this.

EDIT: after reading the Guardian article linked to from the one announcing Microsoft's inquiry, I think the second point is also pretty well-established: "But a cache of leaked Microsoft documents and interviews with 11 sources from the company and Israeli military intelligence reveals how Azure has been used by Unit 8200 to store this expansive archive of everyday Palestinian communications."

The major comment: I feel you could go farther to connect the dots between the "enshittification" of Anthropic and the issues you raise about the potential of AI to help enshittify democratic regimes.

This is a great insight. The honest answer is that I had not thought of connecting those dots here.

We see a race to the bottom to release AI to extract benefits in Anthropic’s founding researchers actions, and also in broader US society.

This is an excellent write-up. I'm pretty new to the AI safety space, and as I've been learning more (especially with regards to the key players involved), I have found myself wondering why more people do not view Dario with a more critical lens. As you detailed, it seems like he was one of the key engines behind scaling, and I wonder if AI progress would have advanced as quickly as it did if he had not championed it. I'm curious to know if you have any plans to write up an essay about OpenPhil and the funding landscape. I know you mentioned Holden's investments into Anthropic, but another thing I've noticed as a newcomer is just how many safety organization OpenPhil has helped to fund. Anecdotally, I have heard a few people in the community complain that they feel that OpenPhil has made it more difficult to publicly advocate for AI safety policies because they are afraid of how it might negatively affect Anthropic.

Glad it's insightful.

I'm curious to know if you have any plans to write up an essay about OpenPhil and the funding landscape.

It would be cool for some to write about how the funding landscape is skewed. Basically, most of the money has gone into trying to make safe the increasingly complex and unscoped AI developments that people are seeing or expecting to happen anyway.

In the last years, there has finally been some funding of groups that actively try to coordinate with an already concerned public to restrict unsafe developments (especially SFF grants funded by Jaan Tallinn). However, people in the OpenPhil network especially have continued to prioritise working with AGI development companies and national security interests, and it's concerning how this tends to involve making compromises that support a continued race to the bottom.

Anecdotally, I have heard a few people in the community complain that they feel that OpenPhil has made it more difficult to publicly advocate for AI safety policies because they are afraid of how it might negatively affect Anthropic.

I'd be curious for any ways that OpenPhil has specifically made it harder to publicly advocate for AI safety policies. Does anyone have any specific experiences / cases they want to share here?

Wait, why did this get moved to personal blog?

Just surprised because this is actually a long essay I tried to carefully argue through. And the topic is something we can be rational about.

I was unsure about it, the criteria for frontpage are "Timeless" (which I agree this qualifies as) and "not inside baseball-y" (often with vaguely political undertones), which seemed less obvious. My decision at the the time was "strong upvote but personal blog", but I think it's not obvious and if another LW mod. I agree it's a bunch of good information to have in one place.

Thanks for sharing openly. I want to respect your choice here as moderator.

Given that you think this was not obvious, could you maybe take another moment to consider?

This seems a topic that is actually important to discuss. I have tried to focus as much as possible on arguing based on background information.

I see it is now on the frontpage. Just want to share my appreciation for how you've handled this. Also if you had kept it on the personal blog, I would have still appreciated the openness about your decision.

(Another mod leaned in the other direction, and I do think there's like, this is is pretty factual and timeless, and Dario is more of a public figure than an inside-baseball lesswrong community member, so, seemed okay to err in the other direction. But still flagging it as an edge case for people trying to intuit the rules)

Title is confusing and maybe misleading, when I see "accelerationists" I think either e/acc or the idea that we should hasten the collapse of society in order to bring about a communist, white supremacist, or other extremist utopia. This is different from accelerating AI progress and, as far as I know, not the motivation of most people at Anthropic.

I get that seeing “accelerationists” gives that that association.

I wrote moderate accelerationists to try and make the distinction. I’m not saying that Dario’s circle of researchers who scaled up GPT were gung-ho in their intentions to scale like many e/acc people are. They obviously had safety concerns and tried to delay releases, etc.

I’m just saying they acted as moderate accelerationists.

The title is not perfect, but got to make a decision here. Hope you understand.

I have a better idea now what you intend. At risk of violating the "Not worth getting into?" react, I still don't think the title is as informative as it could be; summarizing on the object level would be clearer than saying their actions were similar to actions of "moderate accelerationists", which isn't a term you define in the post or try to clarify the connotations of.

Who is a "moderate communist"? Hu Jintao, who ran the CCP but in a state capitalism way? Zohran Mamdani, because democratic socialism is sort of halfway to communism? It's an inherently vague term until defined, and so is "moderate accelerationists".

I would be fine with the title if you explained it somewhere, with a sentence in the intro and/or conclusion like "Anthropic have disappointingly acted as 'moderate accelerationists' who put at least as much resource into accelerating the development of AGI as ensuring it is safe", or whatever version of this you endorse. As it is some readers, or at least I, have to think

- does Remmelt think that Anthropic's actions would also be taken by people who believe extinction by entropy-maximizing robots is only sort of bad?

- Or is it that Remmelt thinks that Anthropic is acting like a company who think the social benefits of speeding up AI could outweigh the costs?

- Or is the post trying to claim that ~half of Anthropic's actions sped up AI against their informal commitments?

This kind of triply recursive intention guessing is why I think the existing title is confusing.

Alternatively, the title could be something different like "Anthropic founders sped AI and abandoned many safety commitments" or even "Anthropic was not consistently candid about its priorities". In any case it's not clear to me that it's worth changing vs making some kind of minor clarification.

Thanks, you're right that I left that undefined. I edited the introduction. How does this read to you?

"From the get-go, these researchers acted in effect as moderate accelerationists. They picked courses of action that significantly sped up and/or locked in AI developments, while offering flawed rationales of improving safety."

"acted as" vs "intended" seems to me to be the distinction here. There's a phrase that was common a few years back which I still like: intent isn't magic.

Despite the shift, 80,000 Hours continues to recommend talented engineers to join Anthropic.

FWIW, it looks to me like they restrict their linked roles to things that are vaguely related to safety or alignment. (I think that the 80,000 Hours job board does include some roles that don't have a plausible mechanism for improving AI outcomes except via the route of making Anthropic more powerful, e.g. the alignment fine-tuning role.)