I think that movies are getting longer.

I didn't check this systematically, but it feels like old movies are about 80 minutes long, and the recent ones are approaching 120 minutes.

This could just be a function of film directors getting better at making long films with pacing that keeps lower attention spans engaged.

This again seems like something that different people could interpret differently.

I usually watch movies on my computer, and when I think they are too slow, I increase the speed. (If I no longer understand the speech at the high speed, I add subtitles.) Recently, I usually watch a movie on 2x speed, and slow down if there is some action scene or a nontrivial dialogue. Speed up if too boring.

Seems to me that most (but not all) movies follow the same pacing, where during the first half of the movie almost nothing happened, we just get the protagonist introduced. Then things start happening, then they get more dramatic, then there is the climax, then a short cool down and the movie ends.

Now, is this "pacing that keeps lower attention spans engaged"? For me, the first half of such movie is the one that watch at 2x or 3x speed, and if I didn't have an option to do that or to skip that part, I probably would not have watched many of the movies (so I would never learn that the second half was good).

I suspect the desired psychological outcome is more like: "people remember the end of the movie most, so let's push everything interesting as close to the end as possible". And a possible bet that if they are in a cinema (where the producent probably gets most money), people won't leave during the first half.

With old movies, the pacing seems more like the slow and fast sections alternate throughout the film.

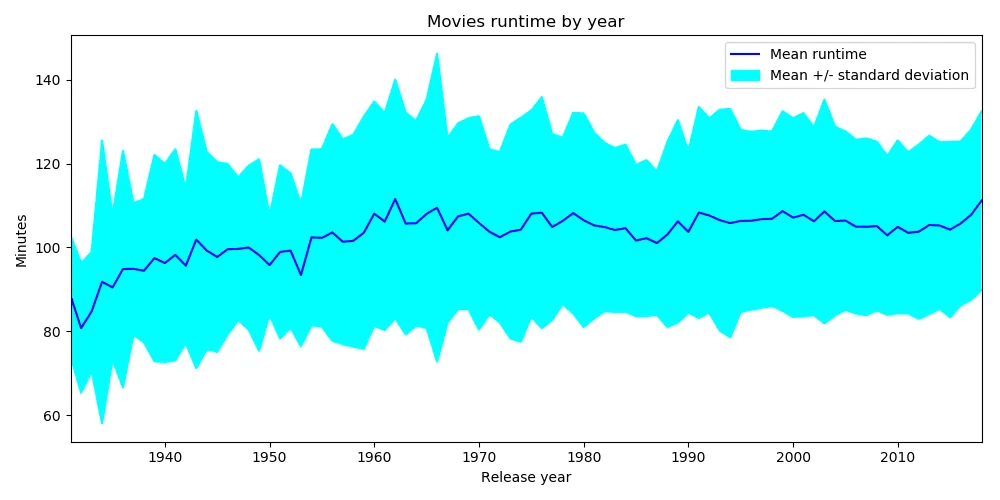

I looks like movies have been getting longer:

Although there seems to have been a slight dip/stagnation in the 2000s and 2010s, and the text concludes with

In conclusion, our intuition was wrong. There is no trend in the movies runtime. The differences are too small to be noticed. We can say that for the last 60 years movies on average have the same length. No matter what criteria we take into account, the result is the same.

Interesting. The graph seems to fit Viliam's intuition rather well. It is a noisy dataset (not to mention that "movie" is probably a poorly defined item so might have both apples and oranges here) so I'm not quite sure one can easily make the claim of increasing or constant very easily.

You might find some of the discussion here of interest on the subject. This listing of John Wayne movies, with run time listed might also be of interest.

I have been under the impression that they had been getting shorter - say from the 70s to the 90s/00s but then started lengthening again a bit somewhat after that until now. Nothing very scientific about my recollection of that observation though.

I always assumed this was a shift due to VCRs, DVDs, and then DVRs and streaming. Today media can assume everyone can watch anything as often as they want. Older media had to assume no one would ever watch it more than once, or be able to look up anything they missed. Old movies and TV shows are simple in the stories they tell, simpler in dialog, and shorter in length, so you can mostly catch everything the first time through.

Movies in general require very little attention compared to just listening or even reading. Since they are audiovisual, they leave very little to the imagination. So I expect other influences have a larger effect.

TL;DR: I still really like this text, but am unhappy I didn't update it/work on it in the last year. There's now research on the exact topic, finding attention spans have plausibly increased in adults.

Out of the texts I wrote in 2023, this one is my favorite: I had a question, tried to figure out the truth, saw that there was no easy answer and then dug deeper into the literature, producing the (at the time) state-of-the-art investigation into attention spans—sometimes often answered questions haven't been actually checked, yet everyone spouts nonsense about them anyway. I'm happy this one got nominated, I like been positively reinforced for writing high-effort factposts.

The post was linked in a bunch of places: First on HN, where it occupied the top spot for a while, and later on mastodon, Stack Exchange Academia Meta, metafilter, HN comments, here on LW and a few blogposts. Multiple places link it just for one of the pictures :-). (I've also linked this post whenever someone made any claim about attention spans. Fun.)

Looking through the texts linking to this one (found with the backlink checker) I think my biggest mistake was not explaining the subscript probability in the abstract—it's very often misread as attention spans declining by 65%, not that I believe that attention spans have been declining with a probability of 65%.

I'm also not super happy about the middle section: I wrote it first while going through papers, and it could be cleaned up a bit to be more readable. I didn't run any of the experiments proposed in the later sections, and now I don't have to: Andrzejewski et al. 2024 (h/t Marginal Revolution via Zvi) performed a meta-analysis very similar to the one outlined in option 3 in this section[1] with the d2 test[2], finding gains on attention span in adults over the last 30 years, and some worsening in children.

I have some wild guesses what this means, but didn't predict an increase in attention spans. Maybe some Flynn-like-but-not-measured-by-IQ-tests gains in cognitive performance are still happening due to improved nutrition or less pollution, but children are more affected by a attention-sapping environment; or there is some amount of immunization or habituation happens to people in a distracting environment, but they have to go through that as children first; or there is some selection effect in the papers for the meta-analysis (I haven't read it in that great amount of detail).

In the future, I would personally like to read Andrzejewski et al. carefully & work them into the text, as well as try and find some more work done in the meantime. I likely won't find the time, but if I did I'd want to replicate their meta-analysis with the TOVA or the continuous performance task.

It is a bit crazy that was ahead of academia by about one year in noticing the discrepancy of research on this topic and producing a then-state-of-the-art investigation on it—a topic many people were talking about at the time! (And continue to talk about.) Another nail in the coffin for Cowen's 2nd law.

Especially after reading the paper, I've become slightly less worried about declining attention spans, but not enough to let down my defenses against the onslaught of internet grabbiness. At the time I was writing the text I was quite worried about AI systems posing immediate & under-rated danger through distracting/addicting/convincing people in difficult-to-notice and hard-to-avoid ways, that has taken a bit longer than I expected. I wasn't worried about deepfakes or political polarization as much as more subliminal & unintended-by-the-developers hacking of human minds by AIs. This is now finally starting to happen, but more covertly than I guessed it'd look like in 2022.

Finally, I liked the comment section on this post, especially the comment by Viliam about movies increasing in length.

Since this is my own post, I can't vote on it, but I'm happy where it's at, and just the fact it got nominated means I'll update & edit it—it's rough in a couple of places, especially the middle.

Indeed, their method is so similar to the one I propose that I'm tempted to speculate they did the analysis after reading my post—probably not true, but a fun option. ↩︎

I vaguely remember seeing that Wikipedia article, but I'm unhappy I didn't include it in the text as one possible measure of attention span. ↩︎

Thank you for this! Strong-upvoted.

I only skimmed, so maybe you discuss this and I missed it, my apologies if so -- what about a metric that logs screen time over the course of a day, and tracks frequency of major task shift? E.g. we could classify websites as "work-related" or "entertainment" or "other" and then track how many shifts from work-related to entertainment happen throughout the day. If we had been tracking this for 20 years then maybe we'd have some good data on pretty much exactly the problem I'm most concerned about when I say attention spans seem to be declining...

Mark 2023 looks at this, I've summarized the relevant stuff at the end of this section, and the time spent per task has indeed been declining. I don't know about research looking at task classification, but that would be interesting to do.

My current take is that this provides medium evidence—but I think this could also be evidence of higher ability at priorization.

Better at getting specific information out of a present piece of information (e.g. becoming skilled at skimming), better at putting tasks aside when they need some time to be processed in the background.

I would buy that hypothesis if the data was less time between switches within work-related tasks, but if the pattern is more frequent visits to entertainment sites during work hours, that sure doesn't sound like a good thing to me. Yeah maybe it's wisely letting stuff process in the background while I browse reddit or less wrong, but very likely it just is what it appears to be- degraded attention span and/or I creased internet addiction.

I found this comment both unhelpful and anti-scholarship, and have therefore strong - downvoted.

Np! I actually did read it and thought it was high-quality and useful. Thanks for investigating this question :)

Regarding your study idea. Sounds good! Would be interesting to see, and as you rightly point out wouldn't be too complicated/expensive to run. It's generally a challenge to run multi-year studies of this sort due to the short-term nature of many grants/positions. But certainly not impossible.

An issue that you might have is being able to be sure that any variation that you see is due to changes in the general population vs changes in the sample population. This is an especially valid issue with MTurk because the workers are doing boring exercises for money for extended periods of time, and many of them will be second screening media etc. A better sample might be university students, who researchers fortunately do have easy access to.

Strong upvoted. I've recently been interested in whether you could consider transformative slow takeoff to have started ~5-10 years ago via the deep learning revolution. I don't know whether it would have much of an effect on the number of highly-skilled AI capabilities researchers, but the effect would be so broad that it would nonetheless be significant for global forecasting in tons of other ways. Unless, of course, meditation becomes popular extremely popular or social media platforms change their algorithm policies, immediately reversing the trend. The impression that I get from current social media news feed/scrolling systems is that they have many degrees of freedom to measure changes over time, and perhaps even adjust user's attention spans in aggregate.

With systems like TikTok-based platforms, the extreme gratification offered would require substantial evidence to prove that attention spans haven't been shortening, given neuroplasticity. It's theoretically plausible, but not where I'd bet, even before reading this.

I investigate whether the attention span of individual humans has been falling over the last two decades (prompted by curiosity about whether the introduction of the internet may be harmful to cognitive performance). I find little direct work on the topic, despite its wide appeal. Reviewing related research indicates that individual attention spans might indeed have been declining65%.

Have Attention Spans Been Declining?

In what might be just the age-old regular ephebiphobia, claims have been raised that individual attention spans have been declining—not just among adolescents, but among the general population. If so, this would be quite worrying: Much of the economy in industrialized societies is comprised of knowledge work, and knowledge work depends on attention to the task at hand: switching between tasks too often might prevent progress on complicated and difficult problems.

I became interested in the topic after seeing several claims that e.g. Generation Z allegedly has lower attention spans and that clickbait has disastrous impacts on civilizational sanity, observing myself and how I struggled to get any work done when connected to the internet, and hearing reports from others online and in person having the same problem. I was finally convinced to actually investigate™ the topic after making a comment on LessWrong asking the question and receiving a surprisingly large amount of upvotes.

The exact question being asked is:

"Have the attention spans of individuals on neutral tasks (that is, tasks that are not specifically intended to be stimulating) declined from 2000 to the present?"

(One might also formulate it as "Is there an equivalent of the “Reversed Flynn Effect” for attention span?") I am not particularly wedded to the specific timeframe, though the worries mentioned above assert that this has become most stark during the last decade or so, attributing the change to widespread social media/smartphone/internet usage. Data from before 2000 or just the aughts would be less interesting. The near-global COVID-19 lockdows could provide an especially enlightening natural experiment: Did social media usage increase (my guess: yes90%), and if so, did attention spans decrease at the same time (or with a lag) (my guess: also yes75%), but I don't think anyone has the data on that and wants to share it.

Ideally want to have experiments from ~2000 up to 2019: close enough to the present to see whether there is a downward trend (a bit more than a decade after the introduction of the iPhone in 2007), but before the COVID-19 pandemic which might be a huge confounder, or just have accelerated existing trends (which we can probably check in another 2 years).

I am mostly interested in the attention span of individual humans and not groups: Lorenz-Spreen et al. 2019 investigate the development of a construct they call "collective attention" (and indeed find a decline), but that seems less economically relevant than individual attention span. I am also far less interested in self-perception of attention span, give me data from a proper power- or speed-test, cowards!

So the question I am asking is not any of the following:

How Is Attention Span Defined?

Attention is generally divided into three distinct categories: sustained attention, which is the consistent focus on a specific task or piece of information over time (Wikipedia states that the span for sustained attention has a leprechaun figure of 10 minutes floating around, elaborated on in Wilson & Korn 2007); selective attention, which is the ability to resist distractions while focusing on important information while performing on a task (the thing trained during mindfulness meditation); and alternating or divided attention, also known as the ability to multitask.

When asking the question "have attention spans been declining", we'd ideally want the same test measuring all those three aspects of attention (and not just asking people about their perception via surveys), performed anually on large random samples of humans over decades, ideally with additional information such as age, sex, intelligence (or alternatively educational attainment), occupation etc. I'm personally most interested in the development of sustained attention, and less so in the development of selective attention. But I have not been able to find such research, and in fact there is apparently no agreed upon test for measuring attention span in the first place:

— Simon Maybin quoting Dr. Gemma Briggs, “Busting the attention span myth”, 2017

So, similar to comas, attention span doesn't exist…sure, [super-proton things come in varieties](https://unremediatedgender.space/2019/Dec/on-the-argumentative-form-super-proton-things-tend-to-come-in-varieties/index.html "On the Argumentative Form "Super-Proton Things Tend to Come In Varieties"), but which varieties?? And how??? Goddamn, psychologists, do your job and don't just worship complexity.

Perhaps I should soften my tone, as this perspective appears elsewhere:

— Plude et al., “The development of selective attention: A life-span overview” p. 31, 1994

How Do We Measure Attention Span?

One of my hopes was that there is a canonical and well-established (and therefore, ah, tested) test for attention span (or just attention) à la the IQ test for g: If so, I would be able to laboriously go through the literature on attention, extract the individual measurements (and maybe even acquire some datasets) and perform a meta-analysis.

Continuous Performance Tests

For measuring sustained and selective attention, I found the family of continuous performance tests, including the Visual and Auditory CPT (IVA-2), the Test of Variables of Attention (T.O.V.A.), Conners' CPT-III, the gradCPT and the QbTest, some of which are described here. These tests usually contain two parts: a part with low stimulation and rare changes of stimuli, which tests for lack of attention, and a part with high stimulation and numerous changes of stimuli, which tests for impulsivity/self control.

Those tests usually report four different scores:

I'm currently unsure about two crucial points:

Other Heterogenous Metrics

I also attempted to find a survey or review paper on attention span, but was unsuccessful in my quest, so I fell back to collecting metrics for attention span from different papers:

As it stands, I think there's a decent chance60% that one or several tests from the CPT family can be used as tests for attention span without much of a problem.

I don't think a separate dedicated test for attention span exists45%: The set of listed measures I found (apart from the CPT) appears to be too heterogenous, idiosyncratic, mostly not quantitative enough and measuring slightly different things to be robustly useful for a meta-analysis.

What Are the Existing Investigations?

—Bobby Duffy & Marion Thain, “Do we have your attention” p. 5, 2022

—Carstens et al., “Social Media Impact on Attention Span” p. 2, 2018

—Carstens et al., “Social Media Impact on Attention Span” p. 3, 2018

Mark 2023 is a recent book about attention spans, which I was excited to read and find the important studies I'd missed. Unfortunately, it is quite thin on talking about the development of attention span over time. It states that

—Gloria Mark, “Attention Span” p. 13/14, 2023

which is not quite strong enough a measurement for me.

—Gloria Mark, “Attention Span” p. 74/75, 2023

She doesn't mention the hypothesis that this could be the symptom of a higher ability to prioritize tasks, although she is adamant that multi-tasking is bad.

Furthermore, this behavior displays only a decrease in the propensity of attention, but not necessarily one of capacity: Perhaps people could concentrate more, if they wanted to/were incentivized to, but they don't, because there is no strong intent to or reward for doing so. Admittedly, this is less of an argument in the workplace where these studies were conducted, but perhaps people just care not as much about their jobs (or so I've heard).

—Gloria Mark, “Attention Span” p. 97, 2023

She gives some useful statistics about time spent on screens:

—Gloria Mark, “Attention Span” p. 180, 2023

She connects attention span to shot-length in movies:

—Gloria Mark, “Attention Span” p. 180/181, 2023

—Gloria Mark, “Attention Span” p. 189, 2023

Do People Believe Attention Spans Have Declined?

—Bobby Duffy & Marion Thain, “Do we have your attention” p. 6, 2022

—Bobby Duffy & Marion Thain, “Do we have your attention” p. 7, 2022

Note that selective attention mostly improves with age, so the older age-groups might be comparing themselves now to the younger age groups now (as opposed to remembering back at their own attention spans).

—Bobby Duffy & Marion Thain, “Do we have your attention” p. 18, 2022

In response to the questions (n=2093 UK adults aged 18+ in 2021):

What About Rates of ADHD?

Data from the CDC shows a clear increase in the percentage of children with a parent-reported ADHD diagnosis:

There has been a similar increase in the diagnosis of ADHD among adults, "from 0.43 to 0.96 percent" between 2007 and 2016.

However, this does not necessarily mean that the rate of ADHD has increased, if e.g. awareness of ADHD has increased and therefore leads to more diagnoses.

What Could A Study Look Like?

Compared to other feats that psychology is accomplishing, finding out whether individual attention spans are declining appears to be of medium difficulty, so I'll try to outline how this could be accomplished in three different ways:

Conclusion

Given the amount of interest the question about shrinking attention spans has received, I was surprised to not find a knockdown study of the type I was looking for, and instead many different investigations that were either not quite answering the question I was asking or too shoddy (or murky) to be trusted. I seems likely to me that individual attention spans have declined (I'd give it ~70%), but I wouldn't be surprised if the decline was relatively small, noisy & dependent on specific tests.

So—why hasn't anyone investigated this question to satisfaction yet? After all, it doesn't seem to me to be extremely difficult to do (compared to other things science has accomplished), there is pretty clearly a lot of media attention on the question (so much so that a likely incorrect number proliferates far & wide), it appears economically and strategically relevant to me (especially sustained attention is probably an important factor in knowledge work, I'd guess?) and it slots more or less into cognitive psychology.

I'm not sure why this hasn't happened yet (and consider it evidence for a partial violation of Cowen's 2nd law—although, to be fair, the law doesn't specify there needs to be a good literature on everything…). The reasons I can think of is that one would need to first develop a good test for determining attention span, which is some work in itself (or use the CPT); be relatively patient (since the test would need to be re-run at least twice with a >1 year pause, for which the best grant structure might not exist); there are many partial investigations into the topic, making it appear like it's solved; and perhaps there just aren't enough cognitive psychologists around to investigate all the interesting questions that come up.

So I want to end with a call to action: If you have the capacity to study this problem, there is room for improvement in the existing literature! Attention spans could be important, it's probably not hard to measure them, and many people claim that they're declining, but are way too confident about it given the state of the evidence. False numbers are widely circulated, meaning that correct numbers might be cited even more widely. And it's probably not even (that) hard!

Consider your incentives :-).

Appendix A: Claims That Attention Spans Have Been Declining

Most of these are either unsourced or cite Gausby 2015 fallaciously (which Bradbury 2016 conjectures to be the number of seconds spent on websites on average).

—Carstens et al., “Social Media Impact on Attention Span” p. 2, 2018

—Leong et al., “A review of the trend of microlearning” p. 2, 2020

—Sandee LaMotte, “Your attention span is shrinking, studies say. Here's how to stay focused”, 2023

—Zia Muhammad, “Research Indicates That Attention Spans Are Shortening”, 2020

—EU Business School, “The Truth about Decreasing Attention Spans in University Students”, 2022

(No link given.)

—Neil A. Bradbury, “Attention span during lectures: 8 seconds, 10 minutes, or more?”, 2016

Appendix B: Studies for a Meta-Analysis

I'll list the closest thing those studies have to a control group, list sorted by year.

Studies using the CPT

Furthermore, “Is the Continuous Performance Task a Valuable Research Tool for use with Children with Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder” (Linda S. Siegel/Penny V. Corkum, 1993) p. 8-9 contains references to several studies from before 1993 using the CPT on children with ADHD.

Appendix C: How I Believed One Might Measure Attention Span Before I Found Out About The CPT

Before I found out about the Continuous Performance Test, I speculated about how to measure attention span:

(Note that I'm not a psychometrician, but I like speculating about things, so the ideas below might contain subtle and glaring mistakes. Noting them down here anyway because I might want to implement them at some point.)

It seems relatively easy to measure attention span with a power- or speed-test, via one of three methods:

t_change), and the time between the change of the stimulus and the reporting of the change (calling this valuet_report). Performing this test with different value oft_changeshould result in different values oft_report. There is at_changefor whicht_reportfalls over a threshold value, thatt_changecan be called the attention span.t_changefor whicht_reportfalls over the threshold value.Such an instrument would of course need to have different forms of reliability and validity, and I think it would probably work best as a power test or a speed test.

I'm not sure how such a test would relate to standard IQ tests: would it simply measure a subpart of g, completely independent or just partially related to it?