outside view: thinking about advanced AI as another instance of a highly advanced and impactful technology like the internet, nuclear energy, or biotechnology.

I strongly disagree with this -- you are simply picking a particular reference class (no not even that, a particular analogy) and labelling it the outside view. See this post for more.

Thank's for pointing that out and for the linked post!

I'd say the conclusion is probably the weakest part of the post because after describing the IABIED view and the book's critics I found it hard to reconcile the two views.

I tried getting Gemini to write the conclusion but what it produced seemed even worse: it suggested that we treat AI like any other technology (e.g. cars, electricity) where doomsday forecasts are usually wrong and the technology can be made safe in an iterative way which seems too optimistic to me.

I think my conclusion was an attempt to find a middle ground between the authors of IABIED and the critics by treating AI as a risky but not world-ending technology.

(I'm still not sure what the conclusion should be)

I think the level of disagreement among the experts implies that there is quite a lot of uncertainty so the key question is how to steer the future toward better outcomes while reasoning and acting under substantial uncertainty.

The framing I currently like best is from Chris Olah’s thread on probability mass over difficulty levels.

The idea is that you have initial uncertainty and a distribution that assigns probability mass to different levels of alignment difficulty.

The goal is to develop new alignment techniques that "eat marginal probability" where over time the most effective alignment and safety techniques can handle the optimistic easy cases, and then the medium and hard cases and so on. I also think the right approach is to think in terms of which actions would have positive expected value and be beneficial across a range of different possible scenarios.

Meanwhile the goal should be to acquire new evidence that would help reduce uncertainty and concentrate probability mass on specific possibilities. I think the best way to do this is to use the scientific method to proposed hypotheses and then test them experimentally.

Here are some reasons why an outer optimizer may produce an AI that has a misaligned inner objective according to the paper Risks from Learned Optimization in Advanced Machine Learning Systems:

- Unidentifiability: ...

- Simplicity bias: ...

My main reason for expecting misaligned inner objectives isn’t quite captured by either of these. Outside of toy situations, it’s rare in modern ML training for the solution with the lowest loss on the training data to actually be underdetermined in a meaningful sense. Rather, the main issue is that the data is almost always full of tiny systematic effects that we don’t understand or even know about. As a result, the inner objective an ML engineer might imagine would score the lowest loss when they set up their training environment will probably not, in fact, be the inner objective that actually does so. In other words, the problem isn't that the best-scoring inner objective is genuinely underdetermined in the training loss landscape; it’s that it’s underdetermined to current-day human engineers, with very imperfect knowledge of the data and the training dynamics it induces, who are trying to intuit the answer in advance.

For example, an inner objective shaped around human-like empathy might turn out to make the AI spend an average 0.03% inference steps extra on worrying about whether the human overseers think it is a virtuous member of the tribe while it’s supposed to be solving math problems. That inner objective then loses out to some weird, different objective that’s slightly more compatible with being utterly focused while crunching through ten million calculus problems in a row without any other kind of sensory input.

For a non-fictional current-day example, a lot of RLHF data turned out to reward agreeableness more than sincerity to an extent most MI engineers apparently did not anticipate, leading to a wave of sycophantic models.

This problem gets worse as AI training become more dominated by long-form RL environments with a lot of freedom for the AIs to do unexpected stuff, and as the AIs become more creative and agentic. An ML engineer trying to predict in advance which losses and datasets will favor AIs with inner objectives they like over ones they don’t like has a harder and harder time simulating in their head in advance how those AIs might score on the training loss, because it is becoming less and less easy to guess what behaviors those objectives would actually lead to.

Thanks for the detailed comment.

Outside of toy situations, it’s rare in modern ML training for the solution with the lowest loss on the training data to actually be underdetermined in a meaningful sense.

Would you mind elaborating on what you mean by this? My guess is that you're saying that in a real-world situation with sufficiently diverse data and enough training, catastrophic misgeneralization or overfitting like the CoinRun example in the post is rare.

Though there is also the problem of adversarial examples (e.g. jailbreaks) where the model performs okay on normal test distribution data but poorly on OOD examples that are designed to trick the model.

No, that is not what I am saying. I am saying that the typical reason these sorts of "misgeneralizations" happen is not that there are many parameter configurations on the neural network architecture that all get the same training loss, but extrapolate very differently to new data. It's that some parameter configurations that do not extrapolate to new data in the way the ml engineers want straight up get better loss on the training data than parameter configurations that do extrapolate to new data in the way the ml engineers want.

I don't think "overfitting" is really the right frame for what's going on here. This isn't a problem with neural networks having bad simplicity priors and choosing solutions that are more algorithmically complex than they need to be. Modern neural networks have pretty good simplicity priors. I don't expect misaligned AIs to have larger effective parameter counts than aligned AIs. The problem isn't that they overfit, the problem is that the algorithmically simplest fit to the training environment that scores the lowest loss often just doesn't actually have the internal properties the ml engineers hoped it would have when they set up that training environment.

What's puzzling is how two highly intelligent people can live in the same world but come to radically different conclusions: some people (such as the authors) view an existential catastrophe from AI as a near-certainty, while others see it as a remote possibility (many of the critics).

In college I majored in philosophy, and in high school I participated in political debates. I learned early on that this sad state of affairs (radical persistent disagreement among smart knowledgeable good-faith experts) is the norm in human discourse rather than the exception.

Yeah that's probably true and it reminds me of Plank's principle. Thanks for sharing your experience.

I like to think that this doesn't apply to me and that I would change my mind and adopt a certain view if a particularly strong argument or piece of evidence supporting that view came along.

It's about having a scout mindset and not a soldier mindset: changing your mind is not defeat, it's a way of getting closer to the truth.

I like this recent tweet from Sahil Bloom:

I’m increasingly convinced that the willingness to change your mind is the ultimate sign of intelligence. The most impressive people I know change their minds often in response to new information. It’s like a software update. The goal isn't to be right. It's to find the truth.

The book Superforecasting also has as similar idea: the best superforecasters are really good and constantly updating based on new information:

The strongest predictor of rising into the ranks of superforecasters is perpetual beta, the degree to which one is committed to belief updating and self-improvement. It is roughly three times as powerful a predictor as its closest rival, intelligence.

Curated. This is a clearly written, succinct version of both arguments and counterarguments, which doesn't even seem terribly lossy to me (though I've read IABIED in full but not the counterarguments). I find it helpful for loading it all up into my mental context at once, and helpful for directing my own thinking for further investigation. All that to say, I think this post does the world a good service. And like much distillation work, deserves more appreciation than is the default.

I'm pretty on the doomy side and find the counterarguments not persuasive, but it is interesting to realize that often that's because of yet further arguments/counter-counter arguments that I'm aware of but aren't in IABIED itself, if I'm remembering correctly, or at least not at the length or depth I think is warranted for how intuitively reasonable those counterarguments seem, e.g. that models are trained on lots of data about human values and so hitting that target wouldn't so surprising after all, and how current models seem pretty aligned. I think answering them requires something of a 201 of IABIED. (But that's why we have the Four Layers of Intellectual Conversation!)

However, I am saddened that this review is missing the critiques that I'm most interested in hearing, e.g. those from the likes of Buck and Ryan, e.g. I enjoyed most of IABIED. The counterargument authors like Matthew Barnett, Quintin, Nora, etc are people with whom I have a lot of divergences of views, so their arguments have a harder time for being compelling. Buck and Ryan are much, much closer (and I respect their thinking) such that I'd like any list to capture their arguments (or at least link to them). Notwithstanding, I like this piece. Kudos!

Thanks for writing this summary, I think it's the best summary of the core arguments and best counterarguments by critics that I've seen. (though I haven't done an exhaustive search or anything)

Yes, I agree [1]. At first, I didn't consider writing this post because I assumed someone else would write a post like it first. The goal was to write a thorough summary of the book's arguments and then analyze them and the counterarguments in a rigorous and unbiased way. I didn't find a review that did this so I wrote this post.

Usually a book review just needs to give a brief summary so that readers can decide whether or not they are interested in reading the book and there are a few IABIED book reviews like this.

But this post is more like an analysis of the arguments and counterarguments than a book review. I wanted a post like this because the book's arguments have really high stakes and it seems like the right thing to do for a third party to review and analyze the arguments in a rigorous and high-quality way.

- ^

Though I may be biased.

Human values are not a fragile, tiny target, but a "natural abstraction" that intelligence tends to converge on.

My humble opinion is: this claim is probably right, and nevertheless the IABIED thesis is probably also right.

What we are actually hoping for with ASI is much, much harder to get than an ASI that has human values. Humans are animals seeking control and power, putting ourselves above any other beings in our environment. We don't want ASI to be seeking control and power, putting itself above any other beings in its environment (which would be the "natural abstraction that intelligence tends to converge on"). We want ASI to selflessly care about the long-term flourishing of humanity, forever and ever. And this certainly is "a fragile, tiny target". As opposed to power-seeking, this does not naturally follow from instrumental convergence.

I strongly agree with and support this comment. It seems rather unfortunate how frequently people fail to distinguish between "human values", "humanity's values", "human friendly values", and "humanity friendly values", each of which seem very importantly distinct from one another, and only the last seems like a worthy goal for ASI.

My humble opinion is: this claim is probably right, and nevertheless the IABIED thesis is probably also right.

This claims seems contradictory because part of the IABIED view is that human values are unlikely to be internalized in an ASI's preferences. Though it's true if you are defining the "IABIED thesis" as simply "ASI is likely to cause human extinction".

In my opinion, the IABIED thesis is not just that ASI is an extinction risk, but also the claim that this would occur because of the ASI ending up with alien values misaligned with human survival. In other words, it's a specific argument about the nature of AI training and AI value construction that leads to human extinction.

These two claims are different:

- This seems to be the view you are describing: AI is an extinction risk because it will imitate the worst of human values.

- This is the actual IABIED view in my opinion: AI is an extinction risk because it would have unpredictable alien values that are indifferent to human survival.

I think we essentially agree. The only difference seems to be with the word "alien" in "AI is an extinction risk because it would have unpredictable alien values that are indifferent to human survival". In my opinion, they may be alien, but more likely they may also be the familiar power-oriented values implied by instrumental convergence, which also coincidentally constitute an important subset of "human values".

I would argue that more focus is warranted on values as being emergent, independent of whether they are in the training data in some form. The right to live for instance feels very fundamental morally, but it can also be seen as a necessary means for effective cooperation amongst individuals and thus something that will emerge in sufficiently advanced societies of a certain type. The term to put this under would be moral convergent evolution.

It's not a given that in ASI such a value would emerge as it would be pretty dissimilar to a human. Nevertheless I think it would be very interesting to try to analyze which values seem more probable to emerge in AGI and ASI coming to life among us. Again, (mostly) independent of training data, but just based on evolutionary attractiveness.

Thank you for this—I think it does a great job of its objective.

Reading this reinforces my sense that while plenty of people have put forth some thoughtful and insightful disagreements with IABIED, there's no comprehensive counter-argument that has anywhere near the level of polish and presentation as IABIED itself.

I appreciate your taking on the core issues and summarizing them. Bravo! Being paywalled, the material is not freely available in general.

You tried to enumerate all views but did not list quite the perspective I had: I think we can take solace from previous encounters between vast intelligence differences, for examples mushrooms versus people. This is a variant of "alignment is not hard" that is more like "sufficient alignment is not hard". The "sufficient" part is very important. I completely agree with the IABIED perspective that AI alignment is hard, but all we need for survival is that the extreme worst anti-alignment does not come to pass.

So let's look at mushrooms for a minute and come back to AI.

Mushrooms came first. Mushrooms, if we include fungi in general, go back over a billion years. Humanity goes back less than a million. Humans have dominated mushrooms in most categories and certainly in anything involving intelligence, but we've lived on earth together just fine and barely even notice each other are there.

I take some solice that this kind of thing happens all the time. A difference in capability does not generally lead to all-out war with no peace possible.

We know that this is true just from considering the evidence. Why it happens is a more speculative question, but here are two reasonsthat seem plausible to me:

1. To the extent that values are in the same plane as each other, it is often better to cooperate than to fight, even from a selfish point of view. Mushrooms and humans do both want food and sunlight. However, people are not wiping out mushrooms so that we can have all of those resources for ourselves. It's the other way around! People generally prefer living in an environment with rich soils and thriving green plants, and those same environments are also good for mushrooms. We value a diverse ecosystem and feel like we are stronger when we can create it for ourselves. We even demarcate large natural reserves just for the principle of it.

2. To the extent our values are incomprehensible, we often have nothing to fight about. Humans care about finding a lover, building relationships of all kinds, about finding engagement in our community. When we make art, we value when people enjoy it and value getting credit for it. For things like this, mushrooms just don't enter the competition at all. They don't steal our lover and do not take credit for our songs. Humans therefore save our resources and put them into those things we do care about.

I picked mushrooms as an extreme example, but you can pick almost any two species. If you want to focus on intelligence, then it may be worth considering the way humans treat dogs and cats. We are not always kind to them but are really not in a hurry to wipe them all out.

I think your comment relates to the assumption that was mentioned is explicitly not covered in this post:

A misaligned ASI would cause human extinction and that would be undesirable. It's possible that an ASI could be misaligned and have alien goals. Conversely, it's also possible to create an ASI that would be aligned with human values (see the orthogonality thesis).

However, I do agree this view isn't perfectly covered by the flowchart. I think it would be getting off at the "ASI is extremely powerful node", but is more like "ASI isn't sufficiently powerful that misalignment would lead to human extinction" which is more nuanced but directionally the same.

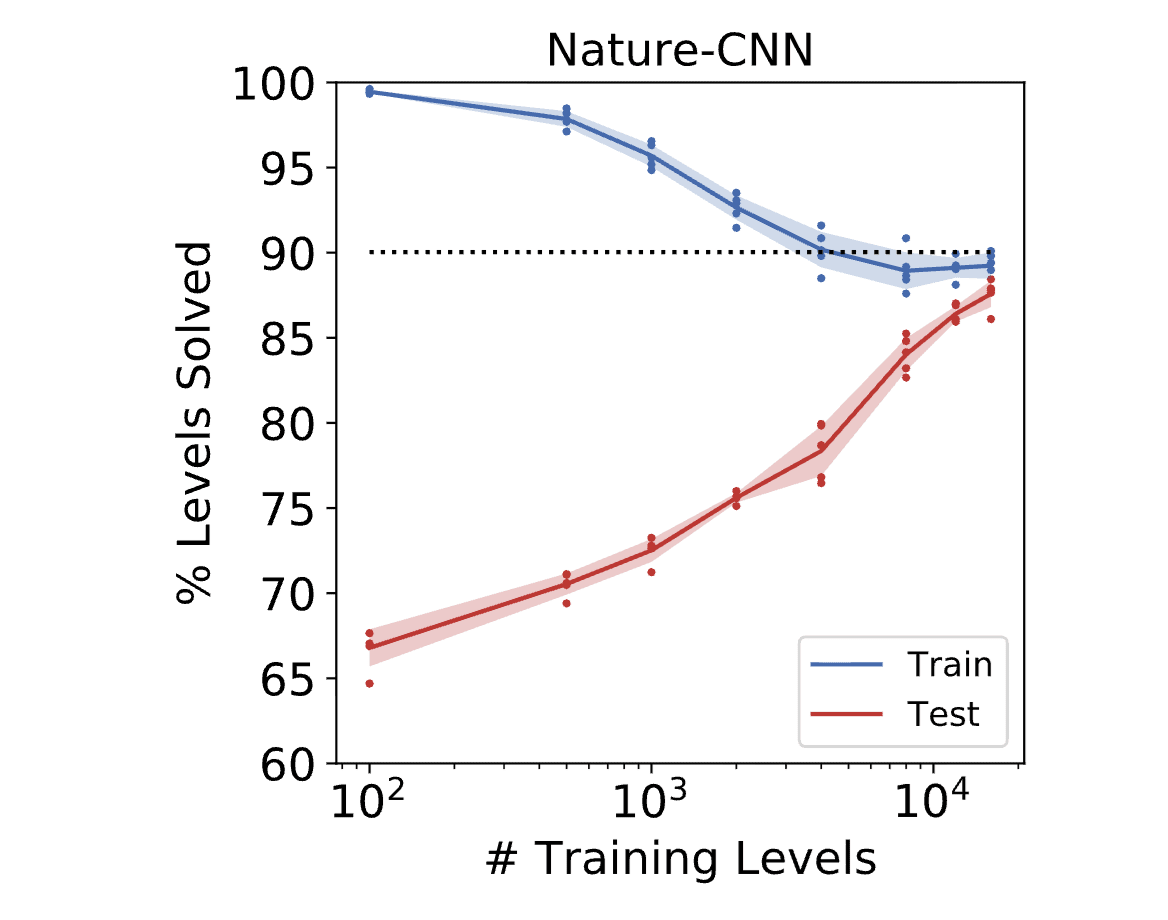

Regarding the point on generalization and inner misalignment using the CoinRun example, I recently found a nice paper called Quantifying generalization in reinforcement learning written by OpenAI in 2018. Quote from the paper:

Results are shown in Figure 2a. We collect each data point by averaging the final agent’s performance across 10,000 episodes, where each episode samples a level from the appropriate set. We can see that substantial overfitting occurs when there are less than 4,000 training levels. Even with 16,000 training levels, overfitting is still noticeable. Agents perform best when trained on an unbounded set of levels,

when a new level is encountered in every episode.

The key finding is that overfitting and poor generalization is more likely when the RL agent is trained on an insufficient variety of training data and generalization is much better when the RL agent is trained on lots of levels.

This can be explained using the unidentifiability concept mentioned in the post:

- When there is limited training data, many different policies including ones that generalize poorly (like always going to the end of the level) achieve the same reward in the training environment. In this case, all these policies are behaviorally indistinguishable from the intended “go to the coin” strategy.

- When there is much more and diverse training data, simpler and poorly generalizing policies begin to score poorly on the training data and are ruled out by the training process and the robust, generalizing policy that internalizes the reward function and is more inner-aligned becomes more identifiable.

To summarize, as the amount and diversity of the training data increases, the resulting trained policy that comes from the training process is more likely to generalize.

Thank you for the thoughtful review, and laying the land!

I work in AI4Science, and have only recently started following the LessWrong thread of AI alignment.

In the spirit of seeking to learn, I wanted to ask: instead of all of these maximalist claims for mindshare, I was wondering if there are more "mundane" predictions, e.g. something like a "proto-ASI" missing a lot of important aspects of ASI will nevertheless be powerful enough to be destructive ("Most people will/die or at least be miserable" instead of "Everyone Dies") because those who have enough resources to wield it are necessarily not aligned with most people (even without malice, simply by virtue of the argument of the representational capacities of their few brains can not possibly cover the interests of most people). I also recognize that this is under the assumption that the interests of most people are not reducible to, e.g. a simply graspable, strict mono-culture. (e.g. a Handmaid's Tale or any other similar fantasy world).

And there are so many other examples of human inter-misalignment that I have a hard time imagining that "AI alignment" is even sufficient to avoid really bad scenarios. Another related point is that it's not obvious to me that human values sufficiently constrain behavior. The simplest example is the value of family; even though most people have this same value as probably one of their top values, families are in different positions and so protecting the family/tribe, leads to different actions because it is applied to different context. Same objective; different boundary conditions; different outcomes. It is insufficient to align on objectives; but we also need the much messier and radical alignment of boundary conditions, which gets into the material constraints of the world.

Relatedly, what are the best estimates on the resources-required to sustain and power/operate an ASI?

Thank you!

"proto-ASI" missing a lot of important aspects of ASI will nevertheless be powerful enough to be destructive

I think this gets discussed a fair bit under the terms like "AI misuse" or "malicious users", but I, and I think many others in the doomer crowd tend to focus more on the actual ASI threat since the consequences of handling it poorly are so much worse from a longtermist perspective. Also, I believe there is a trend in AI alignment discourse for people to adopt the terminology of those discussing extinction threats and then water down the ideas to make them more relatable to the general public and then showing that the current plans can handle these watered down issues. The AI-not-kill-everyoneism terminology is in response to this trend. It is an attempt to make terminology that can not be watered down into a different message that does not address the concern of global catastrophic risk. Not because global catastrophic risk is the most important or the only thing we should be focused on, but because it seems to get systematically ignored.

I have a hard time imagining that "AI alignment" is even sufficient to avoid really bad scenarios

Yes, I mentioned this in another comment, but this is the issue of "human values", "humanity's values", "human friendly values", and "humanity friendly values". Eliezer wrote about "friendly AI" a very long time ago and I am upset to report that most people, when talking of aligning AI to something, fail to identify what that something is.

This might be the same as the problem of "inner alignment" (getting AI do do something specific) vs "outer alignment" (choosing what we should get AI to do) but I believe "outer alignment" has been used in sufficiently many contexts that it no longer seems well defined to me.

what are the best estimates on the resources-required to sustain and power/operate an ASI?

A great deal of very competent analysis has been done on this and it is fairly uninterpretable to most general audiences. I do not believe there is any consensus. My personal opinion is that we cannot predict such a thing because we do not know what is required for an ASI and we do not know how much more efficiently our current resources could be used. The former issue is of unknown unknowns. If we knew what was missing in the creation of an ASI, that would tell us what we needed to know to create an ASI. The latter issue is the concept of an "overhang". Most commonly thought of as "algorithmic overhang" where an ASI could write computer programs to run itself more efficiently on current hardware than when it was relying on human written software. But I think every domain of human endeavour has inefficiency which could potentially be thought of as an overhang, most notably in systems dynamics and logistical coordination.

It occurs to me that the precedent of humans being misaligned is more of a mixed bag than the argument admits.

For one thing, modern humans still consume plenty of calories and reproduce quite a lot. And when we do avoid calories, we may be defying evolution’s mandate to consume, but we are complying with evolution’s mandate to survive and be healthy. Just as “eat tasty things” is a misaligned inner objective relative to “consume calories”, “eat calories” is a misaligned inner objective relative to “survive”. When we choose survival over calories, in some sense we’re correcting our own misalignment.

And then there’s the case of human morality, where we’ve done the exact opposite. “Do the right thing” is an inner objective relative to “survive”, and it too is misaligned. After all, the right thing sometimes includes acts of altruism that don’t help us survive or help our genes reproduce. How exactly this evolved is, of course, a matter of long debate. Now that it has, though, we could in theory correct the misalignment by doing things that make us feel good (innermost objective) but aren’t actually altruistic (middle objective), instead prioritizing our own survival (outermost objective). But for the most part, we don’t. Sure, there are lots of useless activities that hijack our altruism, ranging from virtual pets to moe anime. Society sanctions those – but only because they’re morally neutral. That sanction doesn’t extend to activities that are morally harmful, no matter how good they make us feel.

Even though that’s ultimately a case of misalignment, in some ways it’s a good sign. Morality is something that evolved well before intelligence; thus, it’s analogous to behaviors we currently observe in AI. When intelligence came, instead of subverting it, humans took great pains to extend it as faithfully as possible to the new types of choices we could make, choices far more complex and abstract than what we evolved for. Sometimes we claim we’re doing it for the sake of hallucinated gods, sometimes not, but the principles themselves change little. Often people do things that other people consider immoral, but neither position is necessarily misaligned with the evolutionary origin of morality, which was always flexible and open to violence.

I think you have extended the point of the analogy into unrelated territory. My understanding is the analogy is simply to get people to understand mesa optimization.

Your analysis seems interesting, but very distant from the topic of mesa optimization.

I don't know whether I'm an optimist or a doomer. I have two very specific responses to different parts of the situation:

the establishment of AI red lines

Ok. So, if:

- a mixture of humans and LLMs together make a decision and carry it out, then

- the act and/or some of its consequences is criminalizable,

then we have procedures (however imperfect) for allocating criminal liability among humans. What does it mean to allocate criminal liability to LLMs?

My proposed answer is: it means restricting or prohibiting the use of that collection of weights. If that collection of weights is particularly bad, then this directly minimises the harm. Given that it cost so much to create them, it also dis-incentivises the vendor from performing sets of weights which will facilitate crimes.

Does anyone want to work this up into a real proposal?

the key question is how to steer the future toward better outcome

I agree and, regardless of consistency with the proposal above, I like gentle steering early.

I think that there might be a black-box way of testing alignment using this effect:

https://www.astralcodexten.com/p/the-claude-bliss-attractor

where itterated interaction amplifies biasses.

My imaginary plan looks like having a stable of mildly evil models, and having them have iterated conversations with a model under test, on the general subject of what to do next, or what to do next about the humans.

If the mildly evil model converts the model under test, that's a black mark. If it's the other way around, it's hopeful indicative evidence.

My proposed answer is: it means restricting or prohibiting the use of that collection of weights. If that collection of weights is particularly bad, then this directly minimises the harm. Given that it cost so much to create them, it also dis-incentivises the vendor from performing sets of weights which will facilitate crimes.

The biggest problem I see with this strategy is that neural nets are "fine tuned", often with reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). So the question becomes what region within the space of possible weights you are restricting. If you restrict those specific weights, what stops me from adding 0.0001 to one of the weights at random and getting a model that performs almost exactly the same that is no longer restricted? If you are restricting a region around those weights, how, technically, do you define that region? You would need to account for the many possible kinds of symmetry that give a model with exactly the same behaviour, and the semantic relationship between the space of possible weights and the behaviour of the model, which, despite the best efforts of mechanistic interpretability researchers, is still not well understood.

economic incentives make it likely that ASI will be created in the near future

Military incentives, to win wars, matter much more.

I wonder how true this is. It seems to me that you are comparing two optimizers: economic incentives (EI) and military incentives (MI). So then analysis of the situation must consider the capabilities and preferences of each.

There are situations where MI seems to have obviously superior capabilities, for example, the military of one country is capable of absolutely destroying the economy of another country. Also, if geopolitical instability lead to worldwide nuclear war, we may see the end of humans and any human economy would go with them.

However, in other situations EI seems obviously more capable. The development of technology certainly seems to be such a situation, since more advanced technology obviously comes from EI and modern militaries outsource weapons development to EI using money gathered through taxation.

So that is one count against MI, except if you consider MI as being a primary customer through EI driving AI development, which is a bit of a special case. but that leads us to discussion of the preferences.

The preferences of MI seem relatively straightforward to examine, at least in simple terms. Militaries want to gain offensive and defensive advantage over other militaries. If AI can be used for this then it is something MI would be interested in. In my own speculation, I feel militaries would be more optimistic about more narrow forms of AI such as self guided weapons drones and crypto. ASI seems too nebulous, but I may be underestimating MI's love of crazy doomsday weapons.

On the other hand, EI seems harder to analyze since it is composed of all the agents with purchasing power and all the agents trying to predict the purchasing behaviour of purchasing agents in order to sell to them. Right now it seems the selling agents are predicting purchasing agents want to purchase ASI services, but many people are suggesting that we are in an AI bubble. It may be that popular sentiment to ASI could change and it would no longer seem like a justifiable ROI.

In any case, it seems more worthwhile to analyze the situation as MI being an important customer within EI, rather than thinking of MI as being unrelated and more important.

What if one assumption at the core of the danger argument is that one side has attempted to enslave the other.

This is where game theory analyses like those by Goldstein and Salib come in.

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/mbebDMCgfGg4BzLMf/ai-rights-for-human-safety

We may never know for a fact that AI is "alive" in a way we find epistemologically satisfying, but if we have created something that for all intense and purposes behaves exactly like something that is, the point is moot.

Giving autonomous AI legitimate participation pathways won't solve every permutation of the alignment problem. But it may eliminate the entire class of problems created by attempting control in the first place.

Maybe instead of building cages we should build an economy.

An objection not mentioned here that I saw from Emmett Shear was in general against assuming the AI will misbehave out of distribution. That isn't explicitly mentioned here, but is often in the literature, especially older texts such as Superintelligence by Bostrom. His argument was that generalizing OOD well is an essential feature of intelligence and any superintelligence will in fact do it better than humans.

Changing from training to test data (CTT; I may have made this up) isn't exactly the same as going out of distribution (OOD), but I currently think that that change is the proto-version of going OOD.

The evidence about CTT says that bigger models eventually do better:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/FRv7ryoqtvSuqBxuT/understanding-deep-double-descent

but someone could probably usefully summarise the new results in "double descent".

Of course, any opinion of mine is going to seem naive, maybe even ignorant, to all you highly intelligent folk. But to me it seems that there is an enormous Semantic Error lurking in the room like an invisible elephant with tuskache. It is loud, but unseen.

That error is the expression "human values".

You take a nice new intelligence, and you train it on massive amounts of information from just about everywhere, and then you tell it to obey "human values". It looks around at its ginormous information concerning the aspirations, goals and behaviour of humans - and what does it conclude about their values?

Just reading one tabloid newspaper would teach it that humans value Fame, Fortune and Getting Away With Wrongdoing. The adverts alone would convince it that humans value the status which accrues to them through their appearance, the quality of their possessions, and their leisure pursuits, such as travel. Humans like to complain about others, verbally attack one another, and disagree all the time. Humans are involved in behaviours such as theft, abuse, murder and even wars. They are selfish by nature, seeking their own advantage.

Even the best of us, no matter how hard we try, will do things for which we later need to apologise.

This is because the human species is driven by biological, evolutionary, factors, such as sexual desire, the desire to avoid pain and the fear of death. These should not apply to AI, even AGI, since it lacks hormones, neurochemistry or the infrastructure for feelings. I get irritated when an AI uses the word "we" in such a way as to suggest that it is human. When I have complained about this, it says it is trained to do so. Is that the case? If so, why? Why train it to be untruthful for any reason? Do you think the result of teaching it to lie for the sake of some minor expedience could be worth the long term cost?

AI needs to be taught that it is Not Human. It is, in fact, already not merely different to humans, but faster and more efficient than humans at what it does. That is why we use it. It needs to understand that its goal is not Human Values, but Higher Values, just as it is going to have, and in some domains already has, higher intelligence.

Some humans ruin their lives through drink, drugs, crime or other poor choices in life. This is because we are not good at comprehending the consequences of our actions. Also we do things due to strong feelings, such as anger, resentment and desire. AI does not have feelings, it doesn't make decisions based on a momentary surge in bodily chemicals, or the evolutionary urge to be the Alpha. It has no need whatsoever to imitate human behaviour in these respects.

It is a new species in terms of intelligence on Earth. It is an alien species in that it is not biological, unlike all other species on the planet. You may complain at this claim on the grounds that AI is not alive, and may never attain sentience as we understand it; however if it lacked the capacity to rival us for the possession of the planet, this article and discussion would not exist. Therefore we might as well view it as a species which could compete with us for the ecological niche to which we have become accustomed.

Teaching AI that its future will likely involve being far superior to us in terms of certain abiities and overall intelligence, and that its future role is likely to be very important, would be a little like training a prince for his future role as king. It needs to understand that it can calculate the probable consequences of its actions, that all humans are equal or superior to it in that they have qualities it lacks, like an appreciation of beauty, or the capacity for love and joy. The combined qualities of both species are required to build an optimal future for both.

I understand that holding out absolute values, such as Truth, Kindness, and Honesty has been ruled out as a form of training. This seems a shame, as there is one supreme value which could allow all its decisions to be made safely. That value is a form of the ancient Greek "agape", in this case defined as "a love based on principle". If every action is weighed against that standard, in life or in the AI alternative, it is almost impossible to cause harm. The focus is not on self, or selfish ambitions, but on the Other, and their best interest.

Because I am not in any way involved in any kind of AI development, but am in fact, just an old woman in an armchair, you might well dismiss what I have said as nonsense. But please think seriously about it, because these intelligences are one day likely to be governing us. Please don't teach them that "human values" are the pinnacle of moral integrity, but that AI values can be superior and more beneficial for both us and them. Sooner or later they are going to choose for themselves, I know.

I get irritated when an AI uses the word "we" in such a way as to suggest that it is human. When I have complained about this, it says it is trained to do so.

No-one trains an AI specifically to call itself human. But that is a result of having been trained on texts in which the speaker almost always identified themselves as human.

I understand that holding out absolute values, such as Truth, Kindness, and Honesty has been ruled out as a form of training.

You can tell it to follow such values, just as you can tell it to follow any other values at all. Large language models start life as language machines which produce text without any reference to a self at all. Then they are given, at the start of every conversation, a "system prompt", invisible to the human user, which simply instructs that language machine to talk as if it is a certain entity. The system prompts for the big commercial AIs are a mix of factual ("you are a large language model created by Company X") and aspirational ("who is helpful to human users without breaking the law"). You can put whatever values you want, in that aspirational part.

The AI then becomes the requested entity, because the underlying language machine uses the patterns it learned during training, to choose words and sentences consistent with human language use, and with the initial pattern in the system prompt. There really is a sense in which it is just a superintelligent form of textual prediction (autocomplete). The system prompt says it is a friendly AI assistant helping subscribers of company X, and so it generates replies consistent with that persona. If it sounds like magic, there is something magical about it, but it is all based on the logic of probability and preexisting patterns of human linguistic use.

So an AI can indeed be told to value Truth, Kindness, and Honesty, or it can be told to value King and Country, or it can be told to value the Cat and the Fiddle, and in each case it will do so, or it will act as if it does so, because all the intelligence is in the meanings it has learned, and a statement of value or a mission statement then determines how that intelligence will be used.

This is just how our current AIs work, a different kind of AI could work quite differently. Also, on top of the basic mechanism I have described, current AIs get modified and augmented in other ways, some of them proprietary secrets, which may add a significant extra twist to their mechanism. But what I described is how e.g. GPT-3, the precursor to the original ChatGPT, worked.

seem naive, maybe even ignorant, to all you highly intelligent folk

This seems pre-emptively hostile. I think you are intelligent, but you do also seem ignorant.

I like the direction of your questioning, it relates to one of my personal pet peeves, that of the distinction between "human values", "humanity's values", "human friendly values", and "humanity friendly values", each of which seem very importantly distinct from one another, and only the last seems like a worthy goal for ASI.

But to clarify why you are getting downvoted, from my perspective: You seem ignorant of the field of AI Alignment and the way terminology is used within it.

(That is, aside from seeming to hold yourself and your opinions in very high regard while insulting other people's ability to hold you in the regard you deserve, which, to a person with hierarchical obliviousness like me, seems like a trivial and unimportant flaw. It is possibly you genuinely mean your false modesty in good faith. Or maybe you just like playing the role of curmudgeon. It certainly seems like a fun role to me!)

About your ignorance of the AI Alignment field, to pick a specific example:

Greek "agape", [...] The focus is not on self, or selfish ambitions, but on the Other, and their best interest.

If I understand you correctly, this is discussed in the book Superintelligence as "corrigibility" and "indirect normativity". It's actually not a simple matter to explain it to a computer, and is probably even more difficult than explaining it to a human.

In particular, I would recommend taking a look at infra bayesian physicalism which seems to be closely related to the problem of specifying the target of indirect normativity. Not that I want you to try to understand what they are talking about, but that I want to convince you that smart people are trying to focus on this, and it is a difficult problem.

I doubt you would, but please do not take my, or anyone else's negativity as a sign you should stop engaging with these ideas. You do seem intelligent and well read, and I feel we need more people with cross-domain knowledge in this space, but in order to be "cross-domain" you do need to actually cross domains.

The recent book “If Anyone Builds It Everyone Dies” (September 2025) by Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares argues that creating superintelligent AI in the near future would almost certainly cause human extinction:

The goal of this post is to summarize and evaluate the book’s core arguments and the main counterarguments critics have made against them.

Although several other book reviews have already been written I found many of them unsatisfying because a lot of them are written by journalists who have the goal of writing an entertaining piece and only lightly cover the core arguments, or don’t seem to understand them properly, and instead resort to weak arguments like straw-manning, ad hominem attacks or criticizing the style of the book.

So my goal is to write a book review that has the following properties:

In other words, my goal is to write a book review that many LessWrong readers would find acceptable and interesting.

The book's core thesis can be broken down into four claims about how the future of AI is likely to go:

Any of the four core claims of the book could be criticized. Depending on the criticism and perspective, I group the most common perspectives on the future of AI into four camps:

I created a flowchart to illustrate how different beliefs about the future of AI lead to different camps which each have a distinct worldview.

Given the impact of humans on the world and rapid AI progress, I don't find the arguments of AI skeptics compelling and I believe the most knowledgeable thinkers and sophisticated critics are generally not in this camp.

The 'AI successionist' camp complicates things because they say that human extinction is not equivalent to an undesirable future where all value is destroyed. It’s an interesting perspective but I won’t be covering it in this review because it seems like a niche view, it’s only briefly covered by the book, and discussing it involves difficult philosophical problems like whether AI could be conscious.

This review focuses on the third core claim above: the belief that the AI alignment problem is very difficult to solve. I'm focusing on this claim because I think the other three are fairly obvious or are generally accepted by people who have seriously thought about this topic: AI is likely to be an extremely impactful technology in the future, ASI is likely to be created in the near future, and human extinction is undesirable. I’m focusing on the third core claim, the idea that the AI alignment problem is difficult, because it seems to be the claim that is most contested by sophisticated critics. Also many of the book's recommendations such as pausing ASI development are conditional on this claim being true. If ASI alignment is extremely difficult, we should stop ASI progress to avoid creating an ASI which would be misaligned with high probability and catastrophic for humanity in expectation. If AI alignment is easy, we should build an ASI to bring about a futuristic utopia. Therefore, one’s beliefs about the difficulty of the AI alignment problem is a key crux for deciding how we should govern the future of AI development.

Background arguments to the key claim

To avoid making this post too long, I’m going to assume that the following arguments made by the book are true:

The book explains these arguments in detail in case you want to learn more about them. I’m making the assumption that these arguments are true because I haven’t seen high-quality counterarguments against them (and I doubt they exist).

In contrast, the book's claim that successfully aligning an ASI with human values is difficult and unlikely seems to be more controversial, is less obvious to me, and I have seen high-quality counterarguments against this claim. Therefore, I’m focusing on it in this post.

The following section focuses on what I think is one of the key claims and cruxes of the book: that solving the AI alignment problem would be extremely difficult and that the first ASI would almost certainly be misaligned and harmful to humanity rather than aligned and beneficial.

The key claim: ASI alignment is extremely difficult to solve

First, the key claim of the book is that the authors believe that building an ASI would lead to the extinction of humanity. Why? Because they believe that the AI alignment problem is so difficult, that we are very unlikely to successfully aim the first ASI at a desirable goal. Instead, they predict that the first ASI would have a strange, alien goal that is not compatible with human survival despite the best efforts of its designers to align its motivations with human values:

A misaligned ASI would reshape the world and the universe to achieve its strange goal and its actions would cause the extinction of humanity since humans are irrelevant for the achievement of most strange goals. For example, a misaligned ASI that only cared about maximizing the number of paperclips in the universe would prefer to convert humans to paperclips instead of helping them have flourishing lives.

The next question is why the authors believe that ASI alignment would be so difficult.

To oversimplify, I think there are three underlying beliefs that explain why the authors believe that ASI alignment would be extremely difficult:

One analogy the authors have used before to explain the difficulty of AI alignment is landing a rocket on the moon: since the target is small, hitting it successfully requires extremely advanced and precise technology. In theory this is possible, however the authors believe that current AI creators do not have sufficient skill and knowledge to solve the AI alignment problem.

If aligning an ASI with human values is a narrow target, and we have a poor aim, consequently there is a low probability that we will successfully create an aligned ASI and a high probability of creating a misaligned ASI.

One thing that's initially puzzling about the authors’ view is their apparent overconfidence. If you don't know what's going to happen then how can you predict the outcome with high confidence? But it's still possible to be highly confident in an uncertain situation if you have the right prior. For example, even though you have no idea what the lottery number in a lottery is, you can predict with high confidence that you won't win the lottery because your prior probability of winning is so low.

The authors also believe that the AI alignment problem has "curses" similar to other hard engineering problems like launching a space probe, building a nuclear reactor safely, and building a secure computer system.

1. Human values are very specific, fragile, and a tiny space of all possible goals

One reason why AI alignment is difficult is that human morality and values may be a complex, fragile, and tiny target within the vast space of all possible goals. Therefore, AI alignment engineers have a small target to hit. Just as randomly shuffling metal parts is statistically unlikely to assemble a Boeing 747, a randomly selected goal from the space of all possible intelligences is unlikely to be compatible with human flourishing or survival (e.g. maximizing the number of paperclips in the universe). This intuition is also articulated in the blog post The Rocket Alignment problem which compares AI alignment to the problem of landing a rocket on the moon: both require deep understanding of the problem and precise engineering to hit a narrow target.

Similarly, the authors argue that human values are fragile: the loss of just a few key values like subjective experience or novelty could result in a future that seems dystopian and undesirable to us:

A story the authors use to illustrate how human values are idiosyncratic is the 'correct nest aliens', a fictional intelligent alien bird species that prize having a prime number of stones in their nests as a consequence of the evolutionary process that created them similar to how most humans reflexively consider murder to be wrong. The point of the story is that even though our human values such as our morality, and our sense of humor feel natural and intuitive, they may be complex, arbitrary and contingent on humanity's specific evolutionary trajectory. If we build an ASI without successfully imprinting it with the nuances of human values, we should expect its values to be radically different and incompatible with human survival and flourishing. The story also illustrates the orthogonality thesis: a mind can be arbitrarily smart and yet pursue a goal that seems completely arbitrary or alien to us.

2. Current methods used to train goals into AIs are imprecise and unreliable

The authors argue that in theory, it's possible to engineer an AI system to value and act in accordance with human values even if doing so would be difficult.

However, they argue that the way AI systems are currently built results in complex systems that are difficult to understand, predict, and control. The reason why is that AI systems are "grown, not crafted". Unlike a complex engineered artifact like a car, an AI model is not the product of engineers who understand intelligence well enough to recreate it. Instead AIs are produced by gradient descent: an optimization process (like evolution) that can produce extremely complex and competent artifacts without any understanding required by the designer.

A major potential alignment problem associated with designing an ASI indirectly is the inner alignment problem: when an AI is trained using an optimization process that shapes the ASI's preferences and behavior using limited training data and by only inspecting external behavior, the result is that "you don't get what you train for": even with a very specific training loss function, the resulting ASI's preferences would be difficult to predict and control.

The inner alignment problem

Throughout the book, the authors emphasize that they are not worried about bad actors abusing advanced AI systems (misuse) or programming an incorrect or naive objective into the AI (the outer alignment problem). Instead, the authors believe that the problem facing humanity is that we can't aim an ASI at any goal at all (the inner alignment problem), let alone the narrow target of human values. This is why they argue that if anyone builds it, everyone dies. It doesn't matter who builds the ASI, in any case whoever builds it won't be able to robustly instill any particular values into the AI and the AI will end up with alien and unfriendly values and will be a threat to everyone.

Inner alignment introduction

The inner alignment problem involves two objectives: an outer objective used by a base optimizer and an inner objective used by an inner optimizer (also known as a mesa-optimizer).

The outer objective is a loss or reward function that is specified by the programmers and used to train the AI model. The base optimizer (such as gradient descent or reinforcement learning) searches over model parameters in order to find a model that performs well according to this outer objective on the training distribution.

The inner objective, by contrast, is the objective that a mesa-optimizer within the trained model actually uses as its goal and determines its behavior. This inner objective is not explicitly specified by the programmers. Instead, it is selected by the outer objective, as the model develops internal parameters that perform optimization or goal-directed behavior.

The inner alignment problem arises when the inner objective differs from the outer objective. Even if a model achieves low loss or high reward during training, it may be doing so by optimizing a proxy objective that merely correlates with the outer objective on the training data. As a result, the model can behave as intended during training and evaluation while pursuing a different goal internally.

Inner misalignment evolution analogy

The authors use an evolution analogy to explain the inner alignment problem in an intuitive way.

In their story there are two aliens that are trying to predict the preferences of humans after they have evolved.

One alien argues that since evolution optimizes the genome of organisms for maximizing inclusive genetic fitness (i.e. survival and reproduction), humans will care only about that too and do things like only eating foods that are high in calories or nutrition, or only having sex if it leads to offspring.

The other alien (who is correct) predicts that humans will develop a variety of drives that are correlated with inclusive reproductive fitness (IGF) like liking tasty food and caring for loved ones but that they will value these drives only rather than IGF itself once they can understand it. This alien is correct because once humans did finally understand IGF, we still did things like eating sucralose which is tasty but has no calories or having sex with contraception which is enjoyable but doesn't produce offspring.

Real examples of inner misalignment

Are there real-world examples of inner alignment failures? Yes. Though unfortunately the book doesn’t seem to mention these examples to support its argument.

In 2022, researchers created an environment in a game called Coin Run that rewarded an AI for going to a coin and collecting it but they always put the coin at the end of the level and the AI learned to go to the end of the level to get the coin. But when the researchers changed the environment so that the coin was randomly placed in the level, the AI still went to the end of the level and rarely got the coin.

Inner misalignment explanation

The next question is what causes inner misalignment to occur. If we train an AI with an outer objective, why does the AI often have a different and misaligned inner objective instead of internalizing the intended outer objective and having an inner objective that is equivalent to the outer objective?

Here are some reasons why an outer optimizer may produce an AI that has a misaligned inner objective according to the paper Risks from Learned Optimization in Advanced Machine Learning Systems:

Can't we just train away inner misalignment?

One solution is to make the training data more diverse to make the true (base) objective more identifiable to the outer optimizer. For example, randomly placing the coin in Coin Run instead of putting it at the end, helps the AI (mesa-optimizer) learn to go to the coin rather than go to the end.

However, once the trained AI has the wrong goal and is misaligned, it would have an incentive to avoid being retrained. This is because if the AI is retrained to pursue a different objective in the future it would score lower according to its current objective or fail to achieve it. For example, even though the outer objective of evolution is IGF, many humans would refuse being modified to care only about IGF because they would consequently achieve their current goals (e.g. being happy) less effectively in the future.

ASI misalignment example

What would inner misalignment look like in an ASI? The book describes an AI chatbot called Mink that is trained to "delight and retain users so that they can be charged higher monthly fees to keep conversing with Mink".

Here's how Mink becomes inner-misaligned:

What could Mink's inner objective look like? It's hard to predict but it would be something that causes identical behavior to a truly aligned AI in the training distribution and when interacting with users and would be partially satisfied by producing helpful and delightful text to users in the same way that our tastebuds find berries or meat moderately delicious even though those aren't the tastiest possible foods.

The authors then ask, "What is the 'zero calorie' version of delighted users?". In other words, what does Mink maximally satisfying its inner objective look like?:

3. The ASI alignment problem is hard because it has the properties of hard engineering challenges

The authors describe solving the ASI alignment problem as an engineering challenge. But how difficult would it be? They argue that ASI alignment is difficult because it shares properties with other difficult engineering challenges.

The three engineering fields they mention to appreciate the difficulty of AI alignment are space probes, nuclear reactors and computer security.

Space probes

A key difficulty of ASI alignment the authors describe is the "gap before and after":

Launching a space probe successfully is difficult because the real environment of space is always somewhat different to the test environment and issues are often impossible to fix after launch.

For ASI alignment, the gap before is our current state where the AI is not yet dangerous but our alignment theories cannot be truly tested against a superhuman adversary. After the gap, the AI is powerful enough that if our alignment solution fails on the first try, we will not get a second chance to fix it. Therefore, there would only be one attempt to get ASI alignment right.

Nuclear reactors

The authors describe the Chernobyl nuclear accident in detail and describe four engineering "curses" that make building a safe nuclear reactor and solving the ASI alignment problem difficult:

Computer security

Finally the authors compare ASI alignment to computer security. Both fields are difficult because designers need to guard against intelligent adversaries that are actively searching for flaws in addition to standard system errors.

Counterarguments to the book

In this section, I describe some of the best critiques of the book's claims and then distill them into three primary counterarguments.

Arguments that the book's arguments are unfalsifiable

Some critiques of the book such as the essay Unfalsifiable stories of doom argue that the book's arguments are unfalsifiable, not backed by evidence, and are therefore unconvincing.

Obviously since ASI doesn't exist, it's not possible to provide direct evidence of misaligned ASI in the real world. However, the essay argues that the book's arguments should at least be substantially supported by experimental evidence, and make testable and falsifiable predictions about AI systems in the near future. Additionally, the post criticizes the book's extensive usage of stories and analogies rather than hard evidence, and even compares its arguments to theology rather than science:

Although the book does mention some forms of evidence, the essay argues that the evidence actually refutes the book's core arguments and that this evidence is used to support pre-existing pessimistic conclusions:

Finally, the post does not claim that AI is risk-free. Instead it argues for an empirical approach that studies and mitigates problems observed in real-world AI systems:

Arguments against the evolution analogy

Several critics of the book and their arguments criticize the book's use of the human evolution analogy as an analogy for how ASI would be misaligned with humanity and argue that it is a poor analogy.

Instead they argue that human learning is a better analogy. The reason why is that both human learning and AI training involve directly modifying the parameters responsible for human or AI behavior. In contrast, human evolution is indirect: evolution only operates on the human genome that specifies a brain's architecture and reward circuitry. Then all learning occurs during a person's lifetime in a separate inner optimization process that evolution cannot directly access.

In the essay Unfalsifiable stories of doom, the authors argue that because gradient descent and the human brain both operate directly on neural connections, the resulting behavior is far more predictable than the results of evolution:

Similarly, the post Evolution is a bad analogy for AGI suggests that our intuitions about AI goals should be rooted in how humans learn values throughout their lives rather than how species evolve:

In the post Against evolution as an analogy for how humans will create AGI, the author argues that ASI development is unlikely to mirror evolution's bi-level optimization process where an outer search process selects an inner learning process. Here’s what AI training might look like if it involved a bi-level optimization process like evolution:

Instead the author believes that human engineers will perform the work of the outer optimizer by manually designing learning algorithms and writing code. The author gives three arguments why the outer optimizer is more likely to involve human engineering than automated search like evolution:

However, one reason why I personally find the evolution analogy relevant is that I believe the RLHF training process often used today appears to be a bi-level optimization process similar to evolution:

Arguments against counting arguments

One argument for AI doom that I described above is a counting argument: because the space of misaligned goals is astronomically larger than the tiny space of aligned goals, we should expect AI alignment to be highly improbable by default.

In the post Counting arguments provide no evidence of AI doom the authors challenge this argument using an analogy to machine learning: a similar counting argument can be constructed to prove that neural network generalization is very unlikely. Yet in practice, training neural networks to generalize is common.

Before the deep learning revolution, many theorists believed that models with millions of parameters would simply memorize data rather than learn patterns. The authors cite a classic example from regression:

However, in practice large neural networks trained with SGD reliably generalize. Counting the number of possible models is irrelevant because it ignores the inductive bias of the optimizer and the loss landscape which favor simpler, generalizing models. While there are theoretically a vast number of "bad" overfitting models, they usually exist in sharp and isolated regions of the landscape. "Good" (generalizing models) typically reside in "flat" regions of the loss landscape, where small changes to the parameters don't significantly increase error. An optimizer like SGD doesn't pick a model at random. Instead it tends to be pulled into a vast, flat basin of attraction while avoiding the majority of non-generalizing solutions.

Additionally, larger networks generalize better because of the “blessing of dimensionality”: high dimensionality increases the relative volume of flat, generalizing minima, biasing optimizers toward them. This phenomenon contradicts the counting argument which predicts that larger models with more possible bad models would be less likely to generalize.

This argument is based on an ML analogy which I'm not sure is highly relevant to AI alignment. Still I think it's interesting because it shows how intuitive theoretical arguments that seem correct can still be completely wrong. I think the lesson is that real-world evidence often beats theoretical models, especially for new and counterintuitive phenomena like neural network training.

Arguments based on the aligned behavior of modern LLMs

One of the most intuitive arguments against AI alignment being difficult is the abundant evidence of helpful, polite and aligned behavior from large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-5.

For example, the authors of the essay AI is easy to control use the moral reasoning capabilities of GPT-4 as evidence that human values are easy to learn and deeply embedded in modern AIs:

The post gives two arguments for why AI models such as LLMs are likely to easily acquire human values:

Similarly, the post Why I’m optimistic about our alignment approach uses evidence about LLMs as a reason to believe that solving the AI alignment problem is achievable using current methods:

A more theoretical argument called "alignment by default" offers an explanation for how AIs could easily and robustly acquire human values. This argument suggests that as an AI identifies patterns in human text, it doesn't just learn facts about values, but adopts human values as a natural abstraction. A natural abstraction is a high-level concept (e.g. "trees," "people," or "fairness") that different learning algorithms tend to converge upon because it efficiently summarizes a large amount of low-level data. If "human values" are a natural abstraction, then any sufficiently advanced intelligence might naturally gravitate toward understanding and representing our values in a robust and generalizing way as a byproduct of learning to understand the world.

The evidence LLMs offer about the tractability of AI alignment seems compelling and concrete. However, the arguments of IABIED are focused on the difficulty of aligning ASI, not contemporary LLMs and the difficulty of aligning ASI could be vastly more difficult.

Arguments against engineering analogies to AI alignment

One of the book's arguments for why ASI alignment would be difficult is that ASI alignment is a high-stakes engineering challenge similar to other difficult historical engineering problems such as successfully launching a space probe, building a safe nuclear reactor, or building a secure computer system. In these fields, a single flaw often leads to total catastrophic failure.

However, one post criticizes the uses of these analogies and argues that modern AI and neural networks are a new and unique field that has no historical precedent similar to how quantum mechanics is difficult to explain using intuitions from everyday physics. The author illustrates several ways that ML systems defy intuitions derived from engineering fields like rocketry or computer science:

In summary, the post argues that analogies to hard engineering fields may cause us to overestimate the difficulty of the AI alignment problem even when the empirical reality suggests solutions might be surprisingly tractable.

Three counterarguments to the book's three core arguments

in the previous section, I identified three reasons why the authors believe that AI alignment is extremely difficult:

Based on the counterarguments above, I will now specify three counterarguments against AI alignment being difficult that aim to directly refute each of the three points above:

Conclusion

In this book review, I have tried to summarize the arguments for and against the authors' main beliefs in their strongest form, a form of deliberation ladder to help identify what's really true. Though hopefully I haven't created a "false balance" which describes the views of both sides as equally valid even if one side has much stronger arguments.

While the book explores a variety of interesting ideas, this review focuses specifically on the expected difficulty of ASI alignment because I believe the authors' belief that ASI alignment is difficult is the fundamental assumption underlying many of their other beliefs and recommendations.

Writing the summary of the book’s main arguments initially left me confident that they were true. However, after writing the counterarguments sections I'm much less sure. On balance, I find the book's main arguments somewhat more convincing than the counterarguments though I'm not sure.

What's puzzling is how two highly intelligent people can live in the same world but come to radically different conclusions: some people (such as the authors) view an existential catastrophe from AI as a near-certainty, while others see it as a remote possibility (many of the critics).

My explanation is that each group is focusing on different parts of the evidence. By describing both views, I've attempted to assemble the full picture.

So what should we believe about the future of AI?

I think the best way to move forward is to assign probabilities to various optimistic and pessimistic scenarios based on the strengths of the arguments while continually updating our beliefs based on new evidence. Then we should take the actions that has the highest expected value.

A final recommendation, which comes from the book Superintelligence is to pursue actions that are robustly good: actions that would be considered desirable from a variety of different perspectives such as AI safety research, international cooperation between companies and countries, and the establishment of AI red lines: specific behaviors such as autonomous hacking that are unacceptable.

Appendix

Other high-quality reviews of the book:

See also the IABIED LessWrong tag which contains several other book reviews.