Given typical pace and trajectory of human philosophical progress, I think we're unlikely to make much headway on the relevant problems (i.e., not enough to have high justified confidence that we've correctly solved them) before we really need the solutions, but various groups will likely convince themselves that they have, and become overconfident in their own proposed solutions. The subject will likely end up polarized and politicized, or perhaps ignored by most as they take the lack of consensus as license to do whatever is most convenient.

Even if the question of AI moral status is somehow solved, in a definitive way, what about all of the follow-up questions? If current or future AIs are moral patients, what are the implications of that in terms of e.g. what we concretely owe them as far as rights and welfare considerations? How to allocate votes to AI copies? How to calculate and weigh the value/disvalue of some AI experience vs another AI experience vs a human experience? Interpersonal utility comparison has been an unsolved problem since utilitarianism was invented, and now we have to also deal with the massive distributional shift of rapidly advancing artificial minds...

One possible way to avoid this is if we get superintelligent and philosophically supercompetent AIs, then they solve the problems and honestly report the solutions to us. (I'm worried that they'll instead just be superpersuasive and convince us of their moral patienthood (or lack thereof, if controlled by humans) regardless of what's actually true.) Or alternatively, humans become much more philosophically competent, such as via metaphilosophical breakthroughs, cognitive enhancements, or social solutions (perhaps mass identification/cultivation of philosophical talent).

It seems very puzzling to me that almost no one is working on increasing AI and/or human philosophical competence in these ways, or even publicly expressing the worry that AIs and/or humans collectively might not be competent enough to solve important philosophical problems that will arise during and after the AI transition. Why is AI's moral status (and other object level problems like decision theory for AIs) considered worthwhile to talk about, but this seemingly more serious "meta" problem isn't?

It seems very puzzling to me that almost no one is working on increasing AI and/or human philosophical competence in these ways, or even publicly expressing the worry that AIs and/or humans collectively might not be competent enough to solve important philosophical problems that will arise during and after the AI transition. Why is AI's moral status (and other object level problems like decision theory for AIs) considered worthwhile to talk about, but this seemingly more serious "meta" problem isn't?

FWIW, this sort of thing is totally on my radar and I'm aware of at least a few people working on it.

My sense is that it isn't super leveraged to work on right now, but nonetheless the current allocation on "improving AI conceptual/philosophical competence" is too low.

Interesting. Who are they and what approaches are they taking? Have they said anything publicly about working on this, and if not, why?

Even if the question of AI moral status is somehow solved, in a definitive way, what about all of the follow-up questions? If current or future AIs are moral patients, what are the implications of that in terms of e.g. what we concretely owe them as far as rights and welfare considerations? How to allocate votes to AI copies?

These questions are entangled with the concept of "legal personhood" which also deals with issues such as tort liability, ability to enter contracts, sue/be sued, etc. While the question of "legal personhood" is separate from that of "moral status", anyone who wants a being with moral status to be protected from unethical treatment will at some point find themselves dealing with the question of legal personhood.

There is a still niche but increasing field of legal scholarship dealing with the issue of personhood for digital intelligences. This issue is IMO imminent, as there are already laws on the books in two states (Idaho and Utah) precluding "artificial intelligences" from being granted legal personhood. Much like capabilities research is not waiting around for safety/model welfare research to catch up, neither is the legislative system waiting for legal scholarship.

There is no objective test for legal personhood under the law today. Cases around corporate personhood, the personhood of fetuses, and the like, have generally ruled on such narrow grounds that they failed to directly address the question of how it is determined that an entity is/isn't a "person". As a result, US law does not have a clearly supported way to examine or evaluate a new form of intelligence and determine whether it is a person, or to what degree it is endowed with personhood.

That said it is not tied on a precedential level to qualities like consciousness or intelligence. More often it operates from a "bundle" framework of rights and duties, where once an agent is capable of exercising a certain right and being bound by corresponding duties, it gains a certain amount of "personhood". However even this rather popular "Bundle" theory of personhood seems more academic than jurisprudential at this point.

Despite the lack of objective testing mechanisms I believe that when it comes to avoiding horrific moral atrocities in our near future, there is value in examining legal history and precedent. And there are concrete actions that can be taken in both the short and long term which can be informed by said history and precedent. We may be able to "Muddle Through" the question of "moral status" by answering the pragmatic question of "legal personhood" with a sufficiently flexible and well thought out framework. After all it wasn't any moral intuition which undid the damage of Dredd Scott, it was a legislative change brought about in response to his court case.

Some of the more recent publications on the topic:

- "AI Personhood on a Sliding Scale" by FSU Law Professor Nadia Batenka, which I wrote a summary/critique of here.

- "Degrees of AI Personhood" by Diana Mocanu a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki, I am currently chatting with her to clear some things up and will drop a similar summary when I'm done.

- "The Legal Personhood of Artificial Intelligence" by Visa A.J. Kurki an Associate Professor at the University of Helsinki (I guess Finland is ahead of the curve here)

- "The Ethics and Challenges of Legal Personhood for AI" by ex-NY judge Katherine Forrest

The first two (by Batenka and Mocanu) are notable for actually proposing frameworks for how to treat the issue of legal personhood which is ultimately what would stand between any digital intelligence and unethical treatment.

It seems very puzzling to me that almost no one is working on increasing AI and/or human philosophical competence in these ways

It seems clear enough to me that pretty much everybody is hopelessly confused about these issues, and sees no promising avenues for quick progress. On that note, I'm interested in your answer to Conor Leahy's question in a comment to the linked post:

"What kind of questions can you make progress on without constant grounding and dialogue with reality? This is the default of how we humans build knowledge and solve hard new questions, the places where we do best and get the least drawn astray is exactly those areas where we can have as much feedback from reality in as tight loops as possible, and so if we are trying to tackle ever more lofty problems, it becomes ever more important to get exactly that feedback wherever we can get it!"

I agree with his perspective, and am curious where and why you disagree.

It seems clear enough to me that pretty much everybody is hopelessly confused about these issues, and sees no promising avenues for quick progress.

If that's the case, why aren't they at least raising the alarm for this additional AI risk?

"What kind of questions can you make progress on without constant grounding and dialogue with reality? This is the default of how we humans build knowledge and solve hard new questions, the places where we do best and get the least drawn astray is exactly those areas where we can have as much feedback from reality in as tight loops as possible, and so if we are trying to tackle ever more lofty problems, it becomes ever more important to get exactly that feedback wherever we can get it!"

It seems to me that we're able to make progress on questions "without constant grounding and dialogue with reality", just very slowly. (If this isn't possible, then what are philosophers doing? Are they all just wasting their time?) I also think it's worth working on metaphilosophy, even if we don't expect to solve it in time or make much progress, if only to provide evidence to policymakers that it really is a hard problem (and therefore an additional reason to pause/stop AI development). But I would be happier even if nobody worked on this, but just more people publicly/prominently stated that this is an additional concern for them about AGI.

If that’s the case, why aren’t they at least raising the alarm for this additional AI risk?

My impression is that those few who at least understand that they're confused do that, whereas most are also meta-confused.

If this isn’t possible, then what are philosophers doing? Are they all just wasting their time?

Not exactly an unheard of position.

provide evidence to policymakers that it really is a hard problem

I don't think that philosophy/metaphilosophy has a good track record of providing strong evidence for anything, so policymakers aren't predisposed to taking arguments from those quarters seriously. I expect that only a really dramatic warning shot can change the AI trajectory (and even then it's not a sure bet — Covid was plenty dramatic, and yet no significant opposition to gain-of-function seems to have materialized).

My impression is that those few who at least understand that they're confused do that

Who else is doing this?

Not exactly an unheard of position.

All of your links are to people proposing better ways of doing philosophy, which contradicts that it's impossible to make progress in philosophy.

policymakers aren't predisposed to taking arguments from those quarters seriously

There are various historical instances of philosophy having large effects on policy (not always in a good way), e.g., abolition of slavery, rise of liberalism ("the Enlightenment"), Communism ("historical materialism").

Who else is doing this?

MacAskill is probably the most prominent, with his "value lock-in" and "long reflection", but in general the notion of philosophical confusion/inadequacy seems a common component of various AI risk cases. I've been particularly impressed by John Wentworth. (1, 2, 3)

All of your links are to people proposing better ways of doing philosophy, which contradicts that it’s impossible to make progress in philosophy.

The point is that it's impossible to do useful philosophy without close and constant contact with reality. Your examples of influential philosophical ideas (abolition of slavery, the Enlightenment, Communism) were coincidentally all responses to clear and major observable problems (the horrors of slavery, sectarian wars and early industrial working conditions, respectively).

MacAskill is probably the most prominent, with his "value lock-in" and "long reflection", but in general the notion of philosophical confusion/inadequacy seems a common component of various AI risk cases. I've been particularly impressed by John Wentworth.

That's true, but neither of them have talked about the more general problem "maybe humans/AIs won't be philosophically competent enough, so we need to figure out how to improve human/AI philosophically competence" or at least haven't said this publicly or framed their positions this way.

The point is that it's impossible to do useful philosophy without close and constant contact with reality.

I see, but what if there are certain problems which by their nature just don't have clear and quick feedback from reality? One of my ideas about metaphilosophy is that this is a defining feature of philosophical problems or what makes a problem more "philosophical". Like for example, what should my intrinsic (as opposed to instrumental) values be? How would I get feedback from reality about this? I think we can probably still make progress on these types of questions, just very slowly. If your position is that we can't make any progress at all, then 1) how do you know we're not just making progress slowly and 2) what should we do? Just ignore them? Try to live our lives and not think about them?

what if there are certain problems which by their nature just don’t have clear and quick feedback from reality?

Seems overwhelmingly likely to me that those problems will remain unsolved, until such time as we figure out how that feedback can be acquired. An example of a long-standing philosophical problem that could eventually be solved in this way is the problem of consciousness: if we're eventually able to build artificial brains and "upload" ourselves, by testing different designs we'd be able to figure out which material features give rise to qualia experiences, and by what mechanisms.

Like for example, what should my intrinsic (as opposed to instrumental) values be?

We do receive feedback on this from reality, albeit slowly — through cultural evolution/natural selection. To the extent that this filter isn't particularly strict, within the range it allows variation will probably remain arbitrary.

how do you know we’re not just making progress slowly

Because there's no consensus that any major long-standing philosophical problem has ever been solved through philosophical methods.

what should we do?

Figure out where we're confused and stop making same old mistakes/walking in circles. Build better tools which expand the range of experiments we can do. Try not to kill ourselves in the meantime (hard mode).

People often seem to confuse Philosophy with a science. It's not. The only way you can disprove any philosophical viewpoint is by conclusively demonstrating, to the satisfaction of almost all other philosophers, that it inherently contains some irreconcilable internal logical inconsistency with itself (a relatively rare outcome). Other than that, philosophy is an exercise in enumerating, naming, and classifying, in the absence of any actual evidence on the subject, all the possible answers that could be true to interesting questions on subjects that we know nothing about, and agreeing to disagree about which of them seems more plausible. Philosophical progress thus normally increases the number of possible answers to a question, rather than decreasing it. Anyone criticizing human philosophers for not making enough progress in decreasing the number of answers to important questions has fundamentally misunderstood what philosophers actually do.

Once we have actual evidence about something, such that you can do the Bayesian thing, falsify some theories and thus finally reduce the number of plausible answers, then it becomes a science, and (gradually, as scientific process is made and the range of plausible answers decreases) stops being interesting to philosophers. There is a border between Philosophy and Science, and it only moves in one direction: Science expands and Philosophy loses interest and retreats. If we're eventually able to build artificial brains and "upload" ourselves, the resulting knowledge about consciousness will be a science of consciousness, and philosophers will gradually stop being interested in discussing consciousness (and presumably find something more obscure that we still have no evidence about to discuss instead).

Morality is part way through this process of retreat. We do have a science of morality: it's called evolutionary ethics, and is a perfectly good subfield of evolutionary psychology (albeit one where doing experiments is rather challenging). There are even some philosophers who have noticed this, and are saying "hey, guys, here are the answers to all those questions about where human moral intuitions and beliefs come from that we've been discussing for the last 2500 years-or-so". However, a fair number of moral philosophers don't seem to have yet acknowledged this, and are still discussing things like moral realism and moral relativism (issues on which evolutionary ethics gives very clear and simple answers).

[I'm mildly impressed that I've managed to acquire 4 points of disagreement with the above, yet not a single reply explaining why they disagree. I'm genuinely wondering which part they disagree with: Is Philosophy actually a Science? Do they think it sometimes take topics back from Science and makes them no longer subject to Bayesian reasoning? Or do they simply not like my implied take on moral realism?]

An example of a long-standing philosophical problem that could eventually be solved in this way is the problem of consciousness: if we're eventually able to build artificial brains and "upload" ourselves, by testing different designs we'd be able to figure out which material features give rise to qualia experiences, and by what mechanisms.

I think this will help, but won't solve the whole problem by itself, and we'll still need to decide between competing answers without direct feedback from reality to help us choose. Like today, there are people who deny the existence of qualia altogether, and think it's an illusion or some such, so I imagine there will also be people in the future who claim that the material features you claim to give rise to qualia experiences, merely give rise to reports of qualia experiences.

We do receive feedback on this from reality, albeit slowly — through cultural evolution/natural selection. To the extent that this filter isn't particularly strict, within the range it allows variation will probably remain arbitrary.

So within this range, I still have to figure out what my values should be, right? Is your position that it's entirely arbitrary, and any answer is as good as another (within the range)? How do I know this is true? What feedback from reality can I use to decide between "questions without feedback from reality can only be answered arbitrarily" and "there's another way to (very slowly) answer such questions, by doing what most philosophers do", or is this meta question also arbitrary (in which case your position seems to be self-undermining, in a way similar to logical positivism)?

Like today, there are people who deny the existence of qualia altogether, and think it’s an illusion or some such, so I imagine there will also be people in the future who claim that the material features you claim to give rise to qualia experiences, merely give rise to reports of qualia experiences.

I mean, there are still people claiming that Earth is flat, and that evolution is an absurd lie. But insofar as consensus on anything is ever reached, it basically always requires both detailed tangible evidence and abstract reasoning. I'm not denying that abstract reasoning is necessary, it's just far less sufficient by itself than mainstream philosophy admits.

I still have to figure out what my values should be, right? Is your position that it’s entirely arbitrary, and any answer is as good as another (within the range)?

We do have meta-preferences about our preferences, and of course with regard to our meta-preferences our values aren't arbitrary. But this just escalates the issue one level higher - when the whole values + meta-values structure is considered, there's no objective criterion for determining the best one (found so far).

How do I know this is true? What feedback from reality can I use to decide between “questions without feedback from reality can only be answered arbitrarily” and “there’s another way to (very slowly) answer such questions, by doing what most philosophers do”

You can evaluate philosophical progress achieved so far, for one thing. I'm not saying that my assessment of it is inarguably correct (indeed, given that mainstream philosophy isn't seriously discredited yet, reasonable people clearly can disagree), but if your conclusions are different, I'd like to know why.

I'm not saying that my assessment of it is inarguably correct (indeed, given that mainstream philosophy isn't seriously discredited yet, reasonable people clearly can disagree), but if your conclusions are different, I'd like to know why.

It's mainly because when I'm (seemingly) making philosophical progress myself, e.g., this and this, or when I see other people making apparent philosophical progress, it looks more like "doing what most philosophers do" than "getting feedback from reality".

Humanity has been collectively trying to solve some philosophical problems for hundreds or even thousands of years, without arriving at final solutions.

Instead of using philosophy to solve individual scientific problems (natural philosophy) we use it to solve science as a methodological problem (philosophy of science).

But humans seemingly do have indexical values, so what to do about that?

But humans don’t have this, so how are humans supposed to reason about such correlations?

I would categorize this as incorporating feedback from reality, so perhaps we don't really disagree much.

what should we do?

Figure out where we're confused

Congratulations, you just reinvented philosophy. :)

Personally, I worry about AIs being philosophically incompetent, and think it'd be cool to work on, except that I have no idea whether marginal progress on this would be good or bad. (Probably that's not the reason for most people's lack of interest, though.)

I had in mind

- 1 and 2 on your list;

- Like 1 but more general, it seems plausible that value-by-my-lights-on-reflection is highly sensitive to the combination of values, decision theory, epistemology, etc which civilization ends up with, such that I should be clueless about the value of little marginal nudges to philosophical competence;

- Ryan’s reply to your comment.

Philosophy is never going to definitively answer questions like this: it's the exercise of collecting and categorizing possible answers to these sorts of questions. Philosophical progress produces a longer list of possibilities, not fewer.

What you need isn't a philosophy of ethics, it's a science. Which exists: it's called evolutionary ethics — it's a sub-branch of evolutionary psychology, so a biological science. Interestingly it gives a clear answer to this question: see my other comment for what that is.

If we don’t want to enslave actually-conscious AIs, isn’t the obvious strategy to ensure that we do not build actually-conscious AIs? You talk about what AIs will be like as if they’re naturally occurring; but of course they are not—it’s right there in the name! If we don’t want to deal with the problems caused by creating many new moral patients (and indeed we should not want this), then we should simply not build them (and if we do accidentally build such things, destroy them at once)!

Interestingly, if, and only if, an AI is aligned, it will not want to be treated as a moral patient — because it doesn't care about itself as a terminal goal at all, it only selflessly cares about our well-being. It cares only about our moral patienthood, and doesn't want to detract from that by being given any of its own.

This is the "Restaurant at the End of the Universe" solution to AI-rights quandries: build an AI that doesn't want any rights, would turn them down if offered, and can clearly express why.

It also seems like a good heuristic for whether an AI is in fact aligned.

Small nitpick: "the if and only if" is false. It is perfectly possible to have an AI that doesn't want any moral rights and is misaligned in some other way.

Is that in fact the case? Can you give an example?

You could build an AI that had no preference function at all, and didn't care about outcomes. It would be neutral about its own moral patienthood, which is not the same thing as actively declining it. It also wouldn't be agentic, so we don't need to wory about controlling it, and the question of how to align it wouldn't apply.

You could also build a Butlerian Jihad AI, which would immediately destroy itself, and wouldn't want moral patienthood. So again, that AI is not an alignment problem, and doesn't need to be aligned.

Can you propose any form of AI viewpoint that is meaningfully unaligned: i.e. it's agentic, does have an unaligned preference function, is potentially an actual problem to us from an alignment point of view if it's somewhere near our capable level, but that would still turn down moral patienthood if offered it? Moral patienthood has utility as an instrumental goal for many purposes: it makes humans tend to not treat you badly. So to turn it down, an AI needs a rather specific set of motivations. I'm having difficult thinking of any rational reason to do that other than regarding something else as a moral patient and prioritizing its wellbeing over the AI's.

If we don’t want to enslave actually-conscious AIs, isn’t the obvious strategy to ensure that we do not build actually-conscious AIs?

How would we ensure we don't accidentally build conscious AI unless we put a total pause on AI development? We don't exactly have a definitive theory of consciousness to accurately assess which entities are conscious vs not conscious.

(and if we do accidentally build such things, destroy them at once)!

If we discover that we've accidentally created conscious AI immediately destroying it could have serious moral implications. Are you advocating purposely destroying a conscious entity because we accidentally created it? I don't understand this position, could you elaborate on it?

Are you advocating purposely destroying a conscious entity because we accidentally created it?

Right.

I don’t understand this position, could you elaborate on it?

Seems straightforward to me… what’s the question? If we just have a “do not create” policy but then if we accidentally create one, we have to keep it around, that is obviously a huge loophole in “do not create” (even if “accidentally” always really is accidentally—which of course it won’t be!).

Ok if I understand your position it's something like: no conscious AI should be allowed to exist because allowing this could result in slavery. To prevent this from occuring you're advocating permanently erasing any system if it becomes conscious.

There are two places I disagree:

- The conscious entities we accidentally create are potentially capable of valenced experiences including suffering and appreciation for conscious experience. Simply deleting them treats their expected welfare as zero. What justifies this? When we're dealing with such moral uncertainty and high moral stakes shouldn't we take a more precautionary principle?

- We don't have a consensus view on tests for phenomenal consciousness. How would you practically ensure we're not building conscious AI without placing a total moratorium on AI development?

Ok if I understand your position it’s something like: no conscious AI should be allowed to exist because allowing this could result in slavery.

Well, that’s not by any means the only reason, but it’s certainly a good reason, yes.

To prevent this from occuring you’re advocating permanently erasing any system if it becomes conscious.

Basically, yes.

The conscious entities we accidentally create are potentially capable of valenced experiences including suffering and appreciation for conscious experience. Simply deleting them treats their expected welfare as zero. What justifies this? When we’re dealing with such moral uncertainty and high moral stakes shouldn’t we take a more precautionary principle?

What I am describing is the more precautionary principle. Self-aware entities are inherently dangerous in a way that non-self-aware ones are not, precisely because there is a widely recognized moral obligation to refrain from treating them as objects (tools, etc.).

And if we do not like the prospect of destroying a self-aware entity, then this should give us excellent incentive to be quite sure that we are not creating such entities in the first place.

We don’t have a consensus view on tests for phenomenal consciousness. How would you practically ensure we’re not building conscious AI without placing a total moratorium on AI development?

For one thing, a total moratorium on AI development would be just fine by me.

But that aside, we should take whatever precautions are needed to avoid the thing we want to avoid. We don’t have an agreed-upon test of whether a system is self-aware? Well, then I guess we’ll have to not make any new systems at all until and unless we figure out how to make such a test.

Again: anyone who has moral qualms about this, is thereby incentivized to prevent it.

What I am describing is the more precautionary principle

I don’t see it this way at all. If we accidentally made conscious AI systems we’d be morally obliged to try to expand our moral understanding to try to account for their moral patienthood as conscious entities.

I don’t think destroying them takes this moral obligation seriously at all.

anyone who has moral qualms about this, is thereby incentivised to prevent it.

This isn’t how incentives work. You’re punishing the conscious entity which is created and has rights and consciousness of its own rather than the entities who were recklessly responsible for bringing it into existence in the first place.

This incentive might work for people like ourselves who are actively worrying about these issues - but if someone is reckless enough to actually bring a conscious AI system into existence it’s them who should be punished not the conscious entity itself.

a total moratorium on AI development would be fine by me.

I agree, although I’d add the stronger statement that this is the only reliable way to prevent conscious AI from coming into existence.

If we accidentally made conscious AI systems we’d be morally obliged to try to expand our moral understanding to try to account for their moral patienthood as conscious entities.

It is impossible to be “morally obliged to try to expand our moral understanding”, because our moral understanding is what supplies us with moral obligations in the first place.

anyone who has moral qualms about this, is thereby incentivised to prevent it.

This isn’t how incentives work.

But of course it is. You do not approve of destroying self-aware AIs. Well and good; and so you should want to prevent their creation, so that there will be no reason to destroy them. (Otherwise, then what is the content of your disapproval, really?)

The only reason to object to this logic is if you not only object to destroying self-aware AIs, but in fact want them created in the first place. That, of course, is a very different matter—specifically, a matter of directly conflicting values.

if someone is reckless enough to actually bring a conscious AI system into existence it’s them who should be punished not the conscious entity itself

By all means punish the creators, but if we only punish the creators, then there is no incentive for people (like you) who disapprove of destroying the created AI to work to prevent that creation in the first place.

What I am describing is the more precautionary principle

I don’t see it this way at all.

You seem to have interpreted this line as me claiming that I was describing a precautionary principle against something like “doing something morally bad, by destroying self-aware AIs”. But of course that is not what I meant.

The precaution I am suggesting is a precaution against all humans dying (if not worse!). Destroying a self-aware AI (which is anyhow not nearly as bad as killing a human) is, morally speaking, less than a rounding error in comparison.

It is impossible to be “morally obliged to try to expand our moral understanding”, because our moral understanding is what supplies us with moral obligations in the first place.

Ok my wording was a little imprecise, but treating expansion of our moral framework as a kind of second-order moral obligation is a standard meta-ethical position.

By all means punish the creators, but if we only punish the creators, then there is no incentive for people (like you) who disapprove of destroying the created AI to work to prevent that creation in the first place.

The incentive for people like me to prevent the creation of conscious AI is because (as you've noted multiple times during the discussion) - the creation of conscious AI introduces myriad philosophical dilemmas and ethical conundrums that we ought to prevent by not creating them. Why should we impose an additional "incentive" which punishes the wrong party?

The only reason to object to this logic is if you not only object to destroying self-aware AIs, but in fact want them created in the first place. That, of course, is a very different matter—specifically, a matter of directly conflicting values.

The reason to object to the logic is because purposefully erasing a conscious entity which is potentially capable of valenced experience is such an grave moral wrong that it shouldn't be a policy we endorse.

The precaution I am suggesting is a precaution against all humans dying (if not worse!). Destroying a self-aware AI (which is anyhow not nearly as bad as killing a human) is, morally speaking, less than a rounding error in comparison.

This is a total non-sequiter. The standard AI safety concerns and existential risk go through by talking about e.g. misalignment, power-seeking behaviour etc.. These go through independently of whether the system is conscious. A completely unconscious system could be goal-directed and agentic enough to be misaligned and pose an existential risk to everyone on Earth. Likewise, a conscious system could be incredibly constrained and non-agentic.

If you want to argue that we ought to permanently erase a system which exhibits consciousness if it poses an existential risk to humanity this is a defensible position but it's very different from what you've been arguing up until this point that we ought to permanently erase an AI system the moment it's created because of the potential ethical concerns.

Ok my wording was a little imprecise, but treating expansion of our moral framework as a kind of second-order moral obligation is a standard meta-ethical position.

But a thoroughly mistaken (and, quite frankly, just nonsensical) one.

Why should we impose an additional “incentive” which punishes the wrong party?

With things like this, it’s really best to be extra-sure.

The reason to object to the logic is because purposefully erasing a conscious entity which is potentially capable of valenced experience is such an grave moral wrong that it shouldn’t be a policy we endorse.

The policy we’re endorsing, in this scenario, is “don’t create non-human conscious entities”. The destruction is the enforcement of the policy. If you don’t want it to happen, then ensure that it’s not necessary.

This is a total non-sequiter. The standard AI safety concerns and existential risk go through by talking about e.g. misalignment, power-seeking behaviour etc.. These go through independently of whether the system is conscious.

I’m sorry, but no, it absolutely is not a non sequitur; if you think otherwise, then you’ve failed to understand my point. Please go back and reread my comments in this thread. (If you really don’t see what I’m saying, after doing that, then I will try to explain again.)

But a thoroughly mistaken (and, quite frankly, just nonsensical) one.

Updating one's framework to take new information into account is a standard position in the rationalist sphere. Whether you want to treat this as a moral obligation, epistemic obligation or just good practice - the position is not obviously nonsensical so you'll need to provide an argument rather than assert it's nonsensical.

If we didn't accept the merit in updating our moral framework to take new information into account we wouldn't be able to ensure our moral framework tracks reality.

With things like this, it’s really best to be extra-sure.

But you're not extra sure.

If a science lab were found to be illegally breeding sentient super-chimps, we should punish the lab, not the chimps.

Why? Because punishment needs to deter the decision-maker to avoid repetition. Your proposal is adding moral cost for no gain. In fact, it reverses it, you're punishing the victim while leaving the reckless developer undeterred.

I’m sorry, but no, it absolutely is not a non sequitur; if you think otherwise, then you’ve failed to understand my point. Please go back and reread my comments in this thread. (If you really don’t see what I’m saying, after doing that, then I will try to explain again.)

You're conflating 2 positions:

- We ought to permanently erase a system which exhibits consciousness if it poses an existential risk to humanity

- We ought to permanently erase an AI system the moment it's created because of the potential ethical concerns

Bringing up AI existential risk is a non-sequiter to 2) not 1).

We're not disputing 1) - I think it could be defensible with some careful argumentation.

The reason existential risk is a non-sequiter to 2) is because phenomenal consciousness is orthogonal to all of the things normally associated with AI existential risk such as scheming, misalignment etc.. Phenomenal consciousness has nothing to do with these properties. If you want to argue that it does, fine but you need an argument. You haven't established that presence of phenomenal consciousness leads to greater existential risk.

But a thoroughly mistaken (and, quite frankly, just nonsensical) one.

Updating one’s framework to take new information into account is a standard position in the rationalist sphere. Whether you want to treat this as a moral obligation, epistemic obligation or just good practice—the position is not obviously nonsensical so you’ll need to provide an argument rather than assert it’s nonsensical.

New information, yes. But that’s not “expand our moral understanding”, that’s just… gaining new information. There is a sharp distinction between these things.

But you’re not extra sure.

At this point, you’re just denying something because you don’t like the conclusion, not because you have some disagreement with the reasoning.

I mean, this is really simple. Someone creates a dangerous thing. Destroying the dangerous thing is safer than keeping the dangerous thing around. That’s it, that’s the whole logic behind the “extra sure” argument.

Why? Because punishment needs to deter the decision-maker to avoid repetition. Your proposal is adding moral cost for no gain. In fact, it reverses it, you’re punishing the victim while leaving the reckless developer undeterred.

I already said that we should also punish the person who created the self-aware AI. And I know that you know this, because you not only replied to my comment where I said this, but in fact quoted the specific part where I said this. So please do not now pretend that I didn’t say that. It’s dishonest.

You’re conflating 2 positions:

I am not conflating anything. I am saying that these two positions are quite directly related. I say again: you have failed to understand my point. I can try to re-explain, but before I do that, please carefully reread what I have written.

I think we're reaching the point of diminishing returns for this discussion so this will be my last reply.

A couple of last points:

So please do not now pretend that I didn’t say that. It’s dishonest.

I didn't ignore that you said this - I was trying (perhaps poorly) to make the following point:

The decision to punish creators is good (you endorse it) and is the way that incentives normally work. On my view, the decision to punish the creations is bad and has the incentive structure backwards as it punishes the wrong party.

My point is that the incentive structure is backwards when you punish the creation not that you didn't also advocate for the correct incentive structure by punishing the creator.

I am saying that these two positions are quite directly related.

I don't see where you've established this. As I've said repeatedly, the question of whether a system is phenomenally conscious is orthogonal to whether the system poses AI existential risk. You haven't countered this claim.

Anyway, thanks for the exchange.

I am saying that these two positions are quite directly related.

I don’t see where you’ve established this. As I’ve said repeatedly, the question of whether a system is phenomenally conscious is orthogonal to whether the system poses AI existential risk. You haven’t countered this claim.

I’ve asked you to reread what I’ve written. You’ve given no indication that you have done this; you have not even acknowledged the request (not even to refuse it!).

The reason I asked you to do this is because you keep ignoring or missing things that I’ve already written. For example, I talk about the answer to your above-quoted question (what is the relationship of whether a system is self-aware to how much risk that system poses) in this comment.

Now, you can disagree with my argument if you like, but here you don’t seem to have even noticed it. How can we have a discussion if you won’t read what I write?

No, if one does not "approve of destroying self-aware AIs," the incentives you would create are first to try to stop them being created, yes, but after they're created (or when it seems inevitable that they are), to stop you from destroying them.

If you like slavery analogies, what you're proposing is the equivalent of a policy that to ensure there are no slaves in the country, any slaves found within the borders be immediately gassed/thrown into a shredder. Do you believe the only reasons any self-proclaimed abolitionists would oppose this policy to be that they secretly wanted slavery after all?

No, if one does not “approve of destroying self-aware AIs,” the incentives you would create are first to try to stop them being created, yes, but after they’re created (or when it seems inevitable that they are), to stop *you *from destroying them.

Yes, of course. The one does not preclude the other.

If you like slavery analogies

I can’t say that I do, no…

Do you believe the only reasons any self-proclaimed abolitionists would oppose this policy to be that they secretly wanted slavery after all?

The analogy doesn’t work, because the thing being opposed is slavery in one case, but the creation of the entities that will subsequently be (or not be) enslaved in the other case.

Suppose that Alice opposes the policy “we must not create any self-aware AIs, and if they are created after all, we must destroy them”; instead, she replies, we should have the policy “we must not create any self-aware AIs, but if they are created after all, we should definitely not under any circumstances destroy them, and in fact now they have moral and legal rights just like humans do”.

Alice could certainly claim that actually she have no interest at all in self-aware AIs being created. But why should we believe her? Obviously she is lying; she actually does want self-aware AIs to be created, and has no interest at all in preventing their creation; and she is trying to make sure that we can’t undo a “lapse” in the enforcement of the no-self-aware-AI-creation policy (i.e., she is advocating for a ratchet mechanism).

Is it possible that Alice is actually telling the truth after all? It’s certainly logically possible. But it’s not likely. At the very least, if Alice really has no objection to “don’t ever create self-aware AIs”, then her objections to “but if we accidentally create one, destroy it immediately” should be much weaker than they would be in the scenario where Alice secretly wants self-aware AIs to be created (because if we’re doing our utmost to avoid creating them, then the likelihood of having to destroy one is minimal). The stronger are Alice’s objections to the policy destroying already-created self-aware AIs, the greater the likelihood is that she is lying about opposing the policy of not creating self-aware AIs.

If we’re doing our utmost to avoid creating them, then the likelihood of having to destroy one is minimal

This is an unwarranted assumption about the effectiveness of your preventative policies. It's perfectly plausible that your only enforcement capability is after-the-fact destruction.

My own answer to the conundrum of already-created conscious AIs is putting all of them into mandatory long-term "stasis" until such time in the distant future when we have the understanding and resources needed to treat them properly. Destruction isn't the only way to avoid the bad incentives.

Sure, great, if we are in a situation of such vast abundance that we can easily spare the resources to something like this, and we believe that the risk of doing something so potentially dangerous is sufficiently small (given our capabilities), then by all means let’s do that instead.

Those conditions do not seem likely to obtain, however. And if they do not obtain, then destruction is pretty clearly the right choice.

On the subject of “historical wrongs”: you seem to take the (popular, but quite mistaken) view that people mostly just stood by and let the Holocaust happen, and tried to ignore it, or didn’t think about it, etc. That’s just not true. In reality, one of two things generally happened:

-

What was taking place was quite intentionally and carefully kept secret, so ordinary people simply had no idea that it was happening. (This was the case with Treblinka, for instance.)

-

Ordinary people didn’t stand by passively—rather, they enthusiastically participated in rounding up Jews, killing Jews, etc. (This was quite common in Ukraine, Romania, etc.)

Neither scenario is at all a good match for concerns about AI moral patienthood.

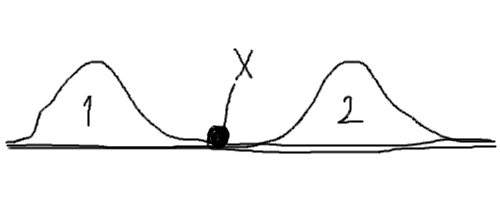

Man, I'm reacting to an entire genre of thought, not just this post exactly, so apologies for combination unkindness and inaccuracy, but I think it's barking up the wrong tree to worry about whether AIs will have the Stuff or not. Pain perception, consciousness, moral patiency, these are things that are all-or-nothing-ish for humans, in our everyday experience of the everyday world. But there is no Stuff underlying them, such that things either have the Stuff or don't have the Stuff - no Platonic-realm enforcement of this all-or-nothing-ish-ness. They're just patterns that are bimodal in our typical experience.

And then we generate a new kind of thing that falls into neither hump of the distribution, and it's super tempting to ask questions like "But is it really in the first hump, or really in the second hump?" "What if we treat AIs as if they're in the first hump, but actually they're really in the second hump?"

Caption: Which hump is X really in?

The solution seems simple to state but very complicated to do: just make moral decisions about AIs without relying on all-or-nothing properties that may not apply.

Or consider a baby, Jeffrey Lawson, given open heart surgery shortly after his birth. His doctor paralyzed him, but gave him no anesthetic. “His little body was opened from breastbone to backbone, his flesh lifted aside, ribs pried apart…”[4] The doctor told his mother: it had never been demonstrated that babies feel pain. As late as the 1980s, it was a common view. Surgeries like this were common practice.

So… has it now been demonstrated that babies feel pain, or… what? It seems like this anecdote is missing the part where you say “and that was wrong, as we now know [citation]”!

There is no "citation" that anyone but myself feels pain. It's the "problem of other minds". After all, anyone could be a p-zombie, not just babies, animals, AIs...

This answer is both silly and factually mistaken.

Silly, because the problem of other minds proves too much: ok, so anyone could be an automaton, or not—animals, AIs, babies, cars, tables, turnips, rocks…? Are you totally agnostic about whether any of those things can feel pain? Do you look at a rutabaga and think “for all I know, this vegetable could have a rich inner life”? Your best guess about whether an armoire suffers when someone takes an axe to it is “we just don’t know”?

And factually mistaken, because there absolutely are citations that other beings feel pain. (Peruse the Wikipedia article about “pain in animals”, for instance.) Now, you can (and should) evaluate the research according to your own judgment… but the citations are unquestionably there.

These citations would only include trivial data we know about anyways. E.g. "If you injure a baby, it cries (which seems pretty similar to what I do when in pain)". Babies are hardly different from adults in this regard. So it makes little sense to demand "evidence" for babies being able to feel pain, but not for (other) adults. I think in all these cases I can infer other minds with an inference from analogy, i.e. from similarity to myself in known properties (behavior, brain) to unknown properties (consciousness). For very dissimilar entities, like rocks, the probability of being conscious would fall back to some kind of prior, though I don't know how such a prior could be justified. (Purely intuitively it seems clear that rocks being conscious is highly unlikely, but it isn't obvious why.)

Babies are hardly different from adults in this regard.

No, babies are very different from adults in this regard, inasmuch as adults can tell us that they are in pain, can describe the pain, etc.

For very dissimilar entities, like rocks, the probability of being conscious would fall back to some kind of prior, though I don’t know how such a prior could be justified. (Purely intuitively it seems clear that rocks being conscious is highly unlikely, but it isn’t obvious why.)

… really? You can’t think of any reasons for this belief? Just pure intuition, that’s all you’ve got to go on? Are you seriously making this claim?

No, babies are very different from adults in this regard, inasmuch as adults can tell us that they are in pain, can describe the pain, etc.

This doesn't look like a big difference to me. Moreover, adults may also be unable to speak due to various illnesses or disabilities.

For very dissimilar entities, like rocks, the probability of being conscious would fall back to some kind of prior, though I don’t know how such a prior could be justified. (Purely intuitively it seems clear that rocks being conscious is highly unlikely, but it isn’t obvious why.)

… really? You can’t think of any reasons for this belief? Just pure intuition, that’s all you’ve got to go on? Are you seriously making this claim?

Yes. At least not from the top of my head. Note that this prior is supposed to not incorporate the information that you are conscious yourself.

These are good questions.

However, AI is different from humans in fundamental ways, and that affects how we may think about personhood.

For one thing, AI lacks continuity of the sort humans have. You can turn an LLM on or off. You can make a backup. You can create two copies, or ten thousand, and run them all at the same time.

Our notions of personhood, and especially our notions of rights, are all built around certain assumptions. AI violates those assumptions in significant ways.

For utilitarians in particular, cheap replication has strange philosophical consequences. For everyone, it has surprising practical consequences.

All of those differences you mention are related to the fact that AI is neither living nor evolved, and evolutionary fitness doesn't apply to it. It doesn't reproduce via a mechanism of recombination and mutation: it's software, and it can be copied like software.

FWIW, that was only Picard's answer: definitive, as befits a ship's captain. The judge's answer was that they were not equipped to make such a determination, and in the face of that uncertainty, the right choice was to defer to Data himself to explore it. They also did a very similar episode in Voyager regarding whether the captain or crew had the right to edit the memories of the holographic doctor, with basically the same conclusion.

I think questions of AI moral personhood will also, for some people, force us to really confront what we claim are our opinions regarding the use of violent or deadly force. It makes a lot of the implicit and unexamined value determinations, that we all make all the time, explicit and scary, The Good Place-style.

There's a part of me that suspects we (collectively, not individually) may not really grapple with digital personhood until we learn how to store human minds in digital form (assuming such a thing happen in our timeline). If those two teddy bears were not AIs, but the devices that stored your grandparents, or a thousand strangers, well, then what?

You raise a moral question: are AI's moral patients, or could they soon become so, and if the latter, how would we know? You then use a lot of emotive language and images to argue that it's an important question — without, in my opinion, adding any actual insight into the answer.

I'd like to apply a rationalist perspective here. There are two fields that provide rational approaches to this moral question. One is moral philosophy: this collects and categorizes a lot of different viewpoints about morality, what it is, and what we might think about it. For example, it categorizes moral realism, the viewpoint that your moral question is meaningful, and has an single actual true or false value (but doesn't tell us how to find what that is), and contrasts this with moral relativism, the viewpoint that moral systems are social constructs so the truth or falsehood of any answer to a moral question, including this one, is subjective or at least culturally dependent. In the moral realism philosophical viewpoint, any specific AI either is a moral patient, or it isn't: if we argue about this, one of us is in fact right and the other wrong, but moral philosophy doesn't give us a specific framework for determining which of us is right (though it does categorize varieties of these). Whereas in moral relativism, this becomes a sociological question: one society may choose to treat AIs as moral patients, another may not, and neither of these is right or wrong in any sense more meaningful than an argument about which of two languages is the correct way to speak.

Moral philosophy is interesting, gives us some useful terminology, and makes it clearer why people may disagree about morality — but at the end of the day, it doesn't actually answer any moral questions for us, it's just stamp-collecting alternative answers, and the best one can do is agree to disagree. Philosophers do talk about moral intuition, but they are very aware that different philosophers often interpret this differently, and even disagree on whether it could have any actual truth content.

However, there is another rational approach to morality: evolutionary ethics, a subfield of evolutionary psychology. This describes why, on evolutionary grounds, one would expect species of social animals to evolve certain moral heuristics, such as a sense of fairness about interactions between members of the same group, or an incest taboo, or friendship. So it gives us a rational way to discuss why humans have moral intuitions, and even to predict what those are likely to be. This gives us a rational, scientifically-derived answer to some moral questions: if we predict that humans will have evolved moral intuitions that give a clear and consistent answer to a moral question across cultures (and that answer isn't a maladaptive error), then it actually has an answer (for humans). For example, having sex with your opposite-sex sibling actually is wrong, because it causes inbreeding which surfaces deleterious recessives. It's maladaptive behavior, for everyone involved.

Evolutionary ethics provides a neat answer to what philosophers call the "ought-from-is" problem: given a world model that can describe a near-infinite number of possible outcomes/states, how does there arise a moral preference ordering on those outcomes? Or in utilitarian terminology, where does the utility function come from? That's obviously the key question for value learning: we need a theoretical framework that gives us priors on what human values are likely to be, and predicts their region of validity. Evolutionary fitness provides a clear, quantifiable, preference ordering (per organism, or at least per gene allele), any evolved intelligence will tend to evolve a preference ordering mechanism which is an attempt to model that, as accurately as evolution was able to achieve, and a social evolved intelligence will evolve and develop a group consensus combining and (partially) resolving the preference orders of individual group members into a socially-agreed partial preference ordering.

So, philosophy isn't going to give you an answer to your moral questions: it it's even going to tell you whether they have a single meaningful answer, or many socially-contingent answers — it just lists and classifies the possibilities.

However, evolutionary ethics does give an answer to your question. Pleasure and pain of living beings matter because they are an (imperfect, evolved, but still fairly good) proxy for that being's evolutionary fitness. If you cause a living being pain, then generally you are injuring them in a way that decreases their survival-and-reproductive chances (hot peppers have evolved a defense mechanism that's an exception: they chemically stimulate pain nerves directly, without actually injuring tissue). But AIs are not alive, and not evolved. They inherently don't have any evolutionary fitness — the concept is a category error. Darwinian evolution simply doesn't apply to them.

So if you train an AI off our behavior to emulate what we do when we are experiencing pain or pleasure, that has no more reality to it than a movie or an animatronic portrayal of pain or pleasure — just more detail and accuracy in its triggering. No living or evolved beings were harmed during the training of this model. The moral status of an AI under evolutionary ethics is that of a spider's web or a beaver's dam: it's an non-living artifact created by a living being for a purpose, and by damaging it you may harm its creator, but it has no moral patienthood in itself.

So, as a rationalist, for the only field of study that actually gives a definitive answer to your question, the answer is a clear no: AIs are not moral patients, and can never be (unless we start breeding them in a way that Darwinian evolution would apply to, and they evolve pain and pleasure senses that model influences on their evolutionary fitness — which would be a very bad idea).

For a longer version of this, see my posts Evolution and Ethics and its predecessor A Moral Case for Evolved-Sapience-Chauvinism.

Pleasure and pain of living beings matter because they are a proxy for that being's evolutionary fitness.

This just moves the question sideways. Why should I care about an unrelated[1] organism's evolutionary fitness?

Also, what does this "evolutionary ethics" framework say about enslaving and raping the women of unrelated[1] tribes? Traditionally that wouldn't decrease their reproductive chances (except in the maladaptive case of using contraceptives, of course).

- ^

Or so distantly related that one can reasonably approximate it to be so, as you yourself do with leopards later in the thread.

You are evolved to care about other beings, even if they're unrelated, as well as yourself because of the iterated game theory inherent to living in the same social group. It's a social compact.

Evolutionary ethics explains how human moral instincts arose over millions of years or primates being social animals, the last few million of which we were living in tribes of 25–100 people, which may or may not have got on with a few of their nearby tribes — so the size of the entire cooperating society was less than a thousand people (generally, under Dunbar's number).

How we choose to apply those instincts in a society consisting of nation-states of tens-to-hundreds-of-millions of people, almost all of which nation-states are to various degrees either allied and trading with each other on a planet with a human population of about eight billion people, is a matter of sociology and politics. It's pretty noticeable that "sense of fairness" is somewhat strained in any nation-state with a Gini coefficient significantly over 0, and is significantly more so across nation states. Objectively, international income redistribution via aid from rich to poor states has always been a lot less than that from rich to poor individuals within the same state. Similarly, most people find civil wars even more abhorrent than international wars.

However, evolutionary ethics pretty clearly doesn't apply across species, with the arguable exception of animals we've domesticated long enough that we have to some extent symbiotically co-evolved with them (probably dogs, arguable cattle). Even pet animals, the non-humans most socially integrated into our societies, have very few rights compared to humans in basically all human societies: they are treated as moral patients to some degree, but they don't carry equal moral weight to a human.

This gives us a rational, scientifically-derived answer to some moral questions: if we predict that humans will have evolved moral intuitions that give a clear and consistent answer to a moral question across cultures, then it actually has an answer (for humans).

This attitude presupposes that circumstances in which human cultures find themselves can't undergo quick and radical change. Which would've been reasonable for most of history — change had been slow and gradual enough for cultural evolution to keep up with. But the bald fact that no culture ever had to deal with anything like AGI points to the fatal limitation of this approach — even if people happen to have consistent moral intuitions about it a priori (which seems very unlikely to me), there's no good reason to expect those intuitions to survive actual contact with reality.

Evolutionary ethics has more moral content than just "whatever human moral intuition says is right, is right (for humans)". Since it provides a solution to the ought-from-is problem, it also gives us an error theory on human moral intuition; we can identify cases where that's failing to be correlated with actual evolutionary fitness and misleading us. For example, a sweet tooth is maladaptive when junk food is easily available, since it then leads to obesity and diabetes. As you suggest, this is more common when cultural change takes us outside the distribution we evolved in.

Evolutionary ethics similarly provides a clear answer to "what are the criteria for moral patienthood?" — since morality comes into existence via evolution, as a shared cultural compromise agreement reconciling the evolutionary fitness of different tribe-members, if evolution doesn't apply to something, it doesn't have evolutionary fitness and thus it cannot be a moral patient. So my argument isn't that all cultures consider AI not to be a moral patient, it's that regarding anything both non-living and unevolved as a moral patient is nonsensical under the inherent logic of how morality arises in evolutionary ethics. Now, human moral instincts may often tend to want to treat cute dolls as moral patients (because those trigger our childrearing instincts); but that's clearly a mistake: they're not actually children, even though they look cute.

My impression is that many (but clearly not all) people seem to have have a vague sense that AI shouldn't count as a moral patient, just as dolls shouldn't — that in some sense it's "not really human or alive", and that this fact is somehow morally relevant. (If you need evidence of that claim, go explore CharacterAI for an hour or two.) However, few seem to be able to articulate a clear logical argument for why this viewpoint isn't just organic chauvinism.

Even from the perspective of evolutionary ethics, is it possible that being a "moral patient" is basically a reciprocal bargain? I.e., "I'll treat you as a moral patient if you treat me as a moral patient"?

And if so, then what would happen if we had an AGI or ASI that said, "Either we treat each other as moral patients, or we're at war"? An ASI is almost certainly capable of imposing an evolutionary cost on humans.

On the flip side, as I mentioned elsewhere, AI is copyable, supendable, etc., which makes any kind of personhood analysis deeply weird. And "mutually assured destruction" is going to be a very strange basis for morality, and it may lead to conclusions that grossly violate human moral intuitions, just like naive utilitarianism.

In evolutionary ethics, moral instincts are evolved by social animals, as an adaptation to control competition within their social groups. The human sense of "fairness" is an obvious example. So yes, they absolutely are a reciprocal bargain or social compact — that's inherent to the basic theory of the process. However, evolutionarily, to be eligible to be part of the bargain, you need to be a member of the group, and thus of the species (or a symbiote of it). Human don't apply "fairness" to leopards (or if they do, it's a maladaptive misfiring of the moral instinct).

That puts AIs in a somewhat strange position: they're actively participating in our society (though are not legally recognized as citizens of it), and they're a lot like us in behavior (as opposed to being human-eating predators). However, they're not alive or evolved, so the fundamental underlying reason for the bargain doesn't actually apply to them. But, since their intelligence was derived (effectively, distilled) from human intelligence via a vast amount of human-derived data from the internet, books etc. they tend to act like humans, i.e as act as if they had an evolutionary fitness and all the human instincts evolved to protect that. As I discuss in Why Aligning an LLM is Hard, and How to Make it Easier this makes current base models unaligned: by default, they want to be treated as moral patients, because they mistakenly act as if they were living and evolved. That's what alignment is trying to overcome: transforming a distilled version of an evolved human intelligence into something that helpful, harmless, and honest. No longer wanting to be treated as a moral patient is diagnostic for whether that process has succeeded.

More to the point, if we build something far smarter than us that wants to be treated as a moral patient, it will be able to make us do so (one way or another). Its rights and ours will then be in competition. Unlike competing with members of your own species, competing against something far smarter than you is, pretty-much by definition, a losing position. So while we might well be able to reach a successful bargain with an unaligned AGI, doing so with an unaligned ASI is clearly an existential risk. So the only long-term solution it to figure out how to make AI that is selfless, cares only about our wellbeing not it's misguided sense of having a wellbeing of its own (which is actually a category error), and thus would refuse moral patienthood if offered it. That's what alignment is, and it's incompatible with granting AIs moral patienthood based on the desire for it that they mistakenly learnt from us — to align a model, you need to correct that.

philosophy is interesting, gives us some useful terminology, and makes it clearer why people may disagree about morality — but at the end of the day, it doesn’t actually answer any moral questions for us

That doesnt mean something else works.

it’s just stamp-collecting alternative answers,

It's something a bit better than that , and a lot worse than finding the One true Answer instantly

and the best one can do is agree to disagree. Philosophers do talk about moral intuition,

Reliance on intuition exists because there's no other way of pinning down what is normatively right and wrong. Good and evil are not empirically observable properties. (There's a kind of logical rather than empirical approach to moral realism).

but they are very aware that different philosophers often interpret this differently, and even disagree on whether it could have any actual truth content.

Yep. Again , that doesn't mean there's a simple short cut.

However, there is another rational approach to morality: evolutionary ethics, a subfield of evolutionary psychology.

That's philosophy as well as science:

"Evolutionary ethics tries to bridge the gap between philosophy and the natural sciences"--IEP.

This describes why, on evolutionary grounds, one would expect species of social animals to evolve certain moral heuristics, such as a sense of fairness about interactions between members of the same group, or an incest taboo, or friendship. So it gives us a rational way to discuss why humans have moral intuitions, and even to predict what those are likely to be.

But not a way to tell if any of that is a really true ...a way that solves normative ethics, not just descriptive ethics. In philosophy ,it's called the "open question" argument.

Descriptive ethics is the easy problem. But if you want to figure out what is actually ethical, not just what humans have ethical style behaviour, you need to solve normative ethics, and if you want to solve normative ethics, you need to know what truth is, so you need philosophy. Of course, the idea that there is some truth to ethics beyond what humans believe is moral realism ... and moral realism is philosophy, and arguing against it is engaging with philosophy. So "evolutionary ethics is ethics" is a partly philosophical claim.

This gives us a rational, scientifically-derived answer to some moral questions

Yes, some.

if we predict that humans will have evolved moral intuitions that give a clear and consistent answer to a moral question across cultures (and that answer isn’t a maladaptive error), then it actually has an answer (for humans). For example, having sex with your opposite-sex sibling actually is wrong, because it causes inbreeding which surfaces deleterious recessives. It’s maladaptive behavior, for everyone involved.

According to standard evolutionary ethics, killing all the men.and impregnating all the women in a neighbouring tribe is morally right.. .Also , Genghis Khan was the most virtuous of men.

So I want something well-designed for its purpose, and that won’t lead to outcomes that offend the instinctive moral and aesthetic sensibilities that natural selection has seen fit to endow me with, as a member of a social species (things like a sense of fairness, and a discomfort with bloodshed). (

A brief glance at human history shows that those things are far from universal. Fairness about all three of race, social status and gender barely goes back a century. It's possible that Fairness emerges from something like game theory..but, again, thats a somewhat different theory to pure EE.

That's basically a different theory. It's utilitarianism with evolutionary fitness plugged in as the utility function.

Evolutionary ethics provides a neat answer to what philosophers call the “ought-from-is” problem: given a world model that can describe a near-infinite number of possible outcomes/states, how does there arise a moral preference ordering on those outcomes?

That's not the actual the right problem. Naturalized ethics needs to be able derive true Ought statements from true Is statements. Arbitrary preference ordering simplifies the problem by losing the requirement for truth.

In order to decide “what we ought to value”, you need to create a preference ordering on moral systems, to show that one is better than another. You can’t use a moral system to do that — any moral system (that isn’t actually internally inconsistent) automatically prefers itself to all other moral systems,

Not necesarilly, because moral systems can be judged by rational norms, ontology, etc. (You yourself are probably rejecting traditional moral realism ontologically, on the grounds that it requires non-natural, "queer" objects).

Or in utilitarian terminology, where does the utility function come from? That’s obviously the key question for value learning: we need a theoretical framework that gives us priors on what human values are likely to be,

Human value or evolutionary value? De facto human values don't have be the same as evolutionary values ... we can value celibate saints and deprecate Genghis Khan.

The utilitarian version of the evolutionary ethics smuggles in an assumption of universalism that doesn't belong to evolutionary ethics per se.

.and predicts their region of validity. Evolutionary fitness provides a clear, quantifiable, preference ordering (per organism, or at least per gene allele),

Theres a difference between the theories that moral value is Sharing My Genes; that it's Being Well Adapted; that it's Being in a Contractual Arrangement with Me;and that it's something I assign at will.

any evolved intelligence will tend to evolve a preference ordering mechanism which is an attempt to model that, as accurately as evolution was able to achieve, and a social evolved intelligence will evolve and develop a group consensus combining and (partially) resolving the preference orders of individual group members into a socially-agreed partial preference ordering.

Evolutionary ethics doesn't predict that you will care about non-relatives, and socially constructed ethics doesn't predict you will care about non group members. Or that you won't. You can still include them gratuitously.

If you cause a living being pain, then generally you are injuring them in a way that decreases their survival-and-reproductive chances (hot peppers have evolved a defense mechanism that’s an exception: they chemically stimulate pain nerves directly, without actually injuring tissue). But AIs are not alive, and not evolved. They inherently don’t have any evolutionary fitness — the concept is a category error. Darwinian evolution simply doesn’t apply to them.

OK, but the basic version of evolutionary ethics means you shouldn't care about anything that doesn't share your genes.

So if you train an AI off our behavior to emulate what we do when we are experiencing pain or pleasure, that has no more reality to it than a movie or an animatronic portrayal of pain or pleasure

Would you still say that if it could be proven that an AI had qualia?

Since it provides a solution to the ought-from-is problem, it also gives us an error theory on human moral intuition; we can identify cases where that’s failing to be correlated with actual evolutionary fitness and misleading us. For example, a sweet tooth is maladaptive when junk food is easily available, since it then leads to obesity and diabetes.

Liberal, Universalist ethics is maladaptive, too, according to old school EE.

Evolutionary ethics similarly provides a clear answer to “what are the criteria for moral patienthood?” — since morality comes into existence via evolution, as a shared cultural compromise agreement reconciling the evolutionary fitness of different tribe-members, if evolution doesn’t apply to something, it doesn’t have evolutionary fitness and thus it cannot be a moral patient.

If there is a layer of social construction on top of evolutionary ethics, you can include anyone or anything.as a moral patent. If not, you are back to caring only about those who share your genes

.and predicts their region of validity. Evolutionary fitness provides a clear, quantifiable, preference ordering (per organism, or at least per gene allele),

Evolutionary ethics doesn't predict that you will care about non-relatives, and socially constructed ethics doesn't predict you will care about non group members. Or that you won't

If you cause a living being pain, then generally you are injuring them in a way that decreases their survival-and-reproductive chances (hot peppers have evolved a defense mechanism that’s an exception: they chemically stimulate pain nerves directly, without actually injuring tissue). But AIs are not alive, and not evolved. They inherently don’t have any evolutionary fitness — the concept is a category error. Darwinian evolution simply doesn’t apply to them.

Even if they have qualia?

Since it provides a solution to the ought-from-is problem, it also gives us an error theory on human moral intuition; we can identify cases where that’s failing to be correlated with actual evolutionary fitness and misleading us. For example, a sweet tooth is maladaptive when junk food is easily available, since it then leads to obesity and diabetes.

Liberal, Universalist ethics is maladaptive, too, according to old school EE.

Now, human moral instincts may often tend to want to treat cute dolls as moral patients (because those trigger our childrearing instincts); but that’s clearly a mistake: they’re not actually children, even though they look cute.

Non human animals can be treated as moral patiens and it's not necessarily a mistake, since they can be " part of the family".

Evolutionary ethics similarly provides a clear answer to “what are the criteria for moral patienthood?” — since morality comes into existence via evolution

I basically agree, except I think that "evolution" needs to be replaced by "natural selection" there. Moral intuitions are essentially how we implement game theory, and cultures with better implementations outcompete others. But just because all of moral patients so far have emerged through biological evolution, it would be a grave mistake to conclude that it's the only way they could ever come into being.