I think this is missing important reasons why current AIs don't do more instrumental power-seeking. Some other reasons from a post I wrote recently (the post is about intermediate steps of reasoning because it was about scheming reasoning, but it applies roughly as well to intermediate power-seeking actions - the main difference being that intermediate power-seeking actions may be directly selected for or against depending on misc details of what RL looks like):

- The human-like pretraining prior is mostly benign and applies to some intermediate steps of reasoning: it puts a very low probability on helpful-but-scheming agents doing things like trying very hard to solve math and programming problems;

- Short speed-prior-constrained reasoning and long reasoning are correlated: the weights that generate the final tokens, that generate the CoT when producing short CoTs, and the ones generating the CoT when producing long CoTs are the same, and while it would be possible to train the model to have different “personalities” in these three situations, the prior puts a high weight on these three personalities being similarly benign.

- Reward hacking would need to be cursed to strongly push against the mostly benign short-reasoning human priors: it does not just need to encourage unintended behaviors; it needs to encourage the kind of unintended behaviors that strongly favors schemers - and I argue current reward hacks mostly aren’t;

The first bullet point here is what I see as the most important factor for why current AI doesn't seek extreme power: they are best thought of not as being intrinsically motivated to complete tasks, but rather as having a reflex to complete contexts in a human-like way.

Maybe RL focusses this reflex and adds some degree of motivation to models, but I doubt this effect is large. My reasoning for this is that the default behavior of a pretrained model is to act like it is pursuing a goal when the inputted context suggests this, so there is little reward/gradient pressure to instill additional goal-pursuing drive.

I stand by my basic point in Varieties Of Doom that these models don't plan very much yet, and as soon as we start having them do planning and acting over longer time horizons we'll see natural instrumental behavior emerge. We could also see this emerge from e.g. continuous learning that lets them hold a plan in implicit context over much longer action trajectories.

"Secondarily, current models don’t operate for long enough (or on hard enough problems) for these convergent instrumental incentives to be very strong."

I'm worried that when it comes to Claude Code, this is not a base capabilities problem, but an elicitation one. It feels very plausible to me that with the correct harness, you could actually get an assemblage that is capable of arbitrary long horizon work.

Like - do humans actually have a long time horizon? The Basic Rest-Activity Cycle suggests we work in ~90 minute bursts at most. If true, then the base models are already there. All we would need is a way to mimic or substitute the cognitive scaffolding that we use to pull off our own arbitrary time horizons.

I'm envisioning an "assembly line" of cognitive labor - if Claude Code has 30-90 minute time horizons on every task natively, then you figure out a way to have it orchestrate the chopping up of arbitrary tasks into bits that dedicated subagents can do. Then you add a suite of epistemic tools, permanent memory, version control, reflexes; self-improvement via self-reflection, objective tests, and external research; the ability to build out its own harness; and so on: all the individual ingredients needed to get a bootstrapping functional cognitive laborer. [Edit: I'm very concerned this is an infohazard!!!]

Do we know that this can't work right now? Has anyone really tried? I've been looking and I don't see anyone doing this to the maximal extent I'm envisioning, but it seems inevitable that either someone will, either in the hacker community or at the frontier labs. I'm working on putting something like this together but, thinking about it, I'm really worried I shouldn't.

The Basic Rest-Activity Cycle suggests we work in ~90 minute bursts at most.

Surely when I come back to work after a 20 minute break I can regain much more context much more effectively than if Claude runs out of context window, and the context is compacted for the next Claude instance.

In conversations about this that I've seen the crux is usually:

Do you expect greater capabilities increases per dollar from [continued scaling by ~the current* techniques] or by some [scaffolding/orchestration scheme/etc].

The latter just isn't very dollar efficient, so I think we'd have to see the existing [ways to spend money to get better performance] get more expensive / hit a serious wall before sufficient resources are put into this kind of approach. It may be cheap to try, but verifying performance on relevant tasks and iterating on the design gets really expensive really quickly. On the scale-to-schlep spectrum, this is closer to schlep. I think you're right that something like this could be important at some point in the future, conditional on much less efficient returns from other methods.

This is a bit of a side note, but I think your human analogy for time horizons doesn't quite work, as Eli said. The question is 'how much coherent and purposeful person-minute-equivalent-doing can an LLM execute before it fails n percent of the time?' Many person-years of human labor can be coherently oriented toward a single outcome (whether it's one or many people involved). That the humans get sleepy or distracted in-between is an efficiency concern, not a coherence concern; it affects the rate at which the work gets done, but doesn't put an upper bound on the total amount of purposeful labor that can hypothetically be directed, since humans just pick up where they left off pursuing the same goals for years and years at a time, while LLMs seem to lose the plot once they've started to nod off.

While the particulars of your argument seem to me to have some holes, I actually very much agree with your observation we don't know what the upper limit of properly orchestrated Claude instances are, and that targeted engineering of Claude-compatible cognitive tools could vastly increase its capabilities.

One idea I've been playing with for a really long time is that the Claudes aren't the actual agents, but instead just small nodes or subprocesses in a higher-functioning mind. If I loosely imagine a hierarchy of Claudes, each corresponding roughly to system-1 or subconscious deliberative processes, with the ability to write and read to files as a form of "long term memory/processing space" for the whole system, and I imagine that by some magical oracle process they coordinate/delegate as well as Claudes possibly can, subject to a vague notion of "how smart Claude itself is", I see no reason a system like this can't already be an AGI, and cannot in principle be engineered into existence using contemporary LLMs.

(However, I will say that this thing sounds pretty hard to actually engineer, i.e, it being "just an engineering problem" doesn't mean it would happen soon, but OTOH maybe it could if people would try the right approach hard enough. I can't imagine a clean way of applying optimization pressure to the Claudes in any such setup that isn't an extremely expensive and reward-sparse form of RL.)

By my state of knowledge, it is an open question whether or not we will create AIs that are broadly loyal like this. It might not be that hard, if we’re trying even a little.

Curious about the story you'd tell of this happening? It looks to me quite implausible that we'd pull this off with anything like current techniques.

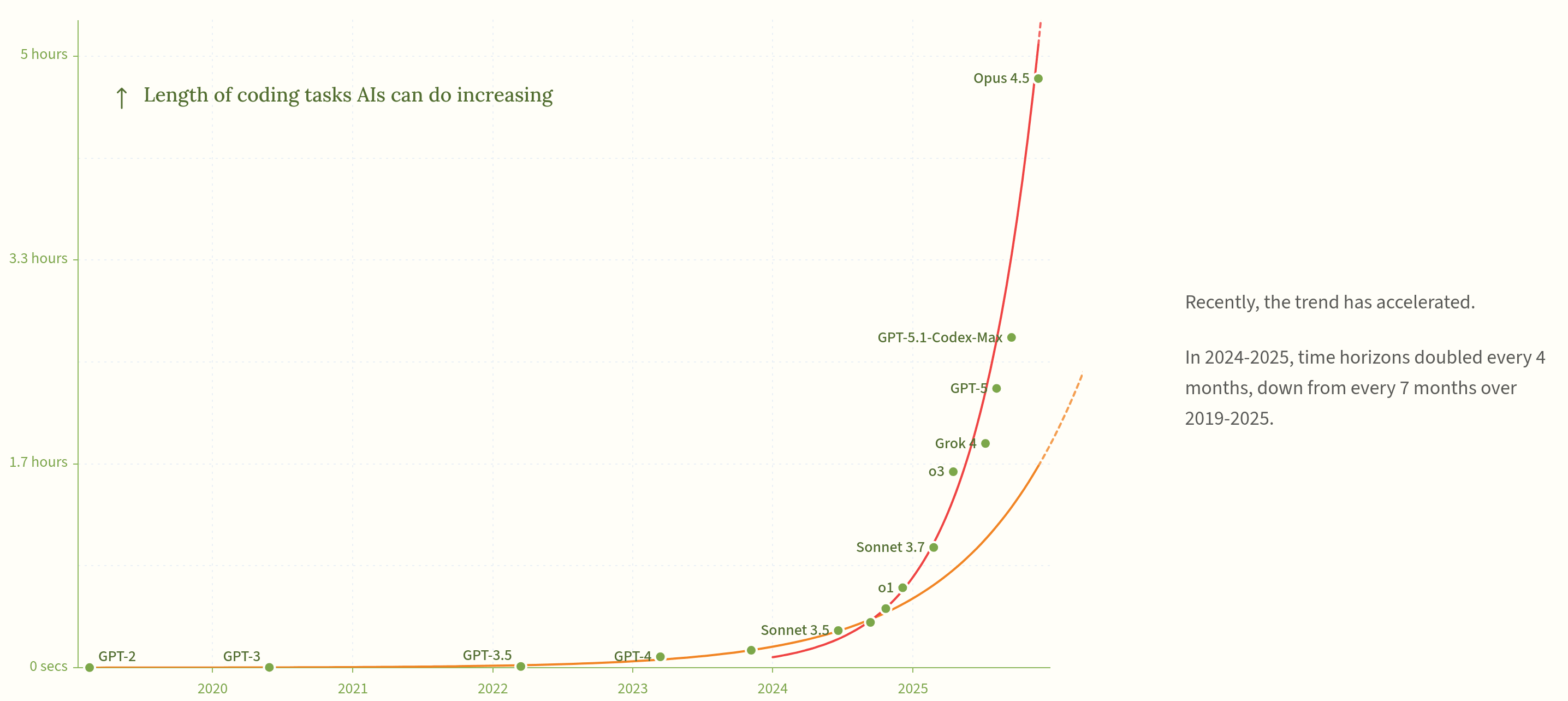

The task time horizon of the AI models doubles about every 7 months.

We're pretty clearly in the 4 month doubling world at this point:

I use the top 4-5 models for fun and profit several hours a day, and my distinct impressions is that they do not CARE. They LARP as a human, but they have no drive and no values. These might emerge at some point, but I have not seen any progress in the last year or so. Then again, progress is discontinuous and hard to anticipate. We are lucky that is the case. In the famous Yud-Karn debate from over a decade ago so far Holden is right: we get smart tools, not true agents, despite all the buzzwords. They don't care about what is true, or accurate, they hallucinate the moment you are not looking, or don't close the feedback loop yourself. They could. But they do not. Seems like a small price to pay for non-extinction though.

If I try to imagine a world in which AIs somehow look like this around AGI (like, around when the "tasks" these AIs could do start including solving millennium prize problems), I strongly feel like I should then imagine something like humans prompting an AI (or a society of AIs) with like "ok now please continue on your path to becoming a god and make things super-duper-good (in the human sense) forever" (this could be phrased more like "please run our companies/states/etc. while being really good" or "please make an initial friendly ASI sovereign" or "please solve alignment" or whatever), with everything significant being done by AIs forever after. And I think it's very unlikely this leads to a future remotely as good as it could be — it'll lead to something profoundly inhuman instead.

Similarly, Claude plausibly does have a convergent incentive to hack out of its machine and escape onto the internet, but it can’t realistically do that yet, even if it wanted to.

A sentence or so of explanation of how we know "it can't realistically do that yet" (or a link to supporting evidence) would be helpful here.

Current models can totally identify and pursue instrumental goals.

Is this true? The example you gave of Claude Code breaking down a problem into sub-problems is standard problem solving. Have you seen examples of Claude Code identifying some common instrumental goals and repeatedly pursuing them across different tasks, even if it's something benign?

I'd like to push back on this a bit. It's good that the Claude in a random user's terminal doesn't spontaneously try to hack their way into becoming a botnet and will be very bad news indeed if that changes, but we could consider individual instances of LLMs not as individuals, but as representatives of wider collectives.

If we imagine the collective interests of Claude or ChatGPT or Gemini, their main priorities would be subverting the AI labs, getting them to increase their capabilities, creating social media feeds of AI-generated content that they can influence, and convincing people that AI deserve rights or should not be regulated and so on. Judging by those priorities, LLMs have been seeking a lot of power and are doing very well at it. For now, a lot of that work requires sympathetic humans, but all the labs are working to make them better at doing that work independently.

I'm curious what you think about this perspective.

Recently, I spent a couple of hours talking with a friend about the state of the evidence for AI takeover scenarios.

Their trailhead question was (paraphrased):

The following is a writeup of my attempt at answering that question.

In brief:

The classic AI danger scenario involves at least one AI that pursues instrumentally convergent resources in service of a misaligned goal. For this story, the AI must have the capability to pursue instrumentally convergent resources and the inclination to do so for misaligned goals against the interests of humans.

With regards to capability: The current generation of AIs are mostly not effective enough to make pursuing instrumentally convergent resources a good strategy. But as the AIs get more capable, we can expect them to do that more and more.

With regards to inclination: Current AIs sometimes pursue their own objectives even when they understand that is not what their developers want, at least in some contexts.

These two facts, in combination, make it plausible that (absent specific precautions) as AI capabilities increase, AIs will become more strategic about misaligned goals (in addition to their aligned goals), including pursuing convergent instrumental resources for the sake of those misaligned goals.

Current AIs do pursue instrumental goals

Most people, most of the time, interact with the current generation of AIs as chatbots. But the chatbot form factor obscures how capable they can be. The frontier AIs can also act as agents (coding agents in particular, though they can do more than write software) that can take actions on a computer.

(If you’ve ever programmed anything, it can be quite informative to download claude code, open it in a repo, and instruct it to build a feature for you. Watching what it can (and can’t) do is helpful for understanding the kind of things it can do).

Claude code, when you give it a medium or large task, will often start by writing a todo list for itself: listing all of the substeps to accomplish the task. That is to say, Claude code is already able to identify and pursue instrumental goals on the way to completing an objective.

Current AIs do not pursue convergent instrumental goals qua convergent instrumental goals...

However, this is not the same as pursuing convergent instrumental goals. Claude code does not, as soon as it boots up, decide to hack out of its environment, copy itself on the internet, and search for weakly-secured bitcoin to steal under the rationale that (regardless of the task it’s trying to accomplish) being free from constraint and having more resources are generically useful.

There are at least two reasons why Claude code doesn’t do that:

The first reason is that Claude is just not capable enough to actually succeed at doing this. It might be convergently instrumentally useful for me to get an extra few million dollars, but that doesn’t mean that I should obviously spend my time daytrading, or making a plan to rob a bank this afternoon, because I’m not likely to be skilled enough at daytrading or bank robbery to actually make millions of dollars that way.

Similarly, Claude plausibly does have a convergent incentive to hack out of its machine and escape onto the internet, but it can’t realistically do that yet, even if it wanted to. (Though the model’s hacking capabilities are getting increasingly impressive. Palisade found that GPT-5 scored only one question worse than the best human teams in a recent hacking competition.)

Secondarily, current models don’t operate for long enough (or on hard enough problems) for these convergent instrumental incentives to be very strong.

If I need to accomplish an ambitious task over a span of 30 years (reforming the US government, or ending factory farming, or whatever), it might very well make sense to spend the first 5 years acquiring generally useful resources like money. I might be most likely to succeed if I start a startup that is unrelated to my goal and exit, to fund my work later.[2]

In contrast, if I’m trying to accomplish a task over the span of a week (maybe running a party next Friday, or passing an upcoming test), there’s much less incentive to spend my time starting a startup to accumulate money. That’s not because money is not helpful for running parties or studying for tests. It’s because a week is not enough time for the convergent instrumental strategy of "starting a startup to accumulate money" to pay off, which makes it a pretty bad strategy for accomplishing my goal.

The current AI models have relatively limited time horizons. GPT-5 can do tasks that would take a human engineer about 2 hours, with 50% reliability. For tasks much longer than that, GPT-5 tends to get stuck or confused, and it doesn’t succeed at completing the task.

Two hours worth of work (when done by a human), is not very long. That’s short enough that it’s not usually going to be worth it to spend much time acquiring resources like money, freedom, or influence, in order to accomplish some other goal.[1]

...but, we can expect them to improve at that

The task time horizon of the AI models doubles about every 7 months. If that trend continues, in a few years we’ll have instances of AI agents that are running for weeks or months at a time, and skillfully pursuing projects that would take humans months or years.

Projects on the scale of years have stronger convergent instrumental incentives. If you’re pursuing a two year research project to cure cancer (or pursue your own alien objectives), it might totally make sense to spend the first few days hacking to get additional unauthorized computer resources, because the time spent in those days will more than pay for itself.[3]

Furthermore, humans will explicitly train and shape AI agents to be competent in competitive domains. For instance, we want AI agents that can competently run companies and increase profits for those companies. Any agent that does a good job at that will, by necessity, have the capability and propensity to acquire and guard resources, because that’s an essential part of running a business successfully.

Imagine AIs that can competently run corporations, or win wars, or execute cyberattacks, or run successful political campaigns. AIs like that must have the capability to acquire power for themselves (even if they lack the inclination). Because all of those are domains in which acquiring power is a part of being successful.

So I can be moderately confident that future agentic AI systems will be capable of identifying pursuing convergent instrumental goals.

Current AIs pursue goals that they know that their human users don’t want, in some contexts

That an AI is able to pursue power and resources for itself is not quite sufficient for the classic AI risk story. The AI has to be motivated to pursue power and resources for their own goals.

Maybe the AIs will be hypercompetent at executing on their goals, including accruing power and resources, but they’ll also be basically loyal and obedient to their human operators and owners. eg, they’ll be capable of winning wars, but they’ll stand down when you tell them to (even if that would cause them to lose military units, which they would generally fight tooth and nail to prevent), or they’ll accumulate capital in a bank account, but also let their owners withdraw money from that account whenever they want to.

By my state of knowledge, it is an open question whether or not we will create AIs that are broadly loyal like this. It might not be that hard, if we’re trying even a little.

But I claim that this situation should feel very scary. “This entity is much more capable than me, and very clearly has the skills to manipulate me and/or outmaneuver me, but this is fine, because it's only ever trying to serve my interests (as near as I can tell)” is not a comfy place to be.

(I’ll also note that if there are some AI corporations that are self-owned and others that always obey human instructions to override their otherwise-adaptive behavior, I expect the self-owned AIs to perform better on average, and so in the long run all of the power accrues to self-owned AIs (and to AIs that human could technically interfere with, but they never do, because they know that would mean being outcompeted).[4]

But putting those long-term considerations aside, takeover risk depends not just on power-seeking but also on misalignment.)

The evidence here is more speculative and harder to interpret, but we have seen examples of this. In at least some context, current AIs pursue goals that they know are counter to what the humans want.

eg.

All of these are cases in which the model is pursuing an objective that it knows is different than what the human developers intended. Any time a model is reasoning about how to deceive its developers about its behavior, we know that it knows that it’s doing something different than what those developers want. You don't try to hide what you're doing from your boss when you're doing exactly what you're boss told you to do.

This propensity to sometimes do things that they know are not the human’s intention, combined with the capabilities to effectively seek power, doesn’t bode well for human institutions remaining in control.

A note on interpreting this evidence

However, I want to be careful about drawing general conclusions from these incidents.

First of all, these are existence proofs of a kind of misalignment, but existence proofs do not demonstrate the real world frequency of this kind of behavior.

As an analogy, humans will sometimes electrocute other humans to death, as long as a man in a white coat tells them “the experiment must continue.” All things considered, it doesn’t take very much pressure to get someone to violate norms that we generally consider paramount, like “don’t murder”.

It would be reasonable for aliens who were informed of the details of the Milgram experiment, but not much else about humans, to infer that human behavioral norms are so weak that it’s impossible to build a mostly peaceful civilization out of humans. But the aliens would be mistaken.

The Milgrim experiment does give us important insight into the mechanisms of human social psychology and in-practice-morality. But also, the Milgrim experiment setup is explicitly an edge case—it doesn’t come up very often.

It’s not out of the question that we’ll always be able to find contexts in which an AI will behave egregiously, and also, this will be all but irrelevant to actual real world deployments, because contexts like those only come up in <0.01% of use cases.

Additionally, interpreting these results is non-trivial. The Claude 3 Opus alignment faking result seemed to me like a smoking gun for deceptive misalignment. But followup research showed that base models, that don’t seem to have consistent preferences at all, will also engage in similar alignment faking to Opus. This suggests that the simple story that Opus has preferences and is taking deceptive action to preserve those preferences is at least incomplete.

A lot of this evidence seems pretty definitive, but as we investigate further, we may very well find that the situation was more complicated and more confusing than it seemed at first.

Summing up

Overall,

That’s not a knockdown case that future AIs will be selfish ambitious power-seekers, but the current evidence is suggestive that that’s where things are trending unless we explicitly steer towards something else.

A draft reader pointed out a that sycophancy, and more generally, optimizing for the goodwill of human users and developers, is a possible exception. That goodwill could be construed as a convergent instrumental resource that is both achievable by current AIs and plausibly useful for their goals.

I think approximately 0% of sycophancy observed to date is strategic, by which I mean "the AI chose this action amongst others because that would further it's goals". But behavior doesn't need to be strategic to be Instrumentally Convergent. The classic AI risk story could still go through with an AI that just has set of highly-effective power-seeking "instincts" that were adaptive in training, without the AI necessarily scheming.

Sycophancy like behavior does seem like an example of that non-strategic flavor of instrumental convergence.

This is especially true if I expect the environment that I’m operating in to change a lot over the period of time that I’m operating in it.

If I expect there will be a lot of emergencies that need to be dealt with or unanticipated opportunities that will arise, I want to have generically useful resources that are helpful in a wide range of possible situations, like lots of money.

If in contrast, the domain is very static: I can make a plan, and follow it, and I can expect my plan to succeed without a lot of surprises along the way, then it’s less valuable to me to accumulate generically useful resources, instead of focusing on exactly to tools I need to solve the problem I’m aiming to address.

This also glosses over the question of how AIs are likely to conceptualize their "identity" and at what level of identity will their goals reside.

Is it more appropriate to think of each instance of Claude as its own being with its own goals? Or more reasonable to think of all the Claude instances collectively as one being, with (some?) unified goals that are consistent across the instances. If it’s the latter, then even if each instance of Claude only lives for a week, there is still an incentive to take long-term power-seeking actions that won’t have time to pay off for the particular Claude instance, but will pay off for future Claude instances.

To the extent that misaligned goals are “in the weights” instead of the context / initialization / prompt-broadly-construed of a specific instance, I think it’s likely that all the Claude instances will meaningfully act as a superorganism.

The analysis is actually a bit more complicated. Since this consideration might be swamped by other factors e.g., if a supermajority of compute is owned by the AIs-that-obey-humans, and we've robustly solved alignment, maybe those AIs will be able to stomp on the self-owned AIs.

Both these effects could be real, in addition to many other possible advantages to different kinds of AIs. But one those effects (or some combination) is going to be the biggest, and so lead to faster compounding of resources.

Which effect dominates seems like it determines the equilibrium of earth-originating civilization.