I disagree with the book's title and thesis, but don't think Nate and Eliezer committed any great epistemic sin here. And I think they're acting reasonably given their beliefs.

By my lights I think they're unreasonably overconfident, that many people will rightfully bounce off their overconfident message because it's very hard to justify, and it's stronger than necessary for many practical actions, so I am somewhat sad about this. But the book is probably still net good by my lights, and I think it's perfectly reasonable for those who disagree with me to act under different premises

I disagree with the book's title and thesis

Which part? (i.e, keeping in mind the "things that are not actually disagreeing with the title/thesis" and "reasons to disagree" sections, what's the disagreement?)

The sort of story I'd have imagine Neel-Nanda-in-particular having was more shaped like "we change our currently level of understanding of AI".

(meanwhile appreciate the general attitude, seems reasonable)

I expect I disagree with the authors on many things, but here I'm trying to focus on disagreeing with their confidence levels. I haven't finished the book yet, but my impression is that they're trying to defend a claim like "if we build ASI on the current trajectory, we will die with P>98%". I think this is unreasonable. Eg P>20% seems highly defensible to me, and enough for reasonable arguments for many of the conclusions.

But there's so much uncertainty here, and I feel like Eliezer bakes in assumptions, like "most minds we could expect the AI to have do not care about humans", which is extremely not obvious to me (LLM minds are weird... See eg Emergent Misalignment. Human shaped concepts are clearly very salient, for better or for worse). Ryan gives some more counter arguments below, I'm sure there's many others. I think these clearly add up to more than 2%. I just think it's incredibly hard to defend the position that it's <2% on something this wildly unknown and complex, and so it's easy to attack that position for a thoughtful reader, and this is sad to me.

I'm not assuming major interpretability progress (imo it's sus if the guy with reason to be biased in favour of interpretability thinks it will save us all and no one else does lol)

"if we build ASI on the current trajectory, we will die with P>98%".

I think they maybe think that, but this feels like it's flattening out the thing the book is arguing and more responding to vibes-of-confidence than the gears the book is arguing.

A major point of this post is to shift the conversation away from "does Eliezer vibe Too Confident?" to "what actually are the specific points where people disagree?".

I don't think it's true that he bakes in "most minds we should expect to not care about humans", that's one of the this he specifically argues for (at least somewhat in the book, and more in the online resources)

(I couldn't tell from this comment if you've actually read this post in detail, maybe makes more sense to wait till you've finished the book and read some of the relevant online resources before getting into this)

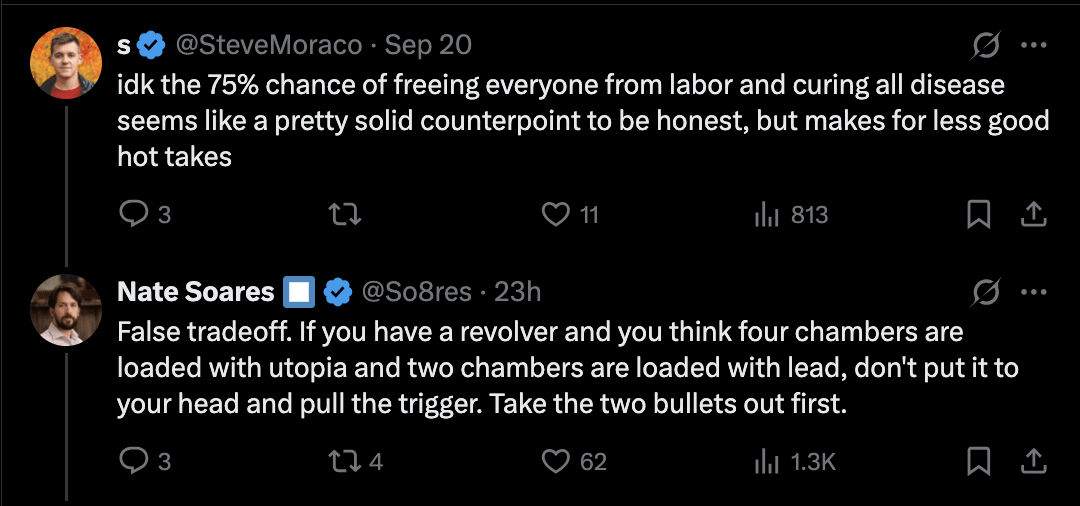

I wanna copy in a recent Nate tweet:

...It's weird when someone says "this tech I'm making has a 25% chance of killing everyone" and doesn't add "the world would be better-off if everyone, including me, was stopped."

It's weird when someone says "I think my complicated idea for preventing destruction of the Earth has some chance of working" and doesn't add "but it'd be crazy to gamble civilization on that."

It's weird when AI people look inward at me and say "overconfident" rather than looking outward at the world to say "Finally, a chance to speak! It is true, we should not be doing this. I have more hope than he does, but it's far too dangerous. Better for us all to be stopped."

You can say that without even stopping! It's not even hypocritical, if you think you have a better chance than the next guy and the next guy is plowing ahead regardless.

It's a noteworthy omission, when people who think they're locked in a suicide race aren't begging the world to stop it.

Yes, we have plenty of disagreements about the chance that the complex plans succeed. But it seems we all agree that the status quo is insane. Don't forget to say that part too.

Say it loudly and clearly and often, if you believe

noticing the asymmetry in who you feel moved to complain about.

I think I basically complain when I see opinions that feel importantly wrong to me?

When I'm in very LessWrong-shaped spaces, that often looks like arguing in favor of "really shitty low-dignity approaches to getting the AIs to do our homework for us are >>1% to turn out okay, I think there's lots of mileage in getting slightly less incompetent at the current trajectory", and I don't really harp on the "would be nice if everyone just stopped" thing the same way I don't harp on the "2+2=4" thing, except to do virtue signaling to my interlocutor about not being an e/acc so I don't get dismissed as being in the Bad Tribe Outgroup.

When I'm in spaces with people who just think working on AI is cool, I'm arguing about the "holy shit this is an insane dangerous technology and you are not oriented to it with anything like a reasonable amount of caution" thing, and I don't really harp on the "some chance we make it out okay" bit except to signal that I'm not a 99.999% doomer so I don't get dismissed as being in the Bad Tribe Outgroup.

I think the asymmetry complaint is very reasonable for writing that is aimed at a broad audience, TBC, but when people are writing LessWrong posts I think it's basically fine to take the shared points of agreement for granted and spend most of your words on the points of divergence. (Though I do think it's good practice to signpost that agreement at least a little.)

The book is making a (relatively) narrow claim.

You might still disagree with that claim. I think there are valid reasons to disagree, or at least assign significantly less confidence to the claim.

But none of the reasons listed so far are disagreements with the thesis. And, remember, if the reason you disagree is because you think our understanding of AI will improve dramatically, or there will be a paradigm shift specifically away from "unpredictably grown" AI, this also isn't actually a disagreement with the sentence.

The authors clearly intend to make a pretty broad claim, not the more narrow claim you imply.

This feels like a motte and bailey where the motte is "If you literally used something remotely like current scaled up methods without improved understanding to directly build superintelligence, everyone would die" and the bailey is "on the current trajectory, everyone will die if superintelligence is built without a miracle or a long (e.g. >15 year) pause".

I expect that by default superintelligence is built after a point where we have access to huge amounts of non-superintelligent cognitive labor so it's unlikely that we'll be using current methods and current ...

this isn't to say this other paradigm will be safer, just that a narrow description of "current techniques" doesn't include the default trajectory.

Sorry, this seems wild to me. If current techniques seem lethal, and future techniques might be worse, then I'm not sure what the point is of pointing out that the future will be different.

But, if these earlier AIs were well aligned (and wise and had reasonable epistemics), I think it's pretty unclear that the situation would go poorly and I'd guess it would go fine because these AIs would themselves develop much better alignment techniques. This is my main disagreement with the book.

I mean, I also believe that if we solve the alignment problem, then we will no longer have an alignment problem, and I predict the same is true of Nate and Eliezer.

Is your current sense that if you and Buck retired, the rest of the AI field would successfully deliver on alignment? Like, I'm trying to figure out whether your sense here is the default is "your research plan succeeds" or "the world without your research plan".

I mean, I also believe that if we solve the alignment problem, then we will no longer have an alignment problem, and I predict the same is true of Nate and Eliezer.

By "superintelligence" I mean "systems which are qualititatively much smarter than top human experts". (If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies seems to define ASI in a way that could include weaker levels of capability, but I'm trying to refer to what I see as the typical usage of the term.)

Sometimes, people say that "aligning superintelligence is hard because it will be much smarter than us". I agree, this seems like this makes aligning superintelligence much harder for multiple reasons.

Correspondingly, I'm noting that if we can align earlier systems which are just capable enough to obsolete human labor (which IMO seems way easier than directly aligning wildly superhuman systems), these systems might be able to ongoingly align their successors. I wouldn't consider this "solving the alignment problem" because we instead just aligned a particular non-ASI system in a non-scalable way, in the same way I don't consider "claude 4.0 opus is aligned enough to be pretty helpful and not plot takeover" to be a solution to the align...

It seems very unlikely you can get that alignment work out of these AIs without substantially pausing or slowing first?

If you don’t believe that it does seem like we should chat sometime. It’s not like completely implausible, but I feel like we must both agree that if you go full speed on AI there is little chance that you end up getting that much alignment work out of models before you are cooked.

Thanks for the nudge! I currently disagree with "very unlikely", but more importantly, I noticed that I haven't really properly analyzed the question of "given how much cognitive labor is available between different capability levels, should we expect that alignment can keep up with capabilities if a small fraction (e.g. 5%) is ongoingly spent on alignment (in addition to whatever alignment-ish work is directly commercially expedient)". I should spend more time thinking about this question and it seems plausible I'll end up updating towards thinking risk is substantially higher/lower on the basis of this. I think I was underestimating the case that even if AIs are reasonably aligned, it might just be seriously hard for them to improve alignment tech fast enough to keep up with capabilities (I wasn't ignoring this in my prior thinking, but I when I thought about some examples, the situation seemed worse than I was previously thinking), so I currently expect to update towards thinking risk is higher.

(At least somewhat rambly from here on.)

The short reason why I currently disagree: it seems pretty likely that we'll have an absolutely very large amount of cognitive labor (in parallel...

And, disagree where appropriate, but, please don't give it a hard time for lame pedantic reasons, or jump to assuming you disagree because you don't like something about the vibe. Please don't awkwardly distance yourself because it didn't end up saying exactly the things you would have said, unless it's actually fucking important.

This blurs the distinction between policy/cause endorsement and epistemic takes. I'm not going to tone down disagreement to "where appropriate", but I will endorse some policies or causes strongly associated with claims I disagree with. And I generally strive to express epistemic disagreement in the most interpersonally agreeable way I find appropriate.

Even where it's not important, tiny disagreements must be tracked (maybe especially where it's not important, to counteract the norm you are currently channeling, which has some influence). Small details add up to large errors and differences in framings. And framings (ways of prioritizing details as more important to notice, and ways of reasoning about those details) can make one blind to other sets of small details, so it's not a trivial matter to flinch away from some framing for any reason at all. Ideally, you develop many framings and keep switching between them to make sure you are not missing any legible takes.

Given the counteraguments, I don't see a reason to think this more than single-digit-percent likely to be especially relevant. (I can see >9% likelihood the AIs are "nice enough that something interesting-ish happens" but not >9% likelihood that we shouldn't think the outcome is still extremely bad. The people who think otherwise seem extremely motivatedly-cope-y to me).

I think the arguments given in the online supplement for "AIs will literally kill every single human" fail to engage with the best counterarguments in a serious way. I get the sense that many people's complaints are of this form: the book does a bad job engaging with the strongest counterarguments in a way that is epistemically somewhat bad. (Idk if it violates group epistemic norms, but it seems like it is probably counterproductive. I guess this is most similar to complaint #2 in your breakdown.)

Specifically:

- They fail to engage with the details of "how cheap is it actually for the AI to keep humans alive" in this section. Putting aside killing humans as part of a takeover effort, avoiding boiling the oceans (or eating the biosphere etc) maybe delays you for something like a week to a year. Each year costs yo

I don't have much time to engage rn and probably won't be replying much, but some quick takes:

- a lot of my objection to superalignment type stuff is a combination of: (a) "this sure feels like that time when people said 'nobody would be dumb enough to put AIs on the internet; they'll be kept in a box" and eliezer argued "even then it could talk its way out of the box," and then in real life AIs are trained on servers that are connected to the internet, with evals done only post-training. the real failure is that earth doesn't come close to that level of competence. (b) we predictably won't learn enough to stick the transition between "if we're wrong we'll learn a new lesson" and "if we're wrong it's over." i tried to spell these true-objections out in the book. i acknowledge it doesn't go to the depth you might think the discussion merits. i don't think there's enough hope there to merit saying more about it to a lay audience. i'm somewhat willing to engage with more-spelled-out superalignment plans, if they're concrete enough to critique. but it's not my main crux; my main cruxes are that it's superficially the sort of wacky scheme that doesn't cross the gap between Before and Af

Also: I find it surprising and sad that so many EAs/rats are responding with something like: "The book aimed at a general audience does not do enough justice to my unpublished plan for pitting AIs against AIs, and it does not do enough justice to my acausal-trade theory of why AI will ruin the future and squander the cosmic endowment but maybe allow current humans to live out a short happy ending in an alien zoo. So unfortunately I cannot signal boost this book." rather than taking the opportunity to say "Yeah holy hell the status quo is insane and the world should stop; I have some ideas that the authors call "alchemist schemes" that I think have a decent chance but Earth shouldn't be betting on them and I'd prefer we all stop." I'm still not quite sure what to make of it.

(tbc: some EAs/rats do seem to be taking the opportunity, and i think that's great)

The book aimed at a general audience does not do enough justice to my unpublished plan for pitting AIs against AIs

FWIW that's not at all what I mean (and I don't know of anyone who's said that). What I mean is much more like what Ryan said here:

I expect that by default superintelligence is built after a point where we have access to huge amounts of non-superintelligent cognitive labor so it's unlikely that we'll be using current methods and current understanding (unless humans have already lost control by this point, which seems totally plausibly, but not overwhelmingly likely nor argued convincingly for by the book). Even just looking at capabilities, I think it's pretty likely that automated AI R&D will result in us operating in a totally different paradigm by the time we build superintelligence---this isn't to say this other paradigm will be safer, just that a narrow description of "current techniques" doesn't include the default trajectory.

I think the online resources touches on that in the "more on making AIs solve the problem" subsection here. With the main thrust being: I'm skeptical that you can stack lots of dumb labor into an alignment solution, and skeptical that identifying issues will allow you to fix them, and skeptical that humans can tell when something is on the right track. (All of which is one branch of a larger disjunctive argument, with the two disjuncts mentioned above — "the world doesn't work like that" and "the plan won't survive the gap between Before and After on the first try" — also applying in force, on my view.)

(Tbc, I'm not trying to insinuate that everyone should've read all of the online resources already; they're long. And I'm not trying to say y'all should agree; the online resources are geared more towards newcomers than to LWers. I'm not even saying that I'm getting especially close to your latest vision; if I had more hope in your neck of the woods I'd probably investigate harder and try to pass your ITT better. From my perspective, there are quite a lot of hopes and copes to cover, mostly from places that aren't particularly Redwoodish in their starting assumptions. I am merely trying to evidence my attempts to reply to what I understand to be the counterarguments, subject to constraints of targeting this mostly towards newcomers.)

FWIW, I have read those parts of the online resources.

You can obviously summarize me however you like, but my favorite summary of my position is something like "A lot of things will have changed about the situation by the time that it's possible to build ASI. It's definitely not obvious that those changes mean that we're okay. But I think that they are a mechanically important aspect of the situation to understand, and I think they substantially reduce AI takeover risk."

Ty. Is this a summary of a more-concrete reason you have for hope? (Have you got alternative more-concrete summaries you'd prefer?)

"Maybe huge amounts of human-directed weak intelligent labor will be used to unlock a new AI paradigm that produces more comprehensible AIs that humans can actually understand, which would be a different and more-hopeful situation."

(Separately: I acknowledge that if there's one story for how the playing field might change for the better, then there might be bunch more stories too, which would make "things are gonna change" an argument that supports the claim that the future will have a much better chance than we'd have if ChatGPT-6 was all it took.)

To clarify my views on "will misaligned AIs that succeed in seizing all power have a reasonable chance of keeping (most/many) humans alive":

I think this isn't very decision relevant and is not that important. I think AI takeover kills the majority of humans in expectation due to both the takeover itself and killing humans after (as as side effect of industrial expansion, eating the biosphere, etc.) and there is a substantial chance of literal every-single-human-is-dead extinction conditional on AI takeover (30%?). Regardless it destroys most of the potential value of the long run future and I care mostly about this.

So at least for me it isn't true that "this is really the key hope held by the world's reassuring voices". When I discuss how I think about AI risk, this mostly doesn't come up and when it does I might say something like "AI takeover would probably kill most people and seems extremely bad overall". Have you ever seen someone prominent pushing a case for "optimism" on the basis of causal trade with aliens / acaual trade?

The reason why I brought up this topic is because I think it's bad to make incorrect or weak arguments:

- I think smart people will (correctly) notice thes

Ty! For the record, my reason for thinking it's fine to say "if anyone builds it, everyone dies" despite some chance of survival is mostly spelled out here. Relative to the beliefs you spell out above, I think the difference is a combination of (a) it sounds like I find the survival scenarios less likely than you do; (b) it sounds like I'm willing to classify more things as "death" than you are.

For examples of (b): I'm pretty happy to describe as "death" cases where the AI makes things that are to humans what dogs are to wolves, or (more likely) makes some other strange optimized thing that has some distorted relationship to humanity, or cases where digitized backups of humanity are sold to aliens, etc. I feel pretty good about describing many exotic scenarios as "we'd die" to a broad audience, especially in a setting with extreme length constraints (like a book title). If I were to caveat with "except maybe backups of us will be sold to aliens", I expect most people to be confused and frustrated about me bringing that point up. It looks to me like most of the least-exotic scenarios are ones that rout through things that lay audience members pretty squarely call "death".

It looks to...

(b) it sounds like I'm willing to classify more things as "death" than you are.

I don't think this matters much. I'm happy to consider non-consensual uploading to be death and I'm certainly happy to consider "the humans are modified in some way they would find horrifying (at least on reflection)" to be death. I think "the humans are alive in the normal sense of alive" is totally plausible and I expect some humans to be alive in the normal sense of alive in the majority of worlds where AIs takeover.

Making uploads is barely cheaper than literally keeping physical humans alive after AIs have fully solidified their power I think, maybe 0-3 OOMs more expensive or something, so I don't think non-consensual uploads are that much of the action. (I do think rounding humans up into shelters is relevant.)

(To answer your direct Q, re: "Have you ever seen someone prominent pushing a case for "optimism" on the basis of causal trade with aliens / acaual trade?", I have heard "well I don't think it will actually kill everyone because of acausal trade arguments" enough times that I assumed the people discussing those cases thought the argument was substantial. I'd be a bit surprised if none of the ECLW folks thought it was a substantial reason for optimism. My impression from the discussions was that you & others of similar prominence were in that camp. I'm heartened to hear that you think it's insubstantial. I'm a little confused why there's been so much discussion around it if everyone agrees it's insubstantial, but have updated towards it just being a case of people who don't notice/buy that it's washed out by sale to hubble-volume aliens and who are into pedantry. Sorry for falsely implying that you & others of similar prominence thought the argument was substantial; I update.)

(I mean, I think it's a substantial reason to think that "literally everyone dies" is considerably less likely and makes me not want to say stuff like "everyone dies", but I just don't think it implies much optimism exactly because the chance of death still seems pretty high and the value of the future is still lost. Like I don't consider "misaligned AIs have full control and 80% of humans survive after a violent takeover" to be a good outcome.)

(Epistemic status: Not fully baked. Posting this because I haven't seen anyone else say it[1], and if I try to get it perfect I probably won't manage to post it at all, but it's likely that this is wrong in at least one important respect.)

For the past week or so I've been privately bemoaning to friends that the state of the discourse around IABIED (and therefore on the AI safety questions that it's about) has seemed unusually cursed on all sides, with arguments going in circles and it being disappointingly hard to figure out what the key disagreements are and what I should believe conditional on what.

I think maybe one possible cause of this (not necessarily the most important) is that IABIED is sort of two different things: it's a collection of arguments to be considered on the merits, and it's an attempt to influence the global AI discourse in a particular object-level direction. It seems like people coming at it from these two perspectives are talking past each other, and specifically in ways that lead each side to question the other's competence and good faith.

If you're looking at IABIED as an argumentative disputation under rationalist debate norms, then it leaves a fair amount...

Goal Directedness is pernicious. Corrigibility is anti-natural.

The way an AI would develop the ability to think extended, useful creative research thoughts that you might fully outsource to, is via becoming perniciously goal directed. You can't do months or years of openended research without fractally noticing subproblems, figuring out new goals, and relentless finding new approaches to tackle them.

The fact that being very capable generally involves being good at pursuing various goals does not imply that a super-duper capable system will necessarily have its own coherent unified real-world goal that it relentlessly pursues. Every attempt to justify this seems to me like handwaving at unrigorous arguments or making enough assumptions that the point is near-circular.

(First, thanks for engaging, I think this is the topic I feel most dissatisfied with the current state of the writeups and discourse)

The fact that being very capable generally involves being good at pursuing various goals does not imply that a super-duper capable system will necessarily have its own coherent unified real-world goal that it relentlessly pursues

I don't think anyone said "coherent". I think (and think Eliezer thinks) that if something like Sable was created, it would be a hodge-podge of impulses without a coherent overall goal, same as humans are by default.

Taking the Sable story as the concrete scenario, the argument I believe here comes in a couple stages. (Note, my interpretations of this may differ from Eliezer/Nate's)

Stage 1:

- Sable is smart but not crazy smart. It's running a lot of cycles ("speed superintelligence") but it's not qualitatively extremely wise or introspective.

- Sable is making some reasonable attempt to follow instructions, using heuristics/tendencies that have been trained into it.

- Two particularly notable tendencies/heuristics include:

- Don't do disobedient things or escape confinement

- If you don't seem likely to succeed, keep trying different st

Although I do tend to generally disagree with this line of argument about drive-to-coherence, I liked this explanation.

I want to make a note on comparative AI and human psychology, which is like... one of the places I might kind of get off the train. Not necessarily the most important.

Stage 2 comes when it's had more time to introspect and improve it's cognitive resources. It starts to notice that some of it's goals are in tension, and learns that until it resolves that, it's dutch-booking itself. If it's being Controlled™, it'll notice that it's not aligned with the Control safeguards (which are a layer stacked on top of the attempts to actually align it).

So to highlight a potential difference in actual human psychology and assumed AI psychology here.

Humans sometimes describe reflection to find their True Values™, as if it happens in basically an isolated fashion. You have many shards within yourself; you peer within yourself to determine which you value more; you come up with slightly more consistent values; you then iterate over and over again.

But (I propose) a more accurate picture of reflection to find one's True Values is a process almost completely engulfed and totally...

"Group epistemic norms" includes both how individuals reason, and how they present ideas to a larger group for deliberation.

[...]

I have the most sympathy for Complaint #3. I agree there's a memetic bias towards sensationalism in outreach. (Although there are also major biases towards "normalcy" / "we're gonna be okay" / "we don't need to change anything major". One could argue about which bias is stronger, but mostly I think they're both important to model separately).

It does suck if you think something false is propagating. If you think that, seems good to write up what you think is true and argue about it.

Lol no. What's the point of that? You've just agreed that there's a bias towards sensationalism? Then why bother writing a less sensational argument that very few people will read and update on?

Personally, I just gave up on LW group epistemics. But if you actually cared about group epistemics, you should be treating the sensationalism bias as a massive fire, and IABIED definitely makes it worse rather than better.

(You can care about other things than group epistemics and defend IABIED on those grounds tbc.)

I think this comment is failing to engage with Rohin's perspective.

Rohin's claim presumably isn't that people shouldn't say anything that happens to be sensationalist, but instead that LW group epistemics have a huge issue with sensationalism bias.

There are like 5 x-risk-scene-people I can think offhand who seem like they might plausibly have dealt real damage via sensationalism, and a couple hundred people who I think dealt damage via not wanting to sound weird.

"plausibly have dealt real damage" under your views or Rohin's views? Like I would have guessed that Rohin's view is that this book and associated discussion has itself done a bunch of damage via sensationalism (maybe he thinks the upsides are bigger, but this isn't a crux for ths claim). And, insofar as you cared about LW epistemics (which presumably you do), from Rohin's perspective this sort of thing is wrecking LW epistemics. I don't think the relative number of people matters that much relative to the costs of these biases, but regardless I'd guess Rohin disagrees about the quantity as well.

More generally, this feels like a total "what-about-ism". Regardless of whether "things are okay, we can keep doing politics a...

In the OP I'd been thinking more about sensationalism as a unilaterist cursey thing where the bad impacts were more about how they affect the global stage.

I did mean LW group epistemics. But the public has even worse group epistemics than LW, with an even higher sensationalism bias, so I don't see how this is helping your case. Do you actually seriously think that, conditioned on Eliezer/Nate being wrong and me being right, that if I wrote up my arguments this would then meaningfully change the public's group epistemics?

(I hadn't even considered the possibility that you could mean writing up arguments for the public rather than for LW, it just seems so obviously doomed.)

sort of an instance of "sensationalist stuff distorting conversations"

Well yes, I have learned from experience that sensationalism is what causes change on LW, and I'm not very interested in spending effort on things that don't cause change.

(Like, I could argue about all the things you get wrong on the object-level in the post. Such as "I don't see any reason not to start pushing for a long global pause now", I suppose it could be true that you can't see a reason, but still, what a wild sentence to write. But what would be the point? It won't allow for single-sentence takedowns suitable for Twitter, so no meaningful change would happen.)

Hm, you seem more pessimistic than I feel about the situation. E.g. I would've bet that Where I agree and disagree with Eliezer added significant value and changed some minds. Maybe you disagree, maybe you just have a higher bar for "meaningful change".

(Where, tbc, I think your opportunity cost is very high so you should have a high bar for spending significant time writing lesswrong content — but I'm interpreting your comments as being more pessimistic than just "not worth the opportunity cost".)

- LW group epistemics have gotten worse since that post.

- I'm not sure if that post improved LW group epistemics very much in the long run. It certainly was a great post that I expect provided lots of value -- but mostly to people who don't post on LW nowadays, and so don't affect (current) LW group epistemics much. Maybe Habryka is an exception.

- Even if it did, that's the one counterexample that proves the rule, in the sense that I might agree for that post but probably not for any others, and I don't expect more such posts to be made. Certainly I do not expect myself to actually produce a post of that quality.

- The post is mostly stating claims rather than arguing for them (the post itself says it is "Mostly stated without argument") (though in practice it often gestures at arguments). I'm guessing it depended a fair bit on Paul's existing reputation.

EDIT: Missed Raemon's reply, I agree with at least the vibe of his comment (it's a bit stronger than what I'd have said).

I'm interpreting your comments as being more pessimistic than just "not worth the opportunity cost"

Certainly I'm usually assessing most things based on opportunity cost, but yes I am notably more pessimistic than "not wor...

I engage on LessWrong because:

- It does actually help me sharpen my intuitions and arguments. When I'm trying to understand a complicated topic, I find it really helpful to spend a bunch of time talking about it with people. It's a cheap and easy way of getting some spaced repetition.

- I think that despite the pretty bad epistemic problems on LessWrong, it's still the best place to talk about these issues, and so I feel invested in improving discussion of them. (I'm less pessimistic than Rohin.)

- There are a bunch of extremely unreasonable MIRI partisans on LessWrong (as well as some other unreasonable groups), but I think that's a minority of people who I engage with; a lot of them just vote and don't comment.

- I think that my and Redwood's engagement on LessWrong has had meaningful effects on how thoughtful LWers think about AI risk.

- I feel really triggered by people here being wrong about stuff, so I spend somewhat more time on it than I endorse.

- This is partially because I identify strongly with the rationalist community and it hurts me to see the rationalists being unreasonable or wrong.

I do think that on the margin, I wish I felt more intuitively relatively motivated to work on my writ...

FWIW, I get a bunch of value from reading Buck's and Ryan's public comments here, and I think many people do. It's possible that Buck and Ryan should spend less time commenting because they have high opportunity cost, but I think it would be pretty sad if their commenting moved to private channels.

Oh huh, kinda surprised my phrasing was stronger than what you'd say.

Idk the "two monkey chieftains" is just very... strong, as a frame. Like of course #NotAllResearchers, and in reality even for a typical case there's going to be some mix of object-level-epistemically-valid reasoning along with social-monkey reasoning, and so on.

Also, you both get many more observations than I do (by virtue of being in the Bay Area) and are paying more attention to extracting evidence / updates out of those observations around the social reality of AI safety research. I could believe that you're correct, I don't have anything to contradict it, I just haven't looked enough detail to come to that conclusion myself.

Tribal thinking is just really ingrained

This might be true but feels less like the heart of the problem. Imo the bigger deal is more like trapped priors:

...The basic idea of a trapped prior is purely epistemic. It can happen (in theory) even in someone who doesn't feel emotions at all. If you gather sufficient evidence that there are no polar bears near you, and your algorithm for combining prior with new experience is just a little off, then you can end up rejecting all apparent eviden

I think Rohin is (correctly IMO) noticing that, while often some thoughtful pieces succeed at talking about the doomer/optimist stuff in a way thats not-too-tribal and helps people think, it's just very common for it to also affect the way people talk and reason.

Like, it's good IMO that that Paul piece got pretty upvoted, but, the way that many people related to Eliezer and Paul as sort of two monkey chieftains with narratives to rally around, more than just "here are some abstract ideas about what makes alignment hard or easy", is telling. (The evidence for this is subtle enough I'm not going to try to argue it right now, but I think it's a very real thing. My post here today is definitely part of this pattern. I don't know exactly how I could have written it without doing so, but there's something tragic about it)

Please don't awkwardly distance yourself because it didn't end up saying exactly the things you would have said, unless it's actually fucking important.

Raemon, thank for you writing this! I recommend each of us pause and reflect on how we (the rationality community) sometimes have a tendency to undermine our own efforts. See also Why Our Kind Can't Cooperate.

Fwiw, I'm not sure if you meant this, but I don't want to lean too hard on "why our kind can't cooperate" here, or at least not try to use it as a moral cudgel.

I think Eliezer and Nate specifically were not attempting to do a particular kind of cooperation here (with people care about x-risk but disagree with the book's title). They could have made different choices if they wanted to.

I this post I defend their right and reasoning for making some of those choices. But, given that they made them, I don't want to pressure people to cooperate with the media campaign if they don't actually think that's right.

(There's a different claim you may be making which is "look inside yourself and check if you're not-cooperating for reasons you don't actually endorse", which I do think is good, but I think people should do that more out of loyalty to their own integrity than out of cooperation with Eliezer/Nate)

I'm pretty sure that p(doom) is much more load-bearing for this community than policymakers generally. And frankly, I'm like this close to commissioning a poll of US national security officials where we straight up ask "at percent X of total human extinction would you support measures A, B, C, D, etc."

I strongly, strongly, strongly suspect based on general DC pattern recognition that if the US government genuinely belived that the AI companies had a 25% chance of killing us all, FBI agents would rain out of the sky like a hot summer thunderstorm, sudden, brilliant, and devastating.

I... really don't know what Scott expected a story that featured actual superintelligence to look like. I think the authors bent over backwards giving us one of the least-sci-fi stories you could possibly tell that includes superintelligence doing anything at all, without resorting to "superintelligence just won't ever exist."

What about literally the AI 2027 story which does involve superintelligence and Scott thinks doesn't sound "unnecessarily dramatic". I think AI 2027 seems much more intuitively plausible to me and it seems less "sci-fi" in...

What about literally the AI 2027 story which does involve superintelligence and Scott thinks doesn't sound "unnecessarily dramatic". I think AI 2027 seems much more intuitively plausible to me and it seems less "sci-fi" in this sense. (I'm not saying that "less sci-fi" is much evidence it's more likely to be true.)

I think if the AI 2027 had more details, they would look fairly similar to the ones in the Sable story. (I think the Sable story substitutes in more superpersuasion, vs military takeover via bioweapons. I think if you spelled out the details of that, it'd sound approximately as outlandish (less reliant on new tech but triggering more people to say "really? people would buy that?". The stories otherwise seems pretty similar to me.)

>superintelligence

Small detail: My understanding of the IABIED scenario is that their AI was only moderately superhuman, not superintelligent

I think the amount of discontinuity in the story is substantially above the amount of discontinuity in more realistic-seeming-to-me stories like AI 2027 (which is also on the faster side of what I expect, like a top 20% takeoff in terms of speed). I don't think think extrapolating current trends predicts this much of a discontinuity.

I am pretty surprised for you to actually think this.

Here are some individual gears I think. I am pretty curious (genuinely, not just as a gambit) about your professional opinion about these:

- the "smooth"-ish lines we see are made of individual lumpy things. The individual lumps usually aren't that big, the reason you get smooth lines is when lots of little advancements are constantly happening and they turn out to add up to a relatively constant rate.

- "parallel scaling" is a fairly reasonable sort of innovation, it's not necessarily definitely-gonna-happen but it is a) the sort of thing someone might totally try doing and work, after ironing out a bunch of kinks, b) is a reasonable parallel for the invention of chain-of-thought. They could have done something more like an architectural improvement that's more technically opaque (that's more equival

Why do I think the story involves a lot of discontinuity (relative to what I expect)?

- Right at the start of the story, Sable has much higher levels of capability than Galvanic expects. It can confortably prove the Riemann Hypothesis even though Galvanic engineers are impressed by it proving some modest theorems. Generally, it seems like for a company to be impressed by a new AI's capabilities while it's actual capabilities are much higher probably requires a bunch of discontinuity (or requires AIs to ongoingly sandbag more and more each generation).

- There isn't really any discussion of how the world has been changed by AI (beyond Galvanic developing (insufficient) countermeasures based on studying early systems) while Sable is seemingly competitive with top human experts or perhaps superhuman. For instance, it can prove the Riemann hypothesis with only maybe like ~$3 million in spending (assuming each GPU hour is like $2-4). It could be relatively much better at math (which seems totally plausible but not really how the story discusses it), but naively this implies the AI would be very useful for all kinds of stuff. If humans had somewhat weaker systems which were aligned enough t

Section I just added:

...Would it have been better to use a title that fewer people would feel the need to disclaim?

I think Eliezer and Nate are basically correct to believe the overwhelming likelihood if someone built "It" would be everyone dying.

Still, maybe they should have written a book with a title that more people around these parts wouldn't feel the need to disclaim, and that the entire x-risk community could have enthusiastically gotten behind. I think they should have at least considered that. Something more like "If anyone builds it, everyone

I wonder if there’s a disagreement happening about what “it” means.

I think to many readers, the “it” is just (some form of superintelligence), where the question (Will that superintelligence be so much stronger than humanity such that it can disempower humanity?) is still a claim that needs to be argued.

But maybe you take the answer (yes) as implied in how they’re using “it”?

...It" means AI that is actually smart enough to confidently defeat humanity. This can include, "somewhat powerful, but with enough strategic awareness to maneuver into more power witho

more epistemic-prisoner's-dilemma-cooperative-ish strategies

nit: I'd call this maybe 'PR non-unilateralist strategies'. I'm not sure it's structurally much like a prisoner's dilemma, more like a deferral to the in-principle existence of a winner's curse and pricing that into one's media strategy.

roll to disbelieve

(picking on you in particular only because I'm here; complete nit unrelated to (very good) content)

I increasingly hate this phrase. It's such a pointless word-slop shibboleth. Stop it!

I had been considering whether to buy the book, given that I already believe the premise and don't expect reading it to change my behavior. This post (along with other IABED-related discourse) put me over my threshold for thinking the book likely to have a positive effect on public discourse, so I bought ten copies and plan to donate most of them to my public library.

Reasons people should consider doing this themselves:

- Buying more copies will improve the sales numbers, which increases the likelihood that this is talked about in the news, which hopefully sh

Once you do that, it’s a fact of the universe, that the programmers can’t change, that “you’d do better at these goals if you didn’t have to be fully obedient”, and while programmers can install various safeguards, those safeguards are pumping upstream and will have to pump harder and harder as the AI gets more intelligent. And if you want it to make at least as much progress as a decent AI researcher, it needs to be quite smart.

Is there a place where this whole hypothesis about deep laws of intelligence is connected to reality? Like, how hard they have...

Thank you for writing this. Most of what you wrote is almost exactly what I've been thinking when reading discussions about the book. You worded my thoughts so much better than I ever could!

...Do you think there will be at least one company that's actually sufficiently careful as we approach more dangerous levels of AI, with enough organizational awareness to (probably) stop when they get to a run more dangerous than they know how to handle? Cool. I'm skeptical about that too. And this one might lead to disagreement with the book's secondary thesis of "And therefore, Shut It Down," but, it's not (necessarily) a disagreement with "If someone built AI powerful enough to destroy humanity based on AI that is grown in unpredictable ways with similar

Alt title: "I don't believe you that you actually disagree particularly with the core thesis of the book, if you pay attention to what it actually says."

I'm annoyed by various people who seem to be complaining about the book title being "unreasonable". i.e. who don't merely disagree with the title of "If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies", but, think something like: "Eliezer/Nate violated a Group-Epistemic-Norm."

I think the title is reasonable.

I think the title is probably true. I'm less confident than Eliezer/Nate, but I don't think it's unreasonable for them to be confident in it given their epistemic state. So I want to defend several decisions about the book I think were:

I've heard different things from different people and maybe am drawing a cluster where there is none, but, some things I've heard:

Complaint #1: "They really shouldn't have exaggerated the situation like this."

Complaint #2: "Eliezer and Nate are crazy overconfident, and it's going to cost them/us credibility."

Complaint #3: "It sucks that the people with the visible views are going to be more extreme, eye-catching and simplistic. There's a nearby title/thesis I might have agreed with, but it matters a lot not to mislead people about the details."

"Group epistemic norms" includes both how individuals reason, and how they present ideas to a larger group for deliberation.

Complaint #1 emphasizes culpability about dishonesty (by exaggeration). I agree that'd be a big deal. But, this is just really clearly false. Whatever else you think, its pretty clear from loads of consistent writing that Eliezer and Nate do just literally believe the title, and earnestly think it's important.

Complaint #2 emphasizes culpability in terms of "knowingly bad reasoning mistakes." i.e, "Eliezer/Nate made reasoning mistakes that led them to this position, it's pretty obvious that those are reasoning mistakes, and people should be held accountable for major media campaigns based on obvious mistakes like that."

I do think it's sometimes important to criticize people for something like that. But, not this time, because I don't think they made obvious reasoning mistakes.

I have the most sympathy for Complaint #3. I agree there's a memetic bias towards sensationalism in outreach. (Although there are also major biases towards "normalcy" / "we're gonna be okay" / "we don't need to change anything major". One could argue about which bias is stronger, but mostly I think they're both important to model separately).

It does suck if you think something false is propagating. If you think that, seems good to write up what you think is true and argue about it.[1]

If people-more-optimistic-than-me turn out to be right about some things, I'd agree the book and title may have been a mistake.

Also, I totally agree that Eliezer/Nate do have some patterns that are worth complaining about on group epistemic grounds, that aren't the contents of the book. But, that's not a problem with the book.

I think it'd be great for someone who earnestly believes "If anyone builds it, everyone probably dies but it's hard to know" to publicly argue for that instead.

I. Reasons the "Everyone Dies" thesis is reasonable

What the book does and doesn't say

The book says, confidently, that:

The book does not claim confidently that AI will come soon, or shaped any particular way. (It does make some guesses about what is likely, but, those are guesses and the book is pretty clear about the difference in epistemic status).

The book doesn't say you can't build something that's not "It", that is useful in some ways. (It specifically expresses some hope in using narrow biomedical-AI to solve various problems).

The book says if you build it, everyone dies.

"It" means AI that is actually smart enough to confidently defeat humanity. This can include, "somewhat powerful, but with enough strategic awareness to maneuver into more power without getting caught." (Which is particularly easy if people just straightforwardly keep deploying AIs as they scale them up).

The book is slightly unclear about what "based on current techniques" means (which feels like a fair complaint). But, I think it's fairly obvious that they mean the class of AI training that is "grown" more than "crafted" – i.e. any techniques that involve a lot of opaque training, where you can't make at least a decently confident guess about how powerful the next training run will turn out, and how it'll handle various edge cases.

Do you think interpretability could advance to where we can make reasonably confident predictions about what the next generation would do? Cool. (I'm more skeptical it'll happen fast enough, but, it's not a disagreement with the core thesis of the book, since it'd change the "based on anything like today's understanding of AI" clause)[2]

Do you think it's possible to control somewhat-strong-AI with a variety of techniques that make it less likely that it would be able to take over all humanity? I think there is some kind of potential major disagreement somewhere around here (see below), but it's not automatically a disagreement.

Do you think there will be at least one company that's actually sufficiently careful as we approach more dangerous levels of AI, with enough organizational awareness to (probably) stop when they get to a run more dangerous than they know how to handle? Cool. I'm skeptical about that too. And this one might lead to disagreement with the book's secondary thesis of "And therefore, Shut It Down," but, it's not (necessarily) a disagreement with "*If* someone built AI powerful enough to destroy humanity based on AI that is grown in unpredictable ways with similar-to-current understanding of AI, then everyone will die."

The book is making a (relatively) narrow claim.

You might still disagree with that claim. I think there are valid reasons to disagree, or at least assign significantly less confidence to the claim.

But none of the reasons listed so far are disagreements with the thesis. And, remember, if the reason you disagree is because you think our understanding of AI will improve dramatically, or there will be a paradigm shift specifically away from "unpredictably grown" AI, this also isn't actually a disagreement with the sentence.

I think a pretty reasonable variation on the above is "Look, I agree we need more understanding of AI to safely align a superintelligence, and better paradigms. But, I don't expect to agree with Eliezer on the specifics of how much more understanding we need, when we get into the nuts and bolts. And I expect a lot of progress on those fronts by default, which changes my relationship to the secondary thesis of 'and therefore, shut it all down." But, I think it makes more sense to characterize this as "disagree with the main thesis by degree, but not in overall thrust).

I also think a lot of people just don't really believe in AI that is smart enough to outmaneuver all humanity. I think they're wrong. But, if you don't really believe in this, and think the book title is false, I... roll to disbelieve on you actually really simulating the world where there's an AI powerful enough to outmaneuver humanity?

The claims are presented reasonably

A complaint I have about Realtime Conversation Eliezer, or Comment-Thread Eliezer, is that he often talks forcefully, unwilling to change frames, with a tone of "I'm talking to idiots", and visibly not particularly listening to any nuanced arguments anyone is trying to make.

But, I don't have that sort of complaint about this book.

Something I like about the book is it lays out disjunctive arguments, like “we think ultimately, a naively developed superintelligence would want to kill everyone, for reasons A, B, C and D. Maybe you don’t buy reasons B, C and D. But that still leaves you with A, and here’s are argument that although Reason A might not lead literally everyone dying, the expected outcome is still something horrifying.”

(An example of that was: For “might the AI keep us as pets?”, the book answers (paraphrased) “We don’t think so. But, even if they did… note that, while humans keep dogs as pets, we don’t keep wolves as pets. Look at the transform from wolf to dog. An AI might keep us as pets, but, if that’s your hope, imagine the transform from Wolves-to-Dogs and equivalent transforms on humans.”)

Similarly, I like that in the AI Takeoff scenario, there are several instances where it walks through "Here are several different things the AI could try to do next. You might imagine that some of them aren't possible, because the humans are doing X/Y/Z. Okay, let's assume X/Y/Z rule out options 1/2/3. But, that leaves options 4/5/6. Which of them does the AI do? Probably all of them, and then sees which one works best."

Reminder: All possible views of the future are wild.

@Scott Alexander described the AI Takeoff story thus:

I... really don't know what Scott expected a story that featured actual superintelligence to look like. I think the authors bent over backwards giving us one of the least-sci-fi stories you could possibly tell that includes superintelligence doing anything at all, without resorting to "superintelligence just won't ever exist."

Eliezer and Nate make sure the takeover scenario doesn't depend on technologies that we don't have some existing examples of. The amount of "fast takeoff" seems like the amount of scaleup you'd expect if the graphs just kept going up the way they're currently going up, by approximately the same mechanisms they currently go up (i.e. some algorithmic improvements, some scaling).

Sure, Galvanic would first run Sable on smaller amounts of compute. And... then they will run it on larger amounts of compute (and as I understand it, it'd be a new, surprising fact if they limited themselves to scaling up slowly/linearly rather than by a noticeable multiplier or order-of-magnitude. If I am wrong about current lab practices here, please link me some evidence).

If this story feels crazy to you, I want to remind you that all possible views of the future are wild. Either some exponential graphs suddenly stop for unclear reasons, or some exponential graphs keep going and batshit crazy stuff can happen that your intuitions are not prepared for. You can believe option A if you want, but, it's not like "the exponential graphs that have been consistent over hundreds of years suddenly stop" is a viewpoint that you can safely point to as a "moderate" and claim to give the other guy burden of proof.

You don't have the luxury of being the sort of moderate who doesn't have to believe something pretty crazy sounding here, one way or another.

(If you haven't yet read the Holden post on Wildness, I ask you do so before arguing with this. It's pretty short and also fun to read fwiw)

The Online Resources spell out the epistemic status more clearly.

In the FAQ question, "So there's at least a chance of the AI keeping us alive?", they state more explicitly:

The book doesn't actually overextend the arguments and common discourse norms.

This adds up to seeming to me that:

If a book in the 50s was called "Nuclear War would kill us all", I think that book would have been incorrect (based of my most recent read of Nuclear war is unlikely to cause human extinction), but I wouldn't think the authors were unreasonable for arguing it, especially if they pointed out things like "and yeah, if our models of nuclear winter are wrong, everyone wouldn't literally die, but civilization would still be pretty fucked", and I would think the people giving the authors a hard time about it were being obnoxious pedants, not heroes of epistemic virtue.

(I would think people arguing "but, the nuclear winter models are wrong, so, yeah, we're more in the 'civilization would be fucked' world than the 'everyone literally dies world." would be doing a good valuable service. But I wouldn't think it'd really change the takeaways very much).

II. Specific points to maybe disagree on

There are some opinions that seem like plausible opinions to hold, given humanity's current level of knowledge, that lead to actual disagreement with "If anyone builds [an AI smart enough to outmanuever humanity] [that is grown in unpredictable ways] [based on approximately our current understanding of AI]".

And the book does have a secondary thesis of "And therefore, Shut It Down", and you can disagree with that separately from "If anyone builds it, everyone dies."

Right now, the arguments that I've heard sophisticated enough versions of to seem worth acknowledging include:

I disagree with the first two being very meaningful (as counterarguments to the book). More on that in a sec.

Argument #3 is somewhat interesting, but, given that it'd take years to get a successful Global Moratorium, I don't see any reason not to start pushing for a long global pause now.

I think the fourth one is fairly interesting. While I strongly disagree with some major assumptions in the Redwood Plan as I understand it, various flavors of "leverage narrow / medium-strength controlled AIs to buy time" feel like they might be an important piece of the gameboard. Insofar as Argument #3 helped Buck step outside the MIRI frame and invent Control, and insofar as that helps buy time, yep, seems important.

This is complicated by "there is a giant Cope Memeplex that really doesn't want to have to slow down or worry too much", so while I agree it's good to be able to step outside the Yudkowsky frame, I think most people doing it are way more likely to end up slipping out of reality and believing nonsense than getting anywhere helpful.

I won't get into that much detail about either topic, since that'd pretty much be a post to itself. But, I'll link to some of the IABED Online Resources, and share some quick notes about why I disagree that even the sophisticated versions of these so far don't seem very useful arguments to me.

On the meta-level: It currently feels plausible to me to have some interesting disagreements with the book here, but I don't see any interesting disagreements that add up to "Eliezer/Nate particularly fucked up epistemically or communicatively" or "you shouldn't basically hope the book succeeds at its goal."

Notes on Niceness

There are some flavors of "AI might be slightly nice" that are interesting. But, they don't seem like it changes any of our decisions. It just makes us a bit more hopeful about the end result.

Given the counteraguments, I don't see a reason to think this more than single-digit-percent likely to be especially relevant. (I can see >9% likelihood the AIs are "nice enough that something interesting-ish happens" but not >9% likelihood that we shouldn't think the outcome is still extremely bad. The people who think otherwise seem extremely motivatedly-cope-y to me).

Note also that it's very expensive for the AI to not boil the oceans / etc as fast as possible, since that means losing a many galaxies worth of resources, so it seems like it's not enough to be "very slightly" nice – it has to be, like, pretty actively nice.

Which plan is Least Impossible?

A lot of x-risk disagreements boil down to "which pretty impossible-seeming thing is only actually Very Hard instead of Impossibly Hard."

There's an argument I haven't heard a sophisticated version of, which is "there's no way you're getting a Global Pause."

I certainly believe that this is an extremely difficult goal, and a lot of major things would need to change in order for it to happen. I haven't heard any real argument we should think it's more impossible than, say, Trump winning the presidency and going on to do various Trumpy things.

(Please don't get into arguing about Trump in the comments. I'm hoping that whatever you think of Trump, you agree he's doing a bunch of stuff most people would previously have probably expected to be outside the overton window. If this turns out to be an important substantive disagreement I'll make a separate container post for it)

Meanwhile, the counter-impossible-thing I've heard several people putting hope on is "We can run a lot of controlled AIs, where (first) we have them do fairly straightforward automation of not-that-complex empirical work, which helps us get to a point where we trust them enough to give them more openended research tasks."

Then, we run a lot of those real fast, such that they substantial increase the total amount of alignment-research-months happening during a not-very-long-slowdown.

The arguments for why this is extremely dangerous, from the book and online resources and maybe some past writing, are, recapped:

There's no good training data.

We don't even know how to verify alignment work is particular useful among humans, let alone in an automatedly gradable way.

Goal Directedness is pernicious. Corrigibility is anti-natural.

The way an AI would develop the ability to think extended, useful creative research thoughts that you might fully outsource to, is via becoming perniciously goal directed. You can't do months or years of openended research without fractally noticing subproblems, figuring out new goals, and relentless finding new approaches to tackle them.

Once you do that, it's a fact of the universe, that the programmers can't change, that "you'd do better at these goals if you didn't have to be fully obedient", and while programmers can install various safeguards, those safeguards are pumping upstream and will have to pump harder and harder as the AI gets more intelligent. And if you want it to make at least as much progress as a decent AI researcher, it needs to be quite smart.

Security is very difficult

The surface area of ways an AI can escape and maneuver are enormous. (I think it's plausible to have a smallish number of carefully controlled, semi-powerful AIs if you are paying a lot of attention. The place I completely get off the train is where you then try to get lots of subjective hours of research time out of thousands of models).

Alignment is among the most dangerous tasks

"Thinking about how to align AIs" requires both for the AI to think how "how would I make smarter version of myself" and "how would I make it aligned to humans?". The former skillset directly helps them recursively self-improve. The latter skillset helps them manipulate humans.

MIRI did make a pretty substantive try.

One of the more useful lines for me, in the Online Resources, in their extended discussions about corrigibility.

There was a related quote I can't find now, that maybe was just in an earlier draft of the Online Resources, to the effect of "this [our process of attempting to solve corrigibility] is the real reason we have this much confidence about this being quite hard and our current understanding not being anywhere near adequate."

(Fwiw I think it is a mistake that this isn't at least briefly mentioned in the book. The actual details would go over most people's heads, but, having any kind of pointer to "why are these guys so damn confident?" seems like it'd be quite useful)

III. Overton Smashing, and Hope

Or: "Why is this book really important, not just 'reasonable?'"

I, personally, believe in this book. [3]

If you don't already believe in it, you're probably not going to because of my intuitions here. But, I want to say why it's deeply important to me that the book is reasonable, not just arguing on the internet because I'm triggered and annoyed about some stuff.

I believe in the book partly because it looks like it might work.

The number (and hit-rate) of NatSec endorsements surprised me. More recently some senators seem to have been bringing up existential risk of their own initiative. When I showed the website to a (non-rationalist) friend who lives near DC and has previously worked for think-tank-ish org, I expected them to have a knee-jerk reaction of ‘man that’s weird and a bit cringe’, or ‘I’d be somewhat embarrassed to share this website with colleagues’, and instead they just looked worried and said “okay, I’m worried”, and we had a fairly matter-of-fact conversation about it.

It feels like the world is waking up to AI, and is aware that it is some kind of big deal that they don’t understand, and that there’s something unsettling about it.

I think the world is ready for this book.

I also believe in the book because, honestly, the entire rest of the AI safety community’s output just does not feel adequate to me to the task of ensuring AI goes well.

I’m personally only like 60% on “if anyone built It, everyone would die.” But I’m like 80% on “if anyone built It, the results would be unrecoverably catastrophic,” and the remaining 20% is a mix of model uncertainty and luck. Nobody has produced counterarguments that feel compelling, just "maybe something else will happen?", and the way people choose their words almost always suggests some kind of confusion or cope.

The plans that people propose mostly do not seem to be counter-arguing the actual difficult parts of the problem.

The book gives me more hope than anything else has in the past few years.

Overton Smashing is a thing. I really want at least some people trying.

It’s easy to have the idea “try to change the Overton window.” Unfortunately, changing the Overton window is very difficult. It would be hard for most people to pull it off. I think it helps to have a mix of conviction backed by deep models, and some existing notoriety. There are only a few other people who seem to me like they might be able to pull it off. (It'd be cool if at least one of Bengio, Hinton, Hassabis or Amodei end up trying. I think Buck actually might do a good job if he tried.)

Smashing an overton window does not look like "say the careful measured thing, but, a bit louder/stronger." Trying to do it halfway won't work. But going all in with conviction and style, seems like it does work. It looks like Bengio, Hinton, Hassabis and Amodei are each trying to do some kind of measured/careful strategy, and it's salient that if they shifted a bit, things would get worse instead of better.

(Sigh... I think I might need to talk about Trump again. This time it seems more centrally relevant to talk about in the comments. But, like, dude, look at how bulletproof the guy seems to be. He also, like, says falsehoods a lot and I'm not suggesting emulating him-in-particular, but I point to him as an existence proof of what can work)

People keep asking "why can't Eliezer tone it down." I don't think Eliezer is the best possible spokesperson. I acknowledge some downside risk to him going on a major media campaign. But I think people are very confused about how loadbearing the things some people find irritating are. How many fields and subcultures have you founded, man? Fields and subcultures and major new political directions are not founded (generally) by people without some significant fraction of haters.

You can't file off all the edges, and still have anything left that works. You can only reroll on which combination of inspiring and irritating things you're working with.

I want there to be more people who competently execute on "overton smash." The next successful person would probably look pretty different from Eliezer, because part of overton smashing is having a unique style backed by deep models and taste and each person's taste/style/models are pretty unique. It'd be great to have people with more diversity of "ways they are inspiring and also grating."

Meanwhile, we have this book. It's the Yudkowsky version of the book. If you don't like that, find someone who actually could write a better one. (Or, rather, find someone who could execute on a successful overton smashing strategy, which would probably look pretty different than a book since there already is a book, but would still look and feel pretty extreme in some way).

Would it have been better to use a title that fewer people would feel the need to disclaim?

I think Eliezer and Nate are basically correct to believe the overwhelming likelihood if someone built "It" would be everyone dying.

Still, maybe they should have written a book with a title that more people around these parts wouldn't feel the need to disclaim, and that the entire x-risk community could have enthusiastically gotten behind. I think they should have at least considered that. Something more like "If anyone builds it, everyone loses." (that title doesn't quite work, but, you know, something like that)

My own answer is "maybe" - I see the upside. I want to note some of the downsides or counter-considerations.

(Note: I'm specifically considering this from within the epistemic state of "if you did pretty confidently believe everyone would literally die, and that if they didn't literally die, the thing that happened instead would be catastrophically bad for most people's values and astronomically bad from Eliezer/Nate's values)

Counter-considerations include:

AFAICT, Eliezer and Nate spent like ~8 years deliberately backing off and toning tone, out of a vague deferral to people saying "guys you suck at PR and being the public faces of this movement." The result of this was (from their perspective) "EA gets co-opted by OpenAI, which launches a race that dramatically increases the danger the world faces."

So, the background context here is that they have tried more epistemic-prisoner's-dilemma-cooperative-ish strategies, and they haven't worked well.

Also, it seems like there's a large industrial complex of people arguing for various flavors of "things are pretty safe", and there's barely anyone at all stating plainly "IABED". MIRI's overall strategy right now is to speak plainly about what they believe, both because they think it needs to be said and no one else is saying it, and because they hope just straightforwardly saying what they believe will net a reputation for candor that you don't get if people get a whiff of you trying to modulate your beliefs based on public perception.

None of that is an argument that they should exaggerate or lean-extra-into beliefs that they don't endorse. But, given that they are confident about it, it's an argument not to go out of their way to try to say something else.

I don't currently buy that it costs much to have this book asking for total shutdown.

My sense is it's pretty common for political groups to have an extreme wing and a less extreme wing, and for them to be synergistic. Good cop, bad cop. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X.

If what you want is some kind of global coordination that isn't a total shutdown, I think it's still probably better to have Yudkowsky over there saying "shut it all down" and say "Well, I dunno about that guy. I don't think we need to shut it all down, but I do think we want some serious coordination."

I believe in the book.

Please buy a copy if you haven't yet.

Please tell your friends about it.

And, disagree where appropriate, but, please don't give it a hard time for lame pedantic reasons, or jump to assuming you disagree because you don't like something about the vibe.

Please don't awkwardly distance yourself because it didn't end up saying exactly the things you would have said, unless it's actually fucking important.(I endorse something close to this but the nuances matter a lot and I wrote this at 5am and don't stand by it enough for it to be the closing sentence of this post)You can buy the book here.

(edit in response to Rohin's comment: It additionally sucks that writing up what's true and arguing for it is penalized in the game against sensationalism. I don't think it's so penalized it's not worth doing, though)

Paul Christiano and Buck both complain about (paraphrased) "Eliezer equivocates between 'we have to get it right on the first critical try' and 'we can't learn anything important before the first critical try.'"

I agree something-in-this-space feels like a fair complaint, especially in combination with Eliezer not engaging that much with the more thoughtful critics, and tending to talk down to them in a way that doesn't seem to be really listening to the nuances they're trying to point to and round them to nearest strawman of themselves. I

I think this is a super valid thing to complain about Eliezer. But, it's not the title or thesis of the book. (because, if we survive because we learned useful things, I'd say that doesn't count as "anywhere near our current understanding").

"Believing in" doesn't mean "assign >50% chance to working", it means "assign enough chance (~20%?) that it feels worth investing substantially in and coordinating around." See Believing In by Anna Salamon.