Does this include an analysis of alcohol's benefits beyond the general acknowledgment in the conclusion? I think they are subtle but powerful. Alcohol is often used as a social-bonding and truth-telling influence. Like caffeine, it doesn't give more of anything in the long term, but allows users some conscious control over distribution of their moods and energy. And it can shift moods out-of-distribution temporarily toward joy (as well as anger), with potential long-lasting beneficial effects, as the uathor mentions.

I'm not making an argument that alcohol should remain a part of society, just pointing out that the positive factors need to be carefully considered before making a broad and strong recommendation like this.

I just skiimmed because I need to stay focused on work, and I'm aware that alcohol has a staggering list of harms.

In the "benefits" section probably goes an increased birth rate. I would guess that alcohol begins more lives than it ends.

Some of the scenarios I was thinking about included people who started dating due to alcohol, and then later have an intended pregnancy.

But also, it does depend on whether we are looking at the local "do these people want to be pregnant" or the societal "what would a drop in birthrate do to society".

If someone offered to sell you these positive experiences, how much would be too much to pay?

How much would these experiences need to be worth for them to collectively outweigh the harm?

Given the violence, shortened or ended lives, diminished quality of some lives, it seems like one of these numbers, even with a rough lower bound, is much bigger than the other for me, such that careful consideration is not necessary.

Then again, maybe I should work on increasing that upper bound :D

That's not the option though; if I stop drinking it will barely affect others' drinking.

If it were my choice, I'd still consider carefully. Alcohol causes a whole lot of fun and random enthusiasm!

I'd be very cautious of shutting to a less fun, more staid society.

I'd want to focus on changing things to reduce harms in other ways, or making sure there were replacements for those sources of fun and funding and random enthusiasm.

Civilization evolved with beer, wine, and mead, but we've only recently had liquor. (Roughly, minimum 7000 years of beer, 700 years of liquor). One observation I am very confident of is that my college's underage alcohol policies drove people to liquor because it was easier to conceal, and this went very poorly for a number of my friends, while the students who started with beer before college generally did alright. I have some suspicion that this is representative, and a large fraction of the damage we see from alcohol is distillation specific. I also suspect that this generalizes- for example, we handled fruits and seeds for millions of years and are getting wrecked by high fructose corn syrup and canola oil, listening to song and stories around the campfire is good for you and tiktok isn't, etc.

60% of alcohol is sold to the top 10% of drinkers, who drink an average of 74 drinks per week. [...] When you pay for alcohol, you’re paying a business that is being significantly funded by addicts of the substance it’s selling. You’re helping it stay in business and grow.

Some thoughts:

- If all non-alcoholics quit drinking, then alcohol demand would drop by 40%, which doesn't seem that much. I expect that this would increase the price of alcohol by an imperceptible amount in the long-term, and decrease the price of alcohol in the short-term.[1]

- If you consider the alcohol industry as a single business, then most of its revenue comes from alcoholics. But the alcohol industry isn't a single business! If I buy a bottle of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, I doubt there exists any business in the supply chain of the bottle which relies on alcoholics for the majority of their revenue.[2]

I stopped drinking ~9 years ago. It's nice to think I'm not benefiting only myself, but society as well! BTW, if anyone else wants to quit, Allen Carr's Easy Way to Control Alcohol really did make it easy!

When you step into a liquor store, the majority of the alcohol you see will likely be sold to people whose health it’s significantly harming

This does not follow and is probably not true. Heavy drinkers tend to consume low-profit cheap forms, often highly concentrated. Most of visible inventory is advertising diversity and trying to get moderate drinkers to buy something more expensive.

I'm not sure how relevant this is to the rest of the argument, but I see people assert that this is true and relevant all the time and I must rebut.

I drink a lot less than I did in my youth, and would only be mildly inconvenienced if I never drank again. But it's not fully cost-free - I do enjoy a few drinks on occasion, as do many people I like to hang out with. Also, have all the "a few drinks a week seems to reduce all-cause mortality" studies been fully debunked?

I will not be joining you in your temperance campaign, nor do I support significant restrictions on availability of such choices for most adults. I would enjoy seeing greater penalties for public inebriation, and additional penalties for crimes committed while inebriated. But I see no simple, acceptable interventions that makes abuse much harder while keeping harmless/beneficial uses available to most.

Note - I feel similarly, but more strongly about marijuana. I'm glad it's legal in many/most places, and I don't support returning to prohibition, but I hate the smell and the social acceptability of it that makes it so much more prevalent than I prefer.

Out of curiosity, do you think of this topic in terms of mistake or conflict theory? Do heavy users and those causing harm just not know or are somehow unable to make better choices, or are they intentionally and selfishly taking risks (and imposing them on others)? These lead to very different interventions.

I think we need to take seriously the fact that civilization evolved with alcohol. I'm not saying alcohol is load bearing to civilization, but what I am saying is that there's a strong Chesterton's Fence argument to be made against teetotaling, and time we tried it in America it failed spectacularly, not just because people wanted to keep drinking, but because it failed to get people to stop drinking and resulted in a lot of bad secondary effects, like normalizing organized crime.

So I think any compelling argument for giving up alcohol when it's not a problem for someone has to adequately understand why alcohol is so popular beyond addiction for the many people who enjoy it and aren't addicted.

The way you apply "Chesterton's Fence" is bordering a fully general argument against any change. This is not how it's supposed to be used. Chesterton's Fence is an argument against getting rid of things, without having knowledge why they existed in the first place. We do have a good model why alcohol consumption coincided with civilization. Therefore, there is no strong argument of this form that can be made here.

You also seem to confuse voluntary teetotaling with government enforced prohibition. All the bad secondary effects are results of the latter, not the former.

I read this post as making a motte and bailey style argument. Perhaps it's just how I'm interpreting the author's somewhat (to me!) vague words, but for example the final sentence:

I understand that for many people giving it up would be more of a sacrifice, but it seems clear that the sacrifice is worth it to protect the people alcohol would otherwise kill and harm.

I interpret the second half to be saying that "the sacrifice" of giving up alcohol is a general statement that applies to everyone, and the author is making a bid here that everyone should make that sacrifice, at which point this is not really voluntary.

Maybe the author meant to say something more precise like "I think more people should voluntarily stop drinking" and some of their post implies this is what they mean, but then other parts seem to me to be written in favor of prohibition. I'm not sure.

Also, I'm far less confident than you that we actually understand the function of alcohol in society, even if we are familiar with its history.

This is an argument against total prohibition. I don't see an argument against making alcohol 20% more expensive or 20% harder to buy.

Sure, but the argument of the post is "alcohol bad for other people so stop drinking", not "alcohol bad for other people so drink marginally less or make drinking marginally harder".

The argument is to change your personal behaviour in order to modify the global multiagent equilibrium at least to some degree.

Well, highly taxed things can lead to a black market to bypass the tax (I think this happens with cigarettes already), and I'm sure if the tax went sufficiently high we would see a rise in moonshine production, organized crime would get back into it, etc.

But I could also interpret this post to be primarily advocating for individuals to develop voluntary social practices of avoiding alcohol. That seems the better option.

It's slightly disappointing and amusing whenever I have to admit my Mormon upbringing was correct about something.

While acknowledging the many harms alcohol does, I hope we can find alternatives that fill the niche of social lubricant with fewer side effects & less abuse potential.

Looking at the crippling social anxiety rampant among those near my age (28) and younger, we need all the help we can get.

In that vein :p, from what I've read nitrous oxide is both completely legal and almost completely harmless as long as it's mixed with oxygen so you don't suffocate (and if used frequently make sure you don't become deficient in vitamin B12).

I'm not sure if/how much it helps with social things as my last experience with it was a dental procedure when I was a kid.

This reminds me of the Mark Twain quip about censorship, but reframed as "Babies can't chew steak, so you should probably stop eating it." I find this argument so repugnant that I take precisely the opposite moral, and now see it as a ethical imperative to preserve this more permissive culture as a way to forestall state coercion.

Not to beat a dead metaphor but "babies can't chew steak" is an obviously different situation. Babies aren't eating the exact same food as you are - if what you ate had a significant effect on what babies ate then you probably should stop eating steak (at least when around babies)!

Also, "state coercion" seems like a loaded term to me, and maybe is too strong for this specific argument.

I don't like the idea of banning things outright either. Prohibition doesn't work, and a state enforcing "you CANNOT have alcohol" would be overreach.

But I do think that barriers between normal people and harmful things should exist - and if people still manage to inflict significant harm on themselves and others, then maybe the barriers should be made taller.

Alcohol has a measurable death toll - and it doesn't just harm the user. It may be worth to take measures against that - by de-normalizing drinking, taxing alcohol more heavily, preventing alcohol from being sold in grocery stores, etc.

Thank you for posting this. I have also been suspicious of whether we should keep this cultural norm. Pretty much everybody underestimates the harm from alcohol.

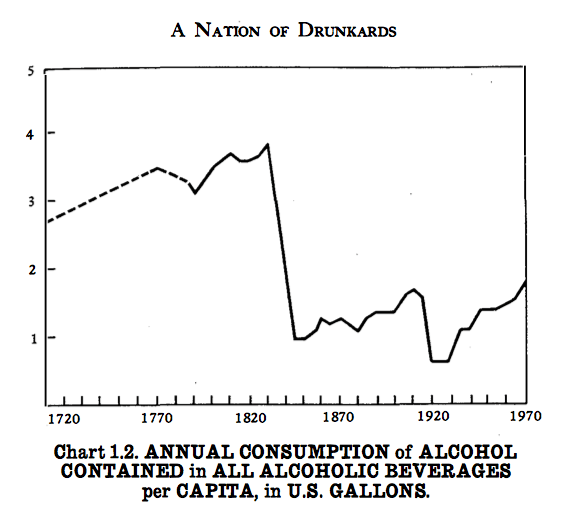

The interesting thing is that we're not the first people to question this. Throughout the entire western world, there was a movement in the early 20th century that saw alcohol clearly: the prohibition movement. It was a global movement, spanning not just the US but also in Canada and the Nordic countries. In the latter it was so successful that the Nordics retain strict controls on alcohol.

By many lights, prohibition was successful: alcohol consumption did decrease during the period (Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History: An International Encyclopedia [2 ... - Jack S. Blocker - Google Books) and rates of liver cirrhosis, alcohol psychosis, and infant mortality declined (Did Prohibition Really Work? Alcohol Prohibition as a Public Health Innovation - PMC). But because the government was unable to control the crime syndicates that profited from selling illegal liquor, prohibition was retroactively deemed a failure. Now nobody is allowed to question the cultural norm of alcohol, because "we tried that already."

But because the government was unable to control the crime syndicates that profited from selling illegal liquor, prohibition was retroactively deemed a failure.

The crime syndicates were the failure.

It's important to mention that alcohol is a known (Group 1) carcinogen. Add another 20,000 cancer related deaths and 100,000 cancer cases per year caused by alcohol to the negative side.

I think this is a good plea since it will be very difficult to coordinate a reduction of alcohol consumption at a societal level. Alcohol is a significant part of most societies and cultures, and it will be hard to remove. Change is easier on an individual level.

I stopped drinking on October 1, 2022, but it required a lot of effort in reprogramming myself to feel comfortable in social settings (Because what Seth's comment said is correct: alcohol is very useful for social bonding). It helps a lot that my spouse seldom drinks and when she does, it is very little.

There are some comments arguing that alcohol should not be banned by the government, or should remain part of society, but this article is about individual choice, not bans. Our World In Data has a good map of lifelong abstinence rate among people 15+, and the proportion ranges from 99% (Kuwait) to 4% (Luxembourg). This shows that civilization can survive and prosper with many teetotalers and with few. There is no Chesterton's Fence here, nothing would break if this article somehow convinced a billion people to stop drinking alcohol (it won't).

I don't often see this behavior on LessWrong. Don't Eat Honey commenters didn't explain that a government ban on honey would normalize organized crime (it would). Maybe because of the discussion of the South African ban as a natural experiment. Perhaps because of the mention of masking and social distancing during the COVID pandemic, which were both subject to government enforcement in many places. Could be politics is the mind-killer. The article would benefit from a disclaimer that it's not advocating for government enforcement, given this misunderstanding.

This is a cross post written by Andy Masley, not me. I found it really interesting and wanted to see what EAs/rationalists thought of his arguments.

This post was inspired by similar posts by Tyler Cowen and Fergus McCullough. My argument is that while most drinkers are unlikely to be harmed by alcohol, alcohol is drastically harming so many people that we should denormalize alcohol and avoid funding the alcohol industry, and the best way to do that is to stop drinking.

This post is not meant to be an objective cost-benefit analysis of alcohol. I may be missing hard-to-measure benefits of alcohol for individuals and societies. My goal here is to highlight specific blindspots a lot of people have to the negative impacts of alcohol, which personally convinced me to stop drinking, but I do not want to imply that this is a fully objective analysis. It seems very hard to create a true cost-benefit analysis, so we each have to make decisions about alcohol given limited information.

I’ve never had problems with alcohol. It’s been a fun part of my life and my friends’ lives. I never expected to stop drinking or to write this post. Before I read more about it, I thought of alcohol like junk food: something fun that does not harm most people, but that a few people are moderately harmed by. I thought of alcoholism, like overeating junk food, as a problem of personal responsibility: it’s the addict’s job (along with their friends, family, and doctors) to fix it, rather than the job of everyday consumers. Now I think of alcohol more like tobacco: many people use it without harming themselves, but so many people are being drastically harmed by it (especially and disproportionately the most vulnerable people in society) that everyone has a responsibility to denormalize it.

You are not likely to be harmed by alcohol. The average drinker probably suffers few if any negative effects. My argument is about how our collective decision to drink affects other people. This post is not about what will happen to you if you continue to drink. It’s about what will happen to vulnerable people if you and I and others continue to drink.

Alcohol is a much bigger problem than you may think

The global disease burden is the most comprehensive single measurement of the total death and disability caused by disease. COVID caused 3.7% of the global disease burden in the first year of the pandemic before vaccines became widely available. In comparison, every year alcohol is responsible for 5.1% of the global disease burden. Alcohol is responsible for 1 in every 20 deaths worldwide each year, which is the same fraction as COVID.

Between 100,000 and 140,000 Americans die each year due to alcohol, which is 2–3 times as many people as are killed by guns in America each year. Drunk driving causes 290,000 injuries per year in the U.S. and costs society $132 billion per year, or $400 per year per person in the country.

Alcohol probably makes people more violent. 30–40% of men who commit intimate partner violence were drinking at the time. 37% of sexual assaults, 27% of aggravated assaults, and 25% of simple assaults occur when the perpetrator is drinking. Half the people in American prisons had alcohol in their system when they committed the crime they were convicted for.

From Alice Evans:

There may be more complex reasons why alcohol is correlated with violence, and it may be that reducing alcohol consumption wouldn’t have much impact on violent crime. However, if limiting alcohol consumption could lower these statistics by even a few percentage points, tens of thousands of Americans would be spared from horrific violence each year. There are some natural experiments on the effects of mass reductions in alcohol consumption. South Africa imposed a sudden and unexpected ban on alcohol in 2020 and injury-induced death fell by 14% and violent crime dropped sharply. This 2018 article on alcohol taxes summarizes the research on alcohol and crime:

Outside of the huge economic costs imposed by death, worse health, and violence related to alcohol, hangovers alone lead to $220 billion in lost productivity each year in the U.S., or $650 for every person in the country per year. Adding this number to the costs of drunk driving alone means that alcohol externalities are costing society over $1000 per year per person. Each person you know is effectively paying $1000 per year for alcohol to be a normal part of our culture, over and above the actual cost of drinks.

Alcoholism is really really really bad. It often (though not always) makes life hell for the people experiencing it and the people who depend on and care about them. Heavy drinkers who are not alcoholics still face shortened lives, serious harm to cognitive ability, and worse physical and mental health. While most drinkers do not become alcoholics, more do than you may expect. 1 in 8 drinkers are heavy drinkers, and 1 in 10 of those heavy drinkers become alcoholics. So at a minimum 1 in 80 people who drink will become an alcoholic. According to the DSM-5’s criteria, 1 in 10 drinkers have either moderate or severe alcohol use disorders.

Why you should stop drinking even if alcohol will not harm you personally

Because alcohol is killing the same number of people as COVID each year, I think we should treat it as a similar emergency. A difference is that many (though not all) deaths due to alcohol were caused by someone who chose to begin drinking, while each COVID victim did not choose to get COVID. I think that there is a moral difference between the two, but not so much that we should “live and let live” and accept the number of alcohol deaths. In this section, I’ll give some arguments for why we have an ethical obligation to denormalize alcohol rather than taking a live and let live attitude to other people drinking.

Most of the time, people behave in patterns they learned from the culture around them. Almost all of my behavior and what I consider normal was learned and copied from the example people around me set. It is very hard to step back from your social context and modify your behavior. In some sense, each individual drinker is choosing to drink, but in another sense, they are each doing what we all do most of the time: following the example of the culture around them. There have been some studies on how much of an effect the general social environment of drinking has on people, and it seems to be quite a lot. This study suggests that the social example of other people accounts for a sizable amount of each drinker’s alcohol consumption:

We can compare the normalization of alcohol to the normalization of other behaviors. During the pandemic, part of the reason I was wearing a mask and socially distancing was to set an example for other people. If I lived in an area where no one was wearing a mask or distancing, it would have felt more difficult to choose to wear a mask and distance. Even though each person was individually choosing to mask and distance, our collective choices had a strong effect. We understood that we had a responsibility to normalize a specific behavior to keep everyone safe, even though each person was ultimately responsible for their own actions. I argue that we have the same responsibility with alcohol.

We can think of ideas and behaviors as spreadable in the same way diseases are spreadable. Before vaccines, we understood that we each had a responsibility to be extremely careful about not spreading COVID, to the point of going months without meeting people indoors. The idea that “it is normal and good to consume alcohol” is harming more people each year than COVID did, and it takes much less of a sacrifice to avoid spreading the idea than it takes to avoid spreading COVID.

I don’t think it is much worse to be murdered than it is to die of a harmful highly addictive personal habit. You are a victim of outside forces in both cases. The fact that alcoholics are mainly harming themselves rather than being harmed by other people bears little moral weight for me. In both cases, they deserve a culture that protects them. Denormalizing drinking is one way we can protect them.

1 person dies from alcohol each year for every 1900 people who drink. This means that throughout a lifetime of drinking (let’s say from 20 to 70) 1 person dies from alcohol for every 38 people who regularly drink. We can think of the 38 people as each casting a vote to normalize alcohol and fund the alcohol industry. Because it takes so few votes for an additional person to die, I do not want to be part of that 38.

60% of alcohol is sold to the top 10% of drinkers, who drink an average of 74 drinks per week. This number is misleading and skewed by the top 1% of drinkers, who drink much more than the top 10%, but the fact remains that the majority of drinks are sold to the tiny minority who consume them the most. When you step into a liquor store, the majority of the alcohol you see will likely be sold to people whose health it’s significantly harming, some of whom are addicted to it. When you pay for alcohol, you’re paying a business that is being significantly funded by addicts of the substance it’s selling. You’re helping it stay in business and grow.

I have a special responsibility as someone who is not genetically predisposed to alcoholism to avoid normalizing behaviors that would ruin the lives of people who are not as lucky, in the same way, that we have a responsibility to donate resources to people who were not given as many opportunities as we were.

In elite culture (which in many ways I consider myself a member of) there are sometimes disturbing status rituals where you engage in more dangerous behavior to demonstrate that you’re strong and rich and able to bounce back. There’s pressure to do more intense drugs and to drink more heavily. It’s hard not to see this as a way of filtering out people perceived as unfit or weak. While most people I know do not participate in this, I have been in social spaces where these rituals happen. They’re a form of social Darwinism and I don’t want anything to do with them. Concern about alcoholism is sometimes seen as an implicit weakness, and more people not drinking and raising concern about alcoholism can make it socially easier for even more people to avoid alcohol.

Alcohol is so normalized that most people have no reaction to negative statistics about it. It’s culturally understood that alcohol causes problems, so it’s easier to ignore how harmful it is. If alcohol were anything else and had the same negative consequences, it would be clear that we should not participate in it. If Minecraft were killing 140,000 Americans every year, and if 40% of intimate partner violence occurred after the perpetrator was playing Minecraft, I would not buy or play it. Like alcohol, Minecraft is very fun, but it would not be worth it for me even if I knew it would never personally harm me, because it was having so many negative effects on other people. I would not want to financially support it or normalize playing it.

I can’t think of another activity that’s both as dangerous as alcohol and as normalized. Smoking is more dangerous but much more frowned upon. Driving is more normalized but less dangerous.

Because so many people are being harmed by alcohol, even very small changes in drinking habits can lead to lots of lives being saved. This 2015 study suggests that an alcohol tax that raises the price of alcohol by 10% would save between 2000–6000 American lives per year. If a six-pack of Bud Light costing $0.50 more would save the same number of Americans every year as the number who died on 9/11, it seems clear that individuals setting an example for their peers can also have an outsized influence on the number of people harmed.

It will always be unclear how much effect the example we set can have, but I think it’s higher than we assume. We are highly influenced by the lifestyles of the people we’re closest with. If the 5 closest people in your life were heavy drinkers, you would probably have a very different relationship with alcohol than if your 5 closest people did not drink. Change in behavior of one person in a social group can have unexpected effects, especially if that person is well-respected and clear about why they decided to not drink.

Conclusion

In the past, I’ve been greatly benefited by alcohol. Being drunk sometimes left me so happy that I lingered in a more positive emotional state for weeks after. I take the social benefits of alcohol seriously, but I don’t think they’re worth the cost of so many vulnerable people being harmed and killed, and life without alcohol is just as exciting and fun for me. I understand that for many people giving it up would be more of a sacrifice, but it seems clear that the sacrifice is worth it to protect the people alcohol would otherwise kill and harm.