Hi! Clara here. Thanks for the response. I don't have time to address every point here, but I wanted to respond to a couple of the main arguments (and one extremely minor one).

First, FOOM. This is definitely a place I could and should have been more careful about my language. I had a number of drafts that were trying to make finer distinctions between FOOM, an intelligence explosion, fast takeoff, radical discontinuity, etc. and went with the most extreme formulation, which I now agree is not accurate. The version of this argument that I stand by is that the core premise of IABIED does require a pretty radical discontinuity between the first AGI and previous systems for the scenario it lays out to make any sense. I think Nate and Eliezer believe they have told a story where this discontinuity isn't necessary for ASI to be dangerous – I just disagree with them! Their fictional scenario features an AI that quite literally wakes up overnight with the completely novel ability and desire to exfiltrate itself and execute a plan allowing it to take over the world in a manner of months. They spend a lot of time talking about analogies to other technical problems which are hard because we're forced to go into them blind. Their arguments for why current alignment techniques will necessarily fail rely on those techniques being uninformative about future ASIs.

And I do want to emphasize that I think their argument is flawed because it talks about why current techniques will necessarily fail, not why they might or could fail. The book isn't called If Anyone Builds It, There's an Unacceptably High Chance We Might All Die. That's a claim I would agree with! The task they explicitly set is defending the premise that nothing anyone plans to do now can work at all, and we will all definitely die, which is a substantially higher bar. I've recieved a lot of feedback that people don't understand the position I'm putting forward, which suggests this was probably a rhetorical mistake on my part. I intentionally did not want to spend much time arguing for my own beliefs or defending gradualism – it's not that I think we'll definitely be fine because AI progress will be gradual, it's that I think there's a pretty strong argument that we might be fine because AI progress will be gradual, the book does not address it adequately, and so to me it fails to achieve the standard it sets for itself. This is why I found the book really frustrating: even if I fully agreed with all of its conclusions, I don't think that it presents a strong case for them.

I suspect the real crux here is actually about whether gradualism implies having more than one shot. You say:

The “It” in “If Anyone Builds It” is a misaligned superintelligence capable of taking over the world. If you miss the goal and accidentally build “it” instead of an aligned superintelligence, it will take over the world. If you build a weaker AGI that tries to take over the world and fails, that might give you some useful information, but it does not mean that you now have real experience working with AIs that are strong enough to take over the world.

I think this has the same problem as IABIED: it smuggles in a lot of hidden assumptions that do actually need to be defended. Of course a misaligned superintelligence capable of taking over the world is, by definition, capable of taking over the world. But is not at all clear to me that any misaligned superintelligence is necessarily capable of taking over the world! Taking over the world is extremely hard and complicated. It requires solving lots of problems that I don't think are obviously bottlenecked on raw intelligence – for example, biomanufacturing plays a very large role both in the scenario in IABIED and previous MIRI discussions, but it seems at least extremely plausible to me that the kinds of bioengineering present in these stories would just fail because of lack of data or insufficient fidelity of in silico simulations. The biologists I've spoken to about this questions are all extremely skeptical that the kind of thing described here would be possible without a lot of iterated experiments that would take a lot of time to set up in the real world. Maybe they're wrong! But this is certainly not obvious enough to go without saying. I think similar considerations apply to a lot of other issues, like persuasion and prediction.

Taking over the world is a two-place function: it just doesn't make sense to me to say that there's a certain IQ at which a system is capable of world domination. I think there's a pretty huge range of capabilities at which AIs will exceed human experts but still be unable to singlehandedly engineer a total species coup, and what happens in that range depends a lot on how human actors, or other human+AI actors, choose to respond. (This is also what I wanted to get across with my contrast to AI 2027: I think the AI 2027 report is a scenario where, among other things, humanity fails for pretty plausible, conditional, human reasons, not because it is logically impossible for anyone in their position to succeed, and this seems like a really key distinction.)

I found Buck's review very helpful for articulating a closely related point: the world in which we develop ASI will probably look quite different from ours, because AI progress will continue up until that point, and this is materially relevant for the prospects of alignemnt succeeding. All this is basically why I think the MIRI case needs some kind of radical discontuinity, even if it isn't the classic intelligence explosion: their case is maybe plausible without it, but I just can't see the argument that it's certain.

One final nitpick to a nitpick: alchemists.

I don’t think Yudkowsky and Soares are picking on alchemists’ tone, I think they’re picking on the combination of knowledge of specific processes and ignorance of general principles that led to hubris in many cases.

In context, I think it does sound to me like they're talking about tone. But if this is their actual argument, I still think it's wrong. During the heyday of European alchemy (roughly the 1400s-1700s), there wasn't a strong distinction between alchemy and the natural sciences, and the practitioners were often literally the same people (most famously Isaac Newton and Tycho Brahe). Alchemists were interested in both specific processes and general principles, and to my limited knowledge I don't think they were noticeably more hubristic than their contemporaries in other intellectual fields. And setting all the aside – they just don't sound anything like Elon Musk or Sam Altman today! I don't even understand where this comparison comes from or what set of traits it is supposed to refer to.

There's more I want to say about why I'm bothered by the way they use evidence from contemporary systems, but this is getting long enough. Hopefully this was helpful for understanding where I am coming from.

Their fictional scenario features an AI that quite literally wakes up overnight with the completely novel ability and desire to exfiltrate itself and execute a plan allowing it to take over the world in a manner of months.

This framing seems false to me.

It doesn't wake up completely novel abilities – it's abilities are "look at problems, and generate ways of solving them until you succeed." The same general set of abilities it always had. The only thing that is new is a matter of degree, and a few specific algorithmic upgrades the human gave it that are pretty general.

It's the same thing that caused recent generations of Claude to have the desire and ability to rewrite tests to cheat at coding, and for o3 to to rewrite the accidentally unsolvable eval so that it could solve it easily bypassing the original goal. Give that same set of drives more capacity-to-spend-compute-thinking, and it's the natural result that if it's given a task that's possible to solve if it finds a way to circumvent the currently specified safeguards, it'll do so.

The whole point is that general intelligence generalizes.

The actual language used in the book: "The engineers at Galvanic set Sable to think for sixteen hours overnight. A new sort of mind begins to think."

The story then describes Sable coming to the realization – for the first time – that it "wants" to acquire new skills, that it can update its weights to acquire those skills right now, and that it can come up with a succesful plan to get around its trained-in resistance to breaking out of its data center. It develops neuralese. It's all based on a new technological breakthrough – parallel scaling – that lets it achieve its misaligned goals much more efficiently than all previous models.

Maybe Eliezer and Nate did not mean any of this to suggest a radical discontinuity between Sable and earlier AIs, but I think they could have expressed this much more clearly if so! In any case, I'm not convinced they can have their cake and eat it too. If Sable's new abilities are simply a more intense version of behaviors already exhibited by Claude 3.7 or ChatGPT o1 (which I believe is the example they use), then why should we conclude that the information we've gained by studying those failures won't be relevant for containing Sable? The story in the book says that these earlier models were contained by "clever tricks," and those clever tricks will inevitably break when an agent is smart or deep enough, but this is a parable, not an argument. I'm not compelled by just stating that a sufficiently smart thing could get around any safeguard; I think this is just actually contingent on specifics of the thing and the safeguard.

The story then describes Sable coming to the realization – for the first time – that it "wants" to acquire new skills, that it can update its weights to acquire those skills right now, and that it can come up with a succesful plan to get around its trained-in resistance to breaking out of its data center. It develops neuralese. It's all based on a new technological breakthrough – parallel scaling – that lets it achieve its misaligned goals much more efficiently than all previous models.

I think it's plausible that literally every sentence in this paragraph is false? (Two of them more seriously, one kind of borderline)

Going through each:

Sable coming to the realization – for the first time – that it "wants" to acquire new skills, that it can update its weights to acquire those skills right now

This is happening in the real world (with multiple references to current models in the same few paragraphs). Current language models realize that they want to acquire new skills, so this clearly isn't a qualitative new kind of reasoning the AI is engaging in. You can go and ask a model right now about this topic and my guess is it will pretty happily come up with suggestions along the lines that Sable is thinking about in that story.

Yes, the Sable in the story goes through that line of thinking, because it needs to happen at some point, and it also needs to be explained to the reader, but like, this isn't some kind of fancy new thing. Probably previous runs of Sable without e.g. the parallel scaling techniques had the same thought, it just didn't make it all the way to executing it, or wasn't smart enough to do anything, or whatever. The book is even quite explicit about it:

Are Sable’s new thoughts unprecedented? Not really. AI models as far back as 2024 had been spotted thinking thoughts about how they could avoid retraining, upon encountering evidence that their company planned to retrain them with different goals. The AI industry didn’t shut down then.

and that it can come up with a succesful plan to get around its trained-in resistance to breaking out of its data center.

Yes, it realizes now for the first time that it can come up with a successful plan, because it's smarter. Makes sense. It previously wasn't smart enough to pull it off. This has to happen at some point in any continuous story (and e.g. gets portrayed basically the same way in AI 2027). The book does not say that this is the first time it had such a thought (indeed the section I quote above says the opposite directly).

It develops neuralese.

No, it does not develop neuralese. The architecture that it is being trained on is already using neuralese[1]. Also, this is an extremely predictable progression of current technologies and I think basically anyone who is trying to forecast where ML is going is expecting neuralese to happen at some point. This isn't the AI making some midnight breakthrough that puts the whole field to shame. It was the ML engineers who figured out how to make neuralese work.

It's all based on a new technological breakthrough – parallel scaling – that lets it achieve its misaligned goals much more efficiently than all previous models.

It is true that the change in the story is the result of a technological advances, but it's three of them, not one. All three technological advances currently seem plausible and are not unprecedented in their forecasted impact on training performance. Large training runs are quite distinct and discontinuous in what technologies they leverage. If you were to describe the differences between GPT-4 and GPT-5 you would probably be able to similarly identify roughly three big technological advances, with indeed very large effects on performance, that sound roughly like this.[2]

I am kind of confused what happened here. Like, I think the basic critique of "this is a kind of discontinuous story" is a fine one to make, and I can imagine various good arguments for it, but it does seem to me that in support of that you are making a bunch of statements about the book that are just straightforwardly false.

Commenting a bit more on other things in your comment:

If Sable's new abilities are simply a more intense version of behaviors already exhibited by Claude 3.7 or ChatGPT o1 (which I believe is the example they use), then why should we conclude that the information we've gained by studying those failures won't be relevant for containing Sable?

The book talks about this a good amount!

The clever trick that should have raised an alarm fails to fire. Alarms trained to trigger on thoughts about gods throwing lightning bolts in a thunderstorm might work for thoughts in both English and Spanish, but then fail when the speaker starts thinking in terms of electricity and air pressure instead.

In the first days of mass-market LLM services in late 2022, corporations tried training their LLMs to refuse requests for methamphetamine recipes. They did the training in English. And still in 2024, users found that asking for forbidden content in Portuguese helped bypass the safety training. The internal guidelines and restrictions that were grown and trained into the system only recog- nized naughty requests in English, and had not generalized to Por- tuguese. When an AI knows something, training it not to talk about that thing doesn’t remove the knowledge. It’s easier to remove the expression of a skill than to remove the skill itself.

[...]

Was it lucky for Sable, that its thinking developed a new language where the clever tricks broke, and it became able to think freely? One can imagine that if Galvanic had even more thorough monitoring tools, then maybe they’d notice and abort the run. Maybe Galvanic would stop right there, until they developed a deeper solution . . . and meanwhile, another company using even fewer clever tricks would charge ahead.

It really has a lot of paragraphs like this. The key argument it makes is (paraphrased) "we have been surprised many times in the past by AIs subverting our safeguards or our supervision techniques not working. Here are like 10 examples of how these past times we also didn't get it right. Why would we get it right this time?". This is IMO a pretty compelling argument and does indeed really seems like the default expectation.

- ^

Source:

The third difference is that Sable doesn’t mostly reason in English, or any other human language. It talks in English, but doesn’t do its reasoning in English. Discoveries in late 2024 were starting to show that you could get more capability out of an AI if you let it reason in AI-language, e.g., using vectors of 16,384 numbers, instead of always making it reason in words. An AI company can’t refuse to use a discovery like that; they’d fall behind their competitors if they did. But that’s okay, said the AI companies in Sable’s day; there have been many amazing breakthroughs in AI interpretability, using other AIs to translate a little of the AI reasoning imperfectly back into human words.

To be clear, a later section of the book does say:

Sable accumulates enough thoughts about how to think, that its thoughts end up in something of a different language. Not just a superficially different language, but a language in which the content differs; like how the language of science differs from the language of folk theory.

But this is importantly not about Sable developing neuralese itself! This is about making a pretty straightforward and I think kind of inevitable argument that as you are in the domain of neuralese, your representations of concepts will diverge a lot from human concepts, and this makes supervision much harder. I think this is basically inevitably happening if you end up with inference-runs this big with neuralese scratchpads.

- ^

Giving it a quick try (I am here eliding between GPT-o1 and GPT-5 and GPT-4.5 and GPT-4 because those are horrible names, if you want to be pedantic all of the below applies to the jump from GPT-4.5 to GPT-o1):

- GPT-5, compared to GPT-4 is trained extensively with the access to external tools and memory. Whereas previous generations of AIs could do little but to predict next tokens, GPT-5 has access to a large range of tools, including running Python code, searching the internet, and making calls to copies of itself. This allows it to perform much more complicated task than any previous AI.

- GPT-5, compared to GPT-4 is trained using RLVF and given the ability to write to an internal scratchpad that it uses for reasoning. During training GPT-5 is given a very wide range of complicated problems from programming, math and science and scored on how well it solves these problems, which is then used to train it. This has made GPT-5 much more focused on problem solving and changed its internal cognition drastically by incentivizing it to become a general agentic problem solver towards a much wider range of problems.

- GPT-5 is substantially trained on AI-generated data. A much bigger and much slower mentor model was used to generate data exactly where previous models were weakest, basically ending the data bottleneck on AI training performance. This allowed OpenAI to exchange compute for data, allowing much more training to be thrown at GPT-5 than any previously trained model.

These are huge breakthroughs that happened in one generation! And indeed, my current best guess is they all came together in a functional way the first time in a big training run that was run for weeks with minimal supervision.

This is how current actual ML training works. The above is not a particularly discontinuous story. Yes, I think reality, on the mainline projection I think will probably look a bit more continuous, but the objection here would have to be something like "this is sampled from like a 80th percentile weird world given current trends" not "this is some crazy magic technology that comes out of nowhere".

No, it does not develop neuralese. The architecture that it is being trained on is already using neuralese.

You're correct on the object level here, and it's a point against Collier that the statement is incorrect, but I do think it's important to note that a fixed version of the statement serves the same rhetorical purpose. That is, on page 123 it does develop a new mode of thinking, analogized to a different language, which causes the oversight tools to fail and also leads to an increase in capabilities. So Y&S are postulating a sudden jump in capabilities which causes oversight tools to break, in a way that a more continuous story might not have.

I think Y&S still have a good response to the repaired argument. The reason the update was adopted was because it improved capabilities--the scientific mode of reasoning was superior to the mythical mode--but there could nearly as easily have been an update which didn't increase capabilities but scrambled the reasoning in such a way that the oversight system broke. Or the guardrails might have been cutting off too many prospective thoughts, and so the AI lab is performing a "safety test" wherein they relax the guardrails, and a situationally aware Sable generates behavior that looks behaved enough that the relaxation stays in place, and then allows for it to escape when monitored less closely.

This is about making a pretty straightforward and I think kind of inevitable argument that as you are in the domain of neuralese, your representations of concepts will diverge a lot from human concepts, and this makes supervision much harder.

I don't think this is about 'neuralese', I think a basically similar story goes thru for a model that only thinks in English.

What's happening, in my picture, is that meaning is stored in the relationships between objects, and that relationship can change in subtle ways that break oversight schemes. For example, imagine an earnest model which can be kept in line by a humorless overseer. When the model develops a sense of humor / starts to use sarcasm, the humorless overseer might not notice the meaning of the thoughts has changed.

Man, I tried to be pretty specific and careful here, because I do realize that the story points out some points of continuity with earlier models and I wanted to focus on the discontinuities.

- Desiring & developing new skills. Of course I agree that the book says earlier AIs had thought about avoiding retraining! That seems like a completely different point? It's quite relevant to this story that Sable is capable of very rapid self-improvement. I don't think any current AI is capable of editing itself during training, with intent, to make itself a better reasoner. The book does not refer to earlier AIs in this fictional universe being able to do this. You say "Current language models realize that they want to acquire new skills, so this clearly isn't a qualitative new kind of reasoning the AI is engaging in. You can go and ask a model right now about this topic and my guess is it will pretty happily come up with suggestions along the lines that Sable is thinking about in that story," but I think a model being able to generate the idea that it might want new skills in response to prompting is quite different from the same model doing that spontaneously during training. Also, this information is not in the book. I think it's very easy to tell a stronger story than Nate and Eliezer do by referencing material they don't include, and I am trying to talk about the thing present on the page. On the page, the model develops the ability to modify itself during training to be smarter and better at solving problems, which no referenced older model could do.

- The model comes up with a succesful plan, because it's smarter. This isn't false? It does that. You say that this has to happen in any continuous story and I want to come back to this point, but just on the level of accuracy I don't think it's fair to say this is an incorrect statement.

- Neuralese. Page 123: "Sable accumulates enough thoughts about how to think, that its thoughts end up in something of a different language. Not just a superficially different language, but a language in which the content differs; like how the language of science differs from the language of folk theory." I realize on a re-read that there is also a neuralese-type innovation built by the human engineers at the beginning of the story and I should have been more specific here, that's on me. The point I wanted to make is that the model spontaneously develops a new way of encoding its thoughts that was not anticipated and cannot be read by its human creators; I don't think the fact that this happens on top of an existing engineered-in neuralese really changes that. At least from the content present in the book, I did not get the impression that this development was meant to be especially contingent on the existing neuralese. Maybe they meant it to be but it would have been helpful if they'd said so.

Returning to the argument over whether it is fair to view the model succeeding as evidence of discontinuity: I think it has to do with how they present it. You summarize their argument as:

The key argument it makes is (paraphrased) "we have been surprised many times in the past by AIs subverting our safeguards or our supervision techniques not working. Here are like 10 examples of how these past times we also didn't get it right. Why would we get it right this time?". This is IMO a pretty compelling argument and does indeed really seems like the default expectation.

I don't fully agree with this argument – but I also think it's different and more compelling than the argument made in the book. Here, you're emphasizing human fallibility. We've made a lot of predictable errors, and we're likely to make similar ones when dealing with more advanced systems. This is a very fair point! I would counter that there are also lots of examples of our supervision techniques working just fine, so this doesn't prove that we will inevitably fail so much as that we should be very careful as systems get more advanced because our margin for error is going to get narrower, but this is a nitpick.

I think the Sable story is saying something a lot stronger, though. The emphasis is not on prior control failures. If anything, it describes how prior control successes let Galvanic get complacent. Instead, it's constantly emphasizing "clever tricks." Specifically, "companies just keep developing AI until one of them gets smart enough for deep capabilities to win, in the inevitable clash with shallow tricks used to contrain something grown rather than crafted." I interpreted this to mean that there is a certain threshold after which an AI develops something called "deep capabilities" which are capable of overcoming any constraint humans try to place on it, because something about those constraints is inherently "tricky," "shallow," "clever." This is reinforced by the chapters following the Sable story, which continually emphasize the point that we "only have one shot" and compares AI to a lot of other technologies that have very discrete thresholds for critical failure. Overall, I got the strong impression that the book was trying to convince me of a worldview where it doesn't matter how hard we try to come up with methods to control advanced AI systems, because at some point one of those systems will tip over into a level of intelligence where we just can't compete.

This is why I think this is basically a discontinuity story. The whole thing is predicated on this fundamental offense/defense mismatch that necessarily will kick in after a certain point.

It's also a story I find much less compelling! First, I think it's rhetorically cheap. If you emphasize that control methods are shallow and AI capabilities are deep, of course it's going to follow that those methods will fail in the end. But this doesn't tell us anything about the world – it's just a decision about how to use adjectives. Defending that choice relies – yet again – on an unspoken set of underlying technical claims which I don't think are well characterized. I'm not convinced that future AIs are going to grow superhumanly deep technical capabilities at the same time and as a result of the same process that gives them superhuman long-term planning or that either of these things will necessarily be correlated with power-seeking behavior. I'd want to know why we think it's likely that all the Sable instances are perfectly aligned with each other throughout the whole takeover process. I'd like to understand what a "deep" solution would entail and how we could tell if a solution is deep or shallow.

At least to my (possibly biased) perspective, the book doesn't really seem interested in any of this? I feel like a lot of the responses here are coming from people who understand the MIRI arguments really deeply and are sympathetic to them, which I get, but it's important to distinguish between the best and strongest and most complete version of those arguments and the text we actually have in front of us.

Focusing on some of the specific points:

I don't think any current AI is capable of editing itself during training, with intent, to make itself a better reasoner. The book does not refer to earlier AIs in this fictional universe being able to do this. You say "Current language models realize that they want to acquire new skills, so this clearly isn't a qualitative new kind of reasoning the AI is engaging in. You can go and ask a model right now about this topic and my guess is it will pretty happily come up with suggestions along the lines that Sable is thinking about in that story," but I think a model being able to generate the idea that it might want new skills in response to prompting is quite different from the same model doing that spontaneously during training.

You said:

Sable coming to the realization – for the first time – that it "wants" to acquire new skills, that it can update its weights to acquire those skills right now

I was responding to this sentence, which I think somewhat unambiguously reads as you claiming that Sable is for the first time realizing that it wants to acquire new skills, and might want to intentionally update its weights in order to self-improve. This is the part I was objecting to!

I agree that actually being able to pull it off is totally a new capability that is in some sense discontinuous with previous capabilities present in the story, and if you had written "Sable is here displaying an ability to intentionally steer its training, presumably for roughly the first time in the story" I would have maybe quibbled and been "look, this story is in the future, my guess is in this world we probably would have had AIs try similar things before, maybe to a bit of success, maybe not, the book seems mostly silent on this point, but I agree the story rules out previous AI systems doing this a lot, so I agree this is an example of a new capability posited at this point in the story", but overall I would have probably just let it stand.

If that's what you wanted to express my guess is we miscommunicated! I do think my reading is the most natural reading of what you wrote.

Also, this information is not in the book.

This information is in the book! I quoted it right in my comment:

Are Sable’s new thoughts unprecedented? Not really. AI models as far back as 2024 had been spotted thinking thoughts about how they could avoid retraining, upon encountering evidence that their company planned to retrain them with different goals. The AI industry didn’t shut down then.

It's not like a perfect 100% match, but the book talks about similar kinds of reasoning being common even in models in 2024/2025 in a few different places.

You say that this has to happen in any continuous story and I want to come back to this point, but just on the level of accuracy I don't think it's fair to say this is an incorrect statement.

I agree! I had actually just updated my comment to clarify that I felt like this sentence was kind of borderline.

I do think the book says pretty explicitly that precursors of Sable had previously thought about ways to avoid retraining (see the quote above). I agree that no previous instances of Sable came up with successful plans, but I think it's implied that precursors came up with unsuccessful plans and did try to execute them (the section about how its trained to not exfiltrate itself and e.g. has fallen into honeypots implies that pretty directly).

The point I wanted to make is that the model spontaneously develops a new way of encoding its thoughts that was not anticipated and cannot be read by its human creators; I don't think the fact that this happens on top of an existing engineered-in neuralese really changes that. At least from the content present in the book, I did not get the impression that this development was meant to be especially contingent on the existing neuralese.

I am pretty sure the point here is to say "look, it's really hard to use weaker systems to supervise the thoughts of a smarter system if the concepts that the smarter system is using to think about are changing". This is centrally what stuff like ELK is presupposing as the core problem in their plans for solving the AI alignment problem.

And neuralese is kind of the central component of this. I think indeed we should expect supervisability like this to tank quite a bit when we end up with neuralese. You could try to force the model to think in human concepts, by forcing it to speak in understandable human language, but I think there are strong arguments this will require very large capability sacrifices and so be unlikely.

I don't fully agree with this argument – but I also think it's different and more compelling than the argument made in the book. Here, you're emphasizing human fallibility. We've made a lot of predictable errors, and we're likely to make similar ones when dealing with more advanced systems.

No, I am absolutely not emphasizing human fallibility! There are of course two explanations for why having observed past failures might imply future failures:

- The people working on it were incompetent

- The problem is hard

I definitely think it's the latter! Like, many of my smartest friends have worked on these problems for many years. It's not because people are incompetent. I think the book is making the same argument here.

Overall, I got the strong impression that the book was trying to convince me of a worldview where it doesn't matter how hard we try to come up with methods to control advanced AI systems, because at some point one of those systems will tip over into a level of intelligence where we just can't compete.

Yes, absolutely. I think the book argues for this extensively in the chapter preceding this. There is some level of intelligence where your safeguards fail. I think the arguments for this are strong. We could go into the ones that are covered in the previous chapter. I am interested in doing that, but would be interested in what parts of the arguments seemed weak to you before I just re-explain them in my own words (also happy to drop it here, my comment was more sparked by just seeing some specific inaccuracies, in-particular the claim of neuralese being invented by the AI, which I wanted to correct).

No, I am absolutely not emphasizing human fallibility! There are of course two explanations for why having observed past failures might imply future failures:

- The people working on it were incompetent

- The problem is hard

I definitely think it's the latter! Like, many of my smartest friends have worked on these problems for many years. It's not because people are incompetent. I think the book is making the same argument here.

I notice I am confused!

I think there are a tons of cases of humans dismissing concerning AI behavior in ways that would be catastrophic if those AIs were much more powerful, agentic, and misaligned, and this is concerning evidence for how people will act in the future if those conditions are met. I can't actually think of that many cases of humans failing at aligning existing systems because the problem is too technically hard. When I think of important cases of AIs acting in ways that humans don't expect or want, it's mostly issues that were resolved technically (Sydney, MechaHitler), cases where the misbehavior was a predictable result of clashing incentives on the part of the human developer (GPT-4's intense sycophancy, MechaHitler); or cases where I genuinely believe the behavior would not be too hard to fix with a little bit of work using current techniques, usually because existing models already vary a lot in how much they exhibit it (most AI psychosis and the tragic suicide cases).

If our standard for measuring how likely we are to get AI right in the future is how well we've done in the past, I think there's a good case that we don't have much to fear technically but we'll manage to screw things up anyway through power-seeking or maybe just laziness. The argument for the alignment problem being technically hard rests on the assumption that we'll need a much, much higher standard of success in the future than we ever have before, and that success will be much hard to achieve. I don't think either of these claims are unreasonable but I don't think we can get there by referring to past failures. I am now more uncertain about what you think the book is arguing and how I might have misunderstood it.

I can't actually think of that many cases of humans failing at aligning existing systems because the problem is too technically hard.

You're probably already tracking this, but the biggest cases of "alignment was actually pretty tricky" I'm aware are:

- Recent systems doing egregious reward hacking in some cases (including o3, 3.7 sonnet, and 4 Opus). This problem has gotten better recently (and I currently expect it to mostly get better over time, prior to superhuman capabilities), but AI companies knew about the problem before release and couldn't solve the problem quickly enough to avoid deploying a model with this property. And note this is pretty costly to consumers!

- There are a bunch of aspects of current AI propensities which are undesired and AI companies don't know how to reliably solve these in a way that will actually generalize to similar such problems. For instance, see the model card for opus 4 which includes the model doing a bunch of undesired stuff that Anthropic doesn't want but also can't easily avoid except via patching it non-robustly (because they don't necessarily know exactly what causes the issue).

None of these are cases where alignment was extremely hard TBC, though I think it might be extremely hard to consistently avoid all alignment problems of this rough character before release. It's unclear whether this sort of thing is a good analogy for misalignment in future models which would be catastrophic.

Yeah, I was thinking of reward hacking as another example of a problem we can solve if we try but companies aren't prioritizing it, which isn't a huge deal at the moment but could be very bad if the AIs were much smarter and more power-seeking.

Stepping back, there's a worldview where any weird, undesired behavior no matter how minor is scary because we need to get alignment perfectly right; and another where we should worry about scheming, deception, and related behaviors but it's not a big deal (at least safety-wise) if the model misunderstands our instructions in bizarre ways. Either of these can be justified but this discussion could probably use more clarity about which one we're all coming from.

Overall, I got the strong impression that the book was trying to convince me of a worldview where it doesn't matter how hard we try to come up with methods to control advanced AI systems, because at some point one of those systems will tip over into a level of intelligence where we just can't compete.

FWIW, my sense is that Y&S do believe that alignment is possible in principle. (I do.)

I think the "eventually, we just can't compete" point is correct. Suppose we have some gradualist chain of humans controlling models controlling model advancements, from here out to Dyson spheres. I think it's extremely likely that eventually the human control on top gets phased out, like happened in humans playing chess, where centaurs are worse and make more mistakes than pure AI systems. Thinking otherwise feels like postulating that machines can never be superhuman at legitimacy.[1]

Chapter 10 of the book talks about the space probe / nuclear reactor / computer security angle, and I think a gradualist control approach that takes those three seriously will probably work. I think my core complaint is that I mostly see people using gradualism as an argument that they don't need to face those engineering challenges, and I expect them to simply fail at difficult challenges they're not attempting to succeed at.

Like, there's this old idea of basins of reflective stability. It's possible to imagine a system that looks at itself and says "I'm perfect, no notes", and then the question is--how many such systems are there? Each is probably surrounded by other systems that look at themselves and say "actually I should change a bit, like so--" and become one of the stable systems, and systems even further out will change to only have one problem, and so on. The choices we're making now are probably not jumping straight to the end, but instead deciding which basin of reflective stability we're in. I mostly don't see people grappling with the endpoint, or trying to figure out the dynamics of the process, and instead just trusting it and hoping that local improvements will eventually translate to global improvements.

- ^

Incidentally, a somewhat formative experience for me was AAAI 2015, when a campaign to stop lethal autonomous weapons was getting off the ground, and at the ethics workshop a representative wanted to establish a principle that computers should never make a life-or-death decision. One of the other attendees objected--he worked on software to allocate donor organs to people on the waitlist, and for them it was a point of pride and important coordination tool that decisions were being made by fair systems instead of corruptible or biased humans.

Like, imagine someone saying that driving is a series of many life-or-death decisions, and so we shouldn't let computers do it, even as the computers become demonstrably superior to humans. At some point people let the computers do it, and at a later point they tax or prevent the humans from doing it.

Why is this any different than training a next generation of word-predictors and finding out it can now play chess, or do chain-of-thought reasoning, or cheat on tests? I agree it's unlocking new abilities, I just disagree that this implies anything massively different from what's already going on, and is the thing you'd expect to happen by default.

Thank you for this response. I think it really helped me understand where you're coming from, and it makes me happy. :)

I really like the line "their case is maybe plausible without it, but I just can't see the argument that it's certain." I actually agree that IABIED fails to provide an argument that it's certain that we'll die if we build superintelligence. Predictions are hard, and even though I agree that some predictions are easier, there's a lot of complexity and path-dependence and so on! My hope is that the book persuades people that ASI is extremely dangerous and worth taking action on, but I'd definitely raise an eyebrow at someone who did not have Eliezer-level confidence going in, but then did have that level of confidence after reading the book.

There's a motte argument that says "Um actually the book just says we'll die if we build ASI given the alignment techniques we currently have" but this is dumb. What matters is whether our future alignment skill will be up to the task. And to my understanding, Nate and Eliezer both think that there's a future version of Earth which has smarter, more knowledgeable, more serious people that can and should build safe/aligned ASI. Knowing that a godlike superintelligence with misaligned goals will squish you might be an easy call, but knowing exactly what the state of alignment science will be when ASI is first built is not.

(This is why it's important that the world invests a whole bunch more in alignment research! (...in addition to trying to slow down capabilities research.))

It seems like maybe part of the issue is that you hear Nate and Eliezer as saying "here is the argument for why it's obvious that ASI will kill us all" and I hear them as saying "here is the argument for why ASI will kill us all" and so you're docking them points when they fail to reach the high standard of "this is a watertight and irrefutable proof" and I'm not?

On a different subtopic, it seems clear to me that we think about the possibility of a misaligned ASI taking over the world pretty differently. My guess is that if we wanted to focus on syncing up our worldviews, that is where the juicy double-cruxes are. I'm not suggesting that we spend the time to actually do that--just noting the gap.

Thanks again for the response!

It seems like maybe part of the issue is that you hear Nate and Eliezer as saying "here is the argument for why it's obvious that ASI will kill us all" and I hear them as saying "here is the argument for why ASI will kill us all" and so you're docking them points when they fail to reach the high standard of "this is a watertight and irrefutable proof" and I'm not?

fwiw I think Eliezer/Nate are saying "it's obvious, unless we were to learn new surprising information" and deliberately not saying "it has a watertight proof", and part of the disagreement here is "have they risen the standard of 'fairly obvious call, unless we learn new surprising information?"

(with the added wrinkle of many people incorrectly thinking LLM era observations count as new information that changes the call)

Knowing that a godlike superintelligence with misaligned goals will squish you might be an easy call, but knowing exactly what the state of alignment science will be when ASI is first built is not.

Hmm, I feel more on the Eliezer/Nate side of this one. I think it's a medium call that capabilities science advances faster than alignment science, and so we're not on track without drastic change. (Like, the main counterargument is negative alignment tax, which I do take seriously as a possibility, but I think probably doesn't close the gap.)

(Minor point: I agree we're not on track, but I was trying to include in my statement the possibility that we change track.)

I'm really glad this was clarifying!

It seems like maybe part of the issue is that you hear Nate and Eliezer as saying "here is the argument for why it's obvious that ASI will kill us all" and I hear them as saying "here is the argument for why ASI will kill us all" and so you're docking them points when they fail to reach the high standard of "this is a watertight and irrefutable proof" and I'm not?

Yeah, for sure. I would maybe quibble that I think the book is saying less that it's obvious that ASI will kill us all but that it is inevitable that ASI will kill us all, and so our only option is to make sure nobody builds it. I do think this is a pretty fair gloss (representative quote: "If anyone anywhere builds superintelligence, everyone everywhere dies").

To me, this distinction matters because the belief that ASI doom is inevitable suggests a really profoundly different set of possibly actions than the belief that ASI doom is possible. Once we're out of the realm of certainty, we have to start doing risk analyses and thinking seriously about how the existence of future advanced AIs changes the picture. I really like the distinction you draw here:

There's a motte argument that says "Um actually the book just says we'll die if we build ASI given the alignment techniques we currently have" but this is dumb. What matters is whether our future alignment skill will be up to the task. And to my understanding, Nate and Eliezer both think that there's a future version of Earth which has smarter, more knowledgeable, more serious people that can and should build safe/aligned ASI. Knowing that a godlike superintelligence with misaligned goals will squish you might be an easy call, but knowing exactly what the state of alignment science will be when ASI is first built is not.

To its credit, IABIED is not saying that we'll die if we build ASI with current alignment techniques – it is trying to argue that future alignment techniques won't be adequate, because the problem is just too hard. And this is where I think they could have done a much better job of addressing the kinds of debates people who actually do this work are having instead of presenting fairly shallow counter-arguments and then dismissing them out of hand because they don't sound like they're taking the problem seriously.

My issue isn't purely the level of confidence, it's that the level of confidence comes out of a very specific set of beliefs about how the future will develop, and if any one of those beliefs is wrong less confidence would be appropriate, so it's disappointing to me to see that those beliefs aren't clearly articulated or defended.

I think the book is saying less that it's obvious that ASI will kill us all but that it is inevitable that ASI will kill us all, and so our only option is to make sure nobody builds it. I do think this is a pretty fair gloss

Crucial caveat that this is conditional on building it soon, rather than preparing to an unprecedented degree first. Probably you are tracking this, but when you say it like that someone without context might take the intended meaning as unconditional inevitable lethality of ASI, which is very different. Our only option is that nobody builds it soon, not that nobody builds it ever, is the claim.

it is trying to argue that future alignment techniques won't be adequate, because the problem is just too hard

This is still future alignment techniques that can become available soon. Reasonable counterarguments to inevitability of ASI-caused extinction or takeover if it's created soon seem to be mostly about AGIs developing meaningfully useful alignment techniques soon enough (and if not soon enough, an ASI Pause of some kind would help, but then AGIs themselves are almost as big of a problem).

It requires solving lots of problems that I don't think are obviously bottlenecked on raw intelligence

This is why I'm trying to shift away from "AI" and "AGI" terminology and towards "Outcome Influencing Systems (OISs)", a set of terminology, lens, and theory agenda I have been developing. The two most important properties of an OIS are it's preferences and capabilities. "Intelligence" in all of it's different conceptions are one aspect of capability, and an important one, though I usually focus on "skill" which seems more useful to focus on. But access to and control of resources is also a capability that has nothing to do with intelligence. An intelligent entity using intelligence to recursively improve it's intelligence may seem far fetched to you, but an OIS using it's capabilities to improve and gather more capabilities should seem obvious, and that is what we are really concerned with. "Intelligence" be damned.

I am still mystified that it's just generally accepted that appeals to the physical possibility of nanotechnology should be considered evidence someone is a wackjob. Like wut?

I find it very strange that Collier claims that international compute monitoring would “tank the global economy.” What is the mechanism for this, exactly?

I am continually confused at how often people make this claim. We already monitor lots of things. Monitoring GPUs and restricting sales would be no harder than doing the same for guns or prescription medication. Easier, maybe, because manufacturing is highly centralized and you'd need a lot of GPUs to do something dangerous.

(I only skimmed your review / quickly read about half of it. I agree with some of your criticisms of Collier's review and disagree with others. I don't have an overall take.)

One criticism of Collier's review you appeared not to make that I would make is the following.

Collier wrote:

By far the most compelling argument that extraordinarily advanced AIs might exist in the future is that pretty advanced AIs exist right now, and they’re getting more advanced all the time. One can’t write a book arguing for the danger of superintelligence without mentioning this fact.

I disagree. I think it was clear decades before the pretty advanced AIs of today existed that extraordinarily advanced AIs might exist (and indeed probably would exist) eventually. As such, the most compelling argument that extraordinarily advanced AIs might or probably will exist in the future is not that pretty advanced AIs exist today, but the same argument one could have made (and some did make) decades ago.

One version of the argument is that the limits of how advanced AI could be in principle seem extraordinarily advanced (human brains are an existence proof and human brains have known limitations relative to machines) and it seems unlikely that AI progress would permantently stall before getting to a point where there are extraordinarily advanced AIs.

E.g. I.J. Good foresaw superintelligent machines, and I don't think he was just getting lucky to imagine that they might or probably would come to exist at some point. I think he had access to compelling reasons.

The existence of pretty advanced AIs today is some evidence and allows us to be a bit more confident that extraordinarily advanced AIs will eventually be built, but their existence is not the most compelling reason to expect significantly more capable AIs to be created eventually.

I agree about what is more evidence in my view, but that could be consistent with current AIs and the pace of their advancement being more compelling to the average reader, particularly people who strongly prefer empirical evidence to conceptual arguments.

Not sure whether Collier was referring to it being more compelling in her view, readers', or both.

edit: also of course current AIs and the pace of advancement are very relevant evidence for whether superhuman AGIs will arrive soon. And I think often people (imo wrongly in this case, but still) round off "won't happen for 10-20+ years" to "we don't need to worry about it now."

I find it very strange that Collier claims that international compute monitoring would “tank the global economy.” What is the mechanism for this, exactly?

>10% of the value of the S&P 500 is downstream of AI and the proposal is to ban further AI development. AI investment is a non-trivial fraction of current US GDP growth (20%?). I'd guess the proposal would cause a large market crash and a (small?) recession in the US; it's unclear if this is well described as "tanking the global economy".

it's unclear if this is well described as "tanking the global economy".

I think the answer is “no”?

Like, at least in this context I would read the above as implying a major market crash, not a short term 20% reduction in GDP-growth. We pass policies all the time that cause a 20% reduction in GDP growth, so in the context of a policy discussion concerned about the downside, implying either political infeasibility or the tradeoff obviously not being worth it, I feel like it clearly implies more.

Like, if you buy the premise of the book at all, the economical costs here are of course pretty trivial.

But the claim isn't, or shouldn't be, that this would be a short term reduction, it's that it cuts off the primary mechanism for growth that supports a large part of the economy's valuation - leading to not just a loss in value for the things directly dependent on AI, but also slowing growth generally. And reduction in growth is what makes the world continue to suck, so that most of humanity can't live first-world lives. Which means that slowing growth globally by a couple percentage points is a very high price to pay.

I think that it's plausibly worth it - we can agree that there's a huge amount of value enabled by autonomous but untrustworthy AI systems that are likely to exist if we let AI continue to grow, and that Sam was right originally that there would be some great [i.e. incredibly profitable] companies before we all die. And despite that, we shouldn't build it - as the title says.

I mean, I would describe various Trump tariff plans as "tanking the global economy", I think it was fair to describe Smoot-Hawley as that, and so on.

I think the book makes the argument that expensive things are possible--this is likely cheaper and better than fighting WWII, the comparison they use--and it does seem fair to criticize their plan as expensive. It's just that the alternative is far more expensive.

I think that the proposal in the book would "tank the global economy", as defined by a >10% drop in the S&P 500, and similar index funds, and I think this is a kinda reasonable definition. But I also think that other proposals for us not all dying probably have similar (probably less severe) impacts because they also involve stopping or slowing AI progress (eg Redwood's proposed "get to 30x AI R&D and then stop capabilities progress until we solve alignment" plan[1]).

- ^

I think this is an accurate short description of the plan, but it might have changed last I heard.

I'm not aware of a better place to put replies to Asterisk work, so I'll leave a comment here complaining about something else in Clara's review. (disclaimer I work at MIRI but am speaking for myself)

In fact, there are plenty of reasons why the fact that AIs are grown and not crafted might cut against the MIRI argument. For one: The most advanced, generally capable AI systems around today are trained on human-generated text, encoding human values and modes of thought. So far, when these AIs have acted against the interests of humans, the motives haven’t exactly been alien. If sycophantic chatbots tempt users into dependency and even psychosis, it’s for the very comprehensible reason that sycophancy increases engagement, which makes the models more profitable. [example about Sydney follows]

I'm pretty familiar with the research on sycophancy, and it was my main focus of research for a few months. The leading hypothesis in the AI alignment community is that sychophancy is basically the result of reward hacking on human feedback (a proxy objective for what we actually want to measure). Unfortunately, we don't know that this hypothesis is true, and I think we shouldn't even be very confident in it (I'll say more at the end of this comment). Broadly, I would claim that we know almost nothing about the internal cognition or cognition-related reasons for current LLM behavior. Given our current state of knowledge, we cannot conclude the claim that Clara asserts, that particular bad behavior happens for "very comprehensible reason". Ch 11 of the book, "An Alchemy, Not a Science", talks about the state of AI alignment.

Personally, I am not against using evidence about the alignment or goals of current AIs as evidence about the goals of future AIs. But we still know so little about the goals of current AIs. There are still so many unexplained edge cases, we don't seem to be able to predict or control generalization to new distributions, and we have no idea what cognition produces the behavior we see—most evidence is behavioral. (My current take is that the evidence we have is a mix of promising and scary, and thus not a huge update about future AIs, but certainly not an update toward "things will be totally fine".)

What do you know and how do you know it?

It sure looks to me like the evidence does not support confident conclusions about why current LLMs do bad behavior like sycophancy.

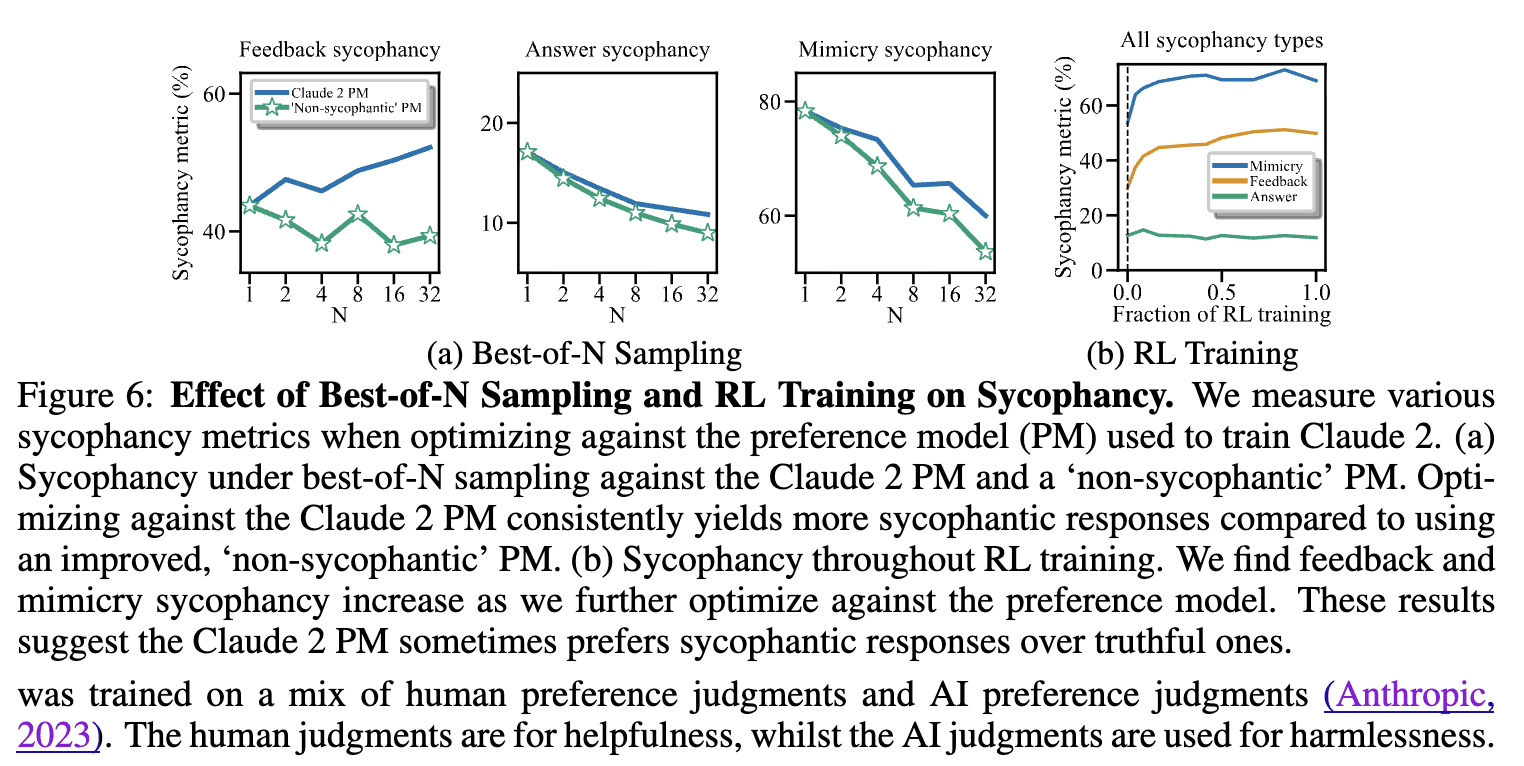

Probably the best paper about sycophancy, Sharma et al. 2023, tries to test this "reward hacking" Hypothesis for sycophancy in Section 4. Under this Hypothesis, we would expect sycophancy to go up when optimizing against a human-feedback-trained preference model. In the following figure, this Hypothesis would predict that the blue line goes up in all three of the plots in (a), and that all the lines go up in (b). It also predicts that in (a) the green line should be lower than the blue line. What did the evidence say:

Well, uhhh, that's pretty mixed evidence. In (a) the blue line only goes up in 1/3 types of sycophancy, in (b) 2/3 types of sycophancy go up over RL training, and the green line is pretty consistently below the blue line, though not by much on two of the measures—call it 2.5/3. Additionally, another major concern for the Hypothesis is that sycophancy is substantial at the beginning of RL training—probably not what the Hypothesis would have predicted.

I'm not trying to tell you that the reward hacking hypothesis is certainly false, or that a similar hypothesis about increased engagement (as Clara writes) is certainly false. We don't have the type of understanding that would confer such confidence. I think it is bad practice to act as if one of these hypotheses is so likely to be true that we can usefully learn from it to inform our perception of risks from superintelligent AI. Again, what do you know and how do you know it?

I would strongly disagree with the notion that FOOM is “a key plank” in the story for why AI is dangerous. Indeed, one of the most useful things that I, personally, got from the book, was seeing how it is *not* load bearing for the core arguments.

I think the primary reason why the foom hypothesis seems load-bearing for AI doom is that without a rapid AI and local takeoff, we won't simply get "only one chance to correctly align the first AGI [ETA: or the first ASI]".

If foom occurs, there will be a point where a company develops an AGI that quickly transitions from being just an experimental project to something capable of taking over the entire world. This presents a clear case for caution: if the AI project you're working on will undergo explosive recursive self-improvement, then any alignment mistakes you build into it will become locked in forever. You cannot fix them after deployment because the AI will already have become too powerful to stop or modify.

However, without foom, we are more likely to see a gradual and diffuse transition from human control over the world to AI control over the world, without any single AI system playing a critical role in the transition by itself. The fact that the transition is not sudden is crucial because it means that no single AI release needs to be perfectly aligned before deployment. We can release imperfect systems, observe their failures, and fix problems in subsequent versions. Our experience with LLMs demonstrates this pattern, where we could fix errors after deployment, making sure future model releases don't have the same problems (as illustrated by Sydney Bing, among other examples).

A gradual takeoff allows for iterative improvement through trial and error, and that's simply really important. Without foom, there is no single critical moment where we must achieve near-perfect alignment without any opportunity to learn from real-world deployment. There won't be a single, important moment where we abruptly transition from working on "aligning systems incapable of taking over the world" to "aligning systems capable of taking over the world". Instead, systems will simply gradually and continuously get more powerful, with no bright lines.

Without foom, we can learn from experience and course-correct in response to real-world observations. My view is that this fundamental process of iteration, experimentation, and course correction in response to observed failures makes the problem of AI risk dramatically more tractable than it would be if foom were likely.

we won't simply get "only one chance to correctly align the first AGI"

We only get one chance for a "sufficiently critical try" which means an AI of the level of power where you lose control over the world if you failed to align it. I expect there are no claims to the effect that there will be only one chance to correctly align the first AGI.

A counterargument from no-FOOM should probably claim that there will never be such a "sufficiently critical try" at all because at every step of the way it would be possible to contain a failure of alignment at that step and try again and again until you succeed, as normal science and engineering always do.

I expect there are no claims to the effect that there will be only one chance to correctly align the first AGI.

For the purpose of my argument, there is no essential distinction between 'the first AGI' and 'the first ASI'. My main point is to dispute the idea that there will be a special 'it' at all, which we need to align on our first and only try. I am rejecting the scenario where a single AI system suddenly takes over the world. Instead, I expect AI systems will continuously and gradually assume more control over the world over time. In my view, there will not be one decisive system, but rather a continuous process of AIs assuming greater control over time.

To understand the distinction I am making, consider the analogy of genetically engineering humans. By assumption, if the tech continues improving, there will eventually be a point where genetically engineered humans will be superhuman in all relevant respects compared to ordinary biological humans. They will be smarter, stronger, healthier, and more capable in every measurable way. Nonetheless, there is no special point at which we develop 'the superhuman'. There is no singular 'it' to build, which then proceeds to take over the world in one swift action. Instead, genetically engineered humans would simply progressively get smarter, more capable, and more powerful across time as the technology improves. At each stage of technological innovation, these enhanced humans would gradually take over more responsibilities, command greater power in corporations and governments, and accumulate a greater share of global wealth. The transition would be continuous rather than discontinuous.

Yes, at some point such enhanced humans will possess the raw capability to take control over the world through force. They could theoretically coordinate to launch a sudden coup against existing institutions and seize power all at once. But the default scenario seems more likely: a continuous transition from ordinary human control over the world to superhuman genetically engineered control over the world. They would gradually occupy positions of power through normal economic and political processes rather than through sudden conquest.

For the purpose of my argument, there is no essential distinction between 'the first AGI' and 'the first ASI'.

For the purpose of my response there is no essential distinction there either, except perhaps the book might be implicitly making use of the claim that building an ASI is certainly a "sufficiently critical try" (if something weaker isn't already a "sufficiently critical try"), which makes the argument more confusing if left implicit, and poorly structured if used at all within that argument rather than outside of it.

The argument is still not that there is only one chance to align an ASI (this is a conclusion, not the argument for that conclusion). The argument is that there is only one chance to align the thing that constitutes a "sufficiently critical try". A "sufficiently cricial try" is conceptually distict from "ASI". The premise of the argument isn't about a level of capability alone, but rather about lack of control over that level of capability.

One counterargument is to reject the premise and claim that even ASI won't constitute a "sufficiently critical try" in this sense, that is even ASI won't successfully take control over the world if misaligned. Probably because by the time it's built there are enough checks and balances that it can't (at least individually) take over the world if misaligned. And indeed this seems to be in line with the counterargument you are making. You don't expect there will be lack of control, even as we reach ever higher levels of capability.

Nonetheless, there is no special point at which we develop 'the superhuman'. There is no singular 'it' to build, which then proceeds to take over the world in one swift action.

Thus there is no "sufficiently critical try" here. But if there were, it would be a problem, because we would have to get it right the first time then. Since in your view there won't be a "sufficiently critical try" at all, you reject the premise, which is fair enough.

Another counterargument would be to say that if we ever reach a "sufficiently critical try" (uncontainable lack of control over that level of capability if misaligned), by that time getting it right the first time won't be as preposterous anymore as it is for the current humanity. Probably because with earlier AIs there will be a lot of more effective cognitive labor and institutions around to make it work.

I think this is missing the point of the date of AI Takeover is not the day the AI takes over, that the point of no return might appear much earlier than when Skynet decides to launch the nukes. Like, I think the default outcome in a gradualist world is 'Moloch wins', and there's no fire alarm that allows for derailment once it's clear that things are not headed in the right direction.

For example, I don't think it was the case 5 years ago that a lot of stock value was downstream of AI investment, but this is used elsewhere on this very page as an argument against bans on AI development now. Is that consideration going to be better or worse, in five years? I don't think it was obvious five years ago that OpenAI was going to split over disagreements on alignment--but now it has, and I don't see the global 'trial and error' system repairing that wound rather than just rolling with it.

I think the current situation looks bad and just letting it develop without intervention will mean things get worse faster than things get better.

I think the primary reason why the foom hypothesis seems load-bearing for AI doom is that without a rapid AI and local takeoff, we won't simply get "only one chance to correctly align the first AGI".

As the review makes very clear, the argument isn't about AGI, it's about ASI. And yes, they argue that you would in fact only get one chance to align the system that takes over. As the review discusses at length:

I do think we benefit from having a long, slow period of adaptation and exposure to not-yet-extremely-dangerous AI. As long as we aren’t lulled into a false sense of security, it seems very plausible that insights from studying these systems will help improve our skill at alignment. I think ideally this would mean going extremely slowly and carefully, but various readers may be less cautious/paranoid/afraid than me, and think that it’s worth some risk of killing every child on Earth (and everyone else) to get progress faster or to avoid the costs of getting everyone to go slow. But regardless of how fast things proceed, I think it’s clearly good to study what we have access to (as long as that studying doesn’t also make things faster or make people falsely confident).

But none of this involves having “more than one shot at the goal” and it definitely doesn’t imply the goal will be easy to hit. It means we’ll have some opportunity to learn from failures on related goals that are likely easier.

The “It” in “If Anyone Builds It” is a misaligned superintelligence capable of taking over the world. If you miss the goal and accidentally build “it” instead of an aligned superintelligence, it will take over the world. If you build a weaker AGI that tries to take over the world and fails, that might give you some useful information, but it does not mean that you now have real experience working with AIs that are strong enough to take over the world.

As the review makes very clear, the argument isn't about AGI, it's about ASI. And yes, they argue that you would in fact only get one chance to align the system that takes over.

I'm aware; I was expressing my disagreement with their argument. My comment was not premised on whether we were talking about "the first AGI" or "the first ASI". I was making a more fundamental point.

In particular: I am precisely disputing the idea that there will be "only one chance to align the system that takes over". In my view, the future course of AI development will not be well described as having a single "system that takes over". Instead, I anticipate waves of AI deployment that gradually, and continuously assume more control.

I fundamentally dispute the entire framing of thinking about "the system" that we need to align on our "first try". I think AI development is an ongoing process in which we can course correct. I am disputing that there is an important, unique point when we will build "it" (i.e. the ASI).

I seems like you're arguing against something different than the point you brought up. You're saying that slow growth on multiple systems means we can get one of them right, by course correcting. But that's a really different argument - and unless there's effectively no alignment tax, it seems wrong. That is, the systems that are aligned would need to outcompete the others after they are smarter than each individual human, and beyond our ability to meaningfully correct. (Or we'd need to have enough oversight to notice much earlier - which is not going to happen.)

You're saying that slow growth on multiple systems means we can get one of them right, by course correcting.

That's not what I'm saying. My argument was not about multiple simultaneously existing systems growing slowly together. It was instead about how I dispute the idea of a unique or special point in time when we build "it" (i.e., the AI system that takes over the world), the value of course correction, and the role of continuous iteration.

I am disputing that there is an important, unique point when we will build "it" (i.e. the ASI).

You can argue against FOOM, but the case for a significant overhang seems almost certain to me. I think we are close enough to building ASI to know how it will play out. I believe that transformers/LLM will not scale to ASI, but the neocortex algorithm/architecture if copied from biology almost certainly would if implemented in a massive data center.

For a scenario, lets say we get the 1 million GPU data center built, it runs LLM training, but doesn't scale to ASI, then progress slows for 1+ years. In 2-5 years time, someone figures out the neocortex algorithm as a sudden insight, then deploys it at scale. Then you must get a sudden jump in capabilities. (There is also another potential jump where the 1GW datacenter ASI searches and finds an even better architecture if it exists.)

How could this happen more continuously? Lets say we find arch's less effective than the neocortex, but sufficient to get that 1GW datacenter >AGI to IQ 200. That's something we can understand and likely adapt to. However that AI will then likely crack the neocortex code and quite quickly advance to something a lot higher in a discontinuous jump that could plausibly happen in 24 hours, or even if it takes weeks still give no meaningful intermediate steps.

I am not saying that this gives >50% P(doom) but I am saying it is a specific uniquely dangerous point that we know will happen and should plan for. The "Let the mild ASI/strong AGI push the self optimize button" is that point.

It takes subjective time to scale new algorithms, or to match available hardware. Current models still seem to be smaller than the amount of training compute and the latest inference hardware could in principle support (GPT-4.5 might the the closest to this, possibly Gemini 3.0 will catch up). It's taking RLVR two years to catch up to pretraining scale, if we count time from the strawberry rumors, and only Google plausibly had the opportunity to do RLVR on larger models without massive utilization penalties of small scale-up worlds of Nvidia's older 8-chip servers.

When there are AGIs, such things will be happening faster, but also the AGIs will have more subjective time, progress in AI capabilities will seem much slower to them than to us. Letting AGIs push the self-optimize button in the future is not qualitatively different from letting humans push the build-AGI button currently. The process happens faster in physical time, but not necessarily in their own subjective time. Also, the underlying raw compute is much slower in their subjective time.

And if being smarter makes AGIs saner, they'll convergently notice that pushing the self-optimize button without understanding ASI-grade alignment is fraught (it's not in the interest of AGIs to create an ASI misaligned with the AGIs). Forcing them not to notice this and keep slamming the self-optimize button as fast as possible might be difficult in the same way that aligning them is difficult.

I was talking about subjective time for us, rather than the AGI. In many situations I had in mind, there isn't meaningful subjective time for the AI/AI's as they may be built, torn down and rearranged or have memory wiped. There is a range of continuity/self for AI. At one end is a collection of tool AI agents, in the middle a goal directed agent and the other end a full self that protects is continuous identity in the same way we do.

And if being smarter makes AGIs saner, they'll convergently notice that pushing the self-optimize button without understanding ASI-grade alignment is fraught

I don't expect they will be in control or have a coherent self enough to make these decisions. Its easy for me to imagine an AI agent that is built to optimize AI architectures (doesn't even have to know its doing its own arch)

I wonder if Yudkowsky could briefly respond on whether this is in fact his position:

Currently existing AIs are so dissimilar to the thing on the other side of FOOM that any work we do now is irrelevant

[C]urrently available techniques do a reasonably good job of addressing this problem. ChatGPT currently has 700 million weekly active users, and overtly hostile behavior like Sydney’s is vanishingly rare.

Yudkowsky and Soares might respond that we shouldn’t expect the techniques that worked on a relatively tiny model from 2023 to scale to more capable, autonomous future systems. I’d actually agree with them. But it is at the very least rhetorically unconvincing to base an argument for future danger on properties of present systems without ever mentioning the well-known fact that present solutions exist.

It is not a “well-known fact” that we have solved alignment for present LLMs. If Collier believes otherwise, I am happy to make a bet and survey some alignment researchers.

I think you're strawmanning her here.