Back in 2021 when image generators like DALL-E arrived, I was more astonished than most that they could turn descriptions into realistic pictures. For anyone who’s tried creating a convincing fake photograph themselves by piecing together and adjusting existing photographs using software like Adobe Photoshop (without AI tools), will find it virtually impossible to do. Merely producing convincing lighting (with plausible colour temperature and illumination/shadows) is very difficult. Let alone the ray-tracing required to create a photorealistic 3D view from an arbitrary angle, which almost no human can do manually with such software; at best a skilled artist could take hours to produce a semi-realistic picture of a simple scene.

For AI to be able to do this convincingly, it surely needs a sophisticated understanding of the 3D world (rotation, perspective, lighting, etc - ideally full ray-tracing, plus other physics and pragmatics), which is (almost?) impossible to infer just from a load of photographs (ie 2D images) with captions/descriptions.

Indeed I heard that neural networks intrinsically can’t infer these kinds of complex mathematical transformations; also that, as their output is a superposition of their training data (existing photographs), they can’t create arbitrary scenes either.

So how do they manage to do all of this so well, or at all? (Quite aside from the near-miracle of inferring the very oblique relationship between training images and text descriptions of them.)

Oddly I haven’t seen anyone raise this question, let alone provide a satisfactory answer.

Indeed I heard that neural networks intrinsically can’t infer these kinds of complex mathematical transformations; also that, as their output is a superposition of their training data (existing photographs), they can’t create arbitrary scenes either.

Citation very much needed. It sure seems to me like image models have an understanding of 3d space e.g. asking vision models to style transfer to depth/normal maps shouldn't work if they don't understand 3d space

Not the way you think. You are seeing the mask and trying to understand it, while ignoring the shoggoth underneath.

The topic has gotten a lot of discussion, but from the relevant context of the shoggoth, not the irrelevant point of the mask. Every post about how do we know when AI is telling the truth vs repeating what is in training data, the talk of p-zombies, etc. that is all directly struggling with your question.

Edit: to be clear, I am not saying the fact ais make mistakes shows they're inhuman, I am saying look at the mistake and ask yourself what does the fact that the ai made this specific mistake and not a different one tell you about why the ai thought the mistake was correct /edit

Here is an example. Alpha go beat all the best players in the world at go. They described its thinking as completely alien and they were emotionally distraught at how badly they lost. A couple months later multiple mediocre players obliterated it repeatedly and reliably. It turned out the AI didn't know it was playing a game that had a board with conditions that persisted from turn to turn, it didn't/doesn't understand that there are fields that are controlled with pieces inside. It can figure out the best next move without that understanding. It now wins all the time again. But it still doesn't understand the context. There is no way to confirm it knows it is playing a game.

Going directly at images, why are you so sure dalle knows what an image is or what it is doing? Why do you think it knows there is a person looking at its output vs an electric field pulsing in a non random way? Does it understand we see red but not infrared? Is it adding details only tetrachromate can see? No one has the answers to these questions. No one has a technique that has a plausible method of working to get the answers.

Your image prompt might be creating a pattern in binary, or hexadecimal color codes, but it is probably a bizarre set of tokens that fit like Cthulhu-esque jigsaw pieces in a mosaic using more relationships than human minds can comprehend. I saw a claim that chatgpt 4 broke language out into a 36,000+ dimensional table of relationships. It ain't using hooked on phonics but it certainly can trick you into believing it does. That tricking you is the mask. The 36,000 dimensional map of language is part of the shoggoth, not the whole thing.

To make the mask slip in images give it tasks that rely on relationships not facades. For example, and I apologize if you are easily offended, do a search on hyper muscle growth. You will get porn, sorry. But in it you will find images with impossible mass and realistic internal anatomy. The artists understand skeletons and where muscle attaches to limbs. Drop some of the most extreme art into sora or nano banana or grok and animate it. The skeletons lose all coherence. The facade, the skin and limbs move, but what is going on inside cannot be. Skeletons don't do what the image generators will try, because they can't see the invisible. And skeletons are invisible. For a normally proportioned human that's irrelevant, but for an impossible proportion it is. 3d artists draw skeleton wireframes then layer polygons above it so the range of motion fits plwhat is possible and correct. AI copies the training data and extrapolates. Impossible shapes cause the mask to slip, you sent doesn't know what a body is it thinks we're blobs that move and have precise shapes.

Monsters are another one. Try a displacer beast, this is a cat with six legs, four that comport to the shape of traditional feline front legs and two that are rear legs, plus it has two tentacles coming off its shoulders that are like the arms (not tentacles) of a squid with the barbed diamond shaped pads. The difference between tentacle motion and leg motion is unknown to AI because it relies on what is unseen, the skeleton underneath. Again, it think a monster is a blob that moves.

Getting to your architecture, this you see in window and door placement. There is no understanding of the relationship or the 3d nature of the space. Instead it knows walls have doors and windows and doors are more likely down low and windows are more likely up high. So it adds them. But it doesn't understand space or function.

When you see people talk about AI slop articles using the it's not x it's y pattern or triplets or em dashes, this is the same topic. This is how the AI knows what it knows. Why it thinks that is good writing, but uses it in ways humans don't even though it got the pattern out of human made training data. Same topic, different application.

People really are talking about it a lot

There is no understanding of the relationship or the 3d nature of the space.

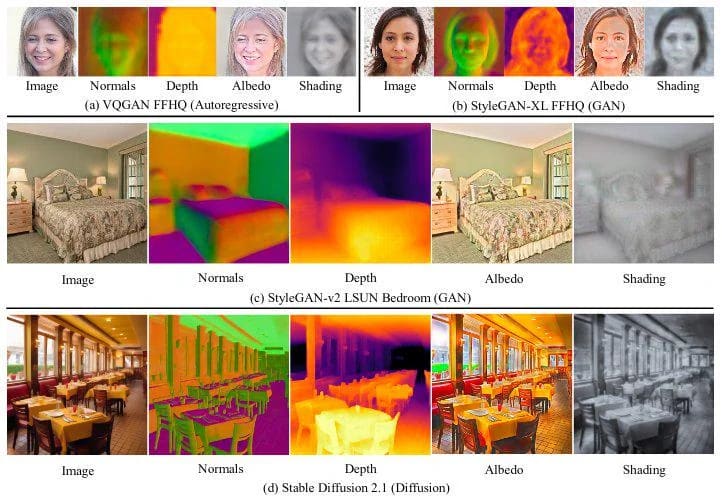

I don't think you can claim that. Research has repeatedly shown that image generators like stable diffusion carry strong representations of depth and geometry, such that performant depth estimation models can be built out of them with minimal retraining. This continues to be true for video generation models.

Early work on the subject: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2409.09144

So do you think this is part of how it generates images - i.e. having used depth estimation and much else to infer 3D objects/scenes and the wider workings of the 3D world from its training photographs, it turns a new description into an internal representation of a 3D scene and then renders it to photorealistic 2D using inter alia a kind of reversal of its 2D->3D inference algorithm???

Which seems miraculous to me - not so much that this is possible, but that a neural network figured this all out by itself rather than the complex algorithms required being very elaborately hand-coded.

I would have assumed that at best a neural network would infer a big pile of kludges that would produce poor results, like a human trying to Photoshop a bunch of different photographs together.

Yes, that's what I'm implying. We don't have super concrete evidence for it, but a large contingent of researchers (including myself) believes things like that are happening.

To understand why neural networks might do this, you can view them as a sort of Solomonoff induction. The neural network is a "program" (similar to a python program written in code) that has to model its data as well as possible, but the model is only so big, which means that the program is limited in length. Thinking about how you might write a program to generate images, it would be much more code-efficient to write abstractions and rules for things like geometry than it would be to enumerate every possibility. The training/optimization algorithm figures that out also.

You might also be interested in emergent world representations [1] (models simulate the underlying processes or "world" that generates their data in order to predict it) and the platonic representation hypothesis [2] (different models trained on seperate modalities like text and images form similar representations, meaning that an image model will represent a picture of a dog in a similar way to how a text model will represent the word "dog").

why are you so sure dalle knows what an image is or what it is doing? Why do you think it knows there is a person looking at its output vs an electric field pulsing in a non random way?

I don’t think it does (and didn’t say this!)

My question is how it manages to produce, almost all the time, such convincing 3D images without knowing about the 3D world and everything else normally required to create a realistic 3D image. As you can’t just do it by fitting together existing loosely suitable photographs (from its training data) and tweaking the results.

I don’t deny that you can catch it out by asking for weird things very different from its training data (though it often makes a good attempt). However that doesn’t explain how it does so well at creating images which are broadly within the range of its training data, but different enough from the photographs it’s seen that a skilled human with Photoshop couldn’t do what it does.

I watched all 7 hours of Dominic Cummings' testimony to parliament yesterday on the UK government response to COVID. (Cummings was the Prime Minister’s top adviser.)

Key points he made that are relevant to rationalists (some hardly mentioned by the media):

- Groupthink throughout government and its SAGE committee of scientific advisers meant their initial plan - no lockdown, await herd immunity - wasn't abandoned soon enough. Psychological 'memes' - that Britons wouldn't accept lockdowns or track & trace - were believed with little basis. The groupthink was broken in part by Cummings seeking an outside view of technical documents from Demis Hassabis and Tim Gowers (interestingly).

- Institutional design failure means incompetent people get promoted to leadership and decision-making roles in UK government and political parties. Various highly competent individuals in more junior ranks were sidelined and left. People aren't incentivized to do the right things. Cummings said he himself shouldn't have been in such a high-powered job, which should have been held by someone far more intelligent & capable. (Cummings was in fact considered the smartest person in Downing St, though he lacks a technical background.)

- Weak planning for catastrophes, e.g. poor access to data, inability to circumvent slow bureaucratic procedures, lack of detailed advance plans and lines of responsibility for them. He mentioned anthrax attacks and solar flares as other potential scenarios.

- Human challenge trials should have occurred early on - perhaps even in Jan 2020.

Overall I found him a credible witness, because his testimony was very detailed (e.g. he recalled numerous dates of meetings & events), and quite self-critical, blaming himself for not forcing a lockdown sooner, and for not resigning at various points. His analysis above also seems sound.

I’ve belatedly realised that a lot of professionals - maybe even the majority - are somewhat corrupt. Doctors, financial advisers, lawyers, architects, etc. will give incorrect advice, treatment and so on purely in order to extract more money from you. For example, by giving unnecessary blood tests, recommending a high-commission investment, stringing out a legal case instead of trying to settle it, using an expensive builder with whom they have a cosy relationship.

Indeed it’s unusual to find a professional acting for you in a way that is clearly against their own financial interests, eg by trying to save you money. Fortunately I reckon customers notice when this happens, so these unusually honest professionals acquire a good reputation (if they are also competent). Which serves them quite well, as people want to keep giving them work - if their rates are reasonable - and recommend them to others.

In my 20s I was happy to pay a lot to get advice from an expert, reckoning that you get what you pay for, so paying more gets you better advice. But that’s only partly true. With a dishonest expert, you’ll probably end up with a good result, but via a circuitous route you will overpay for - extra for their expertise, plus extra for their particular way of ripping you off.

That said, I suspect this corruption is more common in mediocre professionals, who unlike experts find it harder to earn a lot by honest work. But I have encountered dishonest experts too.

The only way of avoiding all this is for the professional’s incentives to be aligned with yours, which is often impossible, particularly due to the standard charging structures of many professions (eg per hour, or % of your spend, rather than on results), which create perverse incentives that they have no interest in changing. (Not long ago I abandoned an architect who refused to charge for his input other than as a % of building cost, while trying to interest me in absurdly expensive stairs, getting his carpenter friend to quote double normal price for windows, meanwhile assuring me he was from a humble, honest family etc.)

Until I realised all the above recently (in my 50s!) I had assumed, as many do, that dodgy behaviour was unusual in middle class professions, and was instead associated with plumbers, builders, car mechanics and (in the UK anyway) real estate agents. But now I am suspicious of anyone who charges money for services.

It’s a shame.

I 100% agree about financial advisors, but I am less sure about the doctors. (Not enough experience with the lawyers.) These are the differences between the professions that I think could be responsible:

Idealism: Some kids dream about becoming doctors because "helping other people heal" is intuitive. Even if they later get somewhat corrupt, at least they started from a good position. On the other hand, people doing finance are usually there specifically for the money. (Doing it for idealistic reasons is possible in theory, but requires an effective altruism kind of mindset, which is rare in the population.)

Temptation: How much money does a corrupt doctor make compared to a honest one? Twice as much, maybe. A honest financial advisor? Probably can't even find client. So possibly a few orders of magnitude difference.

Regulation: Depends on the country, but there are some checks on doctors, however dysfunctional those may be. For financial advisors, giving bad advice is the state of art; almost no one gives good advice.

Also, not sure why, but in my experience there seems to be a generational difference: older plumbers etc. are more likely to do a good job and ask for less money.

I am pretty sure there are honest and well-meaning financial advisors too. E.g. there are valid and professional blogs/youtube channels (e.g. "The Plain Bagel"). There are some confounding factors though, in particular, pretty much anyone can call himself a financial advisor. Even if they do not know anything about finance and their only goal is to sell overpriced insurance policies.

Sure. I found one for my parents, who seems honest and gave no more advice than necessary. I suspect honest financial advisers are often individuals or small practices rather than larger firms.

(In the UK, financial advisers are (now) heavily regulated - you can’t just call yourself one.)

Re doctors, in the UK I suspect a key distinction is between NHS (state-funded) vs private patients. The NHS pays them reasonable salaries, but consultants (senior doctors) can earn far more from private patients and tend to have a mixture of both. I suspect they treat NHS patients as fulfilling their moral duty, and private patients as a cash cow (especially as their fees are usually paid by insurance companies) - giving unnecessary treatment to rich people. In my limited experience of private doctors they barely tried to disguise this attitude towards me.

I think honest financial advisors earn a decent living in the UK. The situation changed radically after the 2009 financial crash as high commissions on investments rightly became illegal, removing the main corrupt incentive. Before this happened and when I was less savvy, I certainly got ripped off this way.

I suspect the generational difference may be age as much as generation. Older tradespeople may have accumulated savings, so less need to earn lots, and have matured in their attitudes towards customers as people.

Out of curiosity I once joined an OVB training for financial advisors, but I concluded that there was no way to do this ethically (and make nonzero money). Long story short, your reward depends on the recommendations you give to your clients. The worse the advice, the greater the commission.

Of course no one tells you explicitly to give bad advice, but they discourage you from asking too many questions (the excuse is something like: if you keep doing this, one day you will understand), I think they won't give you the exact formula for calculating your reward, but they give you enough hints that selling life insurance is where most of the reward comes from. (The reward for everything else is a rounding error; a service you do only so that you can plausibly say that you are not an insurance salesman.) Like, it's okay to help people get mortgage, or even invest money in funds (note: their recommended funds always lose money, no matter which direction the economy goes)... but, you know, the really important thing is to "create a financial plan" for your client, which always includes pressing them to spend about 1/3 on their salary on life insurance, regardless of their circumstances. Because that is where your commission comes from.

A honest financial advisor, for starters, couldn't be paid by commission; that's already the opposite of alignment, because the worst products have highest commissions (basically they are paying you to help them scam people, by sharing a part of the profit), and the small commissions would result in very low hourly income for you (considering how much time would you spend talking to the client, how many clients would refuse your advice, etc.). A more honest model is to ignore the commission and just get paid by hour of consultation. There, at least you don't have an incentive to actively give bad advice. (You still don't have much of an incentive to give good advice, though.)

A good, plausible movie about AI risk might be an indirect way to raise the chance of government action via public awareness (if that would be useful). Have there been such AI risk movies that I've missed? If not, how could people get one to happen?

Cf I get the impression governments take asteroid risks a bit more seriously thanks to various asteroid-strike movies over the years. Not least the recent Don't Look Up on Netflix, which despite being a comedy was probably quite thought-provoking to many viewers (e.g. showing how there could well be government & public denial, resulting in disaster).

When reading Superintelligence by Nick Bostrom it struck me parts of it would make excellent movie plots. Eg the AI's ingenious ways of escaping an AI box by social engineering. (Though, googling, I see that a dire-looking romcom called Superintelligence, perhaps inspired by but very far removed from the book, was released in 2020.)

While not for activist reasons, more for entertainment, I have a general outline in my head about a realistic thriller movie about a quantitative finance company that accidentally comes up with AGI. The plot follows a security consultant who is called in; they don't really know what's happening at first and they think it's a hacker, but it also could be a bug, they're not sure... Kind of writes itself really.

'Up to' is a misleading rhetorical device widely used in marketing, politics, etc. It precedes a statistic that is an impressive or scary maximum, where some kind of average would almost always be the relevant figure instead. So I'm immediately suspicious of any claim containing the phrase 'up to'.

Eg broadband providers that quote maximum speeds (that only a few optimally-located customers might get in the early hours of the morning) instead of averages. IIRC the UK's advertising regulator has banned this particular trick.

Indeed maxima are often nearly meaningless, such as 'up to x% of COVID cases result in death'. Why not a single figure? In practice it may mean something like: among various studies, the highest estimate produced was x%. (So why not give the range, or just the average?) Or it means something almost irrelevant, like: among various unstated categories of people, the highest figure is x% - likely to be a small, unrepresentative subgroup (e.g. aged over 90, or those with BMI > 30).

I can't be the only person who's noticed this rhetorical device everywhere (I haven't checked), though I've never read/heard anyone else mention it.

Why do almost all showers have different user interfaces, and bad ones at that? Eg unclear how to turn it on (especially if there is a separate shower head and hand-operated hose), which way is hot, and how hot the current setting is. Each shower requires experimentation to figure it out. How hard can this really be? Even premium manufacturers like Grohe fail.

which way is hot

Some faucets have little red/blue symbols to show hot/cold water, but it's not universal. I wish it was.

Even then it’s often ambiguous what is meant. If you have a single handle (on a faucet or shower) which is rotated to adjust temperature, it’s often unclear whether it’s the position of the part of the handle you hold or the other end (which moves in the opposite direction) that indicates the desired temperature

Hmm ...

Most people use the same shower every day, so they only have to learn a new shower UI when they move to a different house (or are visiting someone, etc.) Ease of first use and ease of habitual use are not the same target. Once a user has learned a particular shower UI, they can probably operate it half-asleep.

Once installed, a shower stays in operation a long time. I've used showers that were 50+ years old in the past year. (Contrast with cars, which have an average lifespan of 12 years.) So even if there was some massively better shower UI developed today, that was so great that 100% of new showers used it, for most people it would remain unfamiliar for a long time.

Because of the long lifespan of showers, any "beneficial mutation" (UI improvement) would take a long time to reach fixation. So showers evolve slowly, aesthetic design trends may overrule functional improvements, and knowledge may get lost: maybe the best shower UI design of 50 years ago is not available today because it was tied to a particular 1970s aesthetic.

Indeed it’s ease of first use I’m thinking of here. Noticeable when staying in hotels.

But I doubt aesthetics are relevant in the case of shower UI though - surely a good UI would be aesthetically pleasing enough. And UI design for such a simple device shouldn’t require evolution over time - could jump straight to a (near-)optimal solution

There seems a big contradiction in the position of environmentalists who support animal rights (as almost all do). They say we shouldn’t eat meat because animals, and animal feed, contribute to CO2 emissions. But if we didn't eat meat, the animals we breed for that purpose wouldn’t exist.

Surely animal rights include the right to life. So denying billions of cows & chickens any life at all seems a strongly anti-animal position.

While meat production involves killing animals, at least they get some life. And if (a big 'if') they were well treated, so they'd enjoy the life they do get, that's a good deal for the animals. Because they'd be much better off than in the wild - a grim existence of starvation, disease, fear, and being torn to bits by predators. And they'd also be better off than not existing.

(The environmentalist assumption that life in the wild is good - because 'nature is good' - doesn't follow. Life in the natural state - e.g. the Stone Age - is nasty, brutish, and short. Human history is the struggle to escape the natural state.)

So, CO2 aside, my position is that meat eating is fine as long as the animals are well treated. Which would mean more expensive meat, and less of it, but that's OK. Happy cows are better than no cows.

(At this point some people object that 'the demand for meat is so high that it can't be met while treating the animals well' - but that ignores that demands don't have to be met; if supply is restricted by a welfare requirement, prices will rise accordingly, so only those who can afford to pay for happy cows will eat steak. It's like saying 'billions of people would want a private jet, so unless we ban private jets they'll all get one'. Well, they would if they cost $10, but not if they cost $10 million.)

I guess one important question not raised here (but lurking in unspoken assumptions) is whether it is better for 1000 animals to be killed after about 3 months on average, or for 50 animals to live an average of 5 possibly painful years each in the wild.

If you scaled up for humans (1000 humans each killed at 3 years old versus 50 humans living to an average of 60) it seems obvious, but that's probably a false equivalency.

I'd split the first case into two:

- (a) Current meat production: 1000 animals poorly treated and killed young for cheap meat

- (b) My ideal: (say) 200 animals very well treated and killed, preferably not quite so young, for expensive meat.

Then if we call your 50 wild animals case (c), my claim is that:

- b > c (as more animals, better conditions, and maybe not much shorter lifespan, but probably more total life-years anyway, and more happiness x years); and

- b > a (assuming (a) involves conditions worse than, or not much better than, non-existence).

I'm not sure what position you're taking here.

"Right to life" doesn't mean "right to have as many individuals of some group brought into existence as physically possible". It usually means more like "a living individual has a right to not be killed". If you're interpreting it as the former, then it seems to me that you're grossly misinformed about what people actually mean by the term.

In theory some position of total utilitarianism might lead to something along the lines you imply, but even that would have to be traded off against other possible ways of increasing whatever total utility function is being proposed. Most such theories are incompatible with "right to life" in either sense.

I do agree with part of your argument, but think it would have been better stated alone, and not following from and in conjunction with a complete strawman.

My position is in the penultimate paragraph.

OK it looks like I didn't understand what people mean by 'right to life' - probably because I'm inclined towards consequentialism, so don't understand or believe in rights-talk.

However I think an analogous argument could be made along the lines of a 'right to reproduce' (which I suspect many might reckon exists). Non-existent animals don't have the right to exist per se, but their parents have a right to reproduce, which would make them exist.

Cf in the human sphere, mass forced sterilization (of an ethnic group, say) would no doubt be deemed a form of genocide - i.e. infringing something similar to a right to life.

Cf 'right to family life'

Yes, there is an idea of "right to reproduce", but hardly anyone believes that it should hold for animals in the sense of your article. The exceptions seem mainly to apply to critically endangered species.

Rather a lot of people don't hold "right to reproduce" in unrestricted form for humans either. It certainly doesn't have the same near-universality as human right to life.

While mass forced sterilization of particular ethnic groups is absolutely a form of genocide, this again goes way beyond any analogous beliefs that animal rights people hold. Nobody is saying that all chickens and cows should be sterilized so that their species becomes extinct. The closest it gets is "stop force-breeding them".

I didn’t mean make them extinct. I meant not let them reproduce freely, and control their numbers by sterilisation and culling. If done to a severe extent (which may not be necessary in the case of food animals) I can see an analogy with genocide.

(Cf though I’m not an animal rights activist in any way, even as a child I thought there was something odd about the mass extermination of coypu in the UK merely because they ate crops.)

Having the right to live tends to mean the right not to be killed once you exist. It doesn't generally mean all possible lives need to be brought into existence. The nonexistent kids of people who decided not to have any, or not to have as many kids as was physically possible are perfectly well off as far as that goes.

Neolithic innovations are pretty far beyond the natural state, and parts of human history like intensive agriculture may have resulted in worse experiences at an individual level while still being necessary to survive the situation or other pressures. History doesn't always march to something more pleasant. Stone age humans in general probably had much more capable social structures and healing ability than most wild animals have to look forward to - what nonhuman society can both set a broken bone so it will heal right and look after the creature healing?

It doesn't generally mean all possible lives need to be brought into existence.

1. A living animal has a right to life.

2. A living species has a right to life. This isn't the same thing as 'all possible lives need to be brought into existence'.

2 is similar to my reply above about 'right to reproduce'. Sounds like you mean the right not to go extinct (re which arguments for biodiversity would also apply); though it's not likely that cows & chickens would actually go extinct if meat production were banned.

OK I guess this is the 'person-affecting view' I've heard slightly about - that nothing is lost by animals/people not being brought into existence. No doubt this is gone into far greater depth in population ethics etc (of which I know little), but my gut response would be that by not being brought into existence the potential animals in question are missing out, even though they don't know they are. As their potential happiness is being prevented. We might say, the world is missing their happiness.

If Stone Age people were happier than wild animals, that only strengthens my case. And I expect in the Stone Age they weren't happy at all, by modern standards, if we consider the least happy current country in the world (Afghanistan), whose people rate themselves 2.5 on a 0-10 scale, which is around 'barely worth living' (worse than death being considered below about 2). I assume levels of suffering from violence, disease, injury, cold and starvation were typically higher in Stone Age societies then in present Afghanistan, hence happiness lower. And wild animals' 'happiness' lower still.

While I have a position on the case - I'd rather eat lab-grown meat and conduct trades with other animals that don't involve their suffering and slaughter, even if that results in somewhat fewer lives barely worth living existing in the first place - I wasn't arguing against it with that point, rather thinking that your view of the stone age and human progress may benefit from challenging some of the assumptions to it.

Peoples' level of happiness and peoples' level of suffering are somewhat distinct, for one. For happiness, there are baseline levels, hedonic adaptation, adjusting to the situation, deliberate abuse... I can tweak my baseline happiness upward, but I don't necessarily want to.

People in Afghanistan and other modern places have versions of suffering available to them that would have been far less available in the (early especially) stone age, including weapons technology for war, the ability to muster state violence in a significant degree and other political innovations, chemical pollution and the physical risks specifically of heavy machinery, having people a continent away readily able to offset their reduction in suffering by inflicting the externalities to you ... I think it is reasonable to look into the idea of whether levels of suffering actually were higher in Stone Age societies on a by person level. (Ones in regions where it never gets cold would likely not have higher levels of suffering from cold, as a trivial example...)

(Edit, additionally to address first paragraph)

For person-affecting view - Some is lost by animals and people not being brought into existence, but I don't feel like it has much ethical implication short of when that is actually genocidal, which is group-level ethics rather than individual.

The fact the infinite combinations of genes and experiences I could possibly have grown from are missing out on experiencing life is a much less serious tragedy to me than the suffering of any person who actually exists.

If I was one of a set of possible embryos selected from to deliberately not have benign or at least survivable traits because society discriminates against (for example) left-handed people, I'd have somewhat more concerns.

Re Stone Age suffering, as you probably know, violence has been in long-term big decline, and much higher in non-states than states:

https://slides.ourworldindata.org/war-and-violence/#/title-slide

Life expectancy at birth in Afghanistan is 64, which is 2 or 3 times in the Stone Age. Suggesting worse general health back then, with attendant suffering. (Infant deaths are of course a substantial part of the lower life expectancy, but by no means all.)

Indeed there's a wider ranges of potential causes of suffering now, but I'm not convinced they're worse overall. E.g. being shot is not clearly worse than being stabbed. People are rarely burnt at the stake now. Chemical pollution is fairly new, but there were plenty of other poisons before. Disease/death from air pollution is predominantly a problem of non-industrial societies (from cooking over open fires), not cars etc.

And of course modern medicine provides ways of alleviating suffering, via treatments and anaesthetics, mostly unavailable in the Stone Age (though at least to some extent available in Afghanistan).

Two comments:

There could be something that is at least deontologically iffy about killing gigantic numbers of sentient beings for comparatively pedestrian purposes. If one isn't completely certain of consequentialism, then that might weigh into ones considerations.

It also seems much less likely that animals are going to be treated well enough than for factory farming to be outlawed and/or superseded by clean meat. This is kind of answered by your answer to the hypothetical objection in your last paragraph, though.

Re your first point, indeed, though if one believes in deontology, hence in rights, you may also think there's something iffy about denying many sentient beings happy lives (ended by painless deaths), which is what I argue they should have. (And there is no plausible middle ground in which cows & chickens would be bred in large numbers and well treated but not eaten - i.e. get to live the lives of pets.)

Re your second point, I can envisage a scenario in which factory farming (i.e. conditions that make animals unhappy) is outlawed, and/or meat is mostly superseded by lab/plant products, but much smaller amounts of expensive happy animal meat are still produced, because (a) it tastes better (or has better texture etc.) to most people, or (b) to a few people, or (c) has sufficient cachet & signalling value (e.g. due to rarity/price) that it is treated as if it tastes better.

(And there is no plausible middle ground in which cows & chickens would be bred in large numbers and well treated but not eaten - i.e. get to live the lives of pets.)

The key word in that sentence is probably 'in large numbers'. However, this seems to ignore the fact that:

- 'Pets' don't usually produce food. (The prior sentence might be false.)

- Both uses can coexist (leaning more towards eating than not, while instances of not still exist).

- How many chickens would there be if everyone had a chicken? (More seriously, extrapolating from the past, what's the upper bound on chicken population, under the 'lots of people have (a few) chickens' model?)

Not sure what you mean by 'both uses can coexist' - i.e. a chicken treated as a pet then eaten? Unlikely.

You may have more of a point re people owning a hen as a kind of pet (i.e. well treated) in order to lay eggs, rather than be eaten; as some people of course already do. I can see that could become more widespread.

Not sure what you mean by 'both uses can coexist' - i.e. a chicken treated as a pet then eaten? Unlikely.

Multiple chickens owned, most eaten, one (particularly useful one) treated more like a (working) pet.

as some people of course already do

I think this used to be more common that it is today.

Cf very surprisingly, a few years ago Princess Anne, a noted horse-rider who competed in the Olympics, called for horses to be eaten so as to improve their welfare. (I.e. so those unsuitable, or no longer suitable, for riding still have a value.) She said this in a speech for the World Horse Welfare charity, of which she is president.

Regulations around backyard chickens have been kind of a hotly argued issue in my locality in my lifetime, so that trend is not necessarily always voluntary or irreversible.

(Regarding 'wild' animals and middle ground, people may also decide to do things like build birdhouses, provide feeders, and treat injury, which may enhance quality/length of life without making either lifestock or pet of those interacted with. Populations of feral chickens also exist some places, so farm-raised chickens aren't the only group in consideration for farm-chicken-descended birds.)

When scientists first realised an atomic bomb might be feasible (in the UK in 1939), and how important it would be, the UK defence science adviser reckoned there was only a 1 in 100,000 chance of successfully making one. Nonetheless the government thought that high enough to instigate secret experiments into it.

(Obliquely relevant to AI risk.)

On that topic, I'm interested to understand what scientists building the bombs thought about the morality of building them. Were they thinking about where or how it will be used at all? I'm trying to construct a parallel between the psychology of researchers around AI today and atomic bombs in the past. Not sure if there are any good accounts on this: The Brighter than a Thousand Suns book received pretty poor feedback, so I'm hesitant to trust it.

According to the Wikipedia article above, the Frisch–Peierls memorandum included those two scientist’s suggestion that the best way to deal with their concern that the Germans would develop an atomic bomb was to build one first. But what they thought about the moral issues I don’t know

I’ve only just realised that a key part of the AI alignment problem is essentially Wittgenstein’s rule-following argument. (Maybe obvious, but I’ve never seen this stated before.)

His rule-following argument claims that it’s impossible to define a term unambiguously, whether by examples or rules or using other terms; indeed any definition is so ambiguous as to be consistent with any future application of the term. So you can’t even teach someone ‘+’ in such a way that when following your definition/rule/algorithm they will give your desired answer to a sum they haven’t seen before, eg 1000 + 1000 = 2000. They could just as ‘correctly’ give 3000 or -45.7 or pi. (I won’t explain why here.)

Cf no amount of training an AI to be ‘good’ etc will ensure that it remains so in novel situations.

I’m not convinced Wittgenstein was right (and argued against the rule-following argument for my philosophy masters FWIW); maybe a real philosopher more familiar with the topic could apply it usefully to AI alignment.