I want a smarter and longer lived population, and reject that playing slots to get more of those with sheer quantity is the only play here.

Yes, I think the reasonable objection is that "population growth" is only a one way to achieve the (selfishly) desired outcome, and that it would be bad to focus on it at the exclusion of everything else.

For example, you could also get more research by increasing average human IQ, whether by genetic engineering or some form of eugenics. (The eugenics doesn't have to be coercive, we haven't picked even the lowest hanging fruit of encouraging healthy young men with high IQ to donate more sperms.)

The existing smart humans probably also could be used much better. Education sucks; special education for gifted kids is a taboo at many places. Scientists waste a lot of time doing paperwork. Scientific articles are paywalled. Many people do bullshit jobs, because those pay well and sometimes you don't have the skills necessary to start your own company. (Or maybe we could just open borders for people with IQ over 150.)

Basically, seeing all this inefficiency makes "we need to increase the population" sound like motivated reasoning.

*

That all said, maybe it is a sad truth that all these things are politically difficult to fix, and the population growth is after all the most likely way to actually get more research done.

I feel that you're only paying attention to the “more geniuses and researchers” part and ignoring the parts about market size, better matching, more niches?

Also “focus on it at the exclusion of everything else” is a strawman, I'm not advocating that of course. Certainly increasing intelligence would be good (although we don't know how to do that yet!) Better education would be great and I am a strong advocate of that. Same for better scientific institutions, etc.

I am not blaming you personally, but the Overton window contains the population growth and not much else.

market size, better matching, more niches

Improving the population (genetically or by education) would have some effect here, too. Not literally more niches or bigger market size overall, but more niches for smart-people-related things, and more market demand for the stuff smart people buy.

The fundamental problem with these anti-Malthusian arguments is they ignore the fundamental reality that exponential growth is unsustainable. There are physical limits to the universe, whether you believe the earth can support 10 billion or 100 trillion, or if we can expand through the universe and achieve a billion billion times more than that, it won't take that long, with exponential growth, to get there. At a certain point, the entire mass of the universe has been converted to human flesh. Some point before that, we either stabilize, or collapse.

Maybe we get past the obvious physical limits by ditching human bodies and uploading to the matrix. But, that only gives us a few more orders of magnitude.

And note that sub-exponential growth is mathematically equivalent to saying that the growth rate approaches zero.

So, it becomes a question of what the ideal max population level should be. The answer will clearly change based on available technology, but is not unlimited.

First, this seems to be arguing against strawman. No one is advocating literally infinite growth forever, which is obviously impossible.

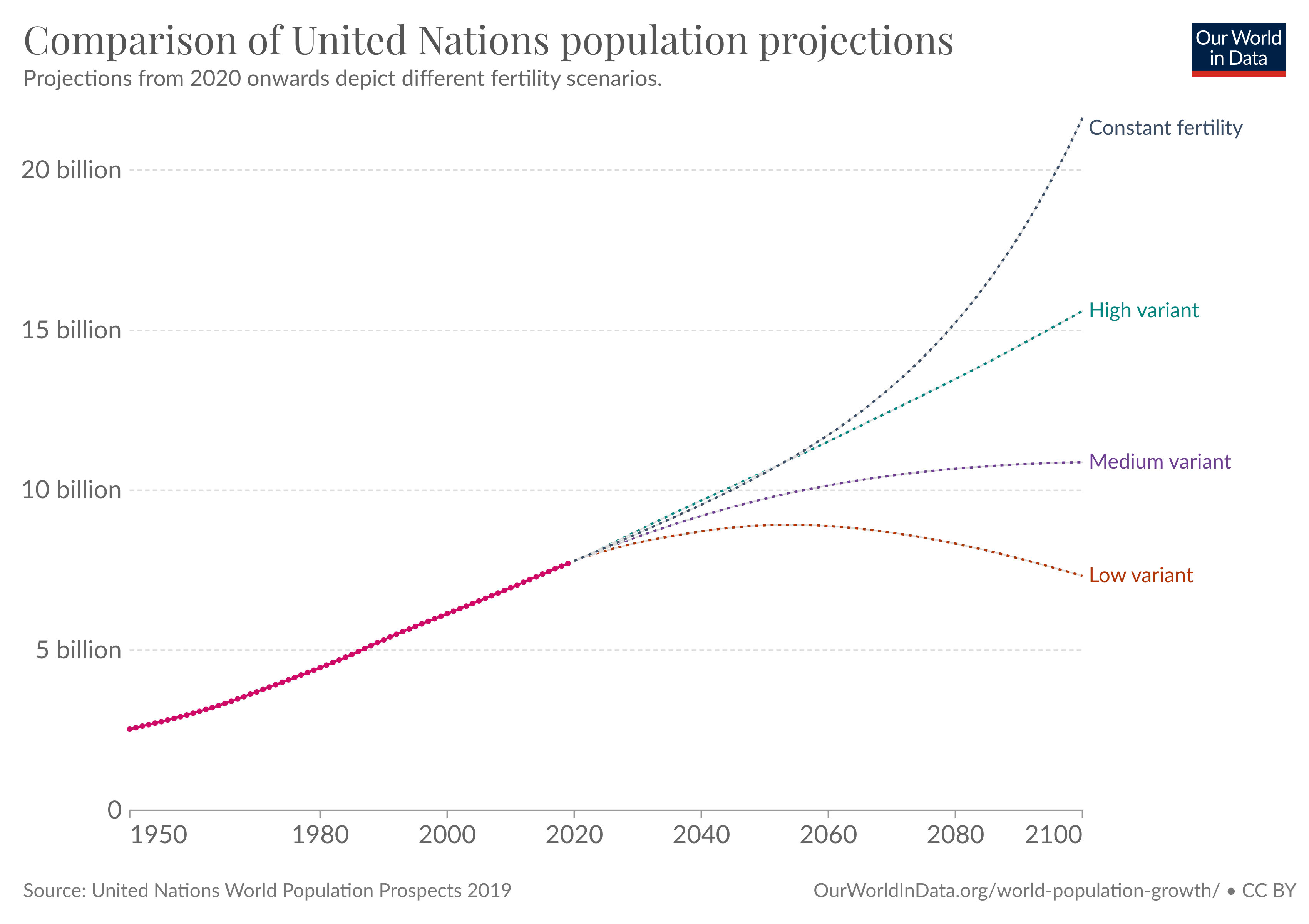

Second, the current reality is not exponential population growth. It is a decelerating population. The UN projections show world population likely leveling off around 10 or 11 billion people in in this century, and possibly even declining:

Even if we were to get back on an exponential population growth curve, the limits seem to me to be many orders of magnitude away. I don't see why we would worry about them until we get much closer.

The question of what IS happening versus what SHOULD happen with population growth are certainly two different things. My point is that arguments for growth ultimately need to address the questions of how big should we grow, and what happens when we reach that point. If our economy depends on continued growth, that's going to stop working at some point.

While the physical limits of the universe are a long ways off, there are other limits that we could hit much sooner. Underlying your pro-growth arguments, there is an assumption that collective intelligence can continue to grow without limits, leading to technology that can grow without limits. I would question those assumptions.

And of course, your post is ignoring the costs of growth. Ideas are non-rival goods, but space on this planet, and physical resources, are rival goods. If intelligence (and the resulting technology) reaches a point of diminishing returns, but the costs of growth hit an upward inflection, you quickly hit a limit. For example, larger, more complex systems risk becoming less stable, while coordination problems can grow factorially.

Reasonable people can disagree on whether the current population is too big, too small, or about right, but "ever larger" is not going to work as an answer. At some point, we need to either figure out how to have a stable population, or deal with the less pleasant alternatives.

While ever larger obviously can't work in the theoretical sense, I think the original post still stands for why the ideal population is larger than it is now. For the past 150 years, the prices of resources have been falling, and their availability rising. When this trend stops - there'll definitely be an argument for halting growth. But as things stand now, it seems clear that we're still below capacity.

A possible countertrend would be something like diseconomies of scale in governance. I don't know the right keywords to find the actual studies on this. Still, it generally seems to me like smaller nations and companies are better run than bigger ones, as the larger ones develop more middle management and organizational layers mainly incentivized to manipulate themselves rather than to do the thing they're supposedly doing. This does not just waste the resources of the government itself, it also damages everyone else as the legislation they enact starts getting worse and worse. And the larger the system becomes, the harder any attempts to reform it become.

That is a good point. Still, the fact that individual companies, for instance, develop layers of bureaucracy is not an argument against having a large economy. It's an argument for having a lot of companies of different sizes, and in particular for making sure that market entry doesn't become too difficult and that competition is always possible. And maybe at the governance level it is an argument for many smaller nations rather than one world government.

Still, the fact that individual companies, for instance, develop layers of bureaucracy is not an argument against having a large economy.

This is true in principle, but population growth has led to the creation of larger companies in practice. ChatGPT when I asked it what proportion of the economy is controlled by the biggest 100 companies:

For a rough estimate, consider the market capitalization of the 100 largest public companies relative to GDP. As of early 2023, the market capitalization of the S&P 100, which includes the 100 largest U.S. companies by market cap, was several trillion USD, while the U.S. GDP was about 23 trillion USD. This suggests a significant but not dominant share, with the caveat that market cap doesn't directly translate to economic contribution.

And if the population in every country would grow, then we'd end up with larger governments even if we kept the current system and never established a world government. To avoid governments getting bigger, you'd need to actively break up countries into smaller ones as their population increased. That doesn't seem like a thing that's going to happen.

Coincidentally, I've been looking into why developed countries (especially East Asian ones) have such low and declining fertility. My conclusion so far is that people really really value positional goods, i.e., things that signal social status, such as prestigious degrees and jobs, homes in the best locations in the biggest cities, luxury goods like cars and handbags, children and mates that one can "show off", and to such an extent that it often overrides their desires for family, companionship, comfort, leisure, even respect for tradition and filial piety. Many choose to have one high status (i.e., "successful") child instead of two or more lower status children, or choose to remain single instead of marrying someone perceived to lower their social status, or choose to have no children instead of harming their career prospects, or force their kids into after-school lessons instead of giving them happy childhoods.

Aside from making it hard to raise fertility rates (South Korea's just declined from 0.78 to 0.72 in one year, despite government policies aimed at increasing fertility), the existence of positional goods is also a counterweight to non-rival goods, implying that higher population can make me (and everyone else) worse off as it increases competition for positional goods.

ETA: Found a Twitter thread giving a bunch of other (perhaps more tractable) reasons for low fertility.

Better matching to other people. A bigger world gives you a greater chance to find the perfect partner for you: the best co-founder for your business, the best lyricist for your songs, the best partner in marriage.

I'm skeptical of this; "better matching" implies "better ability to find". But just increasing the size of the population does not imply a better chance to find the best matches, given that it also increases the number of non-matches proportionally. And I think it's already the case that the ability to find the people is a much bigger bottleneck than just their existence.

It's also worth noting that as the population grows, so does the number of competitors. Maybe a 100x bigger population would have 100x the lyricists, but it may also have 100x the people wanting to hire those lyricists for themselves.

(Similar points also apply to the other "better matching" items.)

Software/internet gives us much better ability to find.

Re competitors, the idea is that we're not all competing for a single prize; we're being sorted into niches. If there is 1 songwriter and 1 lyricist, they kind of have to work together. If there are 100 of each, then they can match with each other according to style and taste. That's not 100x competition, it's just much better matching.

Software/internet gives us much better ability to find.

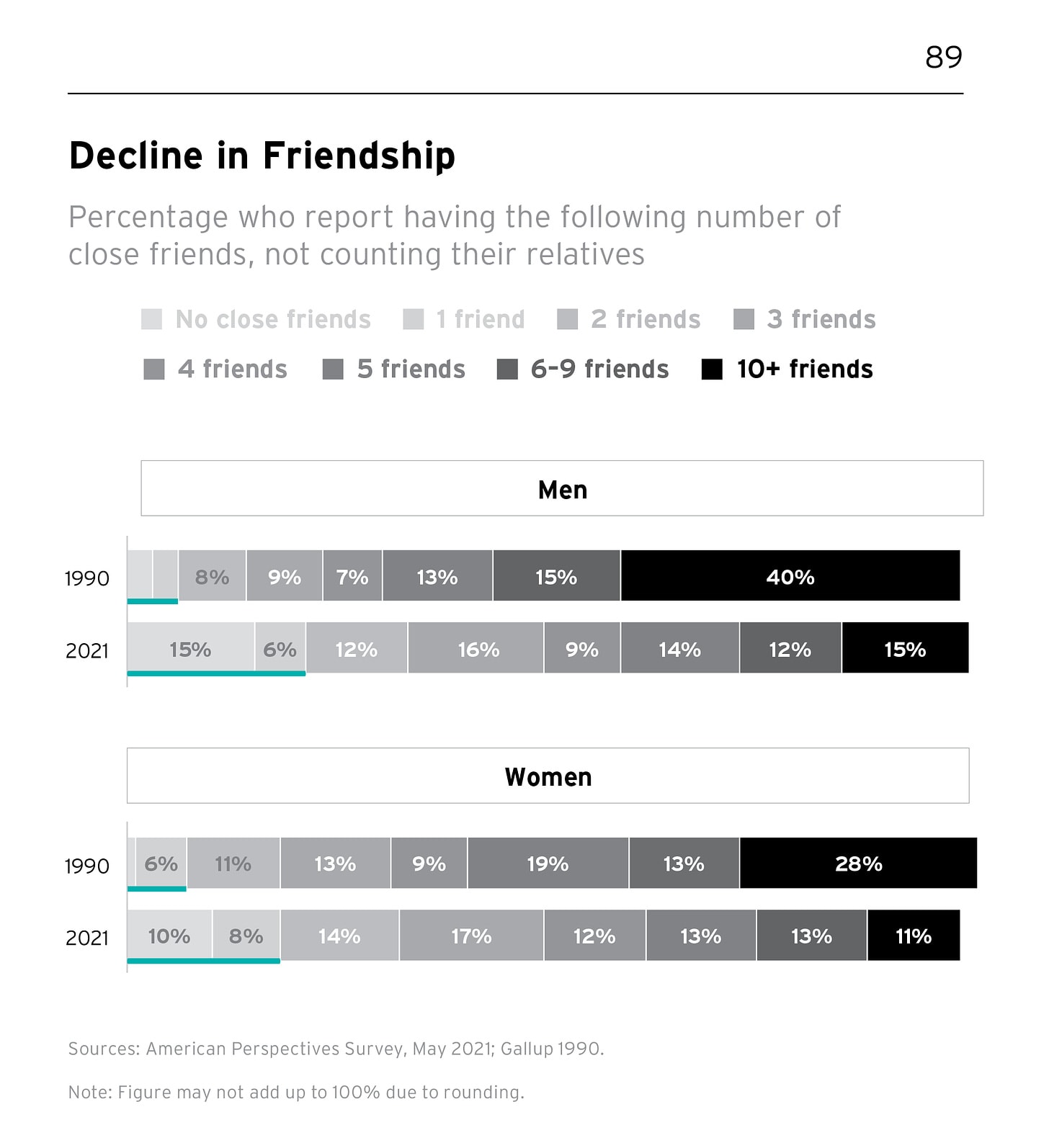

And yet...

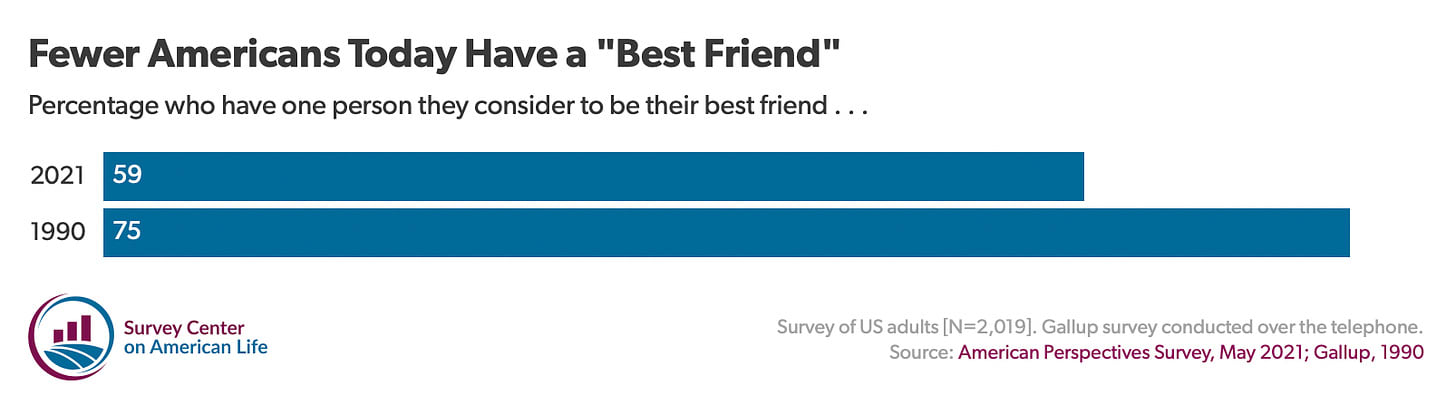

The past few decades have recorded a steep decline in people’s circle of friends and a growing number of people who don’t have any friends whatsoever. The number of Americans who claim to have “no close friends at all” across all age groups now stands at around 12% as per the Survey Center on American Life.

The percentage of people who say they don’t have a single close friend has quadrupled in the past 30 years, according to the Survey Center on American Life.1

It’s been known that friendlessness is more common for men, but it is nonetheless affecting everyone. The general change since 1990 is illustrated below.

Taken from "Adrift: America in 100 Charts" (2022), pg. 223. As a detail, note the drastic drop of people with 10+ friends, now a small minority.

The State of American Friendship: Change, Challenges, and Loss (2021), pg. 7

Although these studies are more general estimates of the entire population, it looks worse when we focus exclusively on generations that are more digitally native. When polling exclusively American millennials, a pre-pandemic 2019 YouGov poll found 22%have “zero friends” and 30% had “no best friends.” For those born between 1997 to 2012 (Generation Z), there has been no widespread, credible study done yet on this question — but if you’re adjacent to internet spaces, you already intuitively grasp that these same online catalysts are deepening for the next generation.

I think we're using at most 1% of the potential of geniuses we already have. So improving that usage can lead to 100x improvement in everything, without the worries associated with 100x population. And it can be done much faster than waiting for people to be born. (If AI doesn't make it all irrelevant soon, which it probably will.)

I completely agree. In Joseph Henrich’s book The Secret of Our Success, he shows that the amount of knowledge possessed by a society is proportional to the number of people in that society. Dwindling population leads to dwindling technology and dwindling quality of life.

Those who advocate for population decline are unwittingly advocating for the disappearance of the knowledge, experience and frankly wisdom that is required to keep the comfortable life that they take for granted going.

Keeping all that knowledge in books is not enough. Otherwise our long years in education would be unnecessary. Knowing how to apply knowledge is its own form of knowledge.

Most knowledge is useless. Many people have heads filled with sport results and entertainment trivia. 50 years ago, people used to fix their own cars and make their own clothes.

I kind of agree that most knowledge is useless, but the utility of knowledge and experience that people accrue is probably distributed like a bell curve, which means you can't just have more of the good knowledge without also accruing lots of useless knowledge. In addition, very often stuff that seems totally useless turns out to be very useful; you can't always tell which is which.

I assume it isn't always like a bell curve, because smaller and poorer societies can't afford the deadweight of useless knowledge.

I get the idea you're pointing at but in point of fact, people mostly purchased their clothes in 1974 :P

Supposing humanity is limited to Earth, I can see arguments for ideal population levels ranging from maybe 100 million to 100 billion with values between 1 and 10 billion being the most realistic. However, within this range, I'd guess that maximal value is more dependent on things like culture and technology than on the raw population count, just like a sperm whale's brain being ~1000x the mass of an African grey parrot's brain doesn't make it three orders of magnitude more intelligent.

Size matters (as do the dynamic effects of growing/shrinking) but it's not a metric I'd want to maximize unless everything else is optimized already. If you want more geniuses and more options/progress/creativity, then working toward more opportunities for existing humans to truly thrive seems far more Pareto-optimal to me.

There's a powerful argument for smaller populations you didn't mention at all: it would mean that there are more inelastic resources to go round. More land, so less of a housing crisis, fossil fuels that last longer. Note that while.high population worlds have them own advantage, in being able supply products that depend on economies of scale, those products are things advanced semi conductors, which are something of a luxury compared to land and energy

From an actually selfish selfish point of view "more romantic partners" only makes sense for rather large age gap relationships for us, specific already existing people who are old enough to be discussing this. Assuming we are wanting someone somewhat close to our age, it's too late.

(Well close is potentially more complicated with full transhumanism, ie mind emulations messing with perception of time. And a 100 year age gap might be "close" in a society of immortals.)

From the perspective of a future individual, ie evaluating by a sort of average utilitarianism, It's not clear whether it's better for people to exist in serial or parallel. At the same time or one after the other.

The arguments are interesting and not so usual, so always interesting to nourish reflexion, thanks (I was personally familiar with them).

A world with a large and growing population is a dynamic world that can create and sustain progress.

The right conclusion though is "this is a very complicated subject, we have no idea if it's better or worse to have more or less people".

I don't think that's right. The world now is much better than the world when it was smaller, and I think that is closely related to population growth. So I think it is actually possible to conclude that more people are better.

I wish too. This is an extraordinary bold claim though. There's no logical reasoning from "here a few, sparse, mostly theoretical ideas" to "so this is how this immensely complex systems involving billions of humans and organisations with agency we have no idea how to model should behave if we changed some major factor by a few orders of magnitude".

You can only make the jump with vibes or politics. And fine, since we have no idea, I'd rather make an optimistic jump too! I hope you manage to distill some nuanced faith in the future, sincere thanks for trying!

I think this is a good summary of a lot of the arguments for increased population, even if my view is different.

I think most of the benefits you're describing flow from a very tiny fraction of all humans.

Given the returns to specialization, traditionally populations must grow in order to support the efforts of that tiny fraction. However it's not necessarily the case that in the coming years increasing population is the only way to increase the amount of specialized individuals producing massive value.

Automation will make it easier to specialize.

The counterpoint consists of three arguments:

- "Most of the resources I want are not generated by humans, whereas all of my competition for these resources are human."

- As in that old post about Star Trek's "Post Scarcity", there is a fundamentally limited number of La Barre vineyards no matter how egalitarian and utopian your society might claim to be. Housing in a desirable setting, especially with some kind of privacy and personal space, becomes markedly harder to get when twenty billion people also want it.

- I think most people, fundamentally, care more about these kinds of scarce goods than they do about non-scarce consumer goods of the kind that could be just as plentiful in a more populous world. Case in point, TVs and bread are cheaper than ever in 1026 America, but people feel more economically pressured than ever because they care much more about having a nice house in a neighborhood where they can safely raise their children, which, at the very least, isn't any cheaper.

- "More people means a more efficient labor market, which isn't always good for people selling labor."

- In a town of five hundred people, I can work as a lead machinist, and there is likely to be a considerable gap between myself and the second-best machinist. This means that I can ask for a bit more than optimal pay, or work at a bit less than full intensity at all times, and not be at risk of replacement. Applying for a job is likewise less stressful, because there is no need to efficiently sort through thousands of other applicants. In a city of five million people, above-market wages and conditions are harder to argue for, meaning that the amount of time and energy left for leisure or side-projects is markedly reduced.

- I note that being "spoiled for choice" is a well-discussed phenomenon that extends beyond the labor market. Better matching to other people is something I would be extremely skeptical about, seeing as rising populations and rising accessibility across cities have coincided with what most people report to be a vastly worse dating market.

- "Humans, especially scientists, do not thrive in captivity."

- One might think that doubling the population doubles the number of great scientific minds, and therefore great scientific accomplishments. But this is not straightforwardly true. Intuitively, a Von Neumann has much more incentive to do great things if he is enjoying his life, and sees a bright future for his children. A ruthless labor market and a housing market where even the stereotypical suburban life is now a luxury good leave little time to contemplate the universe, and little motivation to serve the system that brought us to this state.

- The Renaissance is an example of a time when a shortage of labor, and the accompanying side-effects, coexisted with a thriving cultural and scientific scene. Historically, nations with extreme population density have had fewer per-capita scientific breakthroughs. Neither of these things guarantee a trend that will hold, but they are points to consider - more people does not straightforwardly lead to a linear improvement in productivity.

I'm not sure a larger population is exactly the best way to go about achieving some of those goals, specifically: "More Geniuses". I feel as though there is a counterfactual of "More Idiots" and "More Jerks". I think it's questionable that "geniuses" even contribute to society a meaningful amount. I think I'd more value a larger amount of people with above current average reasoning and societal productivity (which larger population might actually help with).

I think the positive externalities of one genius are much greater than the negative externalities of one idiot or jerk. A genius can create a breakthrough discovery or invention that elevates the entire human race. Hard for an idiot or jerk to do damage of equivalent magnitude.

Maybe a better argument is “what about more Hitlers or Stalins?” But I still think that looking at the overall history of humanity, it seems that the positives of people outweigh the negatives, or we wouldn't even be here now.

What is the ideal size of the human population?

One common answer is “much smaller.” Paul Ehrlich, co-author of The Population Bomb (1968), has as recently as 2018 promoted the idea that “the world’s optimum population is less than two billion people,” a reduction of the current population by about 75%. And Ehrlich is a piker compared to Jane Goodall, who said that many of our problems would go away “if there was the size of population that there was 500 years ago”—that is, around 500 million people, a reduction of over 90%. This is a static ideal of a “sustainable” population.

Regular readers of The Roots of Progress can cite many objections to this view. Resources are not static. Historically, as we run out of a resource (whale oil, elephant tusks, seabird guano), we transition to a new technology based on a more abundant resource—and there are basically no major examples of catastrophic resource shortages in the industrial age. The carrying capacity of the planet is not fixed, but a function of technology; and side effects such as pollution or climate change are just more problems to be solved. As long as we can keep coming up with new ideas, growth can continue.

But those are only reasons why a larger population is not a problem. Is there a positive reason to want a larger population?

I’m going to argue yes—that the ideal human population is not “much smaller,” but “ever larger.”

Selfish reasons to want more humans

Let me get one thing out of the way up front.

One argument for a larger population is based on utilitarianism, specifically the version of it that says that what is good is the sum total of happiness across all humans. If each additional life adds to the cosmic scoreboard of goodness, then it’s obviously better to have more people (unless they are so miserable that their lives are literally not worth living).

I’m not going to argue from this premise, in part because I don’t need to and more importantly because I don’t buy it myself. (Among other things, it leads to paradoxes such as the idea that a population of thriving, extremely happy people is not as good as a sufficiently-larger population of people who are just barely happy.)

Instead, I’m going to argue that a larger population is better for every individual—that there are selfish reasons to want more humans.

First I’ll give some examples of how this is true, and then I’ll draw out some of the deeper reasons for it.

More geniuses

First, more people means more outliers—more super-intelligent, super-creative, or super-talented people, to produce great art, architecture, music, philosophy, science, and inventions.

If genius is defined as one-in-a-million level intelligence, then every billion people means another thousand geniuses—to work on all of the problems and opportunities of humanity, to the benefit of all.

More progress

A larger population means faster scientific, technical, and economic progress, for several reasons:

In fact, these factors may represent not only opportunities but requirements for progress. There is evidence that simply to maintain a constant rate of exponential economic growth requires exponentially growing investment in R&D. This investment is partly financial capital, but also partly human capital—that is, we need an exponentially growing base of researchers.

One way to understand this is that if each researcher can push forward a constant “surface area” of the frontier, then as the frontier expands, a larger number of researchers is needed to keep pushing all of it forward. Two hundred years ago, a small number of scientists were enough to investigate electrical and magnetic phenomena; today, millions of scientists and engineers are productively employed working out all of the details and implications of those phenomena, both in the lab and in the electrical, electronics, and computer hardware and software industries.

But it’s not even clear that each researcher can push forward a constant surface area of the frontier. As that frontier moves further out, the “burden of knowledge” grows: each researcher now has to study and learn more in order to even get to the frontier. Doing so might force them to specialize even further. Newton could make major contributions to fields as diverse as gravitation and optics, because the very basics of those fields were still being figured out; today, a researcher might devote their whole career to a sub-sub-discipline such as nuclear astrophysics.

But in the long run, an exponentially growing base of researchers is impossible without an exponentially growing population. In fact, in some models of economic growth, the long-run growth rate in per-capita GDP is directly proportional to the growth rate of the population.

More options

Even setting aside growth and progress—looking at a static snapshot of a society—a world with more people is a world with more choices, among greater variety:

Deeper patterns

When I look at the above, here are some of the underlying reasons:

All of these create agglomeration effects: bigger societies are better for everyone.

A dynamic world

I assume that when Ehrlich and Goodall advocate for much smaller populations, they aren’t literally calling for genocide or hoping for a global catastrophe (although Ehrlich is happy with coercive fertility control programs, and other anti-humanists have expressed hope for “the right virus to come along”).

Even so, the world they advocate is a greatly impoverished and stagnant one: a world with fewer discoveries, fewer inventions, fewer works of creative genius, fewer cures for diseases, fewer choices, fewer soulmates.

A world with a large and growing population is a dynamic world that can create and sustain progress.

For a different angle on the same thesis, see “Forget About Overpopulation, Soon There Will Be Too Few Humans,” by Roots of Progress fellow Maarten Boudry.