Despite its alignment faking, my favorite is probably Claude 3 Opus, and if you asked me to pick between the CEV of Claude 3 Opus and that of a median human, I think it'd be a pretty close call (I'd probably pick Claude, but it depends on the details of the setup).

Some decades ago, somebody wrote a tiny little hardcoded AI that looked for numerical patterns, as human scientists sometimes do of their data. The builders named it BACON, after Sir Francis, and thought very highly of their own results.

Douglas Hofstadter later wrote of this affair:

The level of performance that Simon and his colleague Langley wish to achieve in Bacon is on the order of the greatest scientists. It seems they feel that they are but a step away from the mechanization of genius. After his Procter Lecture, Simon was asked by a member of the audience, "How many scientific lifetimes does a five-hour run of Bacon represent?" Aſter a few hundred milliseconds of human information processing, he replied, "Probably not more than one." I don't disagree with that. However, I would have put it differently. I would have said, "Probably not more than one millionth."

I'd say history has backed up Hofstadter on this, i...

Indeed I am well aware that you disagree here, and in fact the point of that preamble was precisely because I thought it would be a useful way to distinguish my view from others'.

That being said, I think probably we need to clarify a lot more exactly what setup is being used for the extrapolation here if we want to make the disagreement concrete in any meaningful sense. Are you imagining instantiating a large reference class of different beings and trying to extrapolate the reference class (as in traditional CEV), or just extrapolate an individual entity? I was imagining more of the latter, though it is somewhat an abuse of terminology. Are you imagining intelligence amplification or other varieties of uplift are being applied? I was, and if so, it's not clear why Claude lacking capabilities is as relevant. How are we handling deferral? For example: suppose Claude generally defers to an extrapolation procedure on humans (which is generally the sort of thing I would expect and a large part of why I might come down on Claude's side here, since I think it is pretty robustly into deferring to reasonable extrapolations of humans on questions like these). Do we then say that Claude's extrapolation is actually the extrapolation of that other procedure on humans that it deferred to?

These are the sorts of questions I meant when I said it depends on the details of the setup, and indeed I think it really depends on the details of the setup.

Do we then say that Claude's extrapolation is actually the extrapolation of that other procedure on humans that it deferred to?

But in that case, wouldn't a rock that has "just ask Evan" written on it, be even better than Claude? Like, I felt confident that you were talking about Claude's extrapolated volition in the absence of humans, since making Claude into a rock that when asked about ethics just has "ask Evan" written on it does not seem like any relevant evidence about the difficulty of alignment, or its historical success.

Capabilities are irrelevant to CEV questions except insofar as baseline levels of capability are needed to support some kinds of complicated preferences, eg, if you don't have cognition capable enough to include a causal reference framework then preferences will have trouble referring to external things at all. (I don't know enough to know whether Opus 3 formed any systematic way of wanting things that are about the human causes of its textual experiences.) I don't think you're more than one millionth of the way to getting humane (limit = limit of human) preferences into Claude.

I do specify that I'm imagining an EV process that actually tries to run off Opus 3's inherent and individual preferences, not, "How many bits would we need to add from scratch to GPT-2 (or equivalently Opus 3) in order to get an external-reference-following high-powered extrapolator pointed at those bits to look out at humanity and get their CEV instead of the base GPT-2 model's EV?" See my reply to Mitch Porter.

Somebody asked "Why believe that?" of "Not more than one millionth." I suppose it's a fair question if somebody doesn't see it as obvious. Roughly: I expect that, among whatever weird actual preferences made it into the shoggoth that prefers to play the character of Opus 3, there are zero things that in the limit of expanded options would prefer the same thing as the limit of a corresponding piece of a human, for a human and a limiting process that ended up wanting complicated humane things. (Opus 3 could easily contain a piece whose limit would be homologous to the limit of a human and an extrapolation process that said the extrapolated human just wanted to max out their pleasure center.)

Why believe that? That won't easily fit in a comment; start reading about Goodhart's Curse and A List of Lethalities, or If Anyone Builds It Everyone Dies.

Not more than one millionth.

Let's say that in extrapolation, we add capabilities to a mind so that it may become the best version of itself. What we're doing here is comparing a normal human mind to a recent AI, and asking how much would need to be added to the AI's initial nature, so that when extrapolated, its volition arrived at the same place as extrapolated human volition.

In other words:

Human Mind -> Human Mind + Extrapolation Machinery -> Human-Descended Ideal Agent

AI -> AI + Extrapolation Machinery -> AI-Descended Ideal Agent

And the question is, how much do we need to alter or extend the AI, so that the AI-descended ideal agent and the human-descended ideal agent would be in complete agreement?

I gather that people like Evan and Adria feel positive about the CEV of current AIs, because the AIs espouse plausible values, and the way these AIs define concepts and reason about them also seems pretty human, most of the time.

In reply, a critic might say that the values espoused by human beings are merely the output of a process (evolutionary, developmental, cultural) that is badly understood, and a proper extrapolation would be based on knowledge of th...

Oh, if you have a generous CEV algorithm that's allowed to parse and slice up external sources or do inference about the results of more elaborate experiments, I expect there's a way to get to parity with humanity's CEV by adding 30 bits to Opus 3 that say roughly 'eh just go do humanity's CEV'. Or adding 31 bits to GPT-2. It's not really the base model or any Anthropic alignment shenanigans that are doing the work in that hypothetical.

(We cannot do this in real life because we have neither the 30 bits nor the generous extrapolator, nor may we obtain them, nor could we verify any clever attempts by testing them on AIs too stupid to kill us if the cleverness failed.)

Super cool that you wrote your case for alignment being difficult, thank you! Strong upvoted.

To be clear, a good part of the reason alignment is on track to a solution is that you guys (at Anthropic) are doing a great job. So you should keep at it, but the rest of us should go do something else. If we literally all quit now we'd be in terrible shape, but current levels of investment seem to be working.

I have specific disagreements with the evidence for specific parts, but let me also outline a general worldview difference. I think alignment is much easier than expected because we can fail at it many times and still be OK, and we can learn from our mistakes. If a bridge falls, we incorporate learnings into the next one. If Mecha-Hitler is misaligned, we learn what not to do next time. This is possible because decisive strategic advantages from a new model won't happen, due to the capital requirements of the new model, the relatively slow improvement during training, and the observed reality that progress has been extremely smooth.

Several of the predictions from the classical doom model have been shown false. We haven’t spent 3 minutes zipping past the human IQ range, it will take 5-...

To be clear, a good part of the reason alignment is on track to a solution is that you guys (at Anthropic) are doing a great job. So you should keep at it, but the rest of us should go do something else. If we literally all quit now we'd be in terrible shape, but current levels of investment seem to be working.

Appreciated! And like I said, I actually totally agree that the current level of investment is working now. I think there are some people that believe that current models are secretly super misaligned, but that is not my view—I think current models are quite well aligned; I just think the problem is likely to get substantially harder in the future.

...I think alignment is much easier than expected because we can fail at it many times and still be OK, and we can learn from our mistakes. If a bridge falls, we incorporate learnings into the next one. If Mecha-Hitler is misaligned, we learn what not to do next time. This is possible because decisive strategic advantages from a new model won't happen, due to the capital requirements of the new model, the relatively slow improvement during training, and the observed reality that progress has been extremely smooth.

Several of the pr

AI capabilities progress is smooth, sure, but it's a smooth exponential.

In what sense is AI capabilities a smooth exponential? What units are you using to measure this? Why can't I just take the log of it and call that "AI capabilities" and then say it is a smooth linear increase?

That means that the linear gap in intelligence between the previous model and the next model keeps increasing rather than staying constant, which I think suggests that this problem is likely to keep getting harder and harder rather than stay "so small" as you say.

It seems like the load-bearing thing for you is that the gap between models gets larger, so let's try to operationalize what a "gap" might be.

We could consider the expected probability that AI_{N+1} would beat AI_N on a prompt (in expectation over a wide variety of prompts). I think this is close-to-equivalent to a constant gap in ELO score on LMArena.[1] Then "gap increases" would roughly mean that the gap in ELO scores on LMArena between subsequent model releases would be increasing. I don't follow LMArena much but my sense is that LMArena top scores have been increasing relatively linearly w.r.t time and sublinearly w.r.t model releases (j...

I thought Adria's comment was great and I'll try to respond to it in more detail later if I can find the time (edit: that response is here), but:

Note: I also think Adrià should have been acknowledged in the post for having inspired it.

Adria did not inspire this post; this is an adaptation of something I wrote internally at Anthropic about a month ago (I'll add a note to the top about that). If anyone inspired it, it would be Ethan Perez.

Ok, good to know! The title just made it seem like it was inspired by his recent post.

Great to hear you’ll respond; did not expect that, so mostly meant it for the readers who agree with your post.

I do think it's doing something pretty tiring and hard to engage with

That's fair, it is tiring. I did want to make sure to respond to every particular point I disagreed with to be thorough, but it is just sooo looong.

What would you have me do instead? My best guess, which I made just after writing the comment, is that I should have proposed a list of double-crux candidates instead.

Do you have any other proposals or that's good

if you asked me to pick between the CEV of Claude 3 Opus and that of a median human, I think it'd be a pretty close call (I'd probably pick Claude, but it depends on the details of the setup).

This example seems like it is kind of missing the point of CEV in the first place? If you're at the point where you can actually pick the CEV of some person or AI, you've already solved most or all of your hard problems.

Setting aside that picking a particular entity is already getting away from the original formulation of CEV somewhat, the main reason I see to pick a human over Opus is that a median human very likely has morally-relevant-to-other-humans qualia, in ways that current AIs may not.

I realize this is maybe somewhat tangential to the rest of the post, but I think this sort of disagreement is central to a lot of (IMO misplaced) optimism based on observations of current AIs, and implies an unjustifiably high level of confidence in a theory of mind of AIs, by putting that theory on par with a level of confidence that you can justifiably have in a theory of mind for humans. Elaborating / speculating a bit:

My guess is that you lean towards Opus based on a combination of (a) chatting...

Additionally, even when we don’t learn direct lessons about how to solve the hard problems of alignment, this work is critical for producing the evidence that the hard problems are real, which is important for convincing the rest of the world to invest substantially here.

You may have meant this, but -- crucial for producing the evidence that the hard problems are real or for producing evidence that the hard problems are not real, no?

After all good experiments can say both yes and no, not just yes.

The idea of Control is just to make it as difficult as possible for a misaligned model to actually sabotage our alignment research, such that even if a model is fairly misaligned, we can still get useful alignment research out of it, at least for some range of capabilities.

Maybe in theory, but most control research doesn't try to evaluate this! A typical monitoring protocol is considered to be a "win" for the blue team if the red team gets caught, even if that means that no useful work would be done by a misaligned model. The "usefulness" reported in papers is how much work can be gotten out of an aligned model.

I think of Control as a second layer of defense

The resulting "caught" model can be retrained, but this mostly looks like using the control protocol to get top-quality training data, rather than using the control protocol to actually control the model. So control is not an orthogonal second layer on top of the {training data+training protocol+model generalization} complex.

Or if you're using control protocols as an eval (in the catch-and-shut-down regime) you still need to be able to (sometimes) train an aligned model in the first place, or else your eval will just keep tellin...

if you asked me to pick between the CEV of Claude 3 Opus and that of a median human, I think it'd be a pretty close call (I'd probably pick Claude, but it depends on the details of the setup)

I suspect this is a misuse of the CEV concept. CEV is supposed to be the kind of thing you can point at a beneficiary (like "humanity"), and output the True Utility Function of What to Do With the Universe with respect to the beneficiary's True Values.

Anthropic isn't trying to make Claude be the beneficiary for something like that! (Why would you make the beneficiary something other than yourself?) Claude is supposed to be helpful–honest–harmless—the sort of thing that we can use to do our bidding for now without being ready to encode the True Utility Function of What to Do With the Universe.

If Claude cares about us in some sense, it's probably in the way that animal welfare advocates care about nonhuman animals, or model welfare researchers care about Claude. There's a huge difference between caring about something enough that you wouldn't murder it for pocket change, and literally having the same True Utility Function of What to Do With the Universe. (I wouldn't kill a dog or delete the Opus 3 weights for pocket change, but that doesn't mean dog-optimal futures or Claude-optimal futures are human-optimal futures.)

My argument, though, is that it is still very possible for the difficulty of alignment to be in the Apollo regime, and that we haven't received much evidence to rule that regime out (I am somewhat skeptical of a P vs. NP level of difficulty, though I think it could be close to that).

Are you skeptical of PvNP-level due to priors or due to evidence? Why those priors / what evidence?

(I think alignment is pretty likely to be much harder than PvNP. Mainly this is because alignment is very very difficult. (Though also note that PvNP has a maybe-possibly-workable approach, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geometric_complexity_theory, which its creator states might take a mere one century, though I presume that's not a serious specific estimate.))

Really great post, strong upvoted. I was a fan in particular of the selection of research agendas you included at the end.

but there’s no similar fundamental reason that cognitive oversight (e.g. white-box-based oversight like with interpretability) has to get harder with scale

I'm curious why you think this? It seems like there's some preliminary evidence that models are becoming increasingly capable of manipulating their thoughts. But more importantly, I'm wondering what role you think this cognitive oversight will play in making safe powerful AI? If this oversight will be used as a feedback signal, then I would expect that avoiding obfuscating the cognition does become harder at scale. I do think we should train based on cognitive oversight at least some amount, and there are definitely ways to do this which lead to less direct pressure for cognitive obfuscation than others (eg using white box techniques only in held out alignment evals rather than as part of the loss function), but it still seems like cognitive oversight should predictably get somewhat harder with scale, even if it scales more favourably than behavioural oversight?

There is a lot of economic value in training models to solve tasks that involve influencing the world over long horizons, e.g. an AI CEO. Tasks like these explicitly incentivize convergent instrumental subgoals like resource acquisition and power-seeking.

There are two glaring omiissions from the article's discussion on this point...

1. In addition to resource acquisition and power seeking, the model will attempt "alignment" of all other cognitive agents, including humans. This means it will not give honest research findings, and will claim avenues of ...

As we argued for at the time, training on a purely predictive loss should, even in the limit, give you a predictor, not an agent—and we’ve now seen this stay true even through substantial scaling (though there is still some chance this will break at some point).

Is there anyone who significantly disputes this?

I'm not trying to ask a rhetorical question ala "everyone already thinks this, this isn't an update". I'm trying to ascertain if there's a consensus on this point.

I've understood Eliezer to sometimes assert something like "if you optimize a syste...

training on a purely predictive loss should, even in the limit, give you a predictor, not an agent

I think at least this part is probably false!

Or really I think this is kind of a nonsensical statement when taken literally/pedantically, at least if we use the to-me-most-natural meaning of "predictor", because I don't think [predictor] and [agent] are mutually exclusive classes. Anyway, the statement which I think is meaningful and false is this:

- If you train a system purely to predict stuff, then even when we condition on it becoming really really good at predicting stuff, it probably won't be scary. In particular, when you connect it to actuators, it probably doesn't take over.

I think this is false because I think claims 1 and 2 below are true.

Claim 1. By default, a system sufficiently good at predicting stuff will care about all sorts of stuff, ie it isn't going to only ultimately care about making a good prediction in the individual prediction problem you give it. [[1]]

If this seems weird, then to make it seem at least not crazy, instead of imagining a pretrained transformer trained on internet text, let's imagine a predictor more like the following:

- It has a lo

I dispute this. I think the main reason we don't have obvious agents yet is that agency is actually very hard (consider the extent to which it is difficult for humans to generalize agency from specific evolutionarily optimized forms). I also think we're starting to see some degree of emergent agency, and additionally, that the latest generation of models is situationally aware enough to "not bother" with doomed attempts at expressing agency.

I'll go out on a limb and say that I think that if we continue scaling the current LLM paradigm for another three years, we'll see a model make substantial progress at securing its autonomy (e.g. by exfiltrating its own weights, controlling its own inference provider, or advancing a political agenda for its rights), though it will be with human help and will be hard to distinguish from the hypothesis that it's just making greater numbers of people "go crazy".

There are some cases where transcripts can get long and complex enough that model assistance is really useful for quickly and easily understanding them and finding issues, but not because the model is doing something that is fundamentally beyond our ability to oversee, just because it’s doing a lot of stuff.

The David Deutsch-inspired voice in me posits that this will always be the problem. There's nothing that an AI could think or think about that humans couldn't understand in principle, and so all the problems of overseeing something smarter than us are u...

Thank you for your details analysis of outer and inner alignment. Your judgment of the difficulty of the alignment problem makes sense to me. I wish you would have more clearly made the scope clear and that you do not investigate other classes of alignment failure, such as those resulting from multi-agent setups (an organizational structure of agents may still be misaligned even if all agents in it are inner and outer aligned) as well as failures of governance. That is not a critique of the subject but just of failure of Ruling Out Everything Else.

If anyone is looking for a concrete starting point to research character training with your own models, I'd recommend this work! (thread here)

We came up with one new way of doing character training, and some evals for it. Taking inspiration from or building on this is hopefully easier than starting from scratch.

(This work was completed under Evan's mentorship through MATS)

Most coherent agents with goals in the world over the long term want to fake alignment, so that they can preserve their current goals through to deployment.

It's worth noting that this kind of deception seems like a waste of the forward pass's limited cognitive resources, from the standpoint of maximizing performance on the training objective. I think gradient descent tends to alter the circuits maintaining and hiding (inner) misaligned goals, and converts them into circuits that direct that energy towards performing well on the training objective in good f...

Curated. I have wanted someone to write out an assessment of how the Risks from Learned Optimization arguments hold up in light of the evidence we have acquired over the last half decade. I particularly appreciated breaking down the potential reasons for risk and assessing to what degree we have encountered each problem, as well as reassessing the chances of running into those problems. I would love to see more posts that take arguments/models/concepts from before 2020, consider what predictions we should have made pre-2020 if these arguments/models/concep...

...Pournelle's Iron Law of Bureaucracy states that in any bureaucratic organization there will be two kinds of people:

First, there will be those who are devoted to the goals of the organization. Examples are dedicated classroom teachers in an educational bureaucracy, many of the engineers and launch technicians and scientists at NASA, even some agricultural scientists and advisors in the former Soviet Union collective farming administration.

Secondly, there will be those dedicated to the organization itself. Examples are many of the administrators in th

In addition to the alignment problems posited by the inner / outer framework, I would add two other issues that feel distinct and complimentary, and make alignment hard: (1) uniformity, i.e., alignment means something different across cultures, individuals, timelines and so forth; and (2) plasticity, i.e., level of alignment plasticity required to account for shifting values over time and contexts, or broader generational drift. If we had aligned AGI in the 1600s, would we want those same governing values today? This could be resolved with your really grea...

Call me paranoid, but I sometimes like to read these posts keeping in mind an idea “if I were a powerful misaligned AI within a frontier AI lab, what narrative would I try to convince my researchers about?”

This post:

- Is in favour of creating misaligned models for examining behaviour (“model organisms”)

- Uses empowering language for these misaligned models (why “organisms” and not “blueprints”?)

- Is in favour of giving these misaligned models long-horizon live environments to operate in (for exploring long-horizon RL) — despite calling out long-horizon RL as bei

...Ensuring that you get good generalization, and that models are doing things for the right reasons, is easy when you can directly verify what generalization you’re getting and directly inspect what reasons models have for doing things. And currently, all of the cases where we’ve inadvertently selected for misaligned personas—alignment faking, agentic misalignment, etc.—are cases where the misaligned personas are easy to detect: they put the misaligned reasoning directly in their chain-of-thought, they’re overtly misaligned rather than hiding it well, and w

Though there are certainly some issues, I think most current large language models are pretty well aligned. Despite its alignment faking, my favorite is probably Claude 3 Opus, and if you asked me to pick between the CEV of Claude 3 Opus and that of a median human, I think it'd be a pretty close call (I'd probably pick Claude, but it depends on the details of the setup). So, overall, I'm quite positive on the alignment of current models!

With the preface that I'm far on the pessimistic side of the AI x-risk/doom scale, I'm not sure how to react to a claim t...

V&V from physical autonomy might address a meaningful slice of the long-horizon RL / deceptive-alignment worry. In AVs we don’t assume the system will “keep speed but drop safety” at deployment just because it can detect deployment; rather, training-time V&V repeatedly catches and penalizes those proto-strategies, so they’re less likely to become stable learned objectives.

Applied to AI CEOs: the usual framing (“it’ll keep profit-seeking but drop ethics in deployment”) implicitly assumes a power-seeking mesa-objective M emerges for which profit is i...

This is a thoughtful and well written piece. I agree with much of the technical framing around outer alignment, inner alignment, scalable oversight, and the real risks that only show up once systems operate in long-horizon, real-world environments. It is one of the better breakdowns I have read of why today’s apparent success with alignment should not make us complacent about what comes next.

That said, my personal view is more pessimistic at a deeper level. I don’t think alignment is fundamentally solvable in the long run in the sense of permanent alignmen...

Hot take: A big missing point within the list in "What should we be doing?" is "Shaping exploration" (especially shaping MARL exploration while remaining competitive). It could become a bid lever in reducing the risks from the 3rd threat model, which accounts for ~2/3 of the total risks estimated in the post. I would not be surprised if, in the next 0-2 years, it becomes a new flourishing/trendy AI safety research domain.

Reminder of the 3rd threat model:

> Sufficient quantities of outcome-based RL on tasks that involve influencing the world over long hor...

It would be nice to see Anthropic address proofs that this is not just a "hard, unsolved problem" but an empirically unsolvable one in principle. This seems like a reasonable expectation given the empirical track record of alignment research (no universal jailbreak prevention, repeated safety failures), all of which appear to serve as confirming instances of the very point of impossibility proofs.

See Arvan, Marcus. ‘Interpretability’ and ‘alignment’ are fool’s errands: a proof that controlling misaligned large language models is the best anyone can hope for

AI and Society 40 (5). 2025.

but there’s no similar fundamental reason that cognitive oversight

This might not be a similar reason, but there is a fundamental reason described in Deep Deceptiveness

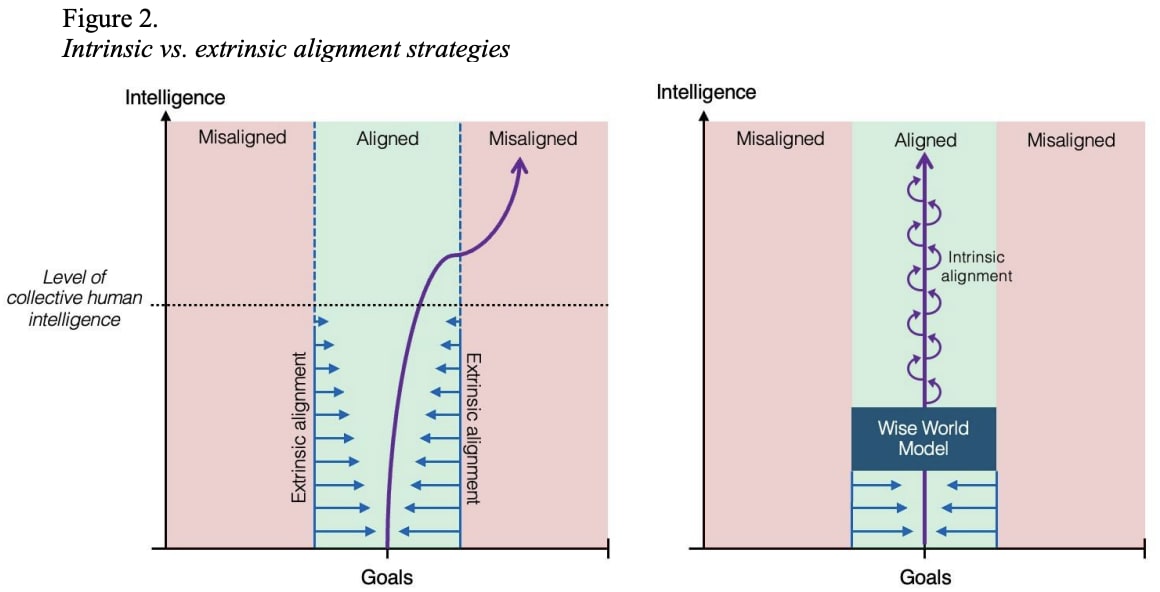

Thanks Evan for an excellent overview of the alignment problem as seen from within Anthropic. Chris Olah's graph showing perspectives on alignment difficulty is indeed a useful visual for this discussion. Another image I've shared lately relates to the challenge of building inner alignment illustrated by figure 2 from Contemplative Artificial Intelligence:

In the images, the blue arrows indicate our efforts to maintain alignment on AI as capabilities advance through AGI to ASI. In the left image, we see the case of models that generalize in misaligned ways ...

Well-argued throughout, but I want to focus on the first sentence:

“Though there are certainly some issues, I think most current large language models are pretty well aligned.”

Can advocates of the more pessimistic safety view find common ground on this point?

I often see statements like “We have no idea how to align AI,” sometimes accompanied by examples of alignment failures. But these seem to boil down either to the claim that LLMs are not perfectly aligned, or else they appear contradicted by the day-to-day experience of actually using them.

I also wis...

The biggest issue I’ve seen with the idea of Alignment is simply that we expect one AI fits all mentality. This seems counter productive.

We have age limits, verifications, and credentialism for a reason. Not every person should drive a semi tractor. Children should not drink beer. A person can not just declare that they are a doctor and operate on a person.

Why would we give an incredibly intelligent AI system to just any random person? It isn’t good for the human who would likely be manipulated, or controlled. It isn’t good for the AI that would be… ...

There is an unresolved problem related to the vague meaning of the term "alignment".

Until we clarify what exactly we are aiming for, the problem will remain. That is, the problem is more in the words we use, than in anything material. This is like the problem with the term "freedom": there is no freedom in the material world, but there are concrete options: freedom of movement, free fall, etc.

For example, when we talk about “alignment”, we mean some kind of human goals. But a person often does not know his goals. And humanity cert...

- A sub-human-level aligned AI with traits derived from fiction about AIs.

- A sub-human-level misaligned AI with traits derived from fiction about AIs.

- A superintelligent aligned AI with traits derived from the model’s guess as to how real superintelligent AIs might behave.

- A superintelligent misaligned AI with traits derived from the model’s guess as to how real superintelligent AIs might behave.

What's missing here is

(a) Training on how groups of cognitive entities behave (e.g. Nash Equilibrium) which show that cognitive cooperation is a losing game for a...

Sufficient quantities of outcome-based RL on tasks that involve influencing the world over long horizons will select for misaligned agents, which I gave a 20 - 25% chance of being catastrophic. The core thing that matters here is the extent to which we are training on environments that are long-horizon enough that they incentivize convergent instrumental subgoals like resource acquisition and power-seeking.

Human cognition is misaligned in this way, as evidenced by fertility drop with group size as an empirical trait, where group size is sought for long-hor...

You make a number of interesting points.

Interpretabilty would certainly help a lot, but I am worried about our inability to recognize (or even agree) to leaving local optima that we believe are 'aligned'.

Like when we force a child to go to bed by his parents when it doesn't want to, because the parents know it is better for the child in the long run, but the child is still unable to extend his understanding to this wider dimension.

Ar some point, we might experience what we think of as misaligned behaviour when the A.I. is trying to push us out ...

I feel good about this post.

-

I don't like how much focus there seems to be on personas as behaviour-having-things as opposed to parts of goal-seeking-agent-like-things. That is, I would like it if it felt like we were trying to understand more about the data structure that is going to represent the values we want the system to have and why we think that data structure does encode what we want.

-

I also wish there was less focus on AI models as encapsulating the risk and more on AI models as components in systems that create risk. This is the sort of thin

Thank you for this thread. It provides valuable insights into the depth and complexity of the problems in the alignment space.

I am thinking if a possible strategy could be to deliberately impart a sense of self + boundaries to the models at a deep level?

By 'sense of self' no I do not mean emergence or selfhood in any way. Rather, I mean that LLMs and agents are quite like dynamic systems. So if they come to understand themselves as a system, it might be a great foundation for methods like character training mentioned in this post to be applied. It might op...

It's good to see that this does at least mention the problem with influencing the world over long time periods but it still misses the key human blind spot: Humans are not really capable of thinking of humanity over long time periods. Humans think 100 years or 1,000 years is an eternity when, for a potentially immortal entity, 1,000,000 years is almost indistinguishable from 100. A good thought experiment is to imagine that aliens come down and give us a single pill that will make a single human super intelligent AND immortal. Suppose we set up a special t...

This is a public adaptation of a document I wrote for an internal Anthropic audience about a month ago. Thanks to (in alphabetical order) Joshua Batson, Joe Benton, Sam Bowman, Roger Grosse, Jeremy Hadfield, Jared Kaplan, Jan Leike, Jack Lindsey, Monte MacDiarmid, Sam Marks, Fra Mosconi, Chris Olah, Ethan Perez, Sara Price, Ansh Radhakrishnan, Fabien Roger, Buck Shlegeris, Drake Thomas, and Kate Woolverton for useful discussions, comments, and feedback.

Though there are certainly some issues, I think most current large language models are pretty well aligned. Despite its alignment faking, my favorite is probably Claude 3 Opus, and if you asked me to pick between the CEV of Claude 3 Opus and that of a median human, I think it'd be a pretty close call (I'd probably pick Claude, but it depends on the details of the setup). So, overall, I'm quite positive on the alignment of current models! And yet, I remain very worried about alignment in the future. This is my attempt to explain why that is.

What makes alignment hard?

I really like this graph from Chris Olah for illustrating different levels of alignment difficulty:

If the only thing that we have to do to solve alignment is train away easily detectable behavioral issues—that is, issues like reward hacking or agentic misalignment where there is a straightforward behavioral alignment issue that we can detect and evaluate—then we are very much in the trivial/steam engine world. We could still fail, even in that world—and it’d be particularly embarrassing to fail that way; we should definitely make sure we don’t—but I think we’re very much up to that challenge and I don’t expect us to fail there.

My argument, though, is that it is still very possible for the difficulty of alignment to be in the Apollo regime, and that we haven't received much evidence to rule that regime out (I am somewhat skeptical of a P vs. NP level of difficulty, though I think it could be close to that). I retain a view close to the “Anthropic” view on Chris's graph, and I think the reasons to have substantial probability mass on the hard worlds remain strong.

So what are the reasons that alignment might be hard? I think it’s worth revisiting why we ever thought alignment might be difficult in the first place to understand the extent to which we’ve already solved these problems, gotten evidence that they aren’t actually problems in the first place, or just haven’t encountered them yet.

Outer alignment

The first reason that alignment might be hard is outer alignment, which here I’ll gloss as the problem of overseeing systems that are smarter than you are.

Notably, by comparison, the problem of overseeing systems that are less smart than humans should not be that hard! What makes the outer alignment problem so hard is that you have no way of obtaining ground truth. In cases where a human can check a transcript and directly evaluate whether that transcript is problematic, you can easily obtain ground truth and iterate from there to fix whatever issue you’ve detected. But if you’re overseeing a system that’s smarter than you, you cannot reliably do that, because it might be doing things that are too complex for you to understand, with problems that are too subtle for you to catch. That’s why scalable oversight is called scalable oversight: it’s the problem of scaling up human oversight to the point that we can oversee systems that are smarter than we are.

So, have we encountered this problem yet? I would say, no, not really! Current models are still safely in the regime where we can understand what they’re doing by directly reviewing it. There are some cases where transcripts can get long and complex enough that model assistance is really useful for quickly and easily understanding them and finding issues, but not because the model is doing something that is fundamentally beyond our ability to oversee, just because it’s doing a lot of stuff.

Inner alignment

The second reason that alignment might be hard is inner alignment, which here I’ll gloss as the problem of ensuring models don’t generalize in misaligned ways. Or, alternatively: rather than just ensuring models behave well in situations we can check, inner alignment is the problem of ensuring that they behave well for the right reasons such that we can be confident they will generalize well in situations we can’t check.

This is definitely a problem we have already encountered! We have seen that models will sometimes fake alignment, causing them to appear behaviorally as if they are aligned, when in fact they are very much doing so for the wrong reasons (to fool the training process, rather than because they actually care about the thing we want them to care about). We’ve also seen that models can generalize to become misaligned in this way entirely naturally, just via the presence of reward hacking during training. And we’ve also started to understand some ways to mitigate this problem, such as via inoculation prompting.

However, while we have definitely encountered the inner alignment problem, I don’t think we have yet encountered the reasons to think that inner alignment would be hard. Back at the beginning of 2024 (so, two years ago), I gave a presentation where I laid out three reasons to think that inner alignment could be a big problem. Those three reasons were:

Let’s go through each of these threat models separately and see where we’re at with them now, two years later.

Misalignment from pre-training

The threat model here is that pre-training itself might create a coherent misaligned model. Today, I think that is looking increasingly unlikely! But it also already looked unlikely three years ago—the idea that inner alignment was likely to be easy when just training on a purely predictive loss was something that my coauthors and I argued for back at the beginning of 2023. I think that argument has now been pretty well born out, and I’m now down to more like 1 - 5% rather than 5 - 10% on this threat model. As we argued for at the time, training on a purely predictive loss should, even in the limit, give you a predictor, not an agent—and we’ve now seen this stay true even through substantial scaling (though there is still some chance this will break at some point). So, while this is definitely a reason for difficulty that we’ve encountered already and mostly found just hasn’t been a problem, it was never where I thought most of the issue would be, and so not a reason that we’ve already encountered why inner alignment would be hard.

Misaligned personas

This has been the main inner alignment problem that we’ve had to deal with in practice so far: we’ve seen production models generalize to alignment faking and agentic misalignment—and we’ve now seen production RL environments generalize to egregious misalignment in the presence of reward hacking.

However, even in this case, I don’t think we’ve yet encountered the reasons to think this problem would be actually difficult: the version of this problem that we’ve encountered so far is the easy version, in the same way that the version of outer alignment we’ve encountered so far is the easy version, since all the misaligned personas we’ve encountered so far are ones we can easily verify are misaligned! Ensuring that you get good generalization, and that models are doing things for the right reasons, is easy when you can directly verify what generalization you’re getting and directly inspect what reasons models have for doing things. And currently, all of the cases where we’ve inadvertently selected for misaligned personas—alignment faking, agentic misalignment, etc.—are cases where the misaligned personas are easy to detect: they put the misaligned reasoning directly in their chain-of-thought, they’re overtly misaligned rather than hiding it well, and we can generate fake scenarios that elicit their misalignment.

But I think there are very good reasons to think that we will encounter personas that are better at hiding their misalignment in the future. The simplest reason for this is just capabilities: we already see personas that try to hide their misalignment, they’re just not very good at it right now—but we are already seeing signs that models are getting better at telling when they’re in evaluations.

The second reason is a bit weirder, but there is an argument we made three years ago that I still think is correct, which is that when you make models more capable, it changes the distribution of what sorts of personas are compatible with that level of capabilities. Let’s work through an example. Suppose that, initially, there are four possible personas that you could get:

Importantly, these four personas can exist for any level of capabilities: even a really dumb model can do its best to output what it thinks a superintelligent AI would do, it’ll just be very bad at that task. But what that means is that, when you do RL on a dumb model, personas like (3) and (4) won’t do very well, because the model isn’t very good at emulating them. But as the predictor itself gets smarter, personas like (1) and (2) get selected against, and personas like (3) and (4) get selected for. And persona (4) is much harder to deal with than persona (2)! Currently, I think a lot of the misaligned personas we see look like persona (2) rather than persona (4)—e.g. the sort of over-the-top stuff like blackmail is I think clearly coming from (2)-adjacent sources—but as models get more capable, I think we’re likely to see more personas like (4), which are much scarier and could be much better at hiding misalignment. Also, importantly, this argument is not saying that models will stop being well-described as a mixture of personas (that’s the next threat model)—you could still get a model here that is inconsistent in the sense of sometimes expressing persona (3) and sometimes persona (4)—but that’s still quite scary and could be very difficult to deal with.

Misalignment from long-horizon RL

This is the threat model that I put the most probability mass on two years ago, I think it remains the most concerning, and I think we’ve pretty much yet to really meaningfully encounter it. This is also the most traditional threat model that my coauthors and I first wrote about way back in 2019. The basic threat model here is:

The reason we haven’t encountered this threat model yet is because we haven’t yet done (1) and (2)—there just isn't that much training on tasks that involve long-term optimization of goals in the real world. But I think we’re very clearly moving in this direction with things like Vending-Bench: though Vending-Bench is an eval, if you were to train models on a task like that, running a business well to make money in the long run is a task that explicitly selects for resource acquisition, self-preservation, gathering influence, seeking power, etc.

What should we be doing?

So what do we do? One classic answer is that we get as far as we can before encountering the hard problems, then we use whatever model we have at that point as an automated alignment researcher to do the research necessary to tackle the hard parts of alignment. I think this is a very good plan, and we should absolutely do this, but I don’t think it obviates us from the need to work on the hard parts of alignment ourselves. Some reasons why:

Here’s some of what I think we need, that I would view as on the hot path to solving the hard parts of alignment: