This post deserves to be remembered as a LessWrong classic.

There are several problems that are fundamentally about attaching very different world models together and transferring information from one to the other.

In general, we can solve these problems using shared variables and shared sub-structures that are present in both models.

Natural latents are a step toward solving all of these problems, via describing a subset of variables/structures that we should expect to find across all WMs (and more importantly, some of the conditions required for them to be present).

A natural latent should be extremely useful for any WM that contains variables which share redundant information. I think we can expect this to be common when highly redundant observations are compressed.

For example: If the ~same observation happens more than once, then any learner that generalizes well is going to notice this. It must somehow store the duplicated information (as well as each of the places where it is duplicated). That shared information is a natural latent. The result in this post suggests that this summary information should be isomorphic between agents, under the right conditions.[2]

As far as I know, it's an open question which properties of environments&agents imply lots of natural latents.

The current state of this work has some limitations:

If this line of research goes well, I hope that we will have theorems that say something like:

"For some bounded agent design, given observations of some complicated well-understood data-generating structure Z, and enough compute / attentional resources, the agent will learn a model of Z which contains parts x,y,w (each with predicable levels of approximate isomorphism to parts of the real Z). Upon observing more data, we can expect some parts (x,y) of this structure to remain unchanged."

Think of an ontology the choice of variables in a particular Bayes net, for our current purposes.

I'm leaning on the algorithmic definition of natural latents here.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that any article about the hidden nature of reality will not garner close to the number of comments as one about your sexy sexy homies. As the inaugural and possibly lone commenter, let me say I'm delighted to see finally this long-awaited post. I look forward to do a deep dive soon.

I sometimes use the notion of natural latents in my own thinking - it's useful in the same way that the notion of Bayes networks is useful.

A frame I have is that many real world questions consist of hierarchical latents: for example, the vitality of a city is determined by employment, number of companies, migration, free-time activities and so on, and "free-time activities" is a latent (or multiple latents?) on its own.

I sometimes get use of assessing whether a topic at hand is a high-level or low-level latent and orienting accordingly. For example: if the topic at hand is "what will the societal response to AI be like?", it's by default not a great conversational move to talk about one's interactions with ChatGPT the other day - those observations are likely too low-level[1] to be informative about the high-level latent(s) under discussion. Conversely, if the topic at hand is low-level, then analyzing low-level observations is very sensible.

(One could probably have derived the same every-day lessons simply from Bayes nets, without the need for natural latent math, but the latter helped me clarify "hold on, what are the nodes of the Bayes net?")

But admittedly, while this is a fun perspective to think about, I haven't got that much value out of it so far. This is why I give this post +4 instead of +9 for the review.

And, separately, too low sample size.

There's a thing I keep thinking of when it comes to natural latents. In social science one often speaks of statistical sex differences, e.g. women tend to be nicer than men. But these sex differences aren't deterministic, so one can't derive them from simply meeting 1 woman and 1 man. It feels like this is in tension with the insensitivity condition, like that this only permits universal generalizations (I guess stuff like anatomy?). But also I haven't really practiced natural latents at all so I sort of expect to be using them in a suboptimal way. Maybe you have a better idea?

Like I mean obviously one can deterministically recover it when one considers large samples of people, so it seems like maybe the "statistical man" and "statistical woman" concepts are different from the "universal man" and "universal woman" concepts. Not entirely sure this is a good approach though.

It feels like this is in tension with the insensitivity condition, like that this only permits universal generalizations (I guess stuff like anatomy?)

Quite the opposite! In that example, what the insensitivity condition would say is: if I get a big sample of people (roughly 50/50 male/female), and quantify the average niceness of men and women in that sample, then I expect to get roughly the same numbers if I drop any one person (either man or woman) from the sample. It's the statistical average which has to be insensitive; any one "sample" can vary a lot.

That said, it does need to be more like a universal generalization if we impose a stronger invariance condition. The strongest invariance condition would say that we can recover the latent from any one "sample", which would be the sort of "universal generalization" you're imagining. Mathematically, the main thing that would give us is much stronger approximations, i.e. smaller 's.

Probabilities of zero are extremely load-bearing for natural latents in the exact case...

Dumb question: Can you sketch out an argument for why this is the case and/or why this has to be the case? I agree that ideally/morally this should be true, but if we're already accepting a bounded degree of error elsewhere, what explodes if we accept it here?

Consider the exact version of the redundancy condition for latent over :

and

Combine these two and we get, for all :

OR

That's the foundation for a conceptually-simple method for finding the exact natural latent (if one exists) given a distribution :

Does that make sense?

Let's say every day at the office, we get three boxes of donuts, numbered 1, 2, and 3. I grab a donut from each box, plunk them down on napkins helpfully labeled X1, X2, and X3. The donuts vary in two aspects: size (big or small) and flavor (vanilla or chocolate). Across all boxes, the ratio of big to small donuts remains consistent. However, Boxes 1 and 2 share the same vanilla-to-chocolate ratio, which is different from that of Box 3.

Does the correlation between X1 and X2 imply that there is no natural latent? Is this the desired behavior of natural latents, despite the presence of the common size ratio? (and the commonality that I've only ever pulled out donuts; there has never been a tennis ball in any of the boxes!)

If so, why is this what we want from natural latents? If not, how does a natural latent arise despite the internal correlation?

My take would be to split each "donut" variable into "donut size" and "donut flavour" . Then there a natural latent for the whole set of variables, and no natural latent for the whole set. basically becomes the "other stuff in the world" variable relative to .

Granted, there's an issue in that we can basically do that for any set of variables , even entirely unrelated ones: deliberately search for some decomposition of into an and an such that there's a natural latent for . I think some more practical measures could be taken into account here, though, to enure that the abstractions we find are useful. For example, we can check the relative information contents/entropies of and , thereby measuring "how much" of the initial variable-set we're abstracting over. If it's too little, that's not a useful abstraction.[1]

That passes my common-sense check, at least. It's essentially how we're able to decompose and group objects along many different dimensions. We can focus on objects' geometry (and therefore group all sphere-like objects, from billiard balls to planets to weather balloons) or their material (grouping all objects made out of rock) or their origin (grouping all man-made objects), etc.

Each grouping then corresponds to an abstraction, with its own generally-applicable properties. E. g., deriving a "sphere" abstraction lets us discover properties like "volume as a function of radius", and then we can usefully apply that to any spherical object we discover. Similarly, man-made objects tend to have a purpose/function (unlike natural ones), which likewise lets us usefully reason about that whole category in the abstract.

(Edit: On second thoughts, I think the obvious naive way of doing that just results in containing all mutual information between , with the "abstraction" then just being said mutual information. Which doesn't seem very useful. I still think there's something in that direction, but probably not exactly this.)

Relevant: Finite Factored Sets, which IIRC offer some machinery for these sorts of decompositions of variables.

This branch of research is aimed at finding a (nearly) objective way of thinking about the universe. When I imagine the end result, I imagine something that receives a distribution across a bunch of data, and finds a bunch of useful patterns within it. At the moment that looks like finding patterns in data via find_natural_latent(get_chunks_of_data(data_distribution))

or perhaps showing that find_top_n(n, (chunks, natural_latent(chunks)) for chunks in all_chunked_subsets_of_data(data_distribution), key=lambda chunks, latent: usefulness_metric(latent))

is a (convergent sub)goal of agents. As such, the notion that the donuts' data is simply poorly chunked - which needs to be solved anyway - makes a lot of sense to me.

I don't know how to think about the possibilities when it comes to decomposing . Why would it always be possible to decompose random variables to allow for a natural latent? Do you have an easy example of this?

Also, what do you mean by mutual information between , given that there are at least 3 of them? And why would just extracting said mutual information be useless?

If you get the chance to point me towards good resources about any of these questions, that would be great.

Regarding chunking: a background assumption for me is that the causal structure of the world yields a natural chunking, with each chunk taking up a little local "voxel" of spacetime.

Some amount spacetime-induced chunking is "forced upon" an embedded agent, in some sense, since their sensors and actuators are localized in spacetime.

Now, there's still degrees of freedom in taking more or less coarse-grained chunkings, and more or less coarse-graining differentially along different spacetime directions or in different places. But I expect that spacetime locality mostly nails down what we need as a starting point for convergent chunking.

Also, what do you mean by mutual information between , given that there are at least 3 of them?

You can generalize mutual information to N variables: interaction information.

Why would it always be possible to decompose random variables to allow for a natural latent?

Well, I suppose I overstated it a bit by saying "always"; you can certainly imagine artificial setups where the mutual information between a bunch of variables is zero. In practice, however, everything in the world is correlated with everything else, so in a real-world setting you'll likely find such a decomposition always, or almost always.

And why would just extracting said mutual information be useless?

Well, not useless as such – it's a useful formalism – but it would basically skip everything John and David's post is describing. Crucially, it won't uniquely determine whether a specific set of objects represents a well-abstracting category.

The abstraction-finding algorithm should be able to successfully abstract over data if and only if the underlying data actually correspond to some abstraction. If it can abstract over anything, however – any arbitrary bunch of objects – then whatever it is doing, it's not finding "abstractions". It may still be useful, but it's not what we're looking for here.

Concrete example: if we feed our algorithm 1000 examples of trees, it should output the "tree" abstraction. If we feed our algorithm 200 examples each of car tires, trees, hydrogen atoms, wallpapers, and continental-philosophy papers, it shouldn't actually find some abstraction which all of these objects are instances of. But as per the everything-is-correlated argument above, they likely have non-zero mutual information, so the naive "find a decomposition for which there's a natural latent" algorithm would fail to output nothing.

More broadly: We're looking for a "true name" of abstractions, and mutual information is sort-of related, but also clearly not precisely it.

We could remove information from For instance, could be a bit indicating whether the temperature is above 100°C

I don't understand how this is less information than a bit indicating whether the temperature is above 50C. Specifically, given a bit telling you whether the temperature is above 50C, how do you know whether the temperature is above 100C or between 50C and 100C?

I know very, very little about category theory, but some of this work regarding natural latents seem to absolutely smack of it. There seems to be a fairly important three-way relationship between causal models, finite factored sets, and Bayes nets.

To be precise, any causal model consisting of root sets , downstream sets , and functions mapping sets to downstream sets like must, when equipped with a set of independent probability distributions over B, create a joint probability distribution compatible with the Bayes net that's isomorphic to the causal model in the obvious way. (So in the previous example, there would be arrows from only , , and to ) The proof of this seems almost trivial but I don't trust myself not to balls it up somehow when working with probability theory notation.

In the resulting Bayes net, one "minimal" natural latent which conditionally separates and is just the probabilities over just the root elements from which both and depend on. It might be possible to show that this "minimal" construction of satisfies a universal property, and so other which is also "minimal" in this way must be isomorphic to .

I think you could make the first theorem in the post (simplified fundamental theorem on two variables) easier to understand to a novice if you explicitly clarified that the conclusion diagram Λ' -> Λ -> X is the same as Λ' <- Λ -> X by the chain rerooting rule, and perhaps use the latter diagram in the picture as it more directly makes clear the idea of mediation/inducing independence.

Probabilities of zero are extremely load-bearing for natural latents in the exact case, and probabilities near zero are load-bearing in the approximate case; if the distribution is zero nowhere, then it can only have a natural latent if the ’s are all independent (in which case the trivial variable is a natural latent).

I'm a bit confused why this is the case. It seems like in the theorems, the only thing "near zero" is that D_KL (joint, factorized) < epsilon ~= 0 . But you. can satisfy this quite easily even with all probabilities > 0.

E.g. the trivial case where all variables are completely independents satisfies all the conditions of your theorem, but can clearly have every pair of probabilities > 0. Even in nontrivial cases, this is pretty easy (e.g. by mixing in irreducible noise with every variable).

Roughly speaking, all variables completely independent is the only way to satisfy all the preconditions without zero-ish probabilities.

This is easiest to see if we use a "strong invariance" condition, in which each of the must mediate between and . Mental picture: equilibrium gas in a box, in which we can measure roughly the same temperature and pressure () from any little spatially-localized chunk of the gas (). If I estimate a temperature of 10°C from one little chunk of the gas, then the probability of estimating 20°C from another little chunk must be approximately-zero. The only case where that doesn't imply near-zero probabilities is when all values of both chunks of gas always imply the same temperature, i.e. only ever takes on one value (and is therefore informationally empty). And in that case, the only way the conditions are satisfied is if the chunks of gas are unconditionally independent.

Hm, it sounds like you're claiming that if each pair of x, y, z are pairwise independent conditioned on the third variable, and p(x, y, z) =/= 0 for all x, y, z with nonzero p(x), p(y), p(z), then ?

I tried for a bit to show this but couldn't prove it, let alone the general case without strong invariance. My guess is I'm probably missing something really obvious.

Yeah, that's right.

The secret handshake is to start with " is independent of given " and " is independent of given ", expressed in this particular form:

... then we immediately see that for all such that .

So if there are no zero probabilities, then for all .

That, in turn, implies that takes on the same value for all Z, which in turn means that it's equal to . Thus and are independent. Likewise for and . Finally, we leverage independence of and given :

(A similar argument is in the middle of this post, along with a helpful-to-me visual.)

Right, the step I missed on was that P(X|Y) = P(X|Z) for all y, z implies P(X|Z) = P(X). Thanks!

Absent feedback, today I read further, to the premise of the maxent conjecture. Let X be 100 numbers up to 1 million, rerolled until the remainder of their sum modulo 1000000 ends up 0 or 1. (X' will have sum-remainder circa 50 or circa -50.) Given X', X1 has a 25%/50%/25% pattern around X'1. Given X2 through X100, X1 has a 50%/50% distribution. So the (First/Strong) Universal Natural Latent Conjecture fails, right?

I believe no natural latent exists in that case?

The Universal Natural Latent Conjecture doesn't say X' is always a natural latent, it says X' is a natural latent if any natural latent exists.

One thing that initially stood out to me on the fundamental theorem was: where did the arrow come from? It 'gets introduced' in the first bookkeeping step (we draw and then reorder the subgraph at each .

This seemed suspicious to me at first! It seemed like kind of a choice, so what if we just didn't add that arrow? Could we land at a conclusion of AND ? That's way too strong! But I played with it a bit, and there's no obvious way to do the second frankenstitch which brings everything together unless you draw in that extra arrow and rearrange. You just can't get a globally consistent topological ordering without somehow becoming ancesterable to . (Otherwise the glommed variables interfere with each other when you try to find 's ancestors in the stitch.)

Still, this move seems quite salient - in particular that arrow-addition feels something like the 'lossiest' step in the proof (except for the final bookkeeping which gloms all the together, implicitly drawing a load of arrows between them all)?

Is my understanding correct or am I missing something?

E.g. in the biased die example, every each die roll sample has, in expectation, the same information content, which is the die bias + random noise, and so the mutual info of n rolls is the die bias itself

(where "different X's" above can be thought of as different (or the same) distributions over the observation space of X corresponding to the different sampling instances, perhaps a non-standard framing)

First bullet is correct, second bullet is close but not quite right. Just one sample of a natural latent will give you (approximately) all the mutual information between the X's, and can give you some additional "noise" as well.

E.g. in the biased die example with many rolls, we can sample the bias given the rolls. Because that distribution is very pointy the sample will be very close to the "true bias", that one sample will capture approximately-all of the mutual information between the rolls.

(Note: I did skip a subtle step there - our natural latents need a stronger condition than just "close to the true bias" in this example, since the low-order bits of the latent could in-principle contain a bunch of relevant information which the true bias doesn't; that would mess everything up. And indeed, that would mess everything up if we tried to use e.g. the empirical frequencies rather than a sample from P[bias | X]: given all but one die roll and the empirical frequencies calculated from all of the die rolls, we could exactly calculate the outcome of the remaining die roll. That's why we do the sampling thing; the little bit of noise introduced by sampling is load-bearing, since it wipes out info in those low-order bits.

... but that's a subtlety which you should not worry about until after the main picture makes sense conceptually.)

Speaking as an (ex-)scientist, the fact that natural latents exist, can be found, and are well defined and basically unique for a systems feels… blindingly obvious: we do this all the time. But I gather we never previously had a description of their necessary properties in term of Bayes nets before, nor a proof of in what sense they are unique. I don't think I was ever very worried that AI was going to discover an entirely different ontology for physics so different that pressure or temperature were not well-defined abstractions represented in it, but I also didn't have a uniqueness proof demonstrating that fact, and with the fate of the human race potentially on the line, that's a reassuring thing to have. Physicists often have a tendency to take on trust things that any mathematician would be aghast at, just because they seem to work in practice. [But then, neither have I ever figured out why anyone thinks the diamond-maximization problem is hard, as opposed to just tedious (you just have to list your purity specifications in isotopic and crystalographic terms, and then put it inside a standard causal wrapper).]

In standard form, a natural latent is always approximately a deterministic function of . Specifically: .

What does the arrow mean in this expression?

I've been doing a deep dive on this post, and while the main theorems make sense I find myself quite confused about some basic concepts. I would really appreciate some help here!

The Resampling stuff is a bit confusing too:

if we have a natural latent , then construct a new natural latent by resampling conditional on (i.e. sample from ), independently of whatever other stuff we’re interested in.

And finally:

In standard form, a natural latent is always approximately a deterministic function of . Specifically: .

...

Suppose there exists an approximate natural latent over . Construct a new random variable sampled from the distribution . (In other words: simultaneously resample each given all the others.) Conjecture: is an approximate natural latent (though the approximation may not be the best possible). And if so, a key question is: how good is the approximation?

Where is the top result proved, and how is this statement different from the Universal Natural Latent Conjecture below? Also is this post relevant to either of these statements, and if so, does that mean they only hold under strong redundancy?

So 'latents' are defined by their conditional distribution functions whose shape is implicit in the factorization that the latents need to satisfy, meaning they don't have to always look like , they can look like , etc, right?

The key idea here is that, when "choosing a latent", we're not allowed to choose ; is fixed/known/given, a latent is just a helpful tool for reasoning about or representing . So another way to phrase it is: we're choosing our whole model , but with a constraint on the marginal . then captures all of the degrees of freedom we have in choosing a latent.

Now, we won't typically represent the latent explicitly as . Typically we'll choose latents such that satisfies some factorization(s), and those factorizations will provide a more compact representation of the distribution than two giant tables for , . For instance, insofar as factors as , we might want to represent the distribution as and (both for analytic and computational purposes).

I don't get the 'standard form' business.

We've largely moved away from using the standard form anyway, I recommend ignoring it at this point.

Also is this post relevant to either of these statements, and if so, does that mean they only hold under strong redundancy?

Yup, that post proves the universal natural latent conjecture when strong redundancy holds (over 3 or more variables). Whether the conjecture does not hold when strong redundancy fails is an open question. But since the strong redundancy result we've mostly shifted toward viewing strong redundancy as the usual condition to look for, and focused less on weak redundancy.

Also does all this imply that we're starting out assuming that shares a probability space with all the other possible latents, e.g. ? How does this square with a latent variable being defined by the CPD implicit in the factorization?

We conceptually start with the objects , , and . (We're imagining here that two different agents measure the same distribution , but then they each model it using their own latents.) Given only those objects, the joint distribution is underdefined - indeed, it's unclear what such a joint distribution would even mean! Whose distribution is it?

One simple answer (unsure whether this will end up being the best way to think about it): one agent is trying to reason about the observables , their own latent , and the other agent's latent simultaneously, e.g. in order to predict whether the other agent's latent is isomorphic to (as would be useful for communication).

Since and are both latents, in order to define , the agent needs to specify . That's where the underdefinition comes in: only and were specified up-front. So, we sidestep the problem: we construct a new latent such that matches , but is independent of given . Then we've specified the whole distribution .

Hopefully that clarifies what the math is, at least. It's still a bit fishy conceptually, and I'm not convinced it's the best way to handle the part it's trying to handle.

First a note:

the two chunks are independent given the pressure and temperature of the gas

I'd be careful here: If the two chunks of gas are in a (closed) room which e.g. was previously colder on one side and warmer on the other and then equilibriated to same temperature everywhere, the space of microscopic states it can have evolved into is much smaller than the space of microscopic states that meet the temperature and pressure requirements (since the initial entropy was lower and physics is deterministic). Therefore in this case (or generally in cases in our simple universe rather than thought experiments where states are randomly sampled) a hypercomputer could see more mutual information between the chunks of gas than just pressure and temperature. I wouldn't call the chunks approximately independent either, the point is that we with our bounded intellects are not able to keep track of the other mutual information.

Main comment:

(EDIT: I might've misunderstood the motivation behind natural latents in what I wrote below.)

I assume you want to use natural latents to formalize what a natural abstraction is.

The " induces independence between all " criterion seems too strong to me.

IIUC you want that if we have an abstraction like "human", you want all the individual humans to share approximately no mutual information conditioned on the "human" abstraction.

Obviously, there are subclusters of humans (e.g. women, children, ashkenazi jews, ...) where members share more properties (which I'd say is the relevant sense of "mutual information" here) than properties that are universally shared among humans.

So given what I intuitively want the "human" abstraction to predict, there would be lots of mutual information between many humans.

However, (IIUC,) your definition of natural latents permits there to be waaayyy more information encoded in the "human" abstraction, s.t. it can predict all the subclusters of humans that exist on earth, since it only needs to be insensitive to removing one particular human from the dataset. This complex human abstraction does render all individual humans approximately independent, but I would say this abstraction seems very ugly and not what I actually want.

I don't think we need this conditional independence condition, but rather something else that finds clusters of thingies which share unusually much (relevant) mutual information.

I like to think of abstractions as similarity clusters. I think it would be nice if we find a formalization of what a cluster of thingies is without needing to postulate an underlying thingspace / space of possible properties, and instead find a natural definition of "similarity cluster" based on (relevant) mutual information. But not sure, haven't really thought about it.

(But possibly I misunderstood sth. If it already exists, feel free to invite me to a draft of the conceptual story behind natural latents.)

Further, assume that mediates between and (third diagram below).

I can't tell if X is supposed to be another variable, distinct from X_1 and X_2, or if it's suppose to be X=(X_1,X_2), or what. EDIT: From reading further it looks like X=(X_1,X_2). This should be clarified where the variables are first introduced. Just to make it clear that this is not obvious even just within the field of Bayes nets, I open up Pearl's "Causality" to page 17 and see "In Figure 1.2, X={X_2} and Y={X_3} are d-separated by Z={X_1}", i.e. X is not assumed to be a vector (X_1, X_2, ...). And obviously there is more variability in other fields.

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2024. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?

Fix some atom of information. It's contained in some of Lambda, X1, X2, and Lambda'. Call the corresponding four statements a,b,c,d. Then you assume "b&c implies a, c&d implies b, b&d implies c, a&d implies b or c.".

These compress into "b&c implies a, d implies a=b=c."; after concluding that, I read that you conclude "d&(b or c) implies a", which seems to be a special case. My approach feels too gainfully simpler, so I'm checking in to ask whether it fails.

Just pasting this into a calculator your expressions don't seem to be equivalent:

e1 = e2: (a ∧ b) ∨ (a ∧ c) ∨ (b ∧ c) ∨ ¬ d

e1 simplifies to (a ∧ b ∧ c) ∨ (¬ a ∧ ¬ b ∧ ¬ c) ∨ (¬ b ∧ ¬ d) ∨ (¬ c ∧ ¬ d)

Natural latents are a relatively elegant piece of math which we figured out over the past year, in our efforts to boil down and generalize various results and examples involving natural abstraction. In particular, this new framework handles approximation well, which was a major piece missing previously. This post will present the math of natural latents, with a handful of examples but otherwise minimal commentary. If you want the conceptual story, and a conceptual explanation for how this might connect to various problems, that will probably be in a future post.

While this post is not generally written to be a "concepts" post, it is generally written in the hope that people who want to use this math will see how to do so.

2-Variable Theorems

This section will present a simplified but less general version of all the main theorems of this post, in order to emphasize the key ideas and steps.

Simplified Fundamental Theorem

Suppose we have:

Further, assume that X mediates between Λ and Λ′ (third diagram below). This last assumption can typically be satisfied by construction in the minimality/maximality theorems below.

Then, claim: Λ mediates between Λ′ and X.

Intuition

Picture Λ as a pipe between X1 and X2. The only way any information can get from X1 to X2 is via that pipe (that’s the first diagram). Λ′ is a piece of information which is present in both X1 and X2 - something we can learn from either of them (that’s the second pair of diagrams). Intuitively, the only way that can happen is if the information Λ′ went through the pipe - meaning that we can also learn it from Λ.

The third diagram rules out three-variable interactions which could mess up that intuitive picture - for instance, the case where one bit of Λ′ is an xor of some independent random bit of Λ and a bit of X.

Qualitative Example

Let X1 and X2 be the low-level states of two spatially-separated macroscopic chunks of an ideal gas at equilibrium. By looking at either of the two chunks, I can tell whether the temperature is above 50°C; call that Λ′. More generally, the two chunks are independent given the pressure and temperature of the gas; call that Λ.

Notice that Λ′ is a function of Λ, i.e. I can compute whether the temperature is above 50°C from the pressure and temperature itself, so Λ mediates between Λ′ and X.

Some extensions of this example:

Intuitive mental picture: in general, Λ can’t have “too little” information; it needs to include all information shared (even partially) across X1 and X2. Λ′, on the other hand, can’t have “too much” information; it can only include information which is fully shared across X1 and X2.

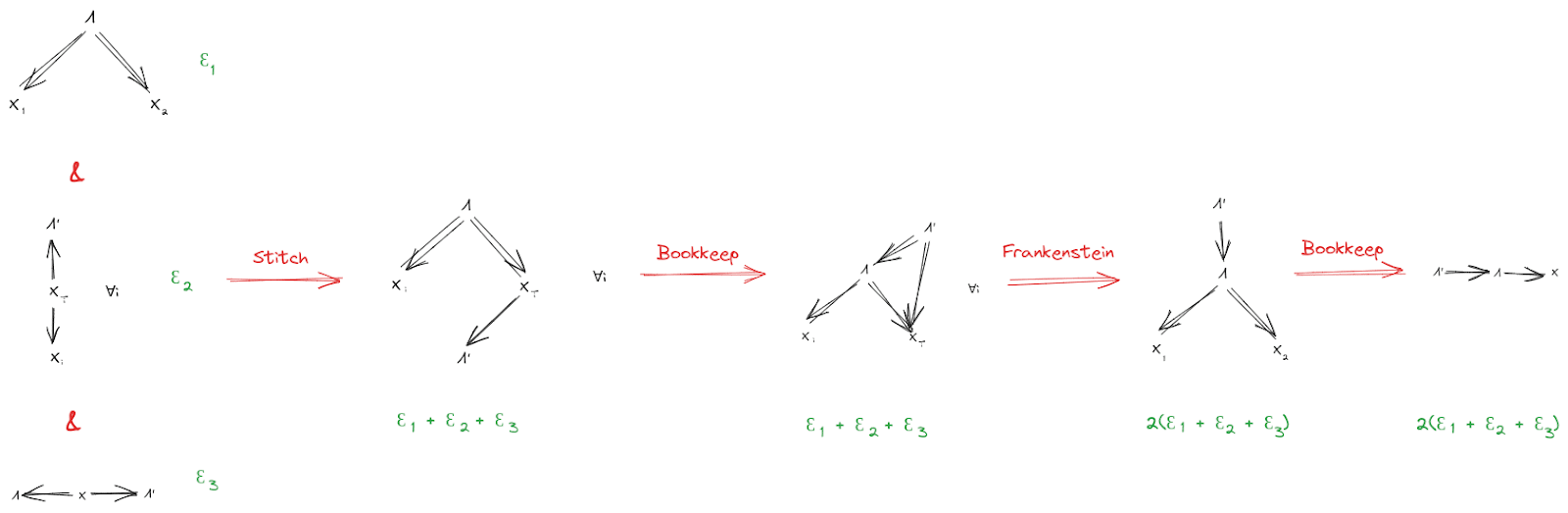

Proof

This is a diagrammatic proof; see Some Rules For An Algebra Of Bayes Nets for how to read it. (That post also walks through a version of this same proof as an example, so you should also look there if you want a more detailed walkthrough.)

(Throughout this post, X¯i denotes all components of X except for Xi.)

Approximation

If the starting diagrams are satisfied approximately (i.e. they have small KL-divergence from the underlying distribution), then the final diagram is also approximately satisfied (i.e. has small KL-divergence from the underlying distribution). We can find quantitative bounds by propagating error through the proof:

Again, see the Algebra of Bayes Nets post for an unpacking of this notation and the proofs for each individual step.

Qualitative Example

Note that our previous example realistically involved approximation: two chunks of an ideal gas won’t be exactly independent given pressure and temperature. But they’ll be independent to a very (very) tight approximation, so our conclusion will also hold to a very tight approximation.

Quantitative Example

Suppose I have a biased coin, with bias θ. Alice flips the coin 1000 times, then takes the median of her flips. Bob also flips the coin 1000 times, then takes the median of his flips. We’ll need a prior on θ, so for simplicity let’s say it’s uniform on [0, 1].

Intuitively, so long as bias θ is unlikely to be very close to ½, Alice and Bob will find the same median with very high probability. So:

The fundamental theorem will then say that the bias approximately mediates between the median (either Alice’ or Bob’s) and the coinflips X.

To quantify the approximation on the fundamental theorem, we first need to quantify the approximation on the second condition (the other two conditions hold exactly in this example, so their ϵ's are 0). Let’s take Λ′ to be Alice’ median. Alice’ flips mediate between Bob’s flips and the median exactly (i.e. X2→X1→Λ′), but Bob’s flips mediate between Alice’ flips and the median (i.e. X1→X2→Λ′) only approximately. Let’s compute that DKL:

DKL(P[X1,X2,Λ′]||P[X1]P[X2|X1]P[Λ′|X2])

=−∑X1,X2P[X1,X2]lnP[Λ′(X1)|X2]

=E[H(Λ′(X1)|X2)]

This is a dirichlet-multinomial distribution, so it will be cleaner if we rewrite in terms of N1:=∑X1, N2:=∑X2, and n:=1000. Λ′ is a function of N1, so the DKL is

=E[H(Λ′(N1)|N2)]

Assuming I simplified the gamma functions correctly, we then get:

P[N2]=1n+1 (i.e. uniform over 0, …, n)

P[N1|N2]=Γ(n+2)Γ(N2+1)Γ(n−N2+1)Γ(n+1)Γ(N1+1)Γ(n−N1+1)Γ(N1+N2+1)Γ(2n−N1−N2+1)Γ(2n+2)

P[Λ′(N1)=0|N2]=∑n1<500P[N1|N2]

P[Λ′(N1)=1|N2]=∑n1>500P[N1|N2]

… and there’s only 10012 values of (N1,N2), so we can combine those expressions with a python script to evaluate everything:

The script spits out H = 0.058 bits. Sanity check: the main contribution to the entropy should be when θ is near 0.5, in which case the median should have roughly 1 bit of entropy. How close to 0.5? Well, with n data points, posterior uncertainty should be of order 1√n, so the estimate of θ should be precise to roughly 130≈.03 in either direction. θ is initially uniform on [0, 1], so distance 0.03 in either direction around 0.5 covers about 0.06 in prior probability, and the entropy should be roughly that times 1 bit, so roughly 0.06 bits. Which is exactly what we found (closer than this sanity check had any business being, really); sanity check passes.

Returning to the fundamental theorem: ϵ1 is 0, ϵ3 is 0, ϵ2 is roughly 0.058 bits. So, the theorem says that the coin’s true bias approximately mediates between the coinflips and Alice’ median, to within 2(ϵ1+ϵ2+ϵ3)≈ 0.12 bits.

Exercise: if we track the ϵ’s a little more carefully through the proof, we’ll find that we can actually do somewhat better in this case. Show that, for this example, the coin’s true bias approximately mediates between the coinflips and Alice’ median to within ϵ2, i.e. roughly 0.058 bits.

Extension: More Stuff In The World

Let’s add another random variable Z to the setup, representing other stuff in the world. Z can have any relationship at all with X, but Λ must still induce independence between X1 and X2. Further, Z must not give any more information about Λ′ than was already available from X1 or X2. Diagrams:

Then, as before, we conclude

For instance, in our ideal gas example, we could take Z to be the rest of the ideal gas (besides the two chunks X1 and X2). Then, our earlier conclusions still hold, even though there’s “more stuff” physically in between X1 and X2 and interacting with both of them.

The proof goes through much like before, with an extra Z dangling everywhere:

And, as before, we can propagate error through the proof to obtain an approximate version:

Natural Latents

Suppose that a single latent variable Λ (approximately) satisfies both the first two conditions of the Fundamental Theorem, i.e.

We call these the “naturality conditions”. If Λ (approximately) satisfies both conditions, then we call Λ a “natural latent”.

Example: if X1 and X2 are two spatially-separated mesoscopic chunks of an ideal gas, then the tuple (pressure, temperature) is a natural latent between the two. The first property (“mediation”) applies because pressure and temperature together determine all the intensive quantities of the gas (like e.g. density), and the low-level state of the gas is (approximately) independent across spatially-separated chunks given those quantities. The second property (“insensitivity”) applies because the pressure and temperature can be precisely and accurately estimated from either chunk.

The Resample

Recall earlier that we said the condition

would be satisfied by construction in our typical use-case. It’s time for that construction.

The trick: if we have a natural latent Λ, then construct a new natural latent by resampling Λ conditional on X (i.e. sample from P[Λ|X]), independently of whatever other stuff Λ′ we’re interested in. The resampled Λ will have the same joint distribution with X as Λ does, so it will also be a natural latent, but it won’t have any “side-channel” interactions with other variables in the system - all of its interactions with everything else are mediated by X, by construction.

From here on out, we’ll usually assume that natural latents have been resampled (and we’ll try to indicate that with the phrase “resampled natural latent”).

Minimality & Maximality

Finally, we’re ready for our main theorems of interest about natural latents.

Assume that Λ is a resampled natural latent over X. Take any other latent Λ′ about which X1 and X2 give (approximately) the same information, i.e.

Then, by the fundamental theorem:

So Λ is, in this sense, the “most informative” latent about which X1 and X2 give the same information:

X1 and X2 give (approximately) the same information about Λ, and for any other latent Λ′ such that X1 and X2 give (approximately) the same information about Λ′, Λ tells us (approximately) everything which Λ′ does about X (and possibly more). This is the “maximality condition”.

Flipping things around: take any other latent Λ′′ which (approximately) induces independence between X1 and X2:

By the fundamental theorem:

So Λ is, in this sense, the “least informative” latent which induces independence between X1 and X2:

Λ (approximately) induces independence between X1 and X2, and for any other latent Λ′′ which (approximately) induces independence between X1 and X2, Λ′′ tells us (approximately) everything which Λ does about X (and possibly more). This is the “minimality condition”.

Further notes:

Example

In the ideal gas example, two chunks of gas are independent given (pressure, temperature), and (pressure, temperature) can be precisely estimated from either chunk. So, (pressure, temperature) is (approximately) a natural latent across the two chunks of gas. The resampled natural latent would be the (pressure, temperature) estimated by looking only at the two chunks of gas.

If there is some other latent which induces independence between the two chunks (like, say, the low-level state trajectory of all the gas in between the two chunks), then the (pressure, temperature) estimated from the two chunks of gas must (approximately) be a function of that latent. And, if there is some other latent about which the two chunks give the same information (like, say, a bit which is 1 if-and-only-if temperature is above 50 °C), then (pressure, temperature) estimated from the two chunks of gas must (approximately) also give that same information.

General Case

Now we move on to more-than-two variables. The proofs generally follow the same structure as the two-variable case, just with more bells and whistles, and are mildly harder to intuit. This time, rather than ease into it, we’ll include approximation and other parts of the world (Z) in the theorems upfront.

The Fundamental Theorem

Suppose we have:

Further, assume that (X,Z) mediates between Λ and Λ′ (third diagram below). This last assumption will be exactly satisfied by construction in the minimality/maximality theorems below.

Then, claim: Λ mediates between Λ′ and (X,Z).

The diagrammatic proof, with approximation:

Note that the error bound is somewhat unimpressive, since it scales with the system size. We can strengthen the approximation mainly by using a stronger insensitivity condition for Λ′ - for instance, if Λ′ is insensitive to either of two halves of the system, then we can reuse the error bounds from the simplified 2-variable case earlier.

Natural Latents

Suppose a single latent Λ (approximately) satisfies both the main conditions

We call these the “naturality conditions”, and we call Λ a (approximate) “natural latent” over X.

The resample step works exactly as before: we’ll generally assume that Λ has been resampled conditional on X, and try to indicate that with the phrase “resampled natural latent”.

Minimality & Maximality

Assume Λ is a resampled natural latent over X. Take any other latent Λ′ about which X¯i gives (approximately) the same information as (X,Z) for any i:

By the fundamental theorem:

So Λ is, in this sense, the “most informative” latent about which all X¯i give the same information:

All X¯i give (approximately) the same information about Λ, and for any other latent Λ′ such that all X¯i give (approximately) the same information about Λ′, Λ tells us (approximately) everything which Λ′ does about X (and possibly more). This is the “maximality condition”.

Flipping things around: take any other latent Λ′′ which (approximately) induces independence between components of X. By the fundamental theorem:

So Λ is, in this sense, the “least informative” latent which induces independence between components of X:

Λ (approximately) induces independence between components of X, and for any other latent Λ′′ which (approximately) induces independence between components of X, Λ′′ tells us (approximately) everything which Λ does about X (and possibly more). This is the “minimality condition”.

Much like the simplified 2-variable case:

Example

Suppose we have a die of unknown bias, which is rolled many times - enough to obtain a precise estimate of the bias many times over. Then, the die-rolls are independent given the bias, and we can get approximately-the-same estimate of the bias while ignoring any one die roll. So, the die’s bias is an approximate natural latent. The resampled natural latent is the bias sampled from a posterior distribution of the bias given the die rolls.

One interesting thing to note in this example: imagine that, instead of resampling the bias given the die rolls, we use the average frequencies from the die rolls. Would that be a natural latent? Answer in spoiler text:

The average frequencies tell us the exact counts of each outcome among the die rolls. So, with the average frequencies and all but one die roll, we can back out the value of that last die roll with certainty: just count up outcomes among all the other die rolls, then see which outcome is “missing”. That means the average frequencies and X¯i together give us much more information about Xi than either one alone; neither of the two natural latent conditions holds.

This example illustrates that the “small” uncertainty in Λ is actually load-bearing in typical problems. In this case, the low-order bits of the average frequencies contain lots of information relevant to X, while the low-order bits of the natural latent don’t.

The most subtle challenges and mistakes in using natural latents tend to hinge on this point.

Other Threads

We’ve now covered the main theorems of interest. This section offers a couple of conjectures, with minimal commentary.

Universal Natural Latent Conjecture

Suppose there exists an approximate natural latent over X1,…,Xn. Construct a new random variable X′, sampled from the distribution (x′↦∏iP[Xi=x′i|X¯i]). (In other words: simultaneously resample each Xi given all the others.) Conjecture: X′ is an approximate natural latent (though the approximation may not be the best possible). And if so, a key question is: how good is the approximation?

Further conjecture: a natural latent exists over X if-and-only-if X is a natural latent over X′.(Note that we can always construct X′, regardless of whether a natural latent exists, and X will always exactly satisfy the first natural latent condition over X′ by construction.) Again, assuming the conjecture holds at all, a key question is to find the relevant approximation bounds.

Maxent Conjecture

Assuming the universal natural latent conjecture holds, whenever there exists a natural latent X′ and X would approximately satisfy both of these two diagrams:

If we forget about all the context and just look at these two diagrams, one natural move is:

… and the result would be that P[X,X′] must be of the maxent form

1Ze∑ijϕij(Xi,X′j)

for some ϕ.

Unfortunately, Hammersley-Clifford requires P[X,X′]>0 everywhere. Probabilities of zero are extremely load-bearing for natural latents in the exact case, and probabilities near zero are load-bearing in the approximate case; if the distribution is zero nowhere, then it can only have a natural latent if the Xi’s are all independent (in which case the trivial variable is a natural latent).

On the other hand, maxent sure does seem to be a theme of natural latents in e.g. physics. So the question is: does some version of this argument work? If there are loopholes, are there relatively few qualitative categories of loopholes which could be classified?

Appendix: Machinery For Latent Variables

If you get confused about things like “what exactly is a latent variable?”, this is the appendix for you.

For our purposes, a latent variable Λ over a random variable X is defined by a distribution function (λ,x↦P[Λ=λ|X=x]) - i.e. a distribution which tells us how to sample Λ from X. For instance, in the ideal gas example, the latent “average temperature” (Λ) can be defined by the distribution of average energy as a function of the gas state (X) - in this case a deterministic distribution, since average energy is a deterministic function of the gas state. As another example, consider the unknown bias of a die (Λ) and a bunch of rolls of the die (X). We would take the latent bias to be defined by the function mapping the rolls X to the posterior distribution of the bias given the rolls (λ↦P[Λ=λ|X]).

So, if we talk about e.g. “existence of a latent Λ∗ with the following properties …”, we’re really talking about the existence of a conditional distribution function (λ∗,x↦P[Λ∗=λ∗|X=x]), such that the random variable Λ∗ which it introduces satisfies the relevant properties. When we talk about “any latent satisfying the following properties …”, we’re really talking about any conditional distribution function (λ,x↦P[Λ=λ|X=x]) such that the variable Λ satisfies the relevant properties.

Toy mental model behind this way of treating latent variables: there are some variables X out in the world, and those variables have some “true frequencies” P[X]. Different agents learn to model those true frequencies using different generative models, and those different generative models each contain their own latents. So the underlying distribution P[X] is fixed, but different agents introduce different latents with different P[Λ|X]; P[Λ|X] is taken to be definitional because it tells us everything about the joint distribution of Λ and X which is not already pinned down by P[X]. (This is probably not the most general/powerful mental model to use for this math, but it’s a convenient starting point.)

Standard Form of a Latent Variable

Suppose that X consists of a bunch of rolls of a biased die, and a latent Λ consists of the bias of the die along with the flip of one coin which is completely independent of the rest of the system. A different latent for the same system consists of just the bias of the die. We’d like some way to say that these two latents contain the same information for purposes of X.

To do that, we’ll introduce a “standard form” Λ∗ (relative to X) for any latent variable Λ:

Λ∗=(x↦P[X=x|Λ])

We’ll say that a latent is “in standard form” if, when we use the above function to put it into standard form, we end up with a random variable equal to the original. So, a latent Λ∗ in standard form satisfies

Λ∗=(x↦P[X=x|Λ∗])

As the phrase “standard form” suggests, putting a standard form latent into standard form leaves it unchanged, i.e. Λ∗:=(x↦P[X=x|Λ]) will satisfy Λ∗=(x↦P[X=x|Λ∗]) for any latent Λ; that’s a lemma of the minimal map theorem.

Conceptually: the standard form throws out all information which is completely independent of X, and keeps everything else. In standard statistics jargon: the likelihood function is always a minimal sufficient statistic. (See the minimal map theorem for more explanation.)

Addendum [Added June 12 2024]: Approximate Isomorphism of Natural Latents Which Are Approximately Determined By X

With just the mediation and redundancy conditions, natural latents aren’t quite unique. For any two natural latents Λ,Λ′ over the same variables X, we have Λ→Λ′→X and Λ′→Λ→X. Intuitively, that means the two natural latents “say the same thing about X”; each mediates between X and the other. But either one could still contain some “noise” which is independent of X, and Λ could contain totally different “noise” than Λ′. (Example: X consists of 1000 flips of a biased coin. One natural latent might be the bias, another might be the bias and one roll of a die which has nothing to do with the coin, and a third natural latent might be the bias and the amount of rainfall in Honolulu on April 7 2033.)

In practice, it’s common for the natural latents we use to be approximately a deterministic function of X. In that case, the natural latent in question can’t include much “noise” independent of X. So intuitively, if two natural latents over X are both approximately deterministic functions of X, then we’d expect them to be approximately isomorphic.

Let’s prove that.

Other than the tools already used in the post, the main new tool will be diagrams like Λ←X→Λ, i.e. X mediates between Λ and itself. (If the same variable appearing twice in a Bayes net is confusing, think of it as two separate variables which are equal with probability 1.) The approximation error for this diagram is the entropy of Λ given X:

DKL(P[X=x,Λ=λ,Λ=λ†]||P[X=x]P[Λ=λ|X=x]P[Λ=λ†|X=x])

=∑x,λ,λ†P[X=x,Λ=λ]I[λ=λ†](lnP[X=x,Λ=λ]+lnI[λ=λ†]−lnP[X=x]−lnP[Λ=λ|X=x]−lnP[Λ=λ†|X=x])

=∑x,λP[X=x,Λ=λ](lnP[X=x,Λ=λ]−lnP[X=x]−lnP[Λ=λ|X=x]−lnP[Λ=λ|X=x])

=−∑x,λP[X=x,Λ=λ]lnP[Λ=λ|X=x]

=EX[H(Λ|X=x)]

So if we want to express “Λ is approximately a deterministic function of X” diagrammatically, we can use the diagram Λ←X→Λ. The approximation error on the diagram is EX[H(Λ|X=x)], which makes intuitive sense: low entropy of Λ given X means that Λ is approximately determined by X.

With that in mind, here’s the full proof of isomorphism, including approximation errors:

The first piece should be familiar: it’s just the fundamental theorem, the main focus of this whole post. As usual, it tells us that either of Λ, Λ′ mediates between the other and X. (Minor note: S is intended to denote a subset in some partition of X; it's a generalization of the notation used in the post, in order to allow for stronger redundancy conditions.)

The next two steps are the new part. They start with two diagrams expressing that Λ and Λ′ are both approximately deterministic functions of X…

… and we conclude that Λ is an approximately deterministic function of Λ′

Since Λ and Λ′ appear symmetrically in the assumptions, the same proof also shows that Λ′ is an approximately deterministic function of Λ. Thus, approximate isomorphism, specifically in the sense that either of the two natural latents has approximately zero entropy given the other.