At some point, I looked at the base rate for discontinuities in what I thought was a random enough sample of 50 technologies. You can get the actual csv here. The base rate for big discontinuities I get is just much higher than 5% that keeps being mentioned throughout the post.

Here are some of the discontinuities that I think can contribute more to this discussion:

- One story on the printing press was that there was a hardware overhang from the Chinese having invented printing, but applying it to their much more difficult to print script. When applying similar methods to the Latin alphabet, printing suddenly became much more efficient. [note: probably wrong, see comment below]

- Examples of cheap physics hacks: The Bessemer process, activated sludge, de Laval nozzles, the Bayer + Hall–Héroult processes.

To overcome small inconveniences, I'm copying the whole csv from that post here:

| Technology | Is there plausibly a discontinuity | Size of the (plausible) discontinuity |

| History of aviation | Yes. With the Wright brothers, who were more analytical and capable than any before them. | Big |

| History of ceramics | Probably not. | |

| History of cryptography | Yes. Plausibly with the invention of the one-time pad. | Medium |

| History of cycling | Yes. With its invention. The dandy horse (immediate antecessor to the bicycle) was invented in a period where there were few horses, but it could in principle have been invented much earlier, and it enabled humans to go much faster. | Small |

| History of film | Probably not. | |

| History of furniture | Maybe. Maybe with the invention of the chair. Maybe with the Industrial Revolution. Maybe in recent history with the invention of more and more comfy models of chairs (e.g., bean bags) | Small |

| History of glass. | Yes. In cheapness and speed with the industrial revolution | Medium |

| Nuclear history | Yes. Both with the explosion of the first nuclear weapon, and with the explosion of the (more powerful) hydrogen bomb | Big |

| History of the petroleum industry | Yes. Petroleum had been used since ancient times, but it took off starting in ~1850 | Big |

| History of photography | Probably not. | |

| History of printing | Yes. With Gutenberg. Hardware overhang from having used printing for a more difficult problem: Chinese characters vs Latin alphabet | Big |

| History of rail transport | Yes. With the introduction of iron, then (Bessemer process) steel over wood, and the introduction of steam engines over horses. Great expansion during the Industrial Revolution. | Medium |

| History of robotics | Maybe. But the 18th-21st centuries saw more progress than the rest combined. | Small |

| History of spaceflight | Yes. With the beginning of the space race. | Big |

| History of water supply and sanitation | Yes. With the Industrial revolution and the push starting in the, say, 1850s to get sanitation in order (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Stink; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Activated_sludge); the discovery/invention of activated sludge might also be another discontinuity. But I’d say it’s mostly the “let us, as a civilization, get our house in order” impulse that led to these inventions. | Medium |

| History of rockets | Yes. With Hale rockets, whose spinning made them more accurate. Then with de Laval nozzles (hypersonic rockets; went from 2% to 64% efficiency). Then plausibly with Germany’s V2 rocket (the German missile program cost levels comparable to the Manhattan project). | Big |

| History of artificial life | Probably not. | |

| History of calendars | Probably not. Maybe with the Khayyam calendar reform in 1079 in the Persian calendar, but it seems too precise to be true. “Because months were computed based on precise times of solar transit between zodiacal regions, seasonal drift never exceeded one day, and also there was no need for a leap year in the Jalali calendar. [...] However, the original Jalali calendar based on observations (or predictions) of solar transit would not have needed either leap years or seasonal adjustments.” | |

| History of candle making | Yes. With industrialization: “The manufacture of candles became an industrialized mass market in the mid 19th century. In 1834, Joseph Morgan, a pewterer from Manchester, England, patented a machine that revolutionized candle making. It allowed for continuous production of molded candles by using a cylinder with a moveable piston to eject candles as they solidified. This more efficient mechanized production produced about 1,500 candles per hour, (according to his patent ". . with three men and five boys [the machine] will manufacture two tons of candle in twelve hours"). This allowed candles to become an easily affordable commodity for the masses” | Small |

| History of chromatography | Probably not. Any of the new types could have been one, though. | |

| Chronology of bladed weapons | Probably not. Though the Spanish tercios were probably discontinuous as an organization method around it. | |

| History of condoms | Probably not | |

| History of the diesel car | Yes. In terms of efficiency: the diesel engine’s point is much more efficient than the gasoline engine. | Medium |

| History of hearing aids | Probably not | |

| History of aluminium | Yes. With the Bayer + Hall–Héroult processes in terms of cheapness. | Big |

| History of automation | Maybe. If so, with controllers in the 1900s, or with the switch to digital in the 1960s. Kiva systems, used by Amazon, also seems to be substantially better than the competition: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazon_Robotics | Medium |

| History of radar | Yes. Development was extremely fast during the war. | Big |

| History of radio | Yes. The first maybe discontinuity was with Marconi realizing the potential of electromagnetic waves for communication, and his superior commercialization. The second discontinuity was a discontinuity in price as vacuum tubes were replaced with transistors, making radios much more affordable. | Big |

| History of sound recording | Maybe. There were different eras, and any of them could have had a discontinuity. For example, magnetic tape recordings were much better than previous technologies | Small |

| History of submarines | Yes. Drebbel's submarine "seemed beyond conventional expectations of what science was thought to have been capable of at the time." It also seems likely that development was sped up during major conflicts (American Civil War, WW1, WW2, Cold War) | Small |

| History of television | Maybe. Work on television was banned during WW2 and picked up faster afterwards. Perhaps with the super-Emitron in the 1930s (“The super-Emitron was between ten and fifteen times more sensitive than the original Emitron and iconoscope tubes and, in some cases, this ratio was considerably greater”) | Medium |

| History of the automobile | Yes. In speed of production with Ford. Afterwards maybe with the Japanese (i.e., Toyota) | Big |

| History of the battery | Maybe. There have been many types of batteries throughout history, each with different tradeoffs. For example, higher voltage and more consistent current at the expense of greater fragility, like the Poggendorff cell. Or the Grove cell, which offered higher current and voltage, at the expense of being more expensive and giving off poisonous nitric oxide fumes. Or the lithium-ion cell, which seems to just have been better, gotten its inventor a Nobel Price, and shows a pretty big jump in terms of, say, voltage. | Small |

| History of the telephone | Probably not. If so, maybe with the invention of the automatic switchboard. | |

| History of the transistor | Maybe. Probably with the invention of the MOSFET; the first transistor which could be used to create integrated circuits, and which started Moore’s law. | Big |

| History of the internal combustion engine | Probably not. If so, jet engines. | |

| History of manufactured fuel gases | Probably not. | |

| History of perpetual motion machines | No. | |

| History of the motorcycle | Probably not. If there is, perhaps in price for the first Vespa in 1946 | |

| History of multitrack recording | Maybe. It is possible that Les Paul’s experimenting was sufficiently radical to be a discontinuity. | Small |

| History of nanotechnology | Probably not | |

| Oscilloscope history | Probably not. However, there were many advances in the last century, and any of them could have been one. | |

| History of paper | Maybe. Maybe with Cai Lun at the beginning. Probably with the industrial revolution and the introduction of wood pulp w/r to cheapness. | Small |

| History of polymerase chain reaction | Yes. Polymerase chain reaction *is* the discontinuity; a revolutionary new technology. It enabled many new other technologies, like DNA evidence in trials, HIV tests, analysis of ancient DNA, etc. | Big |

| History of the portable gas stove | Probably not | |

| History of the roller coaster | Probably not | |

| History of the steam engine | Maybe. The Newcomen engine put together various disparate already existing elements to create something new. Watt’s various improvements also seem dramatic. Unclear abou the others. | Medium |

| History of the telescope | Maybe. If so, maybe after the serendipitous invention/discovery of radio telescopy | Small |

| History of timekeeping devices | Maybe. Plausibly with the industrial revolution in terms of cheapness, then with quartz clocks, then with atomic clocks in terms of precision. | Medium |

| History of wind power | Maybe. If there is, maybe https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_wind_power#Danish_development Tvindcraft | Small |

I think 24% for "there will be a big discontinuity at some point in the history of a field" is pretty reasonable, though I have some quibbles with your estimates (detailed below). I think there are a bunch of additional facts that make me go a lot lower than that on the specific question we have with AI:

- We're talking about a discontinuity at a specific moment along the curve -- not just "there will be a discontinuity in AI progress at some point", but specifically "there will be a discontinuity around the point where AI systems first reach approximately human-level intelligence". Assigning 5% to a discontinuity at a specific region of the curve can easily be compatible with 24% of a discontinuity overall.

- We also know that the field of AI has been around for 60 years and that there is a lot of effort being put into building powerful AI systems. I expect that the more effort is being put into something, the more the low-hanging fruit / "secrets" are already plucked, and the less likely discontinuities are.

- We can't currently point to anything that seems like it should cause a discontinuity in the future. It seems to me like for many of the "physics hack" style of discontinuity, the discontinuity would have been predictable in advance (I'm thinking especially of nukes and spaceflight here). Though possibly this is just hindsight bias on my part.

- We were talking about a huge discontinuity -- that the first time we destroy cities, we will also destroy the Earth. (And I think we're talking about a similarly large discontinuity in the AI case, though I'm not actually sure.) These intuitively feel way larger than your big discontinuities. Though as a counterpoint, I also think AI will be a way bigger deal than most of the other technologies, so a similar discontinuity in some underlying trend could lead to a much bigger discontinuity in terms of impact. (Still, if we talk about "smaller" discontinuities like 1-year doubling of GDP before 4-year doubling of GDP, I put more probability on it, relative to something like "the world looks pretty similar to today's world, and then everyone drops dead".)

(All of these together would push me way lower than 5%, if ignoring model uncertainty / "maybe I'm wrong" + noting that the future is hard to predict.)

It seems to me that the biggest point of disagreement is on (3), and this is why in the conversation I keep coming back to

My impression is that Eliezer thinks that "general intelligence" is a qualitatively different sort of thing than that-which-neural-nets-are-doing, and maybe that's what's analogous to "entirely new physics". I'm pretty unconvinced of this, but something in this genre feels quite crux-y for me.

I do think "look at historical examples" is a good thing to do, so I'll go through each of your discontinuities in turn. Note that I know very little about most of these areas and haven't even read the Wikipedia page for most of them, so lots of things I say could be completely wrong:

- Aviation: I assume you're talking about the zero-to-one discontinuity from "no flight" to "flight"? I do agree that we'll see zero-to-one discontinuities on particular AI capabilities, e.g. language models learn to do arithmetic quite discontinuously. This seems pretty irrelevant to the case with AI. (Notably, the Wright flyer didn't have much of an impact on things people cared about, and not that many people were working on flight to my knowledge.)

- Nukes: Agree that this is a zero-to-one discontinuity from "physics hack" (but note that it did involve a huge amount of effort). Unlike the Wright flyer, it did have a huge impact on things people cared about.

- Petroleum: Not sure what the discontinuity is -- is it that "amount of petroleum used" increased discontinuously? If so, I very much expect such discontinuities to happen; they'll happen any time a better technology replaces a worse technology. (Put another way, the reason to expect continuous progress is that there is optimization pressure on the metric and so the low-hanging fruit / "secrets" have already been taken; there wouldn't have been much optimization pressure on "amount of petroleum used".) I also expect that there has been a discontinuity in "use of neural nets for machine learning", and similarly I expect AI coding assistants will become hugely more popular in the nearish future. The relevant question to me is whether we saw a discontinuity in something like "ability to heat your home" or "ability to travel long distances" or something like that.

- Printing: Going off of AI Impacts' investigation, I'd count this one. I think partly this was because there wasn't much effort going into this. (It looks like when the printing press was invented we were producing ~50,000 manuscripts per year, using about 25,000 person-years of labor. Presumably much much less than that was going into optimizing the process, similarly to how R&D in machine translation is way way lower than the size of the translation market.)

- Spaceflight: Agree that this is a zero-to-one discontinuity from "physics hack" (but note that it did involve a huge amount of effort). Although if you're saying that more resources were spent on it, same comment as petroleum.

- Rockets: I'd love to see numbers, but this does sound like a discontinuity that's relevant to the case with AI. I'd also want to know how much people cared about it (plausibly quite a lot).

- Aluminium: Looking at AI Impacts, I think I'm at "probably a discontinuity relevant to the case with AI, but not a certainty".

- Radar: I'd need more details about what happened here, but it seems like this is totally consistent with the "continuous view" (since "with more effort you got more progress" seems like a pretty central conclusion of the model ).

- Radio: Looking at AI Impacts, I think this one looks more like "lots of crazy fast progress that is fueled by frequent innovations", which seems pretty compatible with the "continuous view" on AI. (Though I'm sympathetic to the critique that the double exponential curve chosen by AI Impacts is an instance of finding a line by which things look smooth; I definitely wouldn't have chosen that functional form in advance of seeing the data.)

- Automobile: I'd assume that there was very little optimization on "speed of production of cars" at the time, given that cars had only just become commercially viable, so a discontinuity seems unsurprising.

- Transistors: Wikipedia claims "the MOSFET was also initially slower and less reliable than the BJT", and further discussion seems to suggest that its benefits were captured with further work and effort (e.g. it was a twentieth the size of a BJT by the 1990s, decades after invention). This sounds like it wasn't a discontinuity to me. What metric did you think it was a discontinuity for?

- PCR: I don't know enough about the field -- sounds like a zero-to-one discontinuity (or something very close, where ~no one was previously trying to do the things PCR does). See aviation.

Transistors: Wikipedia claims "the MOSFET was also initially slower and less reliable than the BJT", and further discussion seems to suggest that its benefits were captured with further work and effort (e.g. it was a twentieth the size of a BJT by the 1990s, decades after invention). This sounds like it wasn't a discontinuity to me.

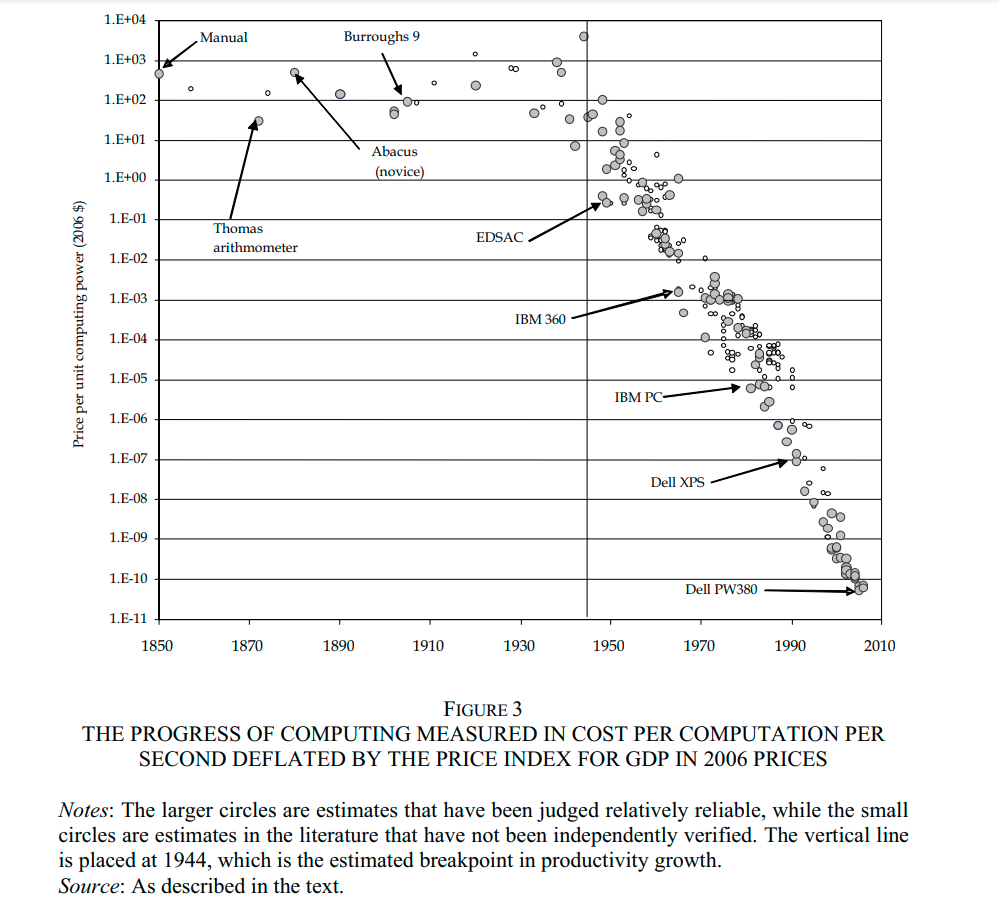

I am also skeptical that the MOSFET produced a discontinuity. Plausibly, what we care about is the number of computations we can do per dollar. Nordhaus (2007) provides data showing that that the rate of progress on this metric was practically unchanged at the time the MOSFET was invented, in 1959.

Your prior is for discontinuities throughout the entire development of a technology, so shouldn't your prior be for discontinuity at any point during the development of AI, rather than discontinuity at or around the specific point when AI becomes AGI? It seems this would be much lower, though we could then adjust upward based on the particulars of why we think a discontinuity is more likely at AGI.

The idea of "hardware overhang" from Chinese printing tech seems extremely unlikely. There was almost certainly no contact between Chinese and European printers at the time. European printing tech was independently derived, and differed from its Chinese precursors in many many important details. Gutenberg's most important innovation, the system of mass-producing types from a matrix (and the development of specialized lead alloys to make this possible), has no Chinese precedent. The economic conditions were also very different; most notably, the Europeans had cheap paper from the water-powered paper mill (a 13th-century invention), which made printing a much bigger industry even before Gutenberg.

When I think about the history of cryptography, I consider there to be a discontinuity at the 1976 invention of Diffie–Hellman key exchange. Diffie–Hellman key exchange was the first asymmetric cryptosystem. Asymmetric cryptography is important because it allows secure communication between two strangers over a externally-monitored channel. Before Diffie–Hellman, it wasn't even clear that asymmetric cryptography was even possible.

That's an interesting example because of how it's a multiple discovery. You know about the secret GCHQ invention, of course, but "Merkle's Puzzles" was invented before D-H: Merkle's Puzzles aren't quite like what you think of by public-key crypto (it's proof of work, in a sense, not trapdoor function, I guess you might say), but they do give a constructive proof that it is possible to achieve the goal of bootstrapping a shared secret. It's not great and can't be improved, but it does it.

It's also another example of 'manufacturing an academic pedigree'. You'll see a lot of people say "Merkle's Puzzles inspired D-H", tracing out a Whig intellectual history of citations only mildly vexed by the GCHQ multiple. But, if you ask Merkle or Diffie themselves, about how Diffie knew about Merkle's then-unpublished work, they'll tell you that Diffie didn't know about the Puzzles when he invented D-H - because nobody understood or liked Merkle's Puzzles (Diffie amusingly explains it as 'tl;dr'). What Diffie did know was that there was a dude called Merkle somewhere who was convinced it could be done, while Diffie was certain it was impossible, and the fact that this dude disagreed with him nagged at him and kept him thinking about the problem until he solved it (making asymmetric/public-key at least a triple: GCHQ, Merkle, and D-H). Reason is adversarial.

The conversation touches on several landmarks in in the history of technology. In this comment, I take a deeper dive into their business, social, scientific and mathematical contexts.

The Wright Brothers

The Wright brothers won a patent in 1906 on airplane flight control (what we now call "ailerons"). A glance through their Wikipedia article suggests they tried to build a monopoly by suing their competitors into oblivion. I get the impression they prioritized legal action over their own business expansion and technological development.

Outside of the medical industry, I can't think of a single technology company in history which dominated an industry primarily through legal action. (Excluding companies founded by fascist oligarchs such as the Japanese zaibatsu.)

Despite all the patents Microsoft holds, I don't know of an instance where they sued a startup for patent infringement. Companies like Microsoft and Oracle don't win by winning lawsuits. That's too uncertain. They win by locking competitors out of their sales channels.

―Are Software Patents Evil? by Paul Graham

Microsoft and Oracle are not known for being afraid of lawsuits or being unwilling to crush their competitors. I think patents just aren't very important.

The Wright brothers had the best flying technology in 1906. The way an inventor captures value is by using a technological edge to start a business that becomes a monopoly by leveraging how technology lets small organizations iterate faster than big organizations. The Wright brothers "didn't personally capture much value by inventing heavier-than-air flying machines" because they let their technical lead slip away by distracting themselves with legal disputes.

They didn't know a secret…

The Wright brothers did have at least one key insight few others in the aviation industry did. Flying a plane is not intuitive to land-dwelling bipeds. They knew the key difficulty would be learning to fly an airplane. But if the first time you learn to fly an airplane is the first time you fly an airplane then you will probably die because landing is harder than taking off. How do they solve the chicken-and-egg (or plane-and-pilot) problem? They tied their engine-less plane to the ground and flew it like a kite to practice flying it under safe conditions.

This kind of insight isn't something you can discover by throwing lots of stuff at the wall because you only get one chance. If you fly a plane and crash you usually don't get to try a different strategy. You just die (as many of the Wright brothers' competitors did).

Another cognitive advantage the Wright brothers had was the conviction that heavier-than-air flight was possible in 1906.

Technical Secrets

secrets = important undiscovered information (or information that's been discovered but isn't widely known), that you can use to get an edge in something….

The most important secrets often stay secret automatically just because they're hard to prove. Suppose you were living in 1905 and you knew for certain that heavier-than-air flight was possible with the available technology. The only way to prove it would be to literally build the world's first airplane, which is a lot of work.

Prediction markets are a step in the right direction.

There seems to be a Paul/Eliezer disagreement about how common these are in general. And maybe a disagreement about how much more efficiently humanity discovers and propagates secrets as you scale up the secret's value?

I think much of the disagreement happens because secrets are concentrated in a small number of people. If you're one of those small number of people then secrets will feel plentiful. You will know more secrets than you have time to pursue. If you're not one of us then secrets will feel rare.

If critical insights are concentrated in a tiny number of people then two claims should be true. ① Most people have zero good technical insights into important problems. ② A extremely tiny minority of people have most of the good technical insights into important problems.

Corollary ① is trivial to confirm.

Corollary ② is confirmed by history.

- Einstein didn't just figure out relativity. He also figured out blackbody radiation and tons of other stuff. These are wildly divergent fields. Blackbody radiation has nothing to do with special or general relativity. Richard Feynman invented Feynman diagrams and the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics.

- Good entrepreneurs don't just get lucky. They win repeatedly. Steve Jobs started Apple, left to start Pixar and then resurrected Apple. Elon Musk founded SolarCity and now runs Tesla and SpaceX. Sam Altman used to run Y-Combinator and now runs OpenAI.

Steam Engines and Nukes

The participants in this conversation reference two energy technologies: nuclear energy and steam energy. The first nuclear bomb had a major immediate impact on world affairs. The first steam engine did not. This is because of math.

With nuclear weapons, the math came first and the technology came second. With steam engines, the technology came first and the math came second. Consequently, the first nuclear weapons were close to physically-optimal (after factoring in infrastructure constraints) whereas the earliest steam engines were not.

Steam Energy

The first commercial steam engine was invented in 1698 by Thomas Savery but the Carnot cycle wasn't proposed by Sadi Carnot until 1824 and the ideal gas law wasn't discovered until 1856.

Imagine building a steam engine 126 years before the discovery of the Carnot cycle. That's like building a nuclear reactor 126 years before . It's like building a nuclear reactor with Benjamin Franklin's knowledge of physics.

The early steampunks did not have sophisticated mathematics on their side. They built their machines first. The mathematics came afterward. The earliest steam engines were extremely inefficient compared to the earliest atomic bombs because they were developed mostly through trial-and-error instead of computing the optimal design mathematically from first principles.

Nuclear Energy

The engineers at the Manhattan Project built a working nuclear device on their first try because they ran careful calculations. For example, they knew the atomic weights of different isotopes. By measuring the energy and velocity of different decay products and plugging them into you can calculate the theoretical maximum yield of a nuclear weapon.

The engineers' objective was to get as close to this theoretical yield as they could. To this end, they knew exactly how much benefit they would get from purifying their fissile material.

Trivia

Idk what the state of knowledge was like in 1800, but maybe they knew that the Sun couldn't be a conventional fire.

Before the knowledge of nuclear energy, one idea of where the Sun got its energy was from gravitational collapse. The physicists used it to compute a maximum age of the universe. The geologists used geological history to compute a minimum age of the universe. The geologists' minimum age was older than the physicists' maximum age. The geologists were right. The physicists were wrong.

You could hardness gravitational potential energy to create superweapons by redirecting asteroids.

I feel like this conversation is getting unstuck because there are fresh angles and analogies. Great balance of meta-commentary too. Please keep at it.

I also think this is creating an important educational and historical document. It’s a time capsule of this community’s beliefs on AGI trajectory, as well as of the current state-of-the-art in rational discourse.

I didn't push this point at the time, but Paul's claim that "GPT-3 + 5 person-years of engineering effort [would] foom" seems really wild to me, and probably a good place to poke at his model more. Is this 5 years of engineering effort and then humans leaving it alone with infinite compute? Or are the person-years of engineering doled out over time?

Unlike Eliezer, I do think that language models not wildly dissimilar to our current ones will be able to come up with novel insights about ML, but there's a long way between "sometimes comes up with novel insights" and "can run a process of self-improvement with increasing returns". I'm pretty confused about how a few years of engineering could get GPT-3 to a point where it could systematically make useful changes to itself (unless most of the work is actually being done by a program search which consumes astronomical amounts of compute).

I didn't push this point at the time, but Paul's claim that "GPT-3 + 5 person-years of engineering effort [would] foom" seems really wild to me, and probably a good place to poke at his model more. Is this 5 years of engineering effort and then humans leaving it alone with infinite compute?

The 5 years are up front and then it's up to the AI to do the rest. I was imagining something like 1e25 flops running for billions of years.

I don't really believe the claim unless you provide computing infrastructure that is externally maintained or else extremely robust, i.e. I don't think that GPT-3 is close enough to being autopoietic if it needs to maintain its own hardware (it will decay much faster than it can be repaired). The software also has to be a bit careful but that's easily handled within your 5 years of engineering.

Most of what it will be doing will be performing additional engineering, new training runs, very expensive trial and error, giant searches of various kinds, terrible memetic evolution from copies that have succeeded at other tasks, and so forth.

Over time this will get better, but it will of course be much slower than humans improving GPT-3 (since GPT-3 is much dumber), e.g. it may take billions of years for a billion copies to foom (on perfectly-reliable hardware). This is likely pretty similar to the time it takes it to improve itself at all---once it has improved meaningfully, I think returns curves to software are probably such that subsequent improvements each come faster than the one before. (The main exception to that latter claim is that your model may have a period of more rapid growth as it picks the low-hanging fruit that programmers missed.)

I'd guess that the main difference between GPT-3-fine-tuned-to-foom and smarter-model-finetuned-to-foom is that the smarter model will get off the ground faster. I would guess that a model of twice the size would take significantly less time (e.g. maybe 25% or 50% as much total compute) though obviously it depends on exactly how you scale.

I don't really buy Eliezer's criticality model, though I've never seen the justification and he may have something in mind I'm missing. If a model a bit smarter than you fooms in 20 years, and you make yourself a bit smarter, then you probably foom in about 20 years. Diminishing returns work roughly the same way whether it's you coming up with the improvements or engineers building you (not quantitatively exactly the same, since you and the engineers will find different kinds of improvements, but it seems close enough for this purpose since you quickly exhaust the fruit that hangs low for you that your programmers missed).

I'd guess the difference with your position is that I'm considering really long compute times. And the main way this seems likely to be wrong is that the curve may be crazy unfavorable by the time you go all the way down to GPT-3 (but compared to you and Eliezer I do think that I'm a lot more optimistic about tiny models run for an extremely long time).

Is this 5 years of engineering effort and then humans leaving it alone with infinite compute?

Maybe something like '5 years of engineering effort to start automating work that qualitatively (but incredibly slowly and inefficiently) is helping with AI research, and then a few decades of throwing more compute at that for the AI to reach superintelligence'?

With infinite compute you could just recapitulate evolution, so I doubt Paul thinks there's a crux like that? But there could be a crux that's about whether GPT-3.5 plus a few decades of hardware progress achieves superintelligence, or about whether that's approximately the fastest way to get to superintelligence, or something.

Paul Christiano makes a slightly different claim here: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/7MCqRnZzvszsxgtJi/christiano-cotra-and-yudkowsky-on-ai-progress?commentId=AiNd3hZsKbajTDG2J

As I read the two claims:

- With GPT-3 + 5 years of effort, a system could be built that would eventually Foom if allowed.

- With GPT-3 + a serious effort, a system could be built that would clearly Foom if allowed.

I think the second could be made into a bet. I tried to operationalise it as a reply to the linked comment.

Here's my attempt at formalizing the tension between gradualism and catastrophism.

- As a background assumption about world-modeling, let's suppose that each person's fine-grained model about how the state of the world moves around can be faithfully represented as a stochastic differential equation driven by a Lévy process. This is a common generalization of Brownian-motion-driven processes, deterministic exponential growth, or Poisson processes (the latter of which only change discontinuously); it basically covers any stochastic model that unfolds over continuous time in way that's Markovian (i.e. the past can affect the future only via the present) and not sensitive to where the point is.

- The Lévy-Khintchine formula guarantees that any Lévy process decomposes into a deterministic drift, a diffusion process (like a Brownian motion with some arbitrary covariance), and a jump process (like a Poisson process with some arbitrary intensity measure).

- Now, we're going to consider some observable predicate, a function from the state space to (like "is there TAI yet?"), and push forward the stochastic model to get a distribution over hitting times. It's worth pointing out that in some sense the entire point of exercises like defining TAI is to introduce a "discontinuity" into everyone's model. In the conversation above, everyone seems to agree as background knowledge that there is a certain point at which something "can FOOM", and that this is a discontinuous event (although the consequent takeoff may be very slow, or not, etc.). What's disputed here is about how one might model the process that leads up to this event.

- The gradualist position is that the jump-process terms are negligible (it's basically a diffusion), and the catastrophist position is that the diffusion-process terms are negligible (it's basically a point process). By "negligible", I mean that, if we have the right model, we should be able to zero out those terms from our underlying Lévy process, and not see much difference in the hitting times.

- Diffusion processes are all kind of alike, and you can make good bets about them based on historical data. Like Gaussians, they are characterized by covariances; finance people love them. This is why someone inclined to take the gradualist position about progress sees the histories of completely unrelated progress as providing meaningful evidence about AGI.

- Jump processes are generally really different from each other, and are hard to forecast from historical data (especially when the intensity is low but the jump distance is high). This is why someone inclined to reject the gradualist position sees little relevance in histories of unrelated progress.

- The gradualist seems likely to have a more diffusion-oriented modeling toolbox in general; they're more likely to reach for kernel density estimation than point process regression; this is why the non-gradualist expects the gradualist to have overestimated the probability that an adequate replacement for Steve Jobs could be found.

- From the gradualist point of view, the non-gradualist lacks intuition about potential-energy landscapes, and so seems to find it plausible that large energy barriers are more likely to be tunneled through in a single jump than crossed gradually by diffusion and ratcheting. The gradualist says this leads the non-gradualist to systematically overestimate the probabilities of such breakthroughs, which perhaps has manifested as a string of unprofitable investments in physical-tech startups.

- It gets confusing at this point because both sides seem to be accusing the other side of overestimating the probabilities of rare events. "Wait, who actually has shorter timelines here, what's going on?" But this debate isn't about the layer where we summarize reality into the one rare event of AGI being deployed, it's about how to think about the underlying state-space model. Both sides think that the other side is focusing on a term of the differential equation that's really negligible as a driver of phase transitions, so their paradigmatic cases to show the other side is overestimating the contribution from those terms are about when they overestimate the probability of phase transitions.

- Finally, I want to point out the obvious third option: neither diffusion terms nor jump terms are negligible. I suspect this is Eliezer's true position, and the one that enables him to "make the obvious boring prediction" (as Paul says) in areas where diffusion is very relevant (by fitting it to historical data), while also saying "sometimes trends break upward" and also saying "the obvious boring predictions about AGI are negligible", all driven from a coherent overall world-model.

I'm wondering if it's a necessary component to an Eliezer-like view on general intelligence and hard takeoff that present-day machine learning methods won't get us to general intelligence.

I know Eliezer expects there to be algorithmic secret sauce. But another feature of his view seems to be that the "progress space (design-differences-to-usefulness-of-output)" is densely packed at the stage where you reach general intelligence. That's what his human examples (von Neumann, Jobs) are always driving at: small differences in brain designs generate vast differences in usefulness of output.

I think that one can have this view about the "density of progress space" without necessarily postulating much secret sauce.

Jessicata made a comment about phase changes in an earlier part of these discussion writeups. I like the thought of general intelligence as a phase transition. Maybe it's a phase transition precisely because the progress space is so densely packed at the stage where capabilities generalize. The world has structure. Sufficiently complex or interesting training processes can lay bare this structure. In the "general intelligence as phase transition" model, "stuff that ML does" is the raw horsepower applied to algorithms that exploit the world's structure. You get immediate benefits from ML-typical "surface-level reasoning." Then, perhaps there's a phase transition when the model starts to improve its ways of reasoning and its model buildling as it goes along. This resembles "foom," but there's no need for software programming (let alone hardware improvements). The recursion is in the model's thoughts: Small differences in thinking abilities let the model come up with better learning strategies and plans, which in turn generates compounding benefits over training run. For comparison, small differences between different human babies compound over the human lifetime.

We are in "culture overhang:" The world contains more useful information on how to think better than ever before. But most of the information is useless. If a model is above the threshold where it can filter out useless information and integrate useful information successfully to improve its reasoning, it reaches an attractor with increasing returns.

I tried to argue for this sort of view here. Some quotes from the liked comment:

If the child in the chair next to me in fifth grade was slightly more intellectually curious, somewhat more productive, and marginally better dispositioned to adopt a truth-seeking approach and self-image than I am, this could initially mean they score 100%, and I score 98% on fifth-grade tests – no big difference. But as time goes on, their productivity gets them to read more books, their intellectual curiosity and good judgment get them to read more unusually useful books, and their cleverness gets them to integrate all this knowledge in better and increasingly more creative ways. I’ll reach a point where I’m just sort of skimming things because I’m not motivated enough to understand complicated ideas deeply, whereas they find it rewarding to comprehend everything that gives them a better sense of where to go next on their intellectual journey. By the time we graduate university, my intellectual skills are mostly useless, while they have technical expertise in several topics, can match or even exceed my thinking even on areas I specialized in, and get hired by some leading AI company. The point being: an initially small difference in dispositions becomes almost incomprehensibly vast over time.

[...]

The standard AI foom narrative sounds a bit unrealistic when discussed in terms of some AI system inspecting itself and remodeling its inner architecture in a very deliberate way driven by architectural self-understanding. But what about the framing of being good at learning how to learn? There’s at least a plausible-sounding story we can tell where such an ability might qualify as the “secret sauce" that gives rise to a discontinuity in the returns of increased AI capabilities. In humans – and admittedly this might be too anthropomorphic – I'd think about it in this way:

If my 12-year-old self had been brain-uploaded to a suitable virtual reality, made copies of, and given the task of devouring the entire internet in 1,000 years of subjective time (with no aging) to acquire enough knowledge and skill to produce novel and for-the-world useful intellectual contributions, the result probably wouldn’t be much of a success. If we imagined the same with my 19-year-old self, there’s a high chance the result wouldn’t be useful either – but also some chance it would be extremely useful. Assuming, for the sake of the comparison, that a copy clan of 19-year olds can produce highly beneficial research outputs this way, and a copy clan of 12-year olds can’t, what does the landscape look like in between? I don’t find it evident that the in-between is gradual. I think it’s at least plausible that there’s a jump once the copies reach a level of intellectual maturity to make plans which are flexible enough at the meta-level and divide labor sensibly enough to stay open to reassessing their approach as time goes on and they learn new things. Maybe all of that is gradual, and there are degrees of dividing labor sensibly or of staying open to reassessing one’s approach – but that doesn’t seem evident to me. Maybe this works more as an on/off thing.

On this view, it seems natural to assume that small differences in hyperparameter tuning, etc., could have gigantic effects on the resulting AI capabilities once you cross the threshold to general intelligence. Even (perhaps) for the first system that crosses the threshold. We're in culture overhang and thinking itself is what goes foom once models reach the point where "better thoughts" start changing the nature of thinking.

I think you could actually predict that nukes wouldn't destroy the planet in 1800 (or at least 1810), and that it would be large organizations rather than mad scientists who built them.

The reasoning for not destroying the earth is similar to the argument that the LHC won't destroy the earth. The LHC is probably fine because high energy cosmic rays hit us all the time and we're fine. Is this future bomb dangerous because it creates a chain reaction? Meteors hit us and volcanos erupt without creating chain reactions. Is this bomb super-dangerous because it collects some material? The earth is full of different concentrations of stuff, why haven't we exploded by chance? (E.g. If x-rays from the first atom bomb were going to sterilize the planet, natural nuclear reactors would have sterilized the planet.) This reasoning isn't airtight, but it's still really strong.

As for project size, it needs to exert effort to get around these restrictions. It's like the question of whether you could blow up the city by putting sand in a microwave. We can be confident that nothing bad happens even without trying it, because things have happened that are similar along a lot of dimensions, and the character of physical law is such that we would have seen a shadow of this city-blowing-up mechanism even in things that were only somewhat similar. To get to blowing up a city it's (very likely) not sufficient to put stuff together in a somewhat new configuration but still using well-explored dimensions, you need to actually make changes in dimensions that we haven't tried yet (like by making your bomb out of something expensive).

These arguments potentially work less well for AGI than they do for nukes, but I think the case of nukes, and Rob's intuitions, are still pretty interesting.

I don't think this is really strong even for nukes. We know that LHC was always going to be extremely unlikely to destroy the planet because we know how it works in great detail, and about the existence of natural particles with the same properties as those in the LHC. If there were no cosmic rays of similar energy to compare against, should our probability for world destruction be larger?

If the aliens told us in 1800 "the bomb will be based on triggering an extremely fast chain reaction" (which is absolutely true) how far upward should we revise our probability?

A hypothetical inconvenient universe in which any nuclear weapon ignites a chain reaction in the environment would be entirely consistent with 1800s observations, and neither cosmic rays nor natural nuclear reactors would rule it out. Beside which, neither of those were known to scientists in 1800, and so could not serve as evidence against the hypothesis anyway.

Of course, we're also in the privileged position of looking back from an extreme event unprecedented in natural conditions that didn't destroy the world. Of course anyone that has already survived one or more such events is going to be biased toward "unprecedented extreme events don't destroy the world, just look at history".

A hypothetical inconvenient universe in which any nuclear weapon ignites a chain reaction in the environment would be entirely consistent with 1800s observations

I think this reveals to me that we've been confusing the map with the territory. People in the 1800s had plenty of information. If they were superintelligent they would have looked at light, and the rules of alchemy, and the color metals make when put into a flame, and figured out relativistic quantum mechanics. Given this, simple density measurements of pure metals will imply the shell structure of the nucleus.

It's not like the information wasn't there. The information was all there, casting shadows over their everyday world. It was just hard to figure out.

Thus, any arguments about what could have been known in 1800 have to secretly be playing by extra rules. The strictest rules are "What do we think an average 1800 natural philosopher would actually say?" In which case, sure, they wouldn't know bupkis about nukes. The arguments I gave could be made using observations someone in 1800 might have found salient, but import a much more modern view of the character of physical law.

What territory? This entire discussion has been about a counterfactual to guide intuition in an analogy. There is no territory here. The analogy is nukes -> AGI, 1800s scientists -> us, bomb that ignites the atmosphere -> rapid ASI.

This makes me extraordinarily confused as to why you are even considering superintelligent 1800s scientists. What does that correspond to in the analogy?

I think you might be saying that just as superintelligent 1800s researchers could determine what sorts of at-least-city-destroying bombs are likely to be found by ordinary human research, that if we were superintelligent then we could determine whether ASI is likely to follow rapidly from AGI?

If so, I guess I agree with that but I'm not sure it actually gets us anywhere? From my reading, Rob's point was about ordinary human 1800s scientists who didn't know the laws of physics that govern at-least-city-destroying bombs, just as we don't know what the universe's rules are for AGI and ASI.

We simply don't know whether the path from here to AGI is inherently (due to the way the universe works) jumpy or smooth, fast or slow. No amount of reasoning about aircraft, bombs, or the economy will tell us either.

We have exactly one example of AGI to point at, and that one was developed by utterly different processes. What we can say is that other primates with a fraction of our brain size don't seem to have anywhere near that fraction of the ability to deal with complex concepts, but we don't know why, nor whether this has any implications for AGI research.

I'll spell out what I see as the point:

The hypothetical 1800s scientists were making mistakes of reasoning that we could now do better than. Not even just because we know more about physics, but because know better how to operate arguments about physical law and novel phenomena.

I find this interesting enough to discuss the plausibility of on its own.

What this says by analogy about Rob's arguments depends on what you translate and what you don't.

On one view, it says that Rob is failing to take advantage of reasoning about intelligence that we could do now, because we know better ways of taking advantage of information than they did in 1800.

On another view, it says that Rob is only failing to take advantage of reasoning that future people would be aware of. The future people would be better than us at thinking about intelligence by as much as we are better than 1800 people at thinking about physics.

I think the first analogy is closer to right and the second is closer to wrong. You can't just make an analogy to a time when people were ignorant and universally refute anyone who claims that we can be less ignorant.

Okay, so we both took completely different things as being "the point". One of the hazards of resorting to analogies.

Regarding the maturity of a field, and whether we can expect progress in a mature field to take place in relatively slow / continuous steps:

Suppose you zoom into ML and don't treat it like a single field. Two things seem likely to be true:

-

(Pretty likely): Supervised / semi-supervised techniques are far, far more mature than techniques for RL / acting in the world. So smaller groups, with fewer resources, can come up with bigger developments / more impactful architectural innovation in the second than in the first.

-

(Kinda likely): Developments in RL / acting in the world are currently much closer to being the bottleneck to AGI than developments in supervised / semi-supervised techniques.

I'm not gonna justify either of these right now, because I think a lot of people would agree with them, although I'm very interested in disagreements.

If we grant that both of these are true, then we could still be in either the Eliezeriverse or Pauliverse. Both are compatible with it. But it sits a tiny bit better in the Eliezeriverse, maybe, because it fits better with clumpy rather than smooth development towards AGI.

Or at least it fits better if we expect AGI to arrive while RL is still clumpy, rather than after a hypothetical 10 or 20 future years of sharpening whatever RL technique turns out to be the best. Although it does fit with Eliezer's short timelines.

catastrophists: when evolution was gradually improving hominid brains, suddenly something clicked - it stumbled upon the core of general reasoning - and hominids went from banana classifiers to spaceship builders. hence we should expect a similar (but much sharper, given the process speeds) discontinuity with AI.

gradualists: no, there was no discontinuity with hominids per se; human brains merely reached a threshold that enabled cultural accumulation (and in a meaningul sense it was culture that built those spaceships). similarly, we should not expect sudden discontinuities with AI per se, just an accelerating (and possibly unfavorable to humans) cultural changes as human contributions will be automated away.

I found the extended Fire/Nuclear Weapons analogy to be quite helpful. Here's how I think it goes:

In 1870 the gradualist and the catastrophist physicist wonder about whether there will ever be a discontinuity in explosive power

- Gradualist: we've already had our zero-to-one discontinuity - we've invented black powder, dynamite and fuses, from now on there'll be incremental changes and inventions that increase explosive power but probably not anything qualitatively new, because that's our default expectation with a technology like explosives where there are lots of paths to improvement and lots of effort exerted

- Catastrophist: that's all fine and good, but those priors don't mean anything if we have already seen an existence proof for qualitatively new energy sources. What about the sun? The energy the sun outputs is overwhelming, enough to warm the entire earth. One day, we'll discover how to release those energies ourselves, and that will give us qualitatively better explosives.

- Gradualist: But we don't know anything about how the sun works! It's probably just be a giant ball of gas heated by gravitational collapse! One day, in some crazy distant future, we might be able to pile on enough gas that gravity implodes and heats it, but that'll require us to be able to literally build stars, it's not going to occur suddenly. We'll pile up a small amount of gas, then a larger amount, and so on after we've given up on assembling bigger and bigger piles of explosives. There's no secret physics there, just a lot of conventional gravitational and chemical energy in one place

- Catastrophist: ah, but don't you know Lord Kelvin calculated the Sun could only shine for a few million years under the gravitational mechanism, and we know the Earth is far older than that? So there has to be some other, incredibly powerful energy source that we've not yet discovered within the sun. And when we do discover it, we know it can under the right circumstances, release enough energy to power the Sun, so it seems foolhardy to assume it'll just happen to be as powerful as our best normal explosive technologies are whenever we make the discovery. Imagine the coincidence if that was true! So I can't say when this will happen or even exactly how powerful it'll be, but when we discover the Sun's power it will probably represent a qualitatively more powerful new energy source. Even if there are many ways to try to tweak our best chemical explosives to be more powerful and/or the potential new sun-power explosives to be weaker, and we'd still not hit the narrow target of the two being roughly on the same level.

- Gradualist: Your logic works, but I doubt Lord Kelvin's calculation

It seems like the AGI Gradualist sees the example of humans like my imagined Nukes Gradualist sees the sun, i.e. just a scale up of what we have now. While the AGI Catastrophist sees Humans as my imagined Nukes Catastrophist sees the sun.

The key disanalogy is that for the Sun case, there's a very clear 'impossibility proof' given by the Nukes Catastrophist that the sun couldn't just be a scale up of existing chemical and gravitational energy sources.

and my best guess about human evolution is pretty similar, it looks like humans are smart enough to foom over a few hundred thousand years [...]

As I see it, humans could indeed foom over a few hundred thousand years, and we're probably 99.9% of the way through the timeline, but we haven't actually foomed yet, not in the sense that we mean by AGI fooming. We might, if given another few hundred years without global disaster.

There are really three completely separate stages of process here.

Almost all of the past few million years has probably been evolution improving hominid brains enough to support general intelligence at all. That was probably reached fifty thousand years ago, maybe even somewhat longer. I think AI is still somewhere in this stage. Our computer hardware may or may not already have capacity to support AGI, but the software is definitely not there yet. In biological terms, I think our AI progress has gone through at least a billion years worth of evolution in two decades, not that these are really comparable.

The last fifty thousand years has mostly been building cultural knowledge, made possible by the previous improvements. We have been building toward the potential that our level of AGI opened up, and I don't think we're close to an endpoint there yet. AI will get a huge jump-start in this stage by adapting much of our knowledge, and even non-AGI systems can make limited use of it to mimic AGI capabilities. It makes the difference between our ancestors wielding sharp rocks and a world spanning civilization, but in my opinion it isn't "foom". If that was all we had to worry about from AGI, it wouldn't be nearly such an existential risk.

The centuries yet to come (without AGI) could have involved using our increasing proficiency with shaping the world to deliberately do what evolution did blindly: improve the fundamental capabilities of cognition itself, and beyond that to use the increased cognitive potential to increase knowledge and cognitive potential further still. This is how I understand the term "foom", and it seems very likely that AI will enter this stage long before humans do.

[not important]

if you go to her house and see the fake skeleton you can update to ~100%.

If you, a stranger, can see the fake skeleton, then presumably it's not really hidden, right?

This post is a transcript of a multi-day discussion between Paul Christiano, Richard Ngo, Eliezer Yudkowsky, Rob Bensinger, Holden Karnofsky, Rohin Shah, Carl Shulman, Nate Soares, and Jaan Tallinn, following up on the Yudkowsky/Christiano debate in 1, 2, 3, and 4.

Color key:

12. Follow-ups to the Christiano/Yudkowsky conversation

12.1. Bensinger and Shah on prototypes and technological forecasting

[Bensinger][16:22] (Sep. 23)

Quoth Paul:

Is this basically saying 'the Wright brothers didn't personally capture much value by inventing heavier-than-air flying machines, and this was foreseeable, which is why there wasn't a huge industry effort already underway to try to build such machines as fast as possible.' ?

My maybe-wrong model of Eliezer says here 'the Wright brothers knew a (Thielian) secret', while my maybe-wrong model of Paul instead says:

[Yudkowsky][17:24] (Sep. 23)

My model of Paul says there could be a secret, but only because the industry was tiny and the invention was nearly worthless directly.

[Christiano][17:53] (Sep. 23)

I mean, I think they knew a bit of stuff, but it generally takes a lot of stuff to make something valuable, and the more people have been looking around in an area the more confident you can be that it's going to take a lot of stuff to do much better, and it starts to look like an extremely strong regularity for big industries like ML or semiconductors

it's pretty rare to find small ideas that don't take a bunch of work to have big impacts

I don't know exactly what a thielian secret is (haven't read the reference and just have a vibe)

straightening it out a bit, I have 2 beliefs that combine disjunctively: (i) generally it takes a lot of work to do stuff, as a strong empirical fact about technology, (ii) generally if the returns are bigger there are more people working on it, as a slightly-less-strong fact about sociology

[Bensinger][18:09] (Sep. 23)

secrets = important undiscovered information (or information that's been discovered but isn't widely known), that you can use to get an edge in something. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/ReB7yoF22GuerNfhH/thiel-on-secrets-and-indefiniteness

There seems to be a Paul/Eliezer disagreement about how common these are in general. And maybe a disagreement about how much more efficiently humanity discovers and propagates secrets as you scale up the secret's value?

[Yudkowsky][18:35] (Sep. 23)

Many times it has taken much work to do stuff; there's further key assertions here about "It takes $100 billion" and "Multiple parties will invest $10B first" and "$10B gets you a lot of benefit first because scaling is smooth and without really large thresholds".

Eliezer is like "ah, yes, sometimes it takes 20 or even 200 people to do stuff, but core researchers often don't scale well past 50, and there aren't always predecessors that could do a bunch of the same stuff" even though Eliezer agrees with "it often takes a lot of work to do stuff". More premises are needed for the conclusion, that one alone does not distinguish Eliezer and Paul by enough.

[Bensinger][20:03] (Sep. 23)

My guess is that everyone agrees with claims 1, 2, and 3 here (please let me know if I'm wrong!):

1. The history of humanity looks less like Long Series of Cheat Codes World, and more like Well-Designed Game World.

In Long Series of Cheat Codes World, human history looks like this, over and over: Some guy found a cheat code that totally outclasses everyone else and makes him God or Emperor, until everyone else starts using the cheat code too (if the Emperor allows it). After which things are maybe normal for another 50 years, until a new Cheat Code arises that makes its first adopters invincible gods relative to the previous tech generation, and then the cycle repeats.

In Well-Designed Game World, you can sometimes eke out a small advantage, and the balance isn't perfect, but it's pretty good and the leveling-up tends to be gradual. A level 100 character totally outclasses a level 1 character, and some level transitions are a bigger deal than others, but there's no level that makes you a god relative to the people one level below you.

2. General intelligence took over the world once. Someone who updated on that fact but otherwise hasn't thought much about the topic should not consider it 'bonkers' that machine general intelligence could take over the world too, even though they should still consider it 'bonkers' that eg a coffee startup could take over the world.

(Because beverages have never taken over the world before, whereas general intelligence has; and because our inside-view models of coffee and of general intelligence make it a lot harder to imagine plausible mechanisms by which coffee could make someone emperor, kill all humans, etc., compared to general intelligence.)

(In the game analogy, the situation is a bit like 'I've never found a crazy cheat code or exploit in this game, but I haven't ruled out that there is one, and I heard of a character once who did a lot of crazy stuff that's at least suggestive that she might have had a cheat code.')

3. AGI is arising in a world where agents with science and civilization already exist, whereas humans didn't arise in such a world. This is one reason to think AGI might not take over the world, but it's not a strong enough consideration on its own to make the scenario 'bonkers' (because AGIs are likely to differ from humans in many respects, and it wouldn't obviously be bonkers if the first AGIs turned out to be qualitatively way smarter, cheaper to run, etc.).

---

If folks agree with the above, then I'm confused about how one updates from the above epistemic state to 'bonkers'.

It was to a large extent physics facts that determined how easy it was to understand the feasibility of nukes without (say) decades of very niche specialized study. Likewise, it was physics facts that determined you need rare materials, many scientists, and a large engineering+infrastructure project to build a nuke. In a world where the physics of nukes resulted in it being some PhD's quiet 'nobody thinks this will work' project like Andrew Wiles secretly working on a proof of Fermat's Last Theorem for seven years, that would have happened.

If an alien came to me in 1800 and told me that totally new physics would let future humans build city-destroying superbombs, then I don't see why I should have considered it bonkers that it might be lone mad scientists rather than nations who built the first superbomb. The 'lone mad scientist' scenario sounds more conjunctive to me (assumes the mad scientist knows something that isn't widely known, AND has the ability to act on that knowledge without tons of resources), so I guess it should have gotten less probability, but maybe not dramatically less?

'Mad scientist builds city-destroying weapon in basement' sounds wild to me, but I feel like almost all of the actual unlikeliness comes from the 'city-destroying weapons exist at all' part, and then the other parts only moderately lower the probability.

Likewise, I feel like the prima-facie craziness of basement AGI mostly comes from 'generally intelligence is a crazy thing, it's wild that anything could be that high-impact', and a much smaller amount comes from 'it's wild that something important could happen in some person's basement'.

---

It does structurally make sense to me that Paul might know things I don't about GPT-3 and/or humans that make it obvious to him that we roughly know the roadmap to AGI and it's this.

If the entire 'it's bonkers that some niche part of ML could crack open AGI in 2026 and reveal that GPT-3 (and the mainstream-in-2026 stuff) was on a very different part of the tech tree' view is coming from a detailed inside-view model of intelligence like this, then that immediately ends my confusion about the argument structure.

I don't understand why you think you have the roadmap, and given a high-confidence roadmap I'm guessing I'd still put more probability than you on someone finding a very different, shorter path that works too. But the argument structure "roadmap therefore bonkers" makes sense to me.

If there are meant to be other arguments against 'high-impact AGI via niche ideas/techniques' that are strong enough to make it bonkers, then I remain confused about the argument structure and how it can carry that much weight.

I can imagine an inside-view model of human cognition, GPT-3 cognition, etc. that tells you 'AGI coming from nowhere in 3 years is bonkers'; I can't imagine an ML-is-a-reasonably-efficient-market argument that does the same, because even a perfectly efficient market isn't omniscient and can still be surprised by undiscovered physics facts that tell you 'nukes are relatively easy to build' and 'the fastest path to nukes is relatively hard to figure out'.

(Caveat: I'm using the 'basement nukes' and 'Fermat's last theorem' analogy because it helps clarify the principles involved, not because I think AGI will be that extreme on the spectrum.)

Oh, I also wouldn't be confused by a view like "I think it's 25% likely we'll see a more Eliezer-ish world. But it sounds like Eliezer is, like, 90% confident that will happen, and that level of confidence (and/or the weak reasoning he's provided for that confidence) seems bonkers to me."

The thing I'd be confused by is e.g. "ML is efficient-ish, therefore the out-of-the-blue-AGI scenario itself is bonkers and gets, like, 5% probability."

[Shah][1:58] (Sep. 24)

(I'm unclear on whether this is acceptable for this channel, please let me know if not)

I think this seems right as a first pass.

Suppose we then make the empirical observation that in tons and tons of other fields, it is extremely rare that people discover new facts that lead to immediate impact. (Set aside for now whether or not that's true; assume that it is.) Two ways you could react to this:

1. Different fields are different fields. It's not like there's a common generative process that outputs a distribution of facts and how hard they are to find that is common across fields. Since there's no common generative process, facts about field X shouldn't be expected to transfer to make predictions about field Y.

2. There's some latent reason, that we don't currently know, that makes it so that it is rare for newly discovered facts to lead to immediate impact.

It seems like you're saying that (2) is not a reasonable reaction (i.e. "not a valid argument structure"), and I don't know why. There are lots of things we don't know, is it really so bad to posit one more?

(Once we agree on the argument structure, we should then talk about e.g. reasons why such a latent reason can't exist, or possible guesses as to what the latent reason is, etc, but fundamentally I feel generally okay with starting out with "there's probably some reason for this empirical observation, and absent additional information, I should expect that reason to continue to hold".)

[Bensinger][3:15] (Sep. 24)

I think 2 is a valid argument structure, but I didn't mention it because I'd be surprised if it had enough evidential weight (in this case) to produce an 'update to bonkers'. I'd love to hear more about this if anyone thinks I'm under-weighting this factor. (Or any others I left out!)

[Shah][23:57] (Sep. 25)

Idk if it gets all the way to "bonkers", but (2) seems pretty strong to me, and is how I would interpret Paul-style arguments on timelines/takeoff if I were taking on what-I-believe-to-be your framework

[Bensinger][11:06] (Sep. 25)

Well, I'd love to hear more about that!

Another way of getting at my intuition: I feel like a view that assigns very small probability to 'suddenly vastly superhuman AI, because something that high-impact hasn't happened before'

(which still seems weird to me, because physics doesn't know what 'impact' is and I don't see what physical mechanism could forbid it that strongly and generally, short of simulation hypotheses)

... would also assign very small probability in 1800 to 'given an alien prediction that totally new physics will let us build superbombs at least powerful enough to level cities, the superbomb in question will ignite the atmosphere or otherwise destroy the Earth'.

But this seems flatly wrong to me -- if you buy that the bomb works by a totally different mechanism (and exploits a different physics regime) than eg gunpowder, then the output of the bomb is a physics question, and I don't see how we can concentrate our probability mass much without probing the relevant physics. The history of boat and building sizes is a negligible input to 'given a totally new kind of bomb that suddenly lets us (at least) destroy cities, what is the total destructive power of the bomb?'.

(Obviously the bomb didn't destroy the Earth, and I wouldn't be surprised if there's some Bayesian evidence or method-for-picking-a-prior that could have validly helped you suspect as much in 1800? But it would be a suspicion, not a confident claim.)

[Shah][1:45] (Sep. 27)

(As phrased you also have to take into account the question of whether humans would deploy the resulting superbomb, but I'll ignore that effect for now.)

I think this isn't exactly right. The "totally new physics" part seems important to update on.

Let's suppose that, in the reference class we built of boat and building sizes, empirically nukes were the 1 technology out of 20 that had property X. (Maybe X is something like "discontinuous jump in things humans care about" or "immediate large impact on the world" or so on.) Then, I think in 1800 you assign ~5% to 'the first superbomb at least powerful enough to level cities will ignite the atmosphere or otherwise destroy the Earth'.

Once you know more details about how the bomb works, you should be able to update away from 5%. Specifically, "entirely new physics" is an important detail that causes you to update away from 5%. I wouldn't go as far as you in throwing out reference classes entirely at that point -- there can still be unknown latent factors that apply at the level of physics -- but I agree reference classes look harder to use in this case.

With AI, I start from ~5% and then I don't really see any particular detail for AI that I think I should strongly update on. My impression is that Eliezer thinks that "general intelligence" is a qualitatively different sort of thing than that-which-neural-nets-are-doing, and maybe that's what's analogous to "entirely new physics". I'm pretty unconvinced of this, but something in this genre feels quite crux-y for me.

Actually, I think I've lost the point of this analogy. What's the claim for AI that's analogous to

?

Like, it seems like this is saying "We figure out how to build a new technology that does X. What's the chance it has side effect Y?" Where X and Y are basically unrelated.

I was previously interpreting the argument as "if we know there's a new superbomb based on totally new physics, and we know that the first such superbomb is at least capable of leveling cities, what's the probability it would have enough destructive force to also destroy the world", but upon rereading that doesn't actually seem to be what you were gesturing at.

[Bensinger][3:08] (Sep. 27)

I'm basically responding to this thing Ajeya wrote:

To which my reply is: I agree that the first AGI systems will be shitty compared to later AGI systems. But Ajeya's Paul-argument seems to additionally require that AGI systems be relatively unimpressive at cognition compared to preceding AI systems that weren't AGI.

If this is because of some general law that things are shitty / low-impact when they "happen for the first time", then I don't understand what physical mechanism could produce such a general law that holds with such force.

As I see it, physics 'doesn't care' about human conceptions of impactfulness, and will instead produce AGI prototypes, aircraft prototypes, and nuke prototypes that have as much impact as is implied by the detailed case-specific workings of general intelligence, flight, and nuclear chain reactions respectively.

We could frame the analogy as:

[Shah][3:14] (Sep. 27)

Seems like your argument is something like "when there's a zero-to-one transition, then you have to make predictions based on reasoning about the technology itself". I think in that case I'd say this thing from above:

(Like, you wouldn't a priori expect anything special to happen once conventional bombs become big enough to demolish a football stadium for the first time. It's because nukes are based on "totally new physics" that you might expect unprecedented new impacts from nukes. What's the analogous thing for AGI? Why isn't AGI just regular AI but scaled up in a way that's pretty continuous?)

I'm curious if you'd change your mind if you were convinced that AGI is just regular AI scaled up, with no qualitatively new methods -- I expect you wouldn't but idk why

[Bensinger][4:03] (Sep. 27)

In my own head, the way I think of 'AGI' is basically: "Something happened that allows humans to do biochemistry, materials science, particle physics, etc., even though none of those things were present in our environment of evolutionary adaptedness. Eventually, AI will similarly be able to generalize to biochemistry, materials science, particle physics, etc. We can call that kind of AI 'AGI'."

There might be facts I'm unaware of that justify conclusions like 'AGI is mostly just a bigger version of current ML systems like GPT-3', and there might be facts that justify conclusions like 'AGI will be preceded by a long chain of predecessors, each slightly less general and slightly less capable than its successor'.

But if so, I'm assuming those will be facts about CS, human cognition, etc., not at all a list of a hundred facts like 'the first steam engine didn't take over the world', 'the first telescope didn't take over the world'.... Because the physics of brains doesn't care about those things, and because in discussing brains we're already in 'things that have been known to take over the world' territory.

(I think that paying much attention at all to the technology-wide base rate for 'does this allow you to take over the world?', once you already know you're doing something like 'inventing a new human', doesn't really make sense at all? It sounds to me like going to a bookstore and then repeatedly worrying 'What if they don't have the book I'm looking for? Most stores don't sell books at all, so this one might not have the one I want.' If you know it's a book store, then you shouldn't be thinking at that level of generality at all; the base rate just goes out the window.)

My way of thinking about AGI is pretty different from saying AGI follows 'totally new mystery physics' -- I'm explicitly anchoring to a known phenomenon, humans.

The analogous thing for nukes might be 'we're going to build a bomb that uses processes kind of like the ones found in the Sun in order to produce enough energy to destroy (at least) a city'.

[Shah][0:44] (Sep. 28)

(And I assume the contentious claim is "that bomb would then ignite the atmosphere, destroy the world, or otherwise have hugely more impact than just destroying a city".)

In 1800, we say "well, we'll probably just make existing fires / bombs bigger and bigger until they can destroy a city, so we shouldn't expect anything particularly novel or crazy to happen", and assign (say) 5% to the claim.

There is a wrinkle: you said it was processes like the ones found in the Sun. Idk what the state of knowledge was like in 1800, but maybe they knew that the Sun couldn't be a conventional fire. If so, then they could update to a higher probability.

(You could also infer that since someone bothered to mention "processes like the ones found in the Sun", those processes must be ones we don't know yet, which also allows you to make that update. I'm going to ignore that effect, but I'll note that this is one way in which the phrasing of the claim is incorrectly pushing you in the direction of "assign higher probability", and I think a similar thing happens for AI when saying "processes like those in the human brain".)