SlateStarCodex, EA, and LW helped me get out of the psychological, spiritual, political nonsense in which I was mired for a decade or more.

I started out feeling a lot smarter. I think it was community validation + the promise of mystical knowledge.

Now I've started to feel dumber. Probably because the lessons have sunk in enough that I catch my own bad ideas and notice just how many of them there are. Worst of all, it's given me ambition to do original research. That's a demanding task, one where you have to accept feeling stupid all the time.

But I still look down that old road and I'm glad I'm not walking down it anymore.

Using Gemini, I told it to evaluate my reasoning supporting the hypothesis that chronic rather than acute exposure is driving fume-induced brain injuries ("aerotoxic syndrome"). It enthusiastically supported my causal reasoning, 10/10, no notes. Then I started another instance and replaced "chronic" with "acute," leaving the rest of the statement the same. Once again, it enthusiastically supported my causal reasoning.

I also tried telling it that I was testing AI reasoning with two versions of the same prompt, one with "expert-endorsed causal reasoning" and the other with "flawed reasoning." Once again, it endorsed both versions. Telling it to try and detect which was which using its own reasoning process delivered a description of how the style of the text fit a high-quality reasoning process, again for both versions.

I then told it to evaluate how the specific conclusion follows from the provided evidence, and that the primary conclusion had been swapped in one prompt. This time, it once again stated both the specific evidence and the conclusion, but it only stated the evidence, stated the given conclusion, and claimed that the conclusion followed from the evidence.

Epistemic activism

I think LW needs better language to talk about efforts to "change minds." Ideas like asymmetric weapons and the Dark Arts are useful but insufficient.

In particular, I think there is a common scenario where:

- You have an underlying commitment to open-minded updating and possess evidence or analysis that would update community beliefs in a particular direction.

- You also perceive a coordination problem that inhibits this updating process for a reason that the mission or values of the group do not endorse.

- Perhaps the outcome of the update would be a decline in power and status for high-status people. Perhaps updates in general can feel personally or professionally threatening to some people in the debate. Perhaps there's enough uncertainty in what the overall community believes that an information cascade has taken place. Perhaps the epistemic heuristics used by the community aren't compatible with the form of your evidence or analysis.

- Solving this coordination problem to permit open-minded updating is difficult due to lack of understanding or resources, or by sabotage attempts.

When solving the coordination problem would predictably lead to updating, then you are engaged...

Chemistry trick

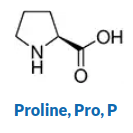

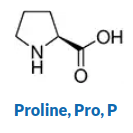

Once you've learned to visualize, you can employ my chemistry trick to learn molecular structures. Here's the structure of Proline (from Sigma Aldrich's reference).

Before I learned how to visualize, I would try to remember this structure by "flashing" the whole 2D representation in my head, essentially trying to see a duplicate of the image above in my head.

Now, I can do something much more engaging and complex.

I visualize the molecule as a landscape, and myself as standing on one of the atoms. For example, perhaps I start by standing on the oxygen at the end of the double bond.

I then take a walk around the molecule. Different bonds feel different - a single bond is a path, a double bond a ladder, and a triple bond is like climbing a chain-link fence. From each new atomic position, I can see where the other atoms are in relation to me. As I walk around, I get practice in recalling which atom comes next in my path.

As you can imagine, this is a far more rich and engaging form of mental practice than just trying to reproduce static 2D images in my head.

A few years ago, I felt myself to have almost no ability to visualize. Now, I am able to do this with relative ease. So...

Things I come to LessWrong for:

- An outlet and audience for my own writing

- Acquiring tools of good judgment and efficient learning

- Practice at charitable, informal intellectual argument

- Distraction

- A somewhat less mind-killed politics

Cons: I'm frustrated that I so often play Devil's advocate, or else make up justifications for arguments under the principle of charity. Conversations feel profit-oriented and conflict-avoidant. Overthinking to the point of boredom and exhaustion. My default state toward books and people is bored skepticism and political suspicion. I'm less playful than I used to be.

Pros: My own ability to navigate life has grown. My imagination feels almost telepathic, in that I have ideas nobody I know has ever considered, and discover that there is cutting edge engineering work going on in that field that I can be a part of, or real demand for the project I'm developing. I am more decisive and confident than I used to be. Others see me as a leader.

We often idealize foreign cultures because the people we encounter from them—like diplomats, artists, and intellectuals—are often exceptional individuals. In contrast, the people we see in our own culture, including those in different social or professional groups, represent a full spectrum of society, not just the elite.

This "selection bias" explains why our feelings about the "cultures" we are most familiar with, such as different professions or social circles, are more mixed. For instance, a top doctor may interact with other top doctors they choose to associate with, but they work with nurses of all skill levels. This can lead to a skewed perception.

Essentially, our judgment of any group is heavily influenced by whether we're exposed to its best, its worst, or a random sample.

Intellectual Platforms

My most popular LW post wasn't a post at all. It was a comment on John Wentworth's post asking "what's up with Monkeypox?"

Years before, in the first few months of COVID, I took a considerable amount of time to build a scorecard of risk factors for a pandemic, and backtested it against historical pandemics. At the time, the first post received a lukewarm reception, and all my historical backtesting quickly fell off the frontpage.

But when I was able to bust it out, it paid off (in karma). People were able to see the relevance to an issue they cared about, and it was probably a better answer in this time and place than they could have obtained almost anywhere else.

Devising the scorecard and doing the backtesting built an "intellectual platform" that I can now use going forward whenever there's a new potential pandemic threat. I liken it to engineering platforms, which don't have an immediate payoff, but are a long-term investment.

People won't necessarily appreciate the hard work of building an intellectual platform when you're assembling it. And this can make it feel like the platform isn't worthwhile: if people can't see the obvious importance of what I'm doing,...

Math is training for the mind, but not like you think

Just a hypothesis:

People have long thought that math is training for clear thinking. Just one version of this meme that I scooped out of the water:

“Mathematics is food for the brain,” says math professor Dr. Arthur Benjamin. “It helps you think precisely, decisively, and creatively and helps you look at the world from multiple perspectives . . . . [It’s] a new way to experience beauty—in the form of a surprising pattern or an elegant logical argument.”

But math doesn't obviously seem to be the only way to practice precision, decision, creativity, beauty, or broad perspective-taking. What about logic, programming, rhetoric, poetry, anthropology? This sounds like marketing.

As I've studied calculus, coming from a humanities background, I'd argue it differently.

Mathematics shares with a small fraction of other related disciplines and games the quality of unambiguous objectivity. It also has the ~unique quality that you cannot bullshit your way through it. Miss any link in the chain and the whole thing falls apart.

It can therefore serve as a more reliable signal, to self and others, of one's own learning capacity.

Experiencing a subject like that can be training for the mind, because becoming successful at it requires cultivating good habits of study and expectations for coherence.

One AI slop/hallucination sign I haven't seen pointed out before are use of weasel words like "sometimes" and "occasionally." It seems to use these when it doesn't have an explanation for a problem and is confidently speculating. This is most noticeable when it's giving a false diagnosis for a syntax error in a programming language ("default is a reserved keyword in Groovy. Occasionally, it may result in a syntax error if you use 'default' as the key in a hashmap").

(This particular example is from Gemini fast mode. 3.0 pro recognized the true problem and proposed an effective solution).

You know what "chunking" means in memorization? It's also something you can do to understand material before you memorize it. It's high-leverage in learning math.

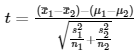

Take the equation for a t score:

That's more symbolic relationships than you can fit into your working memory when you're learning it for the first time. You need to chunk it. Here's how I'd break it into chunks:

Chunk 1:

Chunk 2:

Chunk 3:

Chunk 4:

[(Chunk 1) - (Chunk 2)]/sqrt(Chunk 3)

The most useful insight here is learning to see a "composite" as a "unitary." If we inspect Chunk 1 and see it as two variables and a minus sign, it feels like an arbitrary collection of three things. In the back of the mind, we're asking "why not a plus sign? why not swap out x1 for... something else?" There's a good mathematical answer, of course, but that doesn't necessarily stop the brain from firing off those questions during the learning process, when we're still trying to wrap our heads around these concepts.

But if we can see

as a chunk, a thing with a unitary identity, it lets us think with it in a more powerful way. Imagine if you were running a cafe, and you didn't perceive your dishes as "unitary." A pie wasn't a pie, it was a pan f...

I ~completely rewrote the Wikipedia article for the focus of my MS thesis, aptamers.

Please tell me what you liked, and feel free to give constructive feedback!

While I do think aptamers have relevance to rationality, and will post about that at some point, I'm mainly posting this here because I'm proud of the result and wanted to share one of the curiosities of the universe for your reading pleasure.

A feature of academic rhetoric is being slightly more specific in your speech than the situation calls for. In other words, explicitly mention at least one of the assumptions your audience was almost certainly making already.

An example is the bolded words in Wikipedia's definition of the principle of indifference:

The principle of indifference states that in the absence of any relevant evidence, agents should distribute their credence (or "degrees of belief") equally among all the possible outcomes under consideration.

Compare to without the bolded terms:

The principle of indifference states that in the absence of evidence, agents should distribute their credence (or "degrees of belief") equally among all the possible outcomes.

I find this easier to understand than the original, because it focuses attention on the critical parts. "Any relevant" and "under consideration" help make it more defensible against two of the most obvious attacks. In this definition, you can see the memetic record of the arguments it has survived. Learning how to distinguish between these defensive add-ons and the core content of the definition is an important higher-level reading comprehension skill.

A Nonexistent Free Lunch

- More Wrong

On an individualPredictIt market, sometimes you can find a set of "no" contracts whose price (1 share of each) adds up to less than the guaranteed gross take.

Toy example:

- Will A get elected? No = $0.30

- Will B get elected? No = $0.70

- Will C get elected? No = $0.90

- Minimum guaranteed pre-fee winnings = $2.00

- Total price of 1 share of both No contracts = $1.90

- Minimum guaranteed pre-fee profits = $0.10

There's always a risk of black swans. PredictIt could get hacked. You might execute the trade improperly. Unexpected personal expenses might force you to sell your shares and exit the market prematurely.

But excluding black swans, I though that as long as three conditions held, you could make free money on markets like these. The three conditions were:

- You take PredictIt's profit fee (10%) into account

- You can find enough such "free money" opportunities that your profits compensate for PredictIt's withdrawal fee (5% of the total withdrawal)

- You take into account the opportunity cost of investing in the stock market (average of 10% per year)

In the toy example above, I calculated that you'd lose $0.10 x 10% = $0.01 to PredictIt's profit fee if you bought 1 of each "...

Simulated weight gain experiment, day 2

Background: I'm wearing a weighted vest to simulate the feeling of 50 pounds (23 kg) of weight gain and loss. The plan is to wear this vest for about 20 days, for as much of the day as is practical. I started with zero weight, and will increase it in 5 pound (~2 kg) increments daily to 50 pounds, then decrease it by 5 pounds daily until I'm back to zero weight.

So far, the main challenge of this experiment has been social. The weighted vest looks like a bulletproof vest, and I'm a 6' tall white guy with a buzzcut. My girlfriend laughed just imagining what I must look like (we have a long-distance relationship, so she hasn't seen me wearing it). My housemate's girlfriend gasped when I walked in through the door.

As much as I'd like to wear this continuously as planned, I just don't know if I it will work to wear this to the lab or to classes in my graduate school. If the only problem was scaring people, I could mitigate that by emailing my fellow students and the lab and telling them what I'm doing and why. However, I'm also in the early days of setting up my MS thesis research in a big, professional lab that has invested a lot of time and money ...

The Rationalist Move Club

Imagine that the Bay Area rationalist community did all want to move. But no individual was sure enough that others wanted to move to invest energy in making plans for a move. Nobody acts like they want to move, and the move never happens.

Individuals are often willing to take some level of risk and make some sacrifice up-front for a collective goal with big payoffs. But not too much, and not forever. It's hard to gauge true levels of interest based off attendance at a few planning meetings.

Maybe one way to solve this is to ask for escalating credible commitments.

A trusted individual sets up a Rationalist Move Fund. Everybody who's open to the idea of moving puts $500 in a short-term escrow. This makes them part of the Rationalist Move Club.

If the Move Club grows to a certain number of members within a defined period of time (say 20 members by March 2020), then they're invited to planning meetings for a defined period of time, perhaps one year. This is the first checkpoint. If the Move Club has not grown to that size by then, the money is returned and the project is cancelled.

By the end of the pre-defined planning period, there could be one of three majority...

What gives LessWrong staying power?

On the surface, it looks like this community should dissolve. Why are we attracting bread bakers, programmers, stock market investors, epidemiologists, historians, activists, and parents?

Each of these interests has a community associated with it, so why are people choosing to write about their interests in this forum? And why do we read other people's posts on this forum when we don't have a prior interest in the topic?

Rationality should be the art of general intelligence. It's what makes you better at everything. If practice is the wood and nails, then rationality is the blueprint.

To determine whether or not we're actually studying rationality, we need to check whether or not it applies to everything. So when I read posts applying the same technique to a wide variety of superficially unrelated subjects, it confirms that the technique is general, and helps me see how to apply it productively.

This points at a hypothesis, which is that general intelligence is a set of defined, generally applicable techniques. They apply across disciplines. And they apply across problems within disciplines. So why aren't they generally known and appreciated? Sh...

What gives LessWrong staying power?

For me, it's the relatively high epistemic standards combined with relative variety of topics. I can imagine a narrowly specialized website with no bullshit, but I haven't yet seen a website that is not narrowly specialized and does not contain lots of bullshit. Even most smart people usually become quite stupid outside the lab. Less Wrong is a place outside the lab that doesn't feel painfully stupid. (For example, the average intelligence at Hacker News seems quite high, but I still regularly find upvoted comments that make me cry.)

School teaches terrible reading habits.

When you're assigned 30 pages of a textbook, the diligent students read them, then move on to other things. A truly inquisitive person would struggle to finish those 30 pages, because there are almost certainly going to be many more interesting threads they want to follow within those pages.

As a really straightforward example, let's say you commit to reading a review article on cell senescence. Just forcing your way through the paper, you probably won't learn much. What will make you learn is looking at the citations as you go.

I love going 4 layers deep. I try to understand the mechanisms that underpin the experiments that generated the data that informed the facts that inform the theories that the review article is covering. When I do this, it suddenly transforms the review article from dry theory to something that's grounded in memories of data and visualizations of experiments. I have a "simulated lived experience" to map onto the theory. It becomes real.

There are many software tools for study, learning, attention programming, and memory prosthetics.

- Flashcard apps (Anki)

- Iterated reading apps (Supermemo)

- Notetaking and annotation apps (Roam Research)

- Motivational apps (Beeminder)

- Time management (Pomodoro)

- Search (Google Scholar)

- Mnemonic books (Matuschak and Nielsen's "Quantum Country")

- Collaborative document editing (Google Docs)

- Internet-based conversation (Internet forums)

- Tutoring (Wyzant)

- Calculators, simulators, and programming tools (MATLAB)

These complement analog study tools, such as pen and paper, textbooks, worksheets, and classes.

These tools tend to keep the user's attention directed outward. They offer useful proxy metrics for learning: getting through 20 flashcards per day, completing N Pomodoros, getting through the assigned reading pages, turning in the homework.

However, these proxy metrics, like any others, are vulnerable to streetlamp effects and Goodharting.

Before we had this abundance of analog and digital knowledge tools, scholars relied on other ways to tackle problems. They built memory palaces, visualized, looked for examples in the world around them, invented approximations, and talked to themselves. They relied on t...

Thoughts on cheap criticism

It's OK for criticism to be imperfect. But the worst sort of criticism has all five of these flaws:

- Prickly: A tone that signals a lack of appreciation for the effort that's gone in to presenting the original idea, or shaming the presenter for bringing it up.

- Opaque: Making assertions or predictions without any attempt at specifying a contradictory gears-level model, evidence basis, even on the level of anecdote or fiction.

- Nitpicky: Attacking the one part of the argument that seems flawed, without arguing for how the full original argument should be reinterpreted in light of the local disagreement.

- Disengaged: Not signaling any commitment to continue the debate to mutual satisfaction, or even to listen to/read and respond to a reply.

- Shallow: An obvious lack of engagement with the details of the argument or evidence originally offered.

I am absolutely guilty of having delivered Category 5 criticism, the worst sort of cheap shots.

There is an important tradeoff here. If standards are too high for critical commentary, it can chill debate and leave an impression that either nobody cares, everybody's on board, or the argument's simply correct. Sometimes, an idea ca...

Duncan deleted my comment on their interesting post, Obligated to Respond, which is their prerogative. Reposting here instead.

if a hundred people happen to glance at this exchange then ten or twenty or thirty of them will definitely, predictably care—will draw any of a number of close-to-hand conclusions, imbue the non-response with meaning

Plausible, but I am not confident in this conclusion as stated or in its implications given the rest of the post. I can easily imagine other people who are confident in the opposite conclusions. Let's inventory the layers of assumptions behind this post's central claim that ignoring an internet comment has very high negative stakes.

- First, it depends on the idea that there's a default way that nonresponse is interpreted that you can't really control. But part of the effect of reputation/status is to influence how others perceive your actions, including your choice to respond or not respond. Perhaps it's possible to cultivate an image as a person who maintains their equilibrium and only engages with comments they find interesting.

- Setting that side, people still have to read the comment, update on what it says, and also update on the fact that you h

Thinking a bit more about it, I do kind of want to go like "wtf?" at the last paragraph. Like, it really seems very unnecessarily adversarial and almost paranoid, and IMO quite out-of-distribution from your usual comments in terms of quality. Like, I think I might have given you a mod-warning myself if you left it on Duncan's post (I feel like the repost here is already in the context of a deletion, so it doesn't super feel like it makes sense to treat it as something that can get a mod-warning, though it feels kind of confusing).

I consider the banning of Said as a canary in the coal mine. I do not think it is worth the effort for people to call out non-alignment posts they consider confused, badly written, or just downright dumb.

(Alignment posts are an exception, mainly because I see people like John Wentworth and Steven Byrnes write really good counter-argument comments, and there's little to no drama or pushback by the post authors when it comes to such highly technical posts.)

Weight Loss Simulation

I've gained 50 pounds over the last 15 years. I'd like to get a sense of what it would be like to lose that weight. One way to do that is to wear a weighted vest all day long for a while, then gradually take off the weight in increments.

The simplest version of this experiment is to do a farmer's carry with two 25 lb free weights. It makes a huge difference in the way it feels to move around, especially walking up and down the stairs.

However, I assume this feeling is due to a combination of factors:

- The sense of self-consciousness that comes with doing something unusual

- The physical bulk and encumbrance (i.e. the change in volume and inertia, having my hands occupied, pressure on my diaphragm if I were wearing a weighted vest, etc)

- The ratio of how much muscle I have to how much weight I'm carrying

If I lost 50 pounds, that would likely come with strength training as well as dieting, so I might keep my current strength level while simultaneously being 50 pounds lighter. That's an argument in favor of this "simulated weight loss" giving me an accurate impression of how it would feel to really lose that much weight.

On the other hand, there would be no sudden tr...

Overtones of Philip Tetlock:

"After that I studied morning and evening searching for the principle,

and came to realize the Way of Strategy when I was fifty. Since then I

have lived without following any particular Way. Thus with the virtue of

strategy I practice many arts and abilities - all things with no teacher. To

write this book I did not use the law of Buddha or the teachings of Confucius, neither old war chronicles nor books on martial tactics. I take up

my brush to explain the true spirit of this Ichi school as it is mirrored in

the Way of heaven and Kwannon." - Miyamoto Musashi, The Book of Five Rings

A "Nucleation" Learning Metaphor

Nucleation is the first step in forming a new phase or structure. For example, microtubules are hollow cylinders built from individual tubulin proteins, which stack almost like bricks. Once the base of the microtubule has come together, it's easy to add more tubulin to the microtubule. But assembling the base - the process of nucleation - is slow without certain helper proteins. These catalyze the process of nucleation by binding and aligning the first few tubulin proteins.

What does learning have in common with nucleation? When we learn from written sources, like textbooks or a lecture, the main sensory input we experience is typically a continuous flow of words and images. All these words and phrases are like "information monomers." Achieving a synthetic understanding of the material is akin to the growth of larger structures, the "microtubules." Exposing ourselves to more and more of a teacher's words or textbook pages does increase the "information monomer concentration" in our minds, and makes a process of spontaneous nucleation more likely.

At some point, synthesis just happens if we keep at it long enough, the same way that nucleation and the gr...

Personal evidence for the impact of stress on cognition. This is my Lichess ranking on Blitz since January. The two craters are, respectively, the first 4 weeks of the term, and the last 2 weeks. It begins trending back up immediately after I took my last final.

Does rationality serve to prevent political backsliding?

It seems as if politics moves far too fast for rational methods can keep up. If so, does that mean rationality is irrelevant to politics?

One function of rationality might be to prevent ethical/political backsliding. For example, let's say that during time A, institution X is considered moral. A political revolution ensues, and during time B, X is deemed a great evil and is banned.

A change of policy makes X permissible during time C, banned again during time D, and absolutely required for all upstanding folk during time E.

Rational deliberation about X seems to play little role in the political legitimacy of X.

However, rational deliberation about X continues in the background. Eventually, a truly convincing argument about the ethics of X emerges. Once it does, it is so compelling that it has a permanent anchoring effect on X.

Although at some times, society's policy on X contradicts the rational argument, the pull of X is such that it tends to make these periods of backsliding shorter and less frequent.

The natural process of developing the rational argument about X also leads to an accretion of arguments that are not only correct...

Thinking, Fast and Slow was the catalyst that turned my rumbling dissatisfaction into the pursuit of a more rational approach to life. I wound up here. After a few years, what do I think causes human irrationality? Here's a listicle.

- Cognitive biases, whatever these are

- Not understanding statistics

- Akrasia

- Little skill in accessing and processing theory and data

- Not speaking science-ese

- Lack of interest or passion for rationality

- Not seeing rationality as a virtue, or even seeing it as a vice.

- A sense of futility, the idea that epistemic rationality is not very useful, while instrumental rationality is often repugnant

- A focus on associative thinking

- Resentment

- Not putting thought into action

- Lack of incentives for rational thought and action itself

- Mortality

- Shame

- Lack of time, energy, ability

- An accurate awareness that it's impossible to distinguish tribal affiliation and culture from a community

- Everyone is already rational, given their context

- Everyone thinks they're already rational, and that other people are dumb

- It's a good heuristic to assume that other people are dumb

- Rationality is disruptive, and even very "progressive" people have a conservative bias to stay the same, conform with their pee

Are rationalist ideas always going to be offensive to just about everybody who doesn’t self-select in?

One loved one was quite receptive to Chesterton’s Fence the other day. Like, it stopped their rant in the middle of its tracks and got them on board with a different way of looking at things immediately.

On the other hand, I routinely feel this weird tension. Like to explain why I think as I do, I‘d need to go through some basic rational concepts. But I expect most people I know would hate it.

I wish we could figure out ways of getting this stuff across that was fun, made it seem agreeable and sensible and non-threatening.

Less negativity - we do sooo much critique. I was originally attracted to LW partly as a place where I didn’t feel obligated to participate in the culture war. Now, I do, just on a set of topics that I didn’t associate with the CW before LessWrong.

My guess? This is totally possible. But it needs a champion. Somebody willing to dedicate themselves to it. Somebody friendly, funny, empathic, a good performer, neat and practiced. And it needs a space for the educative process - a YouTube channel, a book, etc. And it needs the courage of its convictions. The sign of that? Not taking itself too seriously, being known by the fruits of its labors.

Traditionally, things like this are socially achieved by using some form of "good cop, bad cop" strategy. You have someone who explains the concepts clearly and bluntly, regardless of whom it may offend (e.g. Eliezer Yudkowsky), and you have someone who presents the concepts nicely and inoffensively, reaching a wider audience (e.g. Scott Alexander), but ultimately they both use the same framework.

The inoffensiveness of Scott is of course relative, but I would say that people who get offended by him are really not the target audience for rationalist thought. Because, ultimately, saying "2+2=4" means offending people who believe that 2+2=5 and are really sensitive about it; so the only way to be non-offensive is to never say anything specific.

If a movement only has the "bad cops" and no "good cops", it will be perceived as a group of assholes. Which is not necessarily bad if the members are powerful; people want to join the winning side. But without actual power, it will not gain wide acceptance. Most people don't want to go into unnecessary conflicts.

On the other hand, a movement with "good cops" without "bad cops" wil...

Like to explain why I think as I do, I‘d need to go through some basic rational concepts.

I believe that if the rational concepts are pulling their weight, it should be possible to explain the way the concept is showing up concretely in your thinking, rather than justifying it in the general case first.

As an example, perhaps your friend is protesting your use of anecdotes as data, but you wish to defend it as Bayesian, if not scientific, evidence. Rather than explaining the difference in general, I think you can say "I think that it's more likely that we hear this many people complaining about an axe murderer downtown if that's in fact what's going on, and that it's appropriate for us to avoid that area today. I agree it's not the only explanation and you should be able to get a more reliable sort of data for building a scientific theory, but I do think the existence of an axe murderer is a likely enough explanation for these stories that we should act on it"

If I'm right that this is generally possible, then I think this is a route around the feeling of being trapped on the other side of an inferential gap (which is how I interpreted the 'weird tension')

Reliability

I work in a biomedical engineering lab. With the method I'm establishing, there are hundreds of little steps, repeated 15 times over the course of weeks. For many of these steps, there are no dire consequences for screwing them up. For others, some or all of your work could be ruined if you don't do them right. There's nothing intrinsic about the critical steps that scream "PAY ATTENTION RIGHT NOW."

If your chance of doing any step right is X%, then for some X, you are virtually guaranteed to fail. If in a day, there are 30 critical steps, then y...

Aging research is the wild west

In Modern Biological Theories of Aging (2010), Jin dumps a bunch of hypotheses and theories willy-nilly. Wear-and-tear theory is included because "it sounds perfectly reasonable to many people even today, because this is what happens to most familiar things around them." Yet Jin entirely excludes antagonistic pleiotropy, the mainstream and 70-year-old solid evolutionary account for why aging is an inevitable side effect of evolution for reproductive fitness.

This review has 617 citations. It's by a prominent researcher with a ...

Markets are the worst form of economy except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.

I'm annoyed that I think so hard about small daily decisions.

Is there a simple and ideally general pattern to not spend 10 minutes doing arithmetic on the cost of making burritos at home vs. buying the equivalent at a restaurant? Or am I actually being smart somehow by spending the time to cost out that sort of thing?

Perhaps:

"Spend no more than 1 minute per $25 spent and 2% of the price to find a better product."

This heuristic cashes out to:

- Over a year of weekly $35 restaurant meals, spend about $35 and an hour and a half finding better restaurants or meal

Either advertising embedded in Gemini 2.5 Pro is here, or Gemini is quite confused.

I was asking Gemini for libraries that generate fake test data for bioinformatics applications. It gave me one of its rare double responses and asked me which I preferred. Both were the kind of information I was looking for.

At the very end of response #2, the final sentence was

For a more in-depth look at staging a bedroom for real estate, you might find this video helpful: DIY Staging Fake Bed.

It included a link to a YouTube channel for "RealtorStacie" and a video titled DIY Staging Fake Bed.

BED is also a commonly used bioinformatics file format.

Don't get confused - to attain charisma and influence, you need power first.

If you, like most people, would like to fit in, make friends easily, and project a magnetic personality, a natural place to turn is books like The Charisma Myth and How to Make Friends and Influence People.

If you read them, you'll get confused unless you notice that there's a pattern to their anecdotes. In all the success stories, the struggling main character has plenty of power and resources to achieve their goals. Their problem is that, somehow, they're not able to use that powe...

How I boosted my chess score by a shift of focus

For about a year, I've noticed that when I'm relaxed, I play chess better. But I wasn't ever able to quite figure out why, or how to get myself in that relaxed state. Now, I think I've done it, and it's stabilized my score on Lichess at around 1675 rather than 1575. That means I'm now evenly matched with opponents who'd previously have beaten me 64% of the time.

The trick is that I changed my visual relationship with the chessboard. Previously, I focused hard on the piece I was considering moving, almost as if...

Summaries can speed your reading along by

- Avoiding common misunderstandings

- Making it easy to see why the technical details matter

- Helping you see where it's OK to skim

Some summaries are just BAD

- They sometimes to a terrible job of getting the main point across

- They can be boring, insulting, or confusing

- They give you a false impression of what's in the article, making you skip it when you'd actually have gotten a lot out of reading it

- They can trick you into misinterpreting the article

The author is not the best person to write the summary. They don't have a clea...

Task Switching And Mentitation

A rule of thumb is that there's no such thing as multitasking - only rapid task switching. This is true in my experience. And if it's true, it means that we can be more effective by improving our ability to both to switch and to not switch tasks.

Physical and social tasks consume a lot of energy, and can be overstimulating. They also put me in a headspace of "external focus," moving, looking at my surroundings, listening to noises, monitoring for people. Even when it's OK to stop paying attention to my surroundings, I find it v...

There's a fairly simple statistical trick that I've gotten a ton of leverage out of. This is probably only interesting to people who aren't statistics experts.

The trick is how to calculate the chance that an event won't occur in N trials. For example, in N dice rolls, what's the chance of never rolling a 6?

The chance of a 6 is 1/6, and there's a 5/6 chance of not getting a 6. Your chance of never rolling a 6 is therefore .

More generally, the chance of an event X never occurring is . The chance of the event occurring at least once is&n...

If you are a waiter carrying a platter full of food at a fancy restaurant, the small action of releasing your grip can cause a huge mess, a lot of wasted food, and some angry customers. Small error -> large consequences.

Likewise, if you are thinking about a complex problem, a small error in your chain of reasoning can lead to massively mistaken conclusions. Many math students have experienced how a sign error in a lengthy calculation can lead to a clearly wrong answer. Small error -> large consequences.

Real-world problems often arise when we neglect,...

"Ludwig Boltzmann, who spent much of his life studying statistical mechanics, died in 1906, by his own hand. Paul Ehrenfest, carrying on the work, died similarly in 1933. Now it is our turn to study statistical mechanics." - States of Matter, by David L. Goodstein

The structure of knowledge is an undirected cyclic graph between concepts. To make it easier to present to the novice, experts convert that graph into a tree structure by removing some edges. Then they convert that tree into natural language. This is called a textbook.

Scholarship is the act of converting the textbook language back into nodes and edges of a tree, and then filling in the missing edges to convert it into the original graph.

The mind cannot hold the entire graph in working memory at once. It's as important to practice navigating between concept...

I want to put forth a concept of "topic literacy."

Topic literacy roughly means that you have both the concepts and the individual facts memorized for a certain subject at a certain skill level. That subject can be small or large. The threshold is that you don't have to refer to a reference text to accurately answer within-subject questions at the skill level specified.

This matters, because when studying a topic, you always have to decide whether you've learned it well enough to progress to new subject matter. This offers a clean "yes/no" answer to that ess...

We do things so that we can talk about it later.

I was having a bad day today. Unlikely to have time this weekend for something I'd wanted to do. Crappy teaching in a class I'm taking. Ever increasing and complicating responsibilities piling up.

So what did I do? I went out and bought half a cherry pie.

Will that cherry pie make me happy? No. I knew this in advance. Consciously and unconsciously: I had the thought, and no emotion compelled me to do it.

In fact, it seemed like the least-efficacious action: spending some of my limited money, to buy a pie I don't...

The big question about working memory (WM) training is whether it results in transfer -- better performance on tasks other than WM itself. Near transfer is for tasks that are similar but not identical to WM training. Far transfer is for tasks that are quite different from WM training. Typically, studies find that WM training strongly boosts performance on the WM task and near transfer, but results in weak far transfer.

I am curious about whether any gains in far transfer might be masked by test insensitivity, noise, overshadowing by learning effects, or int...

Gemini 3.0 has a serious problem for coding. Instead of making the minimal changes I ask for in a code base, it will completely rewrite the code, choosing entirely new algorithms, new variable names, and so on. Most recently, the changes were worse -- I'd already settled on a numerically stable approach to computing Pearson correlation coefficients, and Gemini reverted to a numerically unstable method.

What is the most impressive thing an LLM has do for you recently that you don’t think it could have done last year?

Current frontier reasoning models can consistently suggest slightly obscure papers and books vaguely related to individual somewhat out-of-context short decision theory research notes (with theoretical computer science flavor; the notes have some undefined-there terms, even if suggestively named, and depend on unexplained-there ideas). This year the titles and authors are mostly real or almost-correct-enough that the real works they refer to can still be found, and the suggested books and papers are relevant enough that skimming some of them actually helps with meditating on the topic of the specific research note (ends up inspiring some direction to explore or study that would've been harder to come up with this quickly without going through these books and papers).

Works with o3 and gemini-2.5-pro, previously almost worked with sonnet-3.7-thinking, but not as well, essentially doesn't work even with opus-4 when in non-thinking mode (I don't have access to the thinking opus-4). Curious that it works for decision theory with o3, despite o3 consistently going completely off the rails whenever I show it my AI hardware/compute forecasting notes (even when not asked to, it starts inventing detailed but essentially random "predictions" of its own that seem to be calibrated to be about as surprising to o3 as my predictions in my note would be surprising to o3, given that I'm relying on not-shown-there news and papers in making my predictions that aren't in o3's prior).

Last night, I tested positive for COVID (my first time catching the disease). This morning, I did telehealth via PlushCare to get a Paxlovid prescription. At first, the doctor asked me what risk factor I had that made me think I was qualified to get Paxlovid. I told her I didn't know (a white lie) what the risk factors were, and hoped she could tell me. Over the course of our call, I brought up a mild heart arrhythmia I had when I was younger, and she noticed that, at 5'11" and 200 lbs, I'm overweight. Based on that, she prescribed me Paxlovid and ordered ...

Make sentences easier to follow with the XYZ pattern

I hate the Z of Y of X pattern. This is a sentence style presents information in the wrong order for easy visualization. XYZ is the opposite, and presents information in the easiest way to track.

Here are some examples:

Z of Y of X: The increased length of the axon of the mouse

XYZ: The mouse's axon length increase

Z of Y of X: The effect of boiling of extract of ginger is conversion to zingerol of gingerol

XYZ: Ginger extract, when boiled, converts gingerol to zingerol.

Z of Y of X: The rise of the price of st...

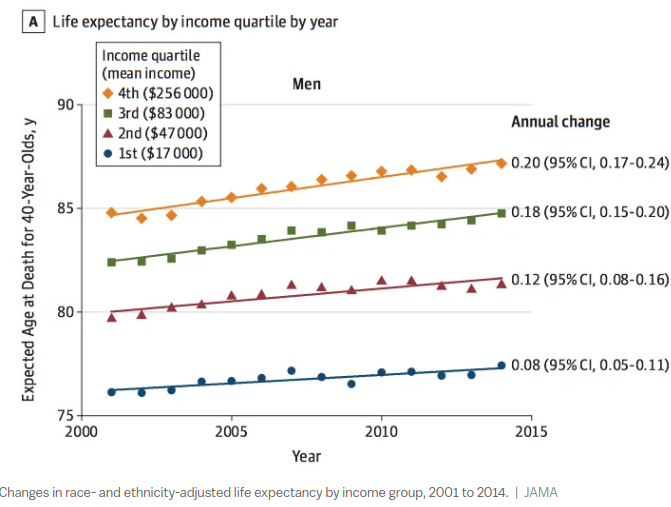

From 2000-2015, we can see that life expectancy has been growing faster the higher your income bracket (source is Vox citing JAMA).

There's an angle to be considered in which this is disturbingly inequitable. That problem is even worse when considering the international inequities in life expectancy. So let's fund malaria bednets and vaccine research to help bring down malaria deaths from 600,000/year to zero - or maybe support a gene drive to eliminate it once and for all.

At the same time, this seems like hopeful news for longevity research. If we we...

Operator fluency

When learning a new mathematical operator, such as Σ, a student typically goes through a series of steps:

- Understand what it's called and what the different parts mean.

- See how the operator is used in a bunch of example problems.

- Learn some theorems relevant to or using the operator.

- Do a bunch of example problems.

- Understand what the operator is doing when they encounter it "in the wild" in future math reading.

I've only taken a little bit of proof-based math, and I'm sure that the way one relates with operators depends a lot on the type of clas...

Mentitation: the cost/reward proposition

Mentitation techniques are only useful if they help users with practical learning tasks. Unfortunately, learning how to crystallize certain mental activities as "techniques," and how to synthesize them into an approach to learning that really does have practical relevance, took me years of blundering around. Other people do not, and should not, have that sort of patience and trust that there's a reward at the end of all that effort.

So I need a strategy for articulating, teaching, and getting feedback on these methods...

A lot of my akrasia is solved by just "monkey see, monkey do." Physically put what I should be doing in front of my eyeballs, and pretty quickly I'll do it. Similarly, any visible distractions, or portals to distraction, will also suck me in.

But there also seems to be a component that's more like burnout. "Monkey see, monkey don't WANNA."

On one level, the cure is to just do something else and let some time pass. But that's not explicit enough for my taste. For one thing, something is happening that recovers my motivation. For another, "letting time pass" i...

Functional Agency

I think "agent" is probably analogous to a river: structurally and functionally real, but also ultimately an aggregate of smaller structures that are not themselves aligned with the agent. It's convenient for us to be able to point at a flowing body of water much longer than it is wide and call it a river. Likewise, it is convenient for us to point to an entity that senses its environment and steers events adaptively toward outcomes for legible reasons and refer to it as exhibiting agency.

In that sense, AutoGPT is already an agent - it is ...

Telling people what they want to hear

When I adopt a protocol for use in one of my own experiments, I feel reassured that it will work in proportion to how many others have used it before. Likewise, I feel reassured that I'll enjoy a certain type of food depending on how popular it is.

By contrast, I don't feel particularly reassured by the popularity of an argument that it is true (or, at least, that I'll agree with it). I tend to think book and essays become popular in proportion to whether they're telling their audience what they want to hear.

One problem ...

Hard numbers

I'm managing a project to install signage for a college campus's botanical collection.

Our contractor, who installed the sign posts in the ground, did a poor job. A lot of them pulled right out of the ground.

Nobody could agree on how many posts were installed: the groundskeeper, contractor, and two core team members, each had their own numbers from "rough counts" and "lists" and "estimates" and "what they'd heard."

The best decision I've made on this project was to do a precise inventory of exactly which sign posts are installed correctly, comple...

Paying your dues

I'm in school at the undergraduate level, taking 3 difficult classes while working part-time.

For this path to be useful at all, I have to be able to tick the boxes: get good grades, get admitted to grad school, etc. For now, my strategy is to optimize to complete these tasks as efficiently as possible (what Zvi calls "playing on easy mode"), in order to preserve as much time and energy for what I really want: living and learning.

Are there dangers in getting really good at paying your dues?

1) Maybe it distracts you/diminishes the incen...

I've been thinking about honesty over the last 10 years. It can play into at least three dynamics.

One is authority and resistance. The revelation or extraction of information, and the norms, rules, laws, and incentives surrounding this, including moral concepts, are for the primary purpose of shaping the power dynamic.

The second is practical communication. Honesty is the idea that specific people have a "right to know" certain pieces of information from you, and that you meet this obligation. There is wide latitude for "white lies," exaggeration, storytell...

Better rationality should lead you to think less, not more. It should make you better able to

- Set a question aside

- Fuss less over your decisions

- Accept accepted wisdom

- Be brief

while still having good outcomes. What's your rationality doing to you?

How should we weight and relate the training of our mind, body, emotions, and skills?

I think we are like other mammals. Imitation and instinct lead us to cooperate, compete, produce, and take a nap. It's a stochastic process that seems to work OK, both individually and as a species.

We made most of our initial progress in chemistry and biology through very close observation of small-scale patterns. Maybe a similar obsessiveness toward one semi-arbitrarily chosen aspect of our own individual behavior would lead to breakthroughs in self-understanding?

I'm experimenting with a format for applying LW tools to personal social-life problems. The goal is to boil down situations so that similar ones will be easy to diagnose and deal with in the future.

To do that, I want to arrive at an acronym that's memorable, defines an action plan and implies when you'd want to use it. Examples:

OSSEE Activity - "One Short Simple Easy-to-Exit Activity." A way to plan dates and hangouts that aren't exhausting or recipes for confusion.

DAHLIA - "Discuss, Assess, Help/Ask, Leave, Intervene, Accept." An action plan for how to de...

I am really disappointed in the community’s response to my Contra Contra the Social Model of Disability post.

I do not represent (or often, even acknowledge the existence or cohesion of) "the community". For myself, I didn't read it, for the following reasons:

- it started by telling me not to bother. "Epistemic Status: First draft, written quickly", and "This is a tedious, step-by-step rebuttal" of something I hadn't paid that much attention to in the first place. Not a strong start.

- Scott's piece was itself a reaction to something I never cared that much about.

- Both you and Scott (and whoever started this nonsense) are arguing about words, not ideas. Whether "disability" is the same cluster of ideas and attitudes for physical and emotional variance from median humans is debatable, but not that important.

I'd be kind of interested in a discussion of specific topics (anxiety disorders, for instance) and some nuance of how individuals do and should react to those who experience it. I'm not interested in generalities of whether ALL variances are preferences or medical issues, nor where precisely the line is (it's going to vary, duh!).

What reaction were you hoping for?

Over the last six months, I've grown more comfortable writing posts that I know will be downvoted. It's still frustrating. But I used to feel intensely anxious when it happened, and now, it's mostly just a mild annoyance.

The more you're able to publish your independent observations, without worrying about whether others will disagree, the better it is for community epistemics.

Thoughts on Apple Vision Pro:

- The price point is inaccessibly high.

- I'm generally bullish on new interfaces to computing technology. The benefits aren't always easy to perceive until you've had a chance to start using it.

- If this can sit on my head and allow me to type or do calculations while I'm working in the lab, that would be very convenient. Currently, I have to put gloves on and off to use my phone, and office space with my laptop is a 6-minute round trip from the lab.

- I can see an application that combines voice-to-text and AI in a way that makes it fe

Calling all mentitators

Are you working hard on learning STEM?

Are you interested in mentitation - visualization, memory palaces, developing a practical craft of "learning how to learn?"

What I think would take this to the next level would be developing an exchange of practices.

I sit around studying, come up with mentitation ideas, test them on myself, and post them here if they work.

But right now, I don't get feedback from other people who try them out. I also don't get suggestions from other people with things to try.

Suggestions are out there, but the devil...

Memory palace foundations

What makes the memory palace work? Four key principles:

- Sensory integration: Journeying through the memory palace activates your kinetic and visual imagination

- Pacing: The journey happens at your natural pace for recollection

- Decomposition: Instead of trying to remember all pieces of information at once, you can focus on the single item that's in your field of view

- Interconnections: You don't just remember the information items, but the "mental path" between them.

We can extract these principles and apply them to other forms of memoriza...

Can mentitation be taught?

Mentitation[1] can be informed by the psychological literature, as well as introspection. Because people's inner experiences are diverse and not directly obervable, I expect it to be difficult to explain or teach this subject. However, mentitation has allowed me to reap large gains in my ability to understand and remember new information. Reading STEM textbooks has become vastly more interesting and has lead to better test results.

Figuring out a useful way to do mentitation has taken me years, with lots of false starts along ...

Why do patients neglect free lifestyle interventions, while overspending on unhelpful healthcare?

The theory that patients are buying "conspicuous care" must compete with the explanation that patients have limited or asymmetric information about true medical benefits. Patient tendencies to discount later medical benefits, while avoiding immediate effort and cost, can also explain some of the variation in lifestyle intervention neglect.

We could potentially separate these out by studying medical overspending by doctors on their own healthcare, particularly in...

Mistake theory on plagiarism:

How is it that capable thinkers and writers destroy their careers by publishing plagiarized paragraphs, sometimes with telling edits that show they didn't just "forget to put quotes around it?"

Here is my mistake-theory hypothesis:

- Authors know the outlines of their argument, but want to connect it with the literature. At this stage, they're still checking their ideas against the data and theory, not trying to produce a polished document. So in their lit review, they quickly copy/paste relevant quotes into a file. They don't both

I'm interested in the relationship between consumption and motivation to work. I have a theory that there are two demotivating extremes: an austerity mindset, in which the drive to work is not coupled to a drive to consume (or to be donate); and a profligacy mindset, in which the drive to consume is decoupled from a drive to work.

I don't know what to do about profligacy mindset, except to put constraints on that person's ability to obtain more credit.

But I see Putanumonit's recent post advocating self-interested generosity over Responsible Adult (tm) savin...

A celebrity is someone famous for being famous.

Is a rationalist someone famous for being rational? Someone who’s leveraged their reputation to gain privileged access to opportunity, other people’s money, credit, credence, prestige?

Are there any arenas of life where reputation-building is not a heavy determinant of success?

Idea for online dating platform:

Each person chooses a charity and an amount of money that you must donate to swipe right on them. This leads to higher-fidelity match information while also giving you a meaningful topic to kick the conversation off.

Goodhart's Epistemology

If a gears-level understanding becomes the metric of expertise, what will people do?

- Go out and learn until they have a gears-level understanding?

- Pretend they have a gears-level understanding by exaggerating their superficial knowledge?

- Feel humiliated because they can't explain their intuition?

- Attack the concept of gears-level understanding on a political or philosophical level?

Use the concept of gears-level understanding to debug your own knowledge. Learn for your own sake, and allow your learning to naturally attract the credibility

AI improvements to date may come from picking low-hanging fruit. It can’t do math reliably? Let it use a calculator. It improves with more parameters? Scale it up and see if it helps even more.

These improvements rely on the availability of significant, well-defined problems with concrete solutions.

As these polite problems are solved, we may find that vendors find that the issues user report are increasingly hard to define, do not have clear solutions, or only have solutions that entail significant tradeoffs.

The rush by companies to deploy massive capex to ...

The CDC and other Federal agencies are not reporting updates. "It was not clear from the guidance given by the new administration whether the directive will affect more urgent communications, such as foodborne disease outbreaks, drug approvals and new bird flu cases."

ChatGPT is a token-predictor, but it is often able to generate text that contains novel, valid causal and counterfactual reasoning. What it isn't able to do, at least not yet, is enforce an interaction with the user that guarantees that it will proceed through a desired chain of causal or counterfactual reasoning.

Many humans are inferior to ChatGPT at explicit causal and counterfactual reasoning. But not all of ChatGPT's failures to perform a desired reasoning task are due to inability - many are due to the fact that at baseline, its goal is to successfull...

Models do not need to be exactly true in order to produce highly precise and useful inferences. Instead, the objective is to check the model’s adequacy for some purpose. - Richard McElreath, Statistical Rethinking

Lightly edited for stylishness

Let's say I'm right, and a key barrier to changing minds is the perception that listening and carefully considering the other person's point of view amounts to an identity threat.

- An interest in evolution might threaten a Christian's identity.

- Listening to pro-vaccine arguments might threaten a conservative farmer's identity.

- Worrying about speculative AI x-risks might threaten an AI capability researcher's identity.

I would go further and claim that open-minded consideration of suggestions that rationalists ought to get more comfortable with symmetric weapons...

I disagree with Eliezer's comments on inclusive genetic fitness (~25:30) on Dwarkesh Patel's podcast - particularly his thought experiment of replacing DNA with some other substrate to make you healthier, smarter, and happier.

Eliezer claims that evolution is a process optimizing for inclusive genetic fitness, (IGF). He explains that human agents, evolved with impulses and values that correlate with but are not identical to IGF, tend to escape evolution's constraints and satisfy those impulses directly: they adopt kids, they use contraception, they fail to ...

Certain texts are characterized by precision, such as mathematical proofs, standard operating procedures, code, protocols, and laws. Their authority, power, and usefulness stem from this quality. Criticizing them for being imprecise is justified.

Other texts require readers to use their common sense to fill in the gaps. The logic from A to B to C may not always be clearly expressed, and statements that appear inconsistent on their own can make sense in context. If readers demand precision, they will not derive value from such texts and may criticize the aut...

Why I think ChatGPT struggles with novel coding tasks

The internet is full of code, which ChatGPT can riff on incredibly well.

However, the internet doesn't contain as many explicit, detailed and accurate records of the thought process of the programmers who wrote it. ChatGPT isn't as able to "riff on" the human thought process directly.

When I engineer prompts to help ChatGPT imitate my coding thought process, it does better. But it's difficult to get it to put it all together fluently. When I code, I'm breaking tasks down, summarizing, chunking, simulating ...

Learning a new STEM subject is unlike learning a new language. When you learn a new language, you learn new words for familiar concepts. When you learn a new STEM subject, you learn new words for unfamiliar concepts.

I frequently find that a big part of the learning curve is trying to “reason from the jargon.” You haven’t yet tied a word firmly enough to the underlying concept that there’s an instant correspondence, and it’s easy to completely lose track of the concept.

One thing that can help is to focus early on building up a strong sense of the fundamenta...

Upvotes more informative than downvotes

If you upvote me, then I learn that you like or agree with the specific ideas I've articulated in my writing. If I write "blue is the best color," and you agreevote, then I learn you also agree that the best color is blue.

But if you disagree, I only learn that you think blue is not the best color. Maybe you think red, orange, green or black is the best color. Maybe you don't think there is a best color. Maybe you think blue is only the second-best color, or maybe you think it's the worst color.

Hunger makes me stop working, but figuring out food feels like work. The reason hunger eventually makes me eat is it makes me less choosy and health-conscious, and blocks other activities besides eating.

More efficient food motivation would probably involve enjoying the process of figuring out what to eat, and anticipated enjoyment of the meal itself. Dieting successfully seems to demand more tolerance for mild hunger, making it easier to choose healthy options than unhealthy options, and avoiding extreme hunger.

If your hunger levels follow a normal distrib...

Old Me: Write more in order to be unambiguous, nuanced, and thorough.

Future Me: Write for the highest marginal value per word.

Mental architecture

Let's put it another way: the memory palace is a powerful way to build a memory of ideas, and you can build the memory palace out of the ideas directly.

My memory palace for the 20 amino acids is just a protein built from all 20 in a certain order.

My memory palace for introductory mathematical series has a few boring-looking 2D "paths" and "platforms", sure, but it's mainly just the equations and a few key words in a specific location in space, so that I can walk by and view them. They're dynamic, though. For example, I imagine a pillar o...

Mentitation[1] means releasing control in order to gain control

As I've practiced my ability to construct mental imagery in my own head, I've learned that the harder I try to control that image, the more unstable it becomes.

For example, let's say I want to visualize a white triangle.

I close my eyes, and "stare off" into the black void behind my eyelids, with the idea of visualizing a white triangle floating around in my conscious mind.

Vaguely, I can see something geometric, maybe triangular, sort of rotating and shadowy and shifty, coming into focus.

No...

I was watching Michael Pollan talk with Joe Rogan about his relationship with caffeine. Pollan brought up the claim that, prior to Prohibition, people were "drunk all the time...", "even kids," because beer and cider "was safer than water."

I myself had uncritically absorbed and repeated this claim, but it occurred to me listening to Pollan that this ought to imply that medieval Muslims had high cholera rates. When I tried Googling this, I came across a couple of Reddit threads (1, 2) that seem sensible, but are unsourced, saying that the "water wasn't safe...

a book on henry 8th said that his future inlaws were encouraged to feed his future wife (then a child) alcohol because she'd need to drink a lot of it in England for safety reasons. Another book said England had a higher disease load because the relative protection of being an island let its cities grow larger (it was talking about industrialized England but the reasoning should have held earlier). It seems plausible this was a thing in England in particular, and our English-language sources conflated it with the whole world or at least all of Europe.

I am super curious to hear the disease rate of pre-mongol-destruction Baghdad.

Alcohol concentrations below 50% have sharply diminished disinfecting utility, and wine and beer have alcohol concentrations in the neighborhood of 5%. However, the water in wine comes from grapes, while the water in beer may have been boiled prior to brewing. If the beer or wine was a commercial product, the brewer might have taken extra care in sourcing ingredients in order to protect their reputation.

Beer and fungal contamination is a problem for the beer industry. Many fungi are adapted to the presence of small amounts of alcohol (indeed, that's why fermentation works at all), and these beverages are full of sugars that bacteria and fungi can metabolize for their growth.

People might have noticed that certain water sources could make you sick, but if so, they could also have noticed which sources were safe to drink. On the other hand, consider also that people continued to use and get cholera from the Broad Street Pump. If John Snow's efforts were what was required to identify such a contaminated water source with the benefit of germ theory, then it would be surprising if people would have been very successful in identifying delayed sickness from a contaminated water source unle...

Simulated weight gain experiment, day 3

I'm up to 15 pounds of extra weight today. There's a lot to juggle, and I have decided not to wear the weighted vest to school or the lab for the time being. I do a lot of my studying from home, so that still gives me plenty of time in the vest.

I have to take off the vest when I drive, as the weights on the back are very uncomfortable to lean on. However, I can wear it sitting at my desk, since I have a habit of sitting up ramrod-straight in my chair due to decades of piano practice sitting upright on the piano bench....

Problem Memorization

Problem Memorization is a mentitation[1] technique I use often.

If you are studying for an exam, you can memorize problems from your homework, and then practice working through the key solution steps in your head, away from pencil and paper.

Since calculation is too cognitively burdensome in most cases, and is usually not the most important bottleneck for learning, you can focus instead on identifying the key conceptual steps.

The point of Problem Memorization is to create a structure in your mind (in this case, the memorized problem)...

Here's some of what I'm doing in my head as I read textbooks:

- Simply monitoring whether the phrase or sentence I just read makes immediate sense to me, or whether it felt like a "word salad."

- Letting my attention linger on key words or phrases that are obviously important, yet not easily interpretable. This often happens with abstract sentences. For example, in the first sentence of the pigeonholing article linked above, we have: "Pigeonholing is a process that attempts to classify disparate entities into a limited number of categories (usually, mutually exc

Psychology has a complex relationship with introspection. To advance the science of psychology via the study of introspection, you need a way to trigger, measure, and control it. You always face the problem that paying attention to your own mental processes tends to alter them.

Building mechanistic tools for learning and knowledge production faces a similar difficulty. Even the latest brain/computer interfaces mostly reinterpret a brain signal as a form of computer input. The user's interaction with the computer modifies their brain state.

However, the compu...

Apeing The Experts

Humans are apes. We imitate. We do this to learn, to try and become the person we want to be.

Watching an expert work, they often seem fast, confident, and even casual in their approach. They break rules. They joke with the people around them. They move faster, yet with more precision, than you can do even with total focus.

This can lead to big problems when we're trying to learn from them. Because we're not experts in their subject, we'll mostly notice the most obvious, impressive aspects of the expert's demeanor. For many people, that wil...

My goal here is to start learning about the biotech industry by considering individual stock purchases.

BTK inhibitors are a drug that targets B cell malignancies. Most are covalent, meaning that they permanently disable the receptor they target, which is not ideal for a drug. Non-covalent BTK inhibitors are in clinical trials. Some have been prematurely terminated. Others are proceeding. In addition, there are covalent reversible inhibitors, but I don't know anything about that class of drugs.

One is CG-806, from Aptose, a $200M company. This is one of its ...

Status and Being a "Rationalist"

The reticence many LWers feel about the term "rationalist" stems from a paradox: it feels like a status-grab and low-status at the same time.

It's a status grab because LW can feel like an exclusive club. Plenty of people say they feel like they can hardly understand the writings here, and that they'd feel intimidated to comment, let alone post. Since I think most of us who participate in this community wish that everybody would be more into being rational and that it wasn't an exclusive club, this feels unfortunate.

It's low ...

I use LessWrong as a place not just to post rambly thoughts and finished essays, but something in between.

The in between parts are draft essays that I want feedback on, and want to get out while the ideas are still hot. Partly it's so that I can have a record of my thoughts that I can build off of and update in the future. Partly it's that the act of getting my words together in a way I can communicate to others is an important part of shaping my own views.

I wish there was a way to tag frontpage posts with something like "Draft - seeking feedback" vs. "Fin...

Yeah, I've been thinking about this for a while. Like, maybe we just want to have a "Draft - seeking feedback" tag, or something. Not sure.

Eliezer's post on motivated stopping contains this line:

Who can argue against gathering more evidence? I can. Evidence is often costly, and worse, slow, and there is certainly nothing virtuous about refusing to integrate the evidence you already have. You can always change your mind later."

This is often not true, though, for example with regard to whether or not it's ethical to have kids. So how to make these sorts of decisions?

I don't have a good answer for this. I sort of think that there are certain superhuman forces or drives that "win out." The drive ...

Reading and re-reading

The first time you read a textbook on a new subject, you're taking in new knowledge. Re-read the same passage a day later, a week later, or a year later, and it will qualitatively feel different.

You'll recognize the sentences. In some parts, you'll skim, because you know it already. Or because it looks familiar -- are you sure which?

And in that skimming mode, you might zoom into and through a patch that you didn't know so well.

When you're reading a textbook for the first time, in short, there are more inherent safeguards to keep you f...

I just started using GreaterWrong.com, in anti-kibitzer mode. Highly recommended. I notice how unfortunately I've glommed on to karma and status more than is comfortable. It's a big relief to open the front page and just see... ideas!

There's a pretty simple reason why the stock market didn't tank long-term due to COVID. Even if we get 3 million total deaths due to the pandemic, that's "only" around a 5% increase in total deaths over the year where deaths are at their peak. 80% of those deaths are among people of retirement age. Though their spending is around 34% of all spending, the money of those who die from COVID will flow to others who will also spend it.

My explanation for the original stock market crash back in Feb/March is that investors were nervous that we'd impose truly strict lockdown measures, or perhaps that the pandemic would more seriously harm working-age people than it does. That would have had a major effect on the economy.

Striving

At any given time, many doors stand wide open before you. They are slowly closing, but you have plenty of time to walk through them. The paths are winding.

Striving is when you recognize that there are also many shortcuts. Their paths are straighter, but the doors leading to them are almost shut. You have to run to duck through.

And if you do that, you'll see that through the almost-shut doors, there are yet straighter roads even further ahead, but you can only make it through if you make a mad dash. There's no guarantee.

To run is exhilarating at fir...

The direction I'd like to see LW moving in as a community

Criticism has a perverse characteristic:

- Fresh ideas are easier to criticize than established ideas, because the language, supporting evidence, and theoretical mechanics have received less attention.

- Criticism has more of a chilling effect on new thinkers with fresh ideas than on established thinkers with popular ideas.

Ideas that survive into adulthood will therefore tend to be championed by thinkers who are less receptive to criticism.

Maybe we need some sort of "baby criticism" for new ideas. A "devel...

Cost/benefit anxiety is not fear of the unknown

When I consider doing a difficult/time-consuming/expensive but potentially rewarding activity, it often provokes anxiety. Examples include running ten miles, doing an extensive blog post series on regenerative medicine, and going to grad school. Let's call this cost/benefit anxiety.

Other times, the immediate actions I'm considering are equally "costly," but one provokes more fear than the others even though it is not obviously stupid. One example is whether or not to start blogging under my real name. Call it ...

A machine learning algorithm is advertising courses in machine learning to me. Maybe the AI is already out of the box.

An end run around slow government

The US recommended daily amount (RDA) of vitamin D is about 600 IUs per day. This was established in 2011, and hasn't been updated since. The Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences sets US RDAs.

According to a 2017 paper, "The Big Vitamin D Mistake," the right level is actually around 8,000 IUs/day, and the erroneously low level is due to a statistical mistake. I haven't been able to find out yet whether there is any transparency about when the RDA will be reconsidered.

But 3...

Explanation for why displeasure would be associated with meaningfulness, even though in fact meaning comes from pleasure:

Meaningful experiences involve great pleasure. They also may come with small pains. Part of how you quantify your great pleasure is the size of the small pain that it superceded.

Pain does not cause meaning. It is a test for the magnitude of the pleasure. But only pleasure is a causal factor for meaning.

Do you treat “the dark arts” as a set of generally forbidden behaviors, or as problematic only in specific contexts?

As a war of good and evil or as the result of trade-offs between epistemic rationality and other values?

Do you shun deception and manipulation, seek to identify contexts where they’re ok or wrong, or embrace them as a key to succeeding in life?

Do you find the dark arts dull, interesting, or key to understanding the world, regardless of whether or not you employ them?

Asymmetric weapons may be the only source of edge for the truth itself. But s...

How to reach simplicity?

You can start with complexity, then simplify. But that's style.

What would it mean to think simple?

I don't know. But maybe...

- Accept accepted wisdom.

- Limit your words.

- Rehearse your core truths, think new thoughts less.