This matches my impression. FAR could definitely use more funding. Although I'd still at the margin rather hire someone above our bar than e.g. have them earn-to-give and donate to us, the math is getting a lot closer than it used to be, to the point where those with excellent earning potential and limited fit for AI safety might well have more impact pursuing a philanthropic pathway.

I'd also highlight there's a serious lack of diversity in funding. As others in the thread have mentioned, the majority of people's funding comes (directly or indirectly) from OpenPhil. I think OpenPhil does a good job trying to mitigate this (e.g. being careful about power dynamics, giving organizations exit grants if they do decide to stop funding an org, etc) it's ultimately not a healthy dynamic, and OpenPhil appears to be quite capacity constrained in terms of grant evaluation. So, the entry of new funders would help diversify this in addition to increasing total capacity.

One thing I don't see people talk about as much but also seems like a key part of the solution: how can alignment orgs and researchers make more efficient use of existing funding? Spending that was appropriate a year or two ago when funding was plentiful may not be justified any longer, so there's a need to explicitly put in place appropriate budgets and spending controls. There's a fair amount of cost-saving measures I could see the ecosystem implementing that would have limited if any hit on productivity: for example, improved cash management (investing in government money market funds earning ~5% rather than 0% interest checking accounts); negotiating harder with vendors (often possible to get substantial discounts on things like cloud compute or commercial real-estate); and cutting back on some fringe benefits (e.g. more/higher-density open plan rather than private offices). I'm not trying to point fingers here: I've made missteps here as well, for example FAR's cash management currently has significant room for improvement -- we're in the process of fixing this and plan to share a write-up of what we found with other orgs in the next month.

investing in government money market funds earning ~5% rather than 0% interest checking accounts

It’s easier than that—there are high-interest-rate free FDIC-eligible checking accounts. MaxMyInterest.com has a good list, although you might need to be a member to view it. As of this moment (2023-07-20), the top of their leaderboard is: Customers Bank (5.20% APY), BankProv (5.15%), BrioDirect (5.06%), UFB Direct (5.06%).

Thanks, that's a good link. In our case our assets significantly exceed the FDIC $250k insurance limit and there are operational costs to splitting assets across a large number of banks. But a high-interest checking account could be a good option for many small orgs.

our assets significantly exceed the FDIC $250k insurance limit and there are operational costs to splitting assets across a large number of banks

This isn't strictly true: Some "banks" partner with many (real) banks to get greater FDIC coverage. E.g.: Wealthfront has up to $5M FDIC (so I imagine they partner with up to 20 accredited banks).

Re open plan offices: many people find them distracting. I doubt they're a worthwhile cost-saving measure for research-focused orgs; better to have fewer researchers in an environment conducive to deep focus. I could maybe see a business case for them in large orgs where it might be worth sacrificing individual contributors' focus in exchange for more legibility to management, or where management doesn't trust workers to stay on task when no one is hovering over their shoulder, but I hope no alignment org is like that. For many people open plan offices are just great, of course, and I think it can be hard for them to grok how distracting they can be for people on the autism spectrum, to pick a not-so-random example. :) But I like the idea of looking for ways to increase efficiency!

It can definitely be worth spending money when there's a clear case for it improving employee productivity. I will note there are a range of both norms and physical layouts compatible with open-plan, ranging from "everyone screaming at each other and in line of sight" trading floor to "no talking library vibes, desks facing walls with blinders". We've tried to make different open plan spaces zoned with different norms and this has been fairly successful, although I'm sure some people will still be disturbed by even library-style areas and be more productive in a private office.

I'd thought it was a law of nature that quiet norms for open plans don't actually work; it sounds like you've found a way to have your cake and eat it too!

(Speaking just for the Long-Term Future Fund)

It’s true that the Long-Term Future Fund could use funding right now. We’re working on a bunch of posts, including an explanation of our funding needs, track record over the last year, and some reflections that I hope will be out pretty soon.

I’d probably wait for us to post those if you’re a prospective LTFF donor, as they also have a bunch of relevant updates about the fund.

Is there a compiled list of what the LTFF has accomplished and how that compares to past goals and promises, if any, made to previous donors?

I know some potential donors that would be more readily convinced if they could see such a comparison and reach out to past donors.

We are hoping to release a report in the next few weeks giving a run down on our grantmaking over the last year, with some explanations for why we made the grants and some high level reflections on the fund.

Some things that might be useful:

* Fund page where we give more context on the goals of the fund: https://funds.effectivealtruism.org/funds/far-future

* Our old payout reports: https://funds.effectivealtruism.org/funds/far-future#payout-reports

* Our public grants database: https://funds.effectivealtruism.org/grants?fund=Long-Term%2520Future%2520Fund&sort=round

I'm told that a few professors in AI safety are getting approached by high net worth individuals now but don't have a good way to spend their money. Seems like there are connections to be made.

I was thinking about this the other day, it would be nice if we figured out a way to connect professors with independent researchers in some way. There’s a lot of grants that independent researchers can’t get, but professors can (https://cset.georgetown.edu/foundational-research-grants/). Plus, it would provide some mentorship to newer independent researchers. Not sure how this would be possible, though. Or if most professors who are interested are already feeling at capacity.

My guess would be they're mostly at capacity in terms of mentorship, otherwise they'd presumably just admit more PhD students. Also not sure they'd want to play grantmaker (and I could imagine that would also be really hard from a regulatory perspective---spending money from grants that go through the university can come with a lot of bureaucracy, and you can't just do whatever you want with that money).

Connecting people who want to give money with non-profits, grantmakers, or independent researchers who could use it seems much lower-hanging fruit. (Though I don't know any specifics about who these people who want to donate are and whether they'd be open to giving money to non-academics.)

From what I can tell, the field have been funding constrained since the FTX collapse.

What I think happened:

FTX had lots of money and a low bar for funding, which meant they spread a lot of money around. This meant that more project got started, and probably even more people got generally encouraged to join. Probably some project got funded that should not have been, but probably also some really good projects got started that did not get money before because not clearing the bar before due to not having the right connections, or just bad att writing grant proposals. In short FTX money and the promise of FTX money made the field grow quickly. Also there where where also some normal field growth. AIS has been growing steadily for a while.

Then FTX imploded. There where lots of chaos. Grants where promised but never paid out. Some orgs don't what to spend the money they did get from FTX because of risk of clawback risks. Other grant makers cover some of this but not all of this. It's still unclear what the new funding situation is.

Some months later, SFF, FTX and Nonlinear Network have their various grant rounds. Each of them get overwhelmed with applications. I think this is mainly from the FTX induced growth spurt, but also partly orgs still trying to recover from loss of FTX money, and just regular growth. Either way, the outcome of these grant rounds make it clear that the funding situation has changed. The bar for getting funding is higher than before.

Plug: I recently published a long post on the EA Forum on AI safety funding: An Overview of the AI Safety Funding Situation.

I also have this impression, except it seems to me that it's been like this for several months at least.

The Open Philanthropy people I asked at EAG said they think the bottleneck is that they currently don't have enough qualified AI Safety grantmakers to hand out money fast enough. And right now, the bulk of almost everyone's funding seems to ultimately come from Open Philanthropy, directly or indirectly.

This sounds more or less correct to me. Open Philanthropy (Open Phil) is the largest AI safety grant maker and spent over $70 million on AI safety grants in 2022 whereas LTFF only spent ~$5 million. In 2022, the median Open Phil AI safety grant was $239k whereas the median LTFF AI safety grant was only $19k in 2022.

Open Phil and LTFF made 53 and 135 AI safety grants respectively in 2022. This means the average Open Phil AI safety grant in 2022 was ~$1.3 million whereas the average LTFF AI safety grant was only $38k. So the average Open Phil AI safety grant is ~30 times larger than the average LTFF grant.

These calculations imply that Open Phil and LTFF make a similar number of grants (LTFF actually makes more) and that Open Phil spends much more simply because its grants tend to be much larger (~30x larger). So it seems like funds may be more constrained by their ability to evaluate and fulfill grants rather than having a lack of funding. This is not surprising given that the LTFF grantmakers apparently work part-time.

Counterintuitively, it may be easier for an organization (e.g. Redwood Research) to get a $1 million grant from Open Phil than it is for an individual to get a $10k grant from LTFF. The reason why is that both grants probably require a similar amount of administrative effort and a well-known organization is probably more likely to be trusted to use the money well than an individual so the decision is easier to make. This example illustrates how decision-making and grant-making processes are probably just as important as the total amount of money available.

LTFF specifically could be funding-constrained though given that it only spends ~$5 million per year on AI safety grants. Since ~40% of LTFF's funding comes from Open Phil and Open Phil has much more money than LTFF, one solution is for LTFF to simply ask for more money from Open Phil.

I don't know why Open Phil spends so much more on AI safety than LTFF (~14x more). Maybe it's simply because of some administrative hurdles that LTFF has when requesting money from Open Phil or maybe Open Phil would rather make grants directly.

Here is a spreadsheet comparing how much Open Phil, LTFF, and the Survival and Flourishing Fund (SFF) spend on AI safety per year.

Counter point. After the FTX collapse, OpenPhil said publicly (some EA Forum post) that they where raising their bar for funding. I.e. there are things that would have been funded before that would now not be funded. The stated reason for this is that there are generally less money around, in total. To me this sounds like the thing you would do if money is the limitation.

I don't know why OpenPhil don't spend more. Maybe they have long timelines and also don't expect any more big donors any time soon? And this is why they want to spend carefully?

I'd also add that historically I believe about two-thirds of LTFF's money has also come from OpenPhil, so LTFF doesn't represent a fully independent funder (though the decisionmaking around grants is pretty independent).

Based on what I've written here, my verdict is that AI safety seems more funding constrained for small projects and individuals than it is for organizations for the following reasons:

- The funds that fund smaller projects such as LTFF tend to have less money than other funds such as Open Phil which seems to be more focused on making larger grants to organizations (Open Phil spends 14x more per year on AI safety).

- Funding could be constrained by the throughput of grant-makers (the number of grants they can make per year). This seems to put funds like LTFF at a disadvantage since they tend to make a larger number of smaller grants so they are more constrained by throughput than the total amount of money available. Low throughput incentivizes making a small number of large grants which favors large existing organizations over smaller projects or individuals.

- Individuals or small projects tend to be less well-known than organizations so grants for them can be harder to evaluate or might be more likely to be rejected. On the other hand, smaller grants are less risky.

- The demand for funding for individuals or small projects seems like it could increase much faster than it could for organizations because new organizations take time to be created (though maybe organizations can be quickly scaled).

Some possible solutions:

- Move more money to smaller funds that tend to make smaller grants. For example, LTFF could ask for more money from Open Phil.

- Hire more grant evaluators or hire full-time grant evaluators so that there is a higher ceiling on the total number of grants that can be made per year.

- Demonstrate that smaller projects or individuals can be as effective as organizations to increase trust.

- Seek more funding: half of LTFF's funds come from direct donations so they could seek more direct donations.

- Existing organizations could hire more individuals rather than the individuals seeking funding themselves.

- Individuals (e.g. independent researchers) could form organizations to reduce the administrative load on grant-makers and increase their credibility.

Counterintuitively, it may be easier for an organization (e.g. Redwood Research) to get a $1 million grant from Open Phil than it is for an individual to get a $10k grant from LTFF. The reason why is that both grants probably require a similar amount of administrative effort and a well-known organization is probably more likely to be trusted to use the money well than an individual so the decision is easier to make. This example illustrates how decision-making and grant-making processes are probably just as important as the total amount of money available.

A priori, and talking with some grant-makers, I'd think the split would be around people & orgs who are well-known by the grant-makers, and those who are not well-known by the grant-makers. Why do you think the split is around people vs orgs?

That seems like a better split and there are outliers of course. But I think orgs are more likely to be well-known to grant-makers on average given that they tend to have a higher research output, more marketing, and the ability to organize events. An individual is like an organization with one employee.

But I think orgs are more likely to be well-known to grant-makers on average given that they tend to have a higher research output,

I think your getting the causality backwards. You need money first, before there is an org. Unless you count informal multi people collaborations as orgs.

I think people how are more well-known to grant-makers are more likely to start orgs. Where as people who are less known are more likely to get funding at all, if they aim for a smaller garant, i.e. as an independent researcher.

This matches my impression. At EAG London I was really stunned (and heartened!) at how many skilled people are pivoting into interpretability from non-alignment fields.

What about public funding? A lot of people are talking to politicians, but requesting more funding doesn't seem to be a central concern - I've heard more calls for regulation than calls for public AI x-risk funding.

Given a choice between public funding and just not having funding, I'd take a lack of funding. The incentives/selection pressures which come with public funding, especially in a field with already-terrible feedback loops, spell doom for the field.

What do you think happens in a world where there is $100 billion in yearly alignment funding? How would they be making less progress? I want to note that even horrifically inefficient systems still produce more output than "uncorrupted" hobbyists - cancer research would produce much fewer results if it were done by 300 perfectly coordinated people, even if the 300 had zero ethical/legal restraints.

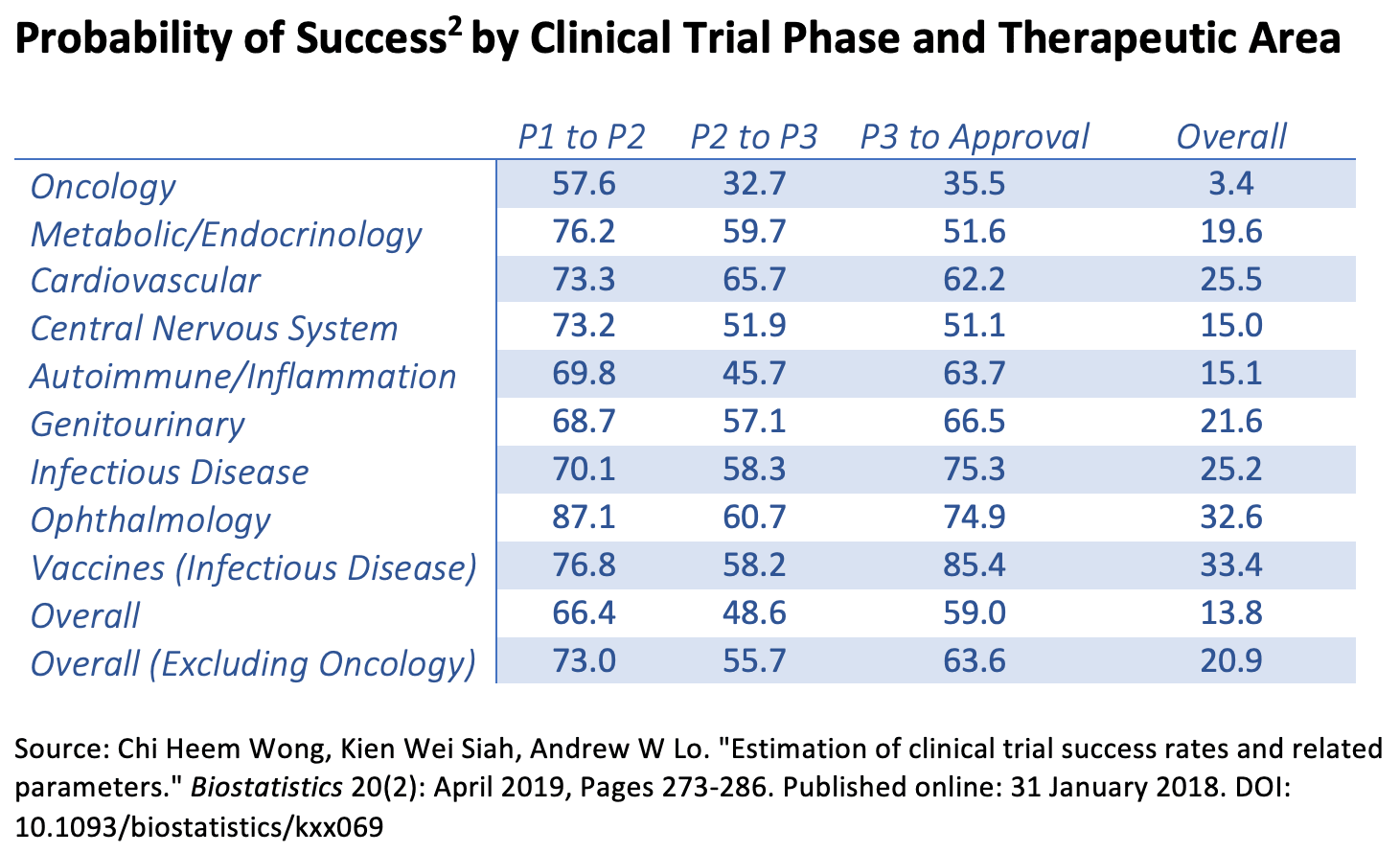

Let's take cancer as an analogy for a moment. Suppose that, as a baseline, cancer research is basically-similar to other areas of medical research. Then, some politician comes along and declares "war on cancer", and blindly pumps money into cancer research specifically. What happens? Well...

So even just from eyeballing that chart, it's pretty plausible to me that if cancer funding dropped by a factor of 10, the net effect would be that clinical trial pass rates just return to comparable levels to other areas, and the actual benefits of all that research remain roughly-the-same.

... but that's ignoring second-order effects.

Technical research fields have a "median researcher" problem: the memetic success of work in the field is not determined by the best researchers, but by the median researchers. Even if e.g. the best psychologists understand enough statistics to recognize crap studies, the median psychologist doesn't (or at least didn't 10 years ago), so we ended up with a field full of highly-memetically-successful crap studies which did not replicate (think Carol Dweck).

Back to cancer: if the large majority of the field is doing work which is predictably useless, then the field will develop standards for "success" which are totally decoupled from actual usefulness. (Note that the chart above doesn't actually imply that most of the work done in the field is useless, let alone predictably useless; there's not a one-to-one map between cancer research projects and clinical trials.) To a large extent, the new standards would be directly opposed to actual usefulness, in order to defend the entrenched researchers doing crap work - think Carol Dweck arguing that replication is a bad standard for psychology.

That's the sort of thing I expect would happen if a government dumped $100B into alignment funding. There'd be a flood of people with nominally-alignment-related projects which are in fact basically useless for solving alignment; they would quickly balloon to 90+% of the field. With such people completely dominating the field, first memetic success and then grant money would mostly be apportioned by people whose standards for success are completely decoupled from actual usefulness for alignment. Insofar as anything useful got done, it would mostly be by people who figured out the real challenges of alignment for themselves, and had to basically hack the funding system in order to get money for their actually-useful work.

In the case of cancer, steady progress has been made over the years despite the mess; at the end of the day, clinical trials provide a good ground-truth signal for progress on cancer. Even if lots of shit is thrown at the wall, some of it sticks, and that's useful. In alignment, one of the main frames for why the problem is hard is that we do not have a good ground-truth signal for whether we're making progress. So all these problems would be much worse than usual, and it's less likely to be the actually-useful shit which sticks to the metaphorical wall.

Many things here.

the issues you mention don't seem tied to public versus private funding but more about size of funding + an intrinsically difficul scientific question. I agree that at some point more funding doesn't help. At the moment, that doesn't seem to be the case in alignment. Indeed, alignment is not even as large in number of researchers as a relatively small field like linguistics.

How well the funders understand the field, and can differentially target more-useful projects, is a key variable here. For public funding, the top-level decision maker is a politician; they will in the vast majority of cases have approximately-zero understanding themselves. They will either apportion funding on purely political grounds (e.g. pork-barrel spending), or defer to whoever the consensus "experts" are in the field (which is where the median researcher problem kicks in).

In alignment to date, the funders have generally been people who understand the problem themselves to at least enough extent to notice that it's worth paying attention to (in a world where alignment concern wasn't already mainstream), and can therefore differentially target useful work, rather than blindly spray money around.

Seems overstated. Universities support all kinds of very specialized long-term research that politicians don't understand.

From my own observations and from talking with funders themselves most funding decisions in AI safety are made on mostly superficial markers - grantmakers on the whole don't dive deep on technical details. [In fact, I would argue that blindly spraying around money in a more egalitarian way (i.e. what SeriMATS has accomplished) is probably not much worse than the status-quo.]

Academia isn't perfect but on the whole it gives a lot of bright people the time, space and financial flexibility to pursue their own judgement. In fact, many alignment researchers have done a significant part of work in an academic setting or being supported in some ways by public funding.

At first, I predicted you were going to say that public funding would accelerate capabilities research over alignment but it seems like the gist of your argument is that lots of public funding would muddy the water and sharply reduce the average quality of alignment research.

That might be true for theoretical AI alignment research but I'd imagine it's less of a problem for types of AI alignment research that have decent feedback loops like interpretability research and other kinds of empirical research like experiments on RL agents.

One reason that I'm skeptical is that there doesn't seem to be a similar problem in the field of ML which is huge and largely publicly funded to the best of my knowledge and still makes good progress. Possible reasons why the ML field is still effective despite its size include sufficient empirical feedback loops and the fact that top conferences reject most papers (~25% is a typical acceptance rate for papers at NeurIPS).

Yeah, to be clear, acceleration of capabilities is a major reason why I expect public funding would be net negative, rather than just much closer to zero impact than naive multiplication would suggest.

Ignoring the capabilities issue, I think there's lots of room for uncertainty about whether a big injection of "blind funding" would be net positive, for the reasons explained above. I think we should be pretty confident that the results would be an OOM or more less positive than the naive multiplication suggests, but that's still not the same as "net negative"; the net positivity/negativity I see as much more uncertain (ignoring capabilities impact).

Accounting for capabilities impact, I think the net impact would be pretty robustly negative.

That might be true for theoretical AI alignment research but I'd imagine it's less of a problem for types of AI alignment research that have decent feedback loops like interpretability research and other kinds of empirical research like experiments on RL agents.

The parts where the bad feedback loops are, are exactly the places where the things-which-might-actually-kill-us are. Things we can see coming are exactly the things which don't particularly need research to stop, and the fact that we can see them is exactly what makes the feedback loops good. It is not an accident that the feedback loop problem is unusually severe for the field of alignment in particular.

(Which is not to say that e.g. interpretability research isn't useful - we can often get great feedback loops on things which provide a useful foundation for the hard parts later on. The point is that, if the field as a whole streetlights on things with good feedback loops, it will end up ignoring the most dangerous things.)

This seems implausible. Almost all contributions to AI alignment (from any perspective) has been through by people having implicitly or explicitly outside funding - not by hobbyist doing alignment next to their dayjob.

I am not claiming that a hobbyist-only research community would outperform today's community. I'm claiming that a hobbyist-only research community would outperform public (i.e. government) funding. Today's situation is better than either of those two: we have funding which provides incentives which, for all their flaws, are far far better than the incentives which would come with government funding.

Roll-to-disbelieve. Can you name one kind of research that wouldn't have counterfactually happened if alignment was publicly funded? Your own research seems like a good fit for academia for instance.

Can you name one kind of research that wouldn't have counterfactually happened if alignment was publicly funded?

Wrong question.

The parable of the leprechaun is relevant here:

One day, a farmer managed to catch a leprechaun. As is usual for these tales, the leprechaun offered to show the farmer where the leprechaun's gold was buried, in exchange for the leprechaun's freedom. The farmer agreed. So the leprechaun led the farmer deep into the woods, eventually stopped at a tree, and said "my gold is buried under this tree".

Unfortunately, the farmer had not thought to bring a shovel. So, the farmer tied a ribbon around the tree to mark the spot, and the leprechaun agreed not to remove it. Then the farmer returned home to fetch a shovel.

When the farmer returned, he found a ribbon tied around every tree in the forest. He never did find the gold.

This is the problem which plagues many academic fields (e.g. pre-crisis psychology is a now-clear example). It's not mainly that good research goes unfunded, it's that there's so much crap that the good work is (a) hard to find, and (b) not differentially memetically successful.

A little crap research mostly doesn't matter, so long as the competent researchers can still do their thing. But if the volume of crap reaches the point where competent researchers have trouble finding each other, or new people are mostly onboarded into crap research, or external decision-makers can't defer to a random "expert" in the field without usually getting a bunch of crap, then all that crap research has important negative effects.

It's a cute story John but do you have more than an anecdotal leprechaun?

I think the simplest model (so the one we should default to by Occam's mighty Razor) is that whether good research will be done in a field is mostly tied to

- intrinisic features of research in this area (i.e. how much feedback from reality, noisy vs nonnoisy, political implication, and lots more I don't care to name)

- initial fieldbuilding driving who self-selects into the research field

- Number of Secure funded research positions

the first is independent of funding source - I don't think we have much evidence that the second would be much worse for public funding as opposed to private funding.

in absence of strong evidence, I humbly suggest we should default to the simplest model in which :

- more money & more secure positions -> more people will be working on the problem

The fact that France has a significant larger number of effectively-tenured positions per capita than most other nations, entirely publicly funded, is almost surely one of the most important factors in its (continued) dominance in pure mathematics as evidenced by its large share of Fields medals (13/66 versus 15/66 for the US). I observe in passing that your own research program is far more akin to academic math than cancer research.

As for the position that you'd rather have no funding as opposed to public funding is ... well let us be polite and call it ... American.

(Probably not going to respond further here, but I wanted to note that this comment really hit the perfect amount of sarcasm and combativity for me personally; I enjoyed it.)

Alignment is almost exactly opposite of abstract math? Math has a good quality of being checkable - you can get a paper, follow all its content and become sure that content is valid. Alignment research paper can have valid math, but be inadequate in questions such as "is this math even related to reality?", which are much harder to check.

That may be so.

-

Wentworths own work is closest to academic math/theoretical physics, perhaps to philosophy.

-

are you claiming we have no way of telling good (alignment) research from bad? And if we do, why would private funding be better at figuring this out than public funding?

To be somewhat more fair, there are probably thousands of problems with the property that they are much easier to check than they are to solve, and while alignment research is maybe not this, I do think that there's a general gap between verifying a solution and actually solving the problem.

The canonical examples are NP problems.

Another interesting class are problems that are easy to generate but hard to verify.

John Wentworth told me the following delightfully simple example Generating a Turing machine program that halts is easy, verifying that an arbitrary TM program halts is undecidable.

Yep, I was thinking about NP problems, though #P problems for the counting version would count as well.

But if the volume of crap reaches the point where competent researchers have trouble finding each other, or new people are mostly onboarded into crap research, or external decision-makers can't defer to a random "expert" in the field without usually getting a bunch of crap, then all that crap research has important negative effects

I agree with your observation. The problem is that many people are easily influenced by others, rather than critically evaluating whether the project they're participating in is legitimate or if their work is safe to publish. It seems that most have lost the ability to listen to their own judgment and assess what is rational to do.

This would help explain some things I've been scratching my head about (revealed preferences implied by visible funding, assuming ample cash on hand, didn't seem to match well with a talent-constrained story). I'm currently trying to figure out how to prioritize earning to give versus direct research; it would be really helpful to know more about the funding situation from the perspective of the grantmaking organizations.

In particular, it'd be great to have some best-guess projections of future funding distributions, and any other information that might help fill in different values of X, Y and Z for propositions like "We would prefer X dollars in extra funding received in year Y over Z additional weekly hours of researcher time starting today."

I think part of the question is also comparative advantage. Which, if someone is seriously considering technical research, is probably a tougher-than-normal question for them in particular. (The field still has a shortage, if not always constraint, of both talent and training-capacity. And many people's timelines are short...)

In this 80,000 Hours post (written in 2021), Benjamin Todd says "I’d typically prefer someone in these roles to an additional person donating $400,000–$4 million per year (again, with huge variance depending on fit)." This seems like an argument against earning to give for most people.

On the other hand, this post emphasizes the value of small donors.

I don’t see how the quote you mentioned is an argument rather than a statement. Does the post cited provide a calculation to support that number given current funding constraints?

Edit: Reading some of the post, it definitely assumes we are in a funding overhang, which if you take John (and my own, and others’) observations at face value, then we are not.

Context of the post: funding overhang

The post was written in 2021 and argued that there was a funding overhang in longtermist causes (e.g. AI safety) because the amount of funding had grown faster than the number of people working.

The amount of committed capital increased by ~37% per year and the amount of deployed funds increased by ~21% per year since 2015 whereas the number of engaged EAs only grew ~14% per year.

The introduction of the FTX Future Fund around 2022 caused a major increase in longtermist funding which further increased the funding overhang.

Benjamin linked a Twitter update in August 2022 saying that the total committed capital was down by half because of a stock market and crypto crash. Then FTX went bankrupt a few months later.

The current situation

The FTX Future Fund no longer exists and Open Phil AI safety spending seems to have been mostly flat for the past 2 years. The post mentions that Open Phil is doing this to evaluate impact and increase capacity before possibly scaling more.

My understanding (based on this spreadsheet) is that the current level of AI safety funding has been roughly the same for the past 2 years whereas the number of AI safety organizations and researchers has been increasing by ~15% and ~30% per year respectively. So the funding overhang could be gone by now or there could even be a funding underhang.

Comparing talent vs funding

The post compares talent and funding in two ways:

- The lifetime value of a researcher (e.g. $5 million) vs total committed funding (e.g. $1 billion)

- The annual cost of a researcher (e.g. $100k) vs annual deployed funding (e.g. $100 million)

A funding overhang occurs when the total committed funding is greater than the lifetime value of all the researchers or the annual amount of funding that could be deployed per year is greater than the annual cost of all researchers.

Then the post says:

“Personally, if given the choice between finding an extra person for one of these roles who’s a good fit or someone donating $X million per year, to think the two options were similarly valuable, X would typically need to be over three, and often over 10 (where this hugely depends on fit and the circumstances).”

I forgot to mention that this statement was applied to leadership roles like research leads, entrepreneurs, and grantmakers who can deploy large amounts of funds or have a large impact and therefore can have a large amount of value. Ordinary employees probably have less financial value.

Assuming there is no funding overhang in AI safety anymore, the marginal value of funding over more researchers is higher today than it was when the post was written.

The future

If total AI safety funding does not increase much in the near term, AI safety could continue to be funding-constrained or become more funding constrained as the number of people interested in working on AI safety increases.

However, the post explains some arguments for expecting EA funding to increase:

- There’s some evidence that Open Philanthropy plans to scale up its spending over the next several years. For example, this post says, “We gave away over $400 million in 2021. We aim to double that number this year, and triple it by 2025”. Though the post was written in 2022 so it could be overoptimistic.

- According to Metaculus, there is a ~50% chance of another Good Ventures / Open Philanthropy-sized fund being created by 2026 which could substantially increase funding for AI safety.

My mildly optimistic guess is that as AI safety becomes more mainstream there will be a symmetrical effect where both more talent and funding are attracted to the field.

This comment expressed doubt that 10 million/year figure is an accurate estimation of the value of individual people at 80k/ OpenPhil in practice.

An earlier version of this comment expressed this more colorfully. Upon reflection I no longer feel comfortable discussing this in person.

You are misunderstanding. OP is saying that these people they've identified are as valuable to the org as an additional N$/y "earn-to-give"-er. They are not saying that they pay those employees N$/y.

I don't think I am misunderstanding. Unfortunately, upon reflection I don't feel comfortable discussing this in public. Sorry.

Thank you for your thougths lc.

[I don't like the $5k/life number and it generally seems sus to use a number GiveWell created (and disavows literal use of) to evaluate OpenPhil, but accepting it arguendo for this post...]

I think it's pretty easy for slightly better decision-making by someone at openphil to save many times 2000 lives/ year. I think your math is off and you mean 20,000 lives per year, which is still not that hard for me to picture. The returns on slightly better spending is easily that high, when that much money is involved.

You could argue OpenPhil grant makers are not, in practice, generating those improvements. But preferring a year of an excellent grant maker to an additional $10m doesn't seem weird for an org that, at the time, was giving away less money than it wanted to because it couldn't find enough good projects.

Sorry, I don't feel comfortable continuing this conversation in public. Thank you for your thoughts Elizabeth.

Yeah, 80k's post on the topic was written with the very explicit assumption of a funding overhang, which I do think was a correct assumption when that post was written, but has recently ceased to be a correct assumption.

committing to an earning-to-give path would be a bet on this situation being the new normal.

Is that true, or would it just be the much more reasonable bet that this situation ever occurs again? because at least in theory, a dedicated earning-to-give person could just invest money during the funding-flush times and then donate it the next time we're funding-constrained?

This lines up with our experience running our first Nonlinear Network round. We received ~500 applications, most of which did not apply to other EA funders like the LTFF. Full writeup coming soon.

If you'd like to help out, you can apply to be a funder for our next round in Oct/Nov.

It's really good to see this said out loud. I don't necessarily have a broad overview of the funding field, just my experiences of trying to get into it - both into established orgs, or trying to get funding for individual research, or for alignment-adjacent stuff - and ending up in a capabilities research company.

I wonder if this is simply the result of the generally bad SWE/CS market right now. People who would otherwise be in big tech/other AI stuff, will be more inclined to do something with alignment. Similarly, if there's less money in overall tech (maybe outside of LLM-based scams), there may be less money for alignment.

I wonder if this is simply the result of the generally bad SWE/CS market right now. People who would otherwise be in big tech/other AI stuff, will be more inclined to do something with alignment.

This is roughly my situation. Waymo froze hiring and had layoffs while continuing to increase output expectations. As a result I/we had more work. I left in March to explore AI and landed on Mechanistic Interpretability research.

I have a similar story. I left my job at Amazon this year because there were layoffs there. Also, the release of GPT-4 in March made working on AI safety seem more urgent.

Today I received a rejection email from Oliver Hybryka on behalf of Lightspeed Grants. It says Lightspeed Grants received 600 applicants, ~$150M in default funding requests, and ~$350M in maximum funding requests. Since the original amount to be distributed was $5M, only ~3% of applications could be funded.

I knew they received more applicants than they could fund but I'm surprised by how much was requested and how large the gap was.

Thank you for sharing. It's great to have a better picture of how complex this is, the non-alignment related issues that we have to solve as new researchers on top of trying to help solve the alignment problem. I think for my case, not seeking funding for the moment is the best option - as it seems to me that dwelling on the funding situation without a clear path is a waste of precious time that I can instead focus to extracting neural activity and doing model interpretability. I think its beneficial for my limited brain space/ cognitive capacity, just think of my research as a volunteer project for the next 6 months (or more).

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2024. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?

For the past few years, I've generally mostly heard from alignment grantmakers that they're bottlenecked by projects/people they want to fund, not by amount of money. Grantmakers generally had no trouble funding the projects/people they found object-level promising, with money left over. In that environment, figuring out how to turn marginal dollars into new promising researchers/projects - e.g. by finding useful recruitment channels or designing useful training programs - was a major problem.

Within the past month or two, that situation has reversed. My understanding is that alignment grantmaking is now mostly funding-bottlenecked. This is mostly based on word-of-mouth, but for instance, I heard that the recent lightspeed grants round received far more applications than they could fund which passed the bar for basic promising-ness. I've also heard that the Long-Term Future Fund (which funded my current grant) now has insufficient money for all the grants they'd like to fund.

I don't know whether this is a temporary phenomenon, or longer-term. Alignment research has gone mainstream, so we should expect both more researchers interested and more funders interested. It may be that the researchers pivot a bit faster, but funders will catch up later. Or, it may be that the funding bottleneck becomes the new normal. Regardless, it seems like grantmaking is at least funding-bottlenecked right now.

Some takeaways:

Note that I am not a grantmaker, I'm just passing on what I hear from grantmakers in casual conversation. If anyone with more knowledge wants to chime in, I'd appreciate it.