I feel like one of the most valuable things we have on LessWrong is a broad, shared epistemic framework, ideas with which we can take steps through concept-space together and reach important conclusions more efficiently than other intellectual spheres e.g. ideas about decision theory, ideas about overcoming coordination problems, etc. I believe all of the founding staff of CFAR had read the sequences and were versed in things like what it means to ask where you got your bits of evidence from, that correctly updating on the evidence has a formal meaning, and had absorbed a model of Eliezer's law-based approach to reasoning about your mind and the world.

In recent years, when I've been at CFAR events, I generally feel like at least 25% of attendees probably haven't read The Sequences, aren't part of this shared epistemic framework, and don't have an understanding of that law-based approach, and that they don't have a felt need to cache out their models of the world into explicit reasoning and communicable models that others can build on. I also have felt this way increasingly about CFAR staff over the years (e.g. it's not clear to me whether all current CFAR staff have read The Sequen

This is my favorite question of the AMA so far (I said something similar aloud when I first read it, which was before it got upvoted quite this highly, as did a couple of other staff members). The things I personally appreciate about your question are: (1) it points near a core direction that CFAR has already been intending to try moving toward this year (and probably across near-subsequent years; one year will not be sufficient); and (2) I think you asking it publicly in this way (and giving us an opportunity to make this intention memorable and clear to ourselves, and to parts of the community that may help us remember) will help at least some with our moving there.

Relatedly, I like the way you lay out the concepts.

Your essay (I mean, “question”) is rather long, and has a lot of things in it; and my desired response sure also has a lot of things in it. So I’m going to let myself reply via many separate discrete small comments because that’s easier.

(So: many discrete small comments upcoming.)

Ben Pace writes:

In recent years, when I've been at CFAR events, I generally feel like at least 25% of attendees probably haven't read The Sequences, aren't part of this shared epistemic framework, and don't have any understanding of that law-based approach, and that they don't have a felt need to cache out their models of the world into explicit reasoning and communicable models that others can build on.

The “many alumni haven't read the Sequences” part has actually been here since very near the beginning (not the initial 2012 minicamps, but the very first paid workshops of 2013 and later). (CFAR began in Jan 2012.) You can see it in our old end-of-2013 fundraiser post, where we wrote “Initial workshops worked only for those who had already read the LW Sequences. Today, workshop participants who are smart and analytical, but with no prior exposure to rationality -- such as a local politician, a police officer, a Spanish teacher, and others -- are by and large quite happy with the workshop and feel it is valuable.” We didn't name this explicitly in that post, but part of the hope was to get the workshops to work for a slightly larger/broader/more cognitively diverse set than t

that CFAR's natural antibodies weren't kicking against it hard.

Some of them were. This was a point of contention in internal culture discussions for quite a while.

(I am not currently a CFAR staff member, and cannot speak to any of the org's goals or development since roughly October 2018, but I can speak with authority about things that took place from October 2015 up until my departure at that time.)

Ben Pace writes:

“... The Gwerns and the Wei Dais and the Scott Alexanders of the world won't have learned anything from CFAR's exploration.”

I’d like to distinguish two things:

- Whether the official work activities CFAR staff are paid for will directly produce explicit knowledge in the manner valued by the Gwern etc.

- Whether that CFAR work will help educate people who later produce explicit knowledge themselves in the manner valued by Gwern etc., and who wouldn't have produced that knowledge otherwise.

#1 would be useful but isn’t our primary goal (though I think we’ve done more than none of it). #2 seems like a component of our primary goal to me (“scientists” or “producers of folks who can make knowledge in this sense” isn’t all we’re trying to produce, but it’s part of it), and is part of what I would like to see us strengthen over the coming years.

To briefly list our situation with respect to whether we are accomplishing #2 (according to me):

- There are in fact a good number of AI safety scientists in particular who seem to me to produce knowledge of this type, and who give CFAR some degree of credit for their present tendency to do this.

- On a milder level, while CFAR work

I think a crisp summary here is: CFAR is in the business of helping create scientists, more than the business of doing science. Some of the things it makes sense to do to help create scientists look vaguely science-ish, but others don't. And this sometimes causes people to worry (understandably, I think) that CFAR isn't enthused about science, or doesn't understand its value.

But if you're looking to improve a given culture, one natural move is to explore that culture's blindspots. And I think exploring those blindspots is often not going to look like an activity typical of that culture.

An example: there's a particular bug I encounter extremely often at AIRCS workshops, but rarely at other workshops. I don't yet feel like I have a great model of it, but it has something to do with not fully understanding how words have referents at different levels of abstraction. It's the sort of confusion that I think reading A Human's Guide to Words often resolves in people, and which results in people asking questions like:

- "Should I replace [my core goal x] with [this list of "ethical" goals I recently heard about]?"

- "Why is the fact that I have a goal a good reason to optimize for it?"

- "Are p

I felt a "click" in my brain reading this comment, like an old "something feels off, but I'm not sure what" feeling about rationality techniques finally resolving itself.

If this comment were a post, and I were in the curating-posts business, I'd curate it. The demystified concrete examples of the mental motion "use a tool from an unsciencey field to help debug scientists" are super helpful.

Just want to second that I think this comment is particularly important. There's a particular bug where I can get innoculated to a whole class of useful rationality interventions that don't match my smell for "rationality intervention", but the whole reason they're a blindspot in the first place is because of that smell... or something.

I feel like this comment should perhaps be an AIRCS class -- not on meta-ethics, but on 'how to think about what doing debugging your brain is, if your usual ontology is "some activities are object-level engineering, some activities are object-level science, and everything else is bullshit or recreation"'. (With meta-ethics addressed in passing as a concrete example.)

Thanks, that was really helpful. I continue to have a sense of disagreement that this is the right way to do things, so I’ll try to point to some of that. Unfortunately my comment here is not super focused, though I am just trying to say a single thing.

I recently wrote down a bunch of my thoughts about evaluating MIRI, and I realised that I think MIRI has gone through alternating phases of internal concentration and external explanation, in a way that feels quite healthy to me.

Here is what I said:

In the last 2-5 years I endorsed donating to MIRI (and still do), and my reasoning back then was always of the type "I don't understand their technical research, but I have read a substantial amount of the philosophy and worldview that was used to successfully pluck that problem out of the space of things to work on, and think it is deeply coherent and sensible and it's been surprisingly successful in figuring out AI is an x-risk, and I expect to find it is doing very sensible things in places I understand less well." Then, about a year ago, MIRI published the Embdded Agency sequence, and for the first time I thought "Oh, now I feel like I have an understanding of what the technical resear

Ben to check, before I respond—would a fair summary of your position be, "CFAR should write more in public, e.g. on LessWrong, so that A) it can have better feedback loops, and B) more people can benefit from its ideas?"

(To be clear the above is an account of why I personally feel excited about CFAR having investigated circling. I think this also reasonably describes the motivations of many staff, and of CFAR's behavior as an institution. But CFAR struggles with communicating research intuitions, too; I think in this case these intuitions did not propagate fully among our staff, and as a result that we did employ a few people for a while whose primary interest in circling seemed to me to be more like "for its own sake," and who sometimes discussed it in ways which felt epistemically unhealthy to me. I think people correctly picked up on this as worrying, and I don't want to suggest that didn't happen; just that there is, I think, a sensible reason why CFAR as an institution tends to investigate local blindspots by searching for non-locals with a patch, thereby alarming locals about our epistemic allegiance).

Philosophy strikes me as, on the whole, an unusually unproductive field full of people with highly questionable epistemics.

This is kind of tangential, but I wrote Some Thoughts on Metaphilosophy in part to explain why we shouldn't expect philosophy to be as productive as other fields. I do think it can probably be made more productive, by improving people's epistemics, their incentives for working on the most important problems, etc., but the same can be said for lots of other fields.

I certainly don’t want to turn the engineers into philosophers

Not sure if you're saying that you personally don't have an interest in doing this, or that it's a bad idea in general, but if the latter, see Counterintuitive Comparative Advantage.

I have an interest in making certain parts of philosophy more productive, and in helping some alignment engineers gain some specific philosophical skills. I just meant I'm not in general excited about making the average AIRCS participant's epistemics more like that of the average professional philosopher.

I was preparing to write a reply to the effect of “this is the most useful comment about what CFAR is doing and why that’s been posted on this thread yet” (it might still be, even)—but then I got to the part where your explanation takes a very odd sort of leap.

But we looked around, and noticed that lots of the promising people around us seemed particularly bad at extrospection—i.e., at simulating the felt senses of their conversational partners in their own minds.

It’s entirely unclear to me what this means, or why it is necessary / desirable. (Also, it seems like you’re using the term ‘extrospection’ in a quite unusual way; a quick search turns up no hits for anything like the definition you just gave. What’s up with that?)

This seemed worrying, among other reasons because early-stage research intuitions (e.g. about which lines of inquiry feel exciting to pursue) often seem to be stored sub-verbally.

There… seems to be quite a substantial line of reasoning hidden here, but I can’t guess what it is. Could you elaborate?

So we looked to specialists in extraspection for a patch.

Is there some reason to consider the folks who purvey (as you say) “woo-laden authentic relating ga

Is there some reason to consider the folks who purvey (as you say) “woo-laden authentic relating games” to be ‘specialists’ here? What are some examples of their output, that is relevant to … research intuitions? (Or anything related?)

I'm speaking for myself here, not any institutional view at CFAR.

When I'm looking at maybe-experts, woo-y or otherwise, one of the main things that I'm looking at is the nature and quality of their feedback loops.

When I think about how, in principle, one would train good intuitions about what other people are feeling at any given moment, I reason "well, I would need to be able to make predictions about that, and get immediate, reliable feedback about if my predictions are correct." This doesn't seem that far off from what Circling is. (For instance, "I have a story that you're feeling defensive" -> "I don't feel defensive, so much as righteous. And...There's a flowering of heat in my belly.")

Circling does not seem like a perfect training regime, to my naive sensors, but if I imagine a person engaging in Circling for 5000 hours, or more, it seems pretty plausible that they would get increasingly skilled along a particular axis.

This makes it se...

When I think about how, in principle, one would train good intuitions about what other people are feeling at any given moment, I reason “well, I would need to be able to make predictions about that, and get immediate, reliable feedback about if my predictions are correct.” This doesn’t seem that far off from what Circling is. (For instance, “I have a story that you’re feeling defensive” → “I don’t feel defensive, so much as righteous. And...There’s a flowering of heat in my belly.”)

Why would you expect this feedback to be reliable…? It seems to me that the opposite would be the case.

(This is aside from the fact that even if the feedback were reliable, the most you could expect to be training is your ability to determine what someone is feeling in the specific context of a Circling, or Circling-esque, exercise. I would not expect that this ability—even were it trainable in such a manner—would transfer to other situations.)

Finally, and speaking of feedback loops, note that my question had two parts—and the second part (asking for relevant examples of these purported experts’ output) is one which you did not address. Relatedly, you said:

This makes it seem worthwhile training with

I'm going to make a general point first, and then respond to some of your specific objections.

General point:

One of the things that I do, and that CFAR does, is trawl through the existing bodies of knowledge (or purported existing bodies of knowledge), that are relevant to problems that we care about.

But there's a lot of that in the world, and most of it is not very reliable. My response is only point at a heuristic that I use in assessing those bodies of knowledge, and weighing which ones to prioritize and engage with further. I agree that this heuristic on its own is insufficient for certifying a tradition or a body of knowledge as correct, or reliable, or anything.

And yes, you need to do further evaluation work before adopting a procedure. In general, I would recommend against adopting a new procedure as a habit, unless it is concretely and obviously providing value. (There are obviously some exceptions to this general rule.)

Specific points:

Why would you expect this feedback to be reliable…? It seems to me that the opposite would be the case.

On the face of it, I wouldn't assume that it is reliable, but I don't have that strong a reason to assume that i...

Some sampling of things that I'm currently investigating / interested in (mostly not for CFAR), and sources that I'm using:

- Power and propaganda

- reading the Dictator's Handbook and some of the authors' other work.

- reading Kissinger's books

- rereading Samo's draft

- some "evil literature" (an example of which is "things Brent wrote")

- thinking and writing

- Disagreement resolution and conversational mediation

- I'm currently looking into some NVC materials

- lots and lots of experimentation and iteration

- Focusing, articulation, and aversion processing

- Mostly iteration with lots of notes.

- Things like PJ EBY's excellent ebook.

- Reading other materials from the Focusing institute, etc.

- Ego and what to do about it

- Byron Katie's The Work (I'm familiar with this from years ago, it has an epistemic core (one key question is "Is this true?"), and PJ EBY mentioned using this process with clients.)

- I might check out Eckhart Tolle's work again (which I read as a teenager)

- Learning

- Mostly iteration as I learn things on the object level, right now, but I've read a lot on deliberate practice, and study methodology, as well as learned g

I think I also damaged something psychologically, which took 6 months to repair.

I've been pretty curious about the extent to which circling has harmful side effects for some people. If you felt like sharing what this was, the mechanism that caused it, and/or how it could be avoided I'd be interested.

I expect, though, that this is too sensitive/personal so please feel free to ignore.

Said I appreciate your point that I used the term "extrospection" in a non-standard way—I think you're right. The way I've heard it used, which is probably idiosyncratic local jargon, is to reference the theory of mind analog of introspection: "feeling, yourself, something of what the person you're talking with is feeling." You obviously can't do this perfectly, but I think many people find that e.g. it's easier to gain information about why someone is sad, and about how it feels for them to be currently experiencing this sadness, if you use empathy/theory of mind/the thing I think people are often gesturing at when they talk about "mirror neurons," to try to emulate their sadness in your own brain. To feel a bit of it, albeit an imperfect approximation of it, yourself.

Similarly, I think it's often easier for one to gain information about why e.g. someone feels excited about pursuing a particular line of inquiry, if one tries to emulate their excitement in one's own brain. Personally, I've found this empathy/emulation skill quite helpful for research collaboration, because it makes it easier to trade information about people's vague, sub-verbal curiosities and intuitions about e.g. "which questions are most worth asking."

Circlers don't generally use this skill for research. But it is the primary skill, I think, that circling is designed to train, and my impression is that many circlers have become relatively excellent at it as a result.

"For example, we spent a bunch of time circling for a while"

Does this imply that CFAR now spends substantially less time circling? If so and there's anything interesting to say about why, I'd be curious.

CFAR does spend substantially less time circling now than it did a couple years ago, yeah. I think this is partly because Pete (who spent time learning about circling when he was younger, and hence found it especially easy to notice the lack of circling-type skill among rationalists, much as I spent time learning about philosophy when I was younger and hence found it especially easy to notice the lack of philosophy-type skill among AIRCS participants) left, and partly I think because many staff felt like their marginal skill returns from circling practice were decreasing, so they started focusing more on other things.

Whether CFAR staff (qua CFAR staff, as above) will help educate people who later themselves produce explicit knowledge in the manner valued by Gwern, Wei Dai, or Scott Alexander, and who wouldn’t have produced (as much of) that knowledge otherwise.

This seems like a good moment to publicly note that I probably would not have started writing my multi-agent sequence without having a) participated in CFAR's mentorship training b) had conversations with/about Val and his posts.

With regard to whether our staff has read the sequences: five have, and have been deeply shaped by them; two have read about a third, and two have read little. I do think it’s important that our staff read them, and we decided to run this experiment with sabbatical months next year in part to ensure our staff had time to do this over the coming year.

I honestly think, in retrospect, that the linchpin of early CFAR's standard of good shared epistemics was probably Critch.

Note that Val's confusion seems to have been because he misunderstood Oli's point.

(apologies for this only sort-of being a question, and for perhaps being too impressed with the cleverness of my metaphor at the expense of clarity)

I have a vague model that's something like (in programming terms):

- the original LessWrong sequences were the master branch of a codebase (in terms of being a coherent framework for evaluating the world and making decisions)

- CFAR forked that codebase into (at least one) private repo and did a bunch of development on it, kinda going off in a few divergent directions. My impression that was "the CFAR dev branch" is more introspection-focused, and "internal alignment" focused.

- Many "serious rationalist" I know (including myself) have incorporated some of elements from "the CFAR dev branch" into their epistemogy (and overall worldview).

- (Although, one person said they got more from Leverage than CFAR.)

- In the past couple years, there's a bit of confusion on LessWrong (and adjaecent spaces) about what exactly the standards are, with (some) longterm members offhandedly referring to concepts that haven't been written up in longform, and with unclear epistemic tagging.

- Naively attempting to merge the latest dev branch back into "Sequences Era Le

Re: 1—“Forked codebases that have a lot in common but are somewhat tricky to merge” seems like a pretty good metaphor to me.

The question I'd like to answer that is near your questions is: "What is the minimal patch/bridge that will let us use all of both codebases without running into merge conflicts?"

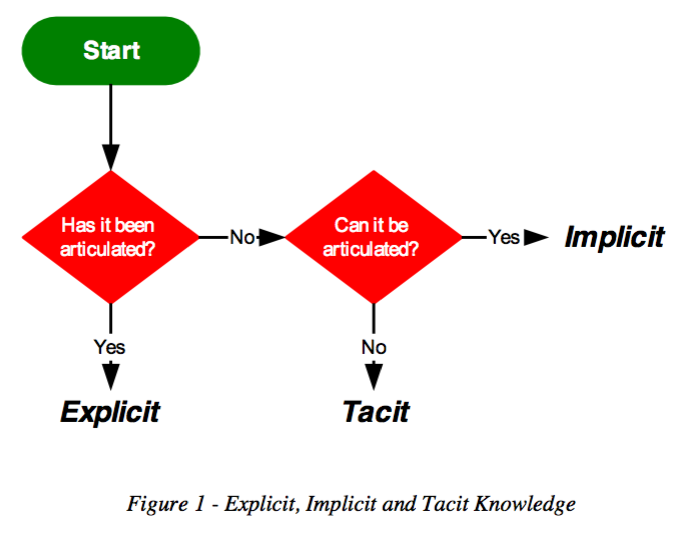

We do have a candidate answer to this question, which we’ve been trying out at AIRCS to reasonable effect. Our candidate answer is something like: an explicit distinction between “tacit knowledge” (inarticulate hunches, early-stage research intuitions, the stuff people access and see in one another while circling, etc.) and the “explicit” (“knowledge” worthy of the name, as in the LW codebase—the thing I believe Ben Pace is mainly gesturing at in his comment above).

Here’s how we explain it at AIRCS:

- By “explicit” knowledge, we mean visible-to-conscious-consideration denotative claims that are piecewise-checkable and can be passed explicitly between humans using language.

- Example: the claim “Amy knows how to ride a bicycle” is explicit.

- By “tacit” knowledge, we mean stuff that allows you to usefully navigate the world (and so contains implicit information about the world, and can b

People taking “I know it in my gut” as zero-value, and attempting to live via the explicit only. My sense is that some LessWrong users like Said_Achmiz tend to err in this direction.

This is not an accurate portrayal of my views.

I’d be happy to, except that I’m not sure quite what I need to clarify.

I mean, it’s just not true that I consider “tacit” knowledge (which may, or may not be, the same thing as procedural knowledge—but either way…) to be “zero-value”. That isn’t a thing that I believe, nor is it adjacent to some similar thing that I believe, nor is it a recognizable distortion of some different thing that I believe.

For instance, I’m a designer, and I am quite familiar with looking at a design, or design element, and declaring that it is just wrong, or that it looks right this way and not that way; or making something look a certain way because that’s what looks good and right; etc., etc. Could I explicitly explain the precise and specific reason for every detail of every design decision I make? Of course not; it’s absurd even to suggest it. There is such a thing as “good taste”, “design sense”, etc. You know quite well, I’m sure, what I am talking about.

So when someone says that I attempt to live via the explicit only, and take other sorts of knowledge as having zero value—what am I to say to that? It isn’t true, and obviously so. Perhaps Anna could say a bit about what led her to this conclusion about my views. I am happy to comment further; but as it stands, I am at a loss.

For what it's worth, I think that saying "Person X tends to err in Y direction" does not mean "Person X endorses or believes Y".

Some notes, for my own edification and that of anyone else curious about all this terminology and the concepts behind it.

Some searching turns up an article by one Fred Nickols, titled “The Knowledge in Knowledge Management” [PDF]. (As far as I can tell, “knowledge management” seems to be a field or topic of study that originates in the world of business consulting; and Fred Nickols is a former executive at a consulting firm of some sort.)

Nickols offers the following definitions:

Explicit knowledge, as the first word in the term implies, is knowledge that has been articulated and, more often than not, captured in the form of text, tables, diagrams, product specifications and so on. … An example of explicit knowledge with which we are all familiar is the formula for finding the area of a rectangle (i.e., length times width). Other examples of explicit knowledge include documented best practices, the formalized standards by which an insurance claim is adjudicated and the official expectations for performance set forth in written work objectives.

Tacit knowledge is knowledge that cannot be articulated. As Michael Polanyi (1997), the chemist-turned-philosopher who coined the term put

Also, the meetup groups are selected against for agency and initiative, because, for better or for worse, the most initiative taking people often pick up and move to the hubs in the Bay or in Oxford.

Thus spake Eliezer: "Every Cause Wants to be a Cult".

An organization promising life-changing workshops/retreats seems especially high-risk for cultishness, or at least pattern matches on it pretty well. We know the price of retaining sanity is vigilance. What specific, concrete steps are you at CFAR taking to resist the cult attractor?

What is CFAR's goal/purpose/vision/raison d'etre? Adam's post basically said "we're bad at explaining it", and an AMA sounds like a good place to at least attempt an explanation.

My closest current stab is that we’re the “Center for Bridging between Common Sense and Singularity Scenarios.” (This is obviously not our real name. But if I had to grab a handle that gestures at our raison d’etre, at the moment I’d pick this one. We’ve been internally joking about renaming ourselves this for some months now.)

To elaborate: thinking about singularity scenarios is profoundly disorienting (IMO, typically worse than losing a deeply held childhood religion or similar). Folks over and over again encounter similar failure modes as they attempt this. It can be useful to have an institution for assisting with this -- collecting concepts and tools that were useful for previous waves who’ve attempted thought/work about singularity scenarios, and attempting to pass them on to those who are currently beginning to think about such scenarios.

Relatedly, the pattern of thinking required for considering AI risk and related concepts at all is pretty different from the patterns of thinking that suffice in most other contexts, and it can be useful to have a group that attempts to collect these and pass them forward.

Further, it can be useful to figure out how the heck to do teams

Examples of some common ways that people sometimes find Singularity scenarios disorienting:

When a person loses their childhood religion, there’s often quite a bit of bucket error. A person updates on the true fact “Jehovah is not a good explanation of the fossil record” and accidentally confuses that true fact with any number of other things, such as “and so I’m not allowed to take my friends’ lives and choices as real and meaningful.”

I claimed above that “coming to take singularity scenarios seriously” seems in my experience to often cause even more disruption / bucket errors / confusions / false beliefs than does “losing a deeply held childhood religion.” I’d like to elaborate on that here by listing some examples of the kinds of confusions/errors I often encounter.

None of these are present in everyone who encounters Singularity scenarios, or even in most people who encounter it. Still, each confusion below is one where I’ve seen it or near-variants of it multiple times.

Also note that all of these things are “confusions”, IMO. People semi-frequently have them at the beginning and then get over them. These are not the POV I would recommend or consider correct -- more like the

and makes it somewhat plausible why I’m claiming that “coming to take singularity scenarios seriously can be pretty disruptive to common sense,” and such that it might be nice to try having a “bridge” that can help people lose less of the true parts of common sense as their world changes

Can you say a bit more about how CFAR helps people do this? Some of the "confusions" you mentioned are still confusing to me. Are they no longer confusing to you? If so, can you explain how that happened and what you ended up thinking on each of those topics? For example lately I'm puzzling over something related to this:

Given this, should I get lost in “what about simulations / anthropics” to the point of becoming confused about normal day-today events?

We’ve been internally joking about renaming ourselves this for some months now.

I'm not really joking about it. I wish the name better expressed what the organization does.

Though I admit that CfBCSSS, leaves a lot to be desired in terms of acronyms.

:) There's something good about "common sense" that isn't in "effective epistemics", though -- something about wanting not to lose the robustness of the ordinary vetted-by-experience functioning patterns. (Even though this is really hard, plausibly impossible, when we need to reach toward contexts far from those in which our experiences were based.)

Here’s a very partial list of blog post ideas from my drafts/brainstorms folder. Outside view, though, if I took the time to try to turn these in to blog posts, I’d end up changing my mind about more than half of the content in the process of writing it up (and then would eventually end up with blog posts with somewhat different these).

I’m including brief descriptions with the awareness that my descriptions may not parse at this level of brevity, in the hopes that they’re at least interesting teasers.

Contra-Hodgel

- (The Litany of Hodgell says “That which can be destroyed by the truth should be”. Its contrapositive therefore says: “That which can destroy [that which should not be destroyed] must not be the full truth.” It is interesting and sometimes-useful to attempt to use Contra-Hodgel as a practical heuristic: “if adopting belief X will meaningfully impair my ability to achieve good things, there must be some extra false belief or assumption somewhere in the system, since true beliefs and accurate maps should just help (e.g., if “there is no Judeo-Christian God” in practice impairs my ability to have good and compassionate friendships, perhaps there is some false belief somew

The need to coordinate in this way holds just as much for consequentialists or anyone else.

I have a strong heuristic that I should slow down and throw a major warning flag if I am doing (or recommending that someone else do) something I believe would be unethical if done by someone not aiming to contribute to a super high impact project. I (weakly) believe more people should use this heuristic.

Some off the top of my head.

- A bunch of Double Crux posts that I keep promising but am very bad at actually finishing.

- The Last Term Problem (or why saving the world is so much harder than it seems) - A abstract decision theoretic problem that has confused me about taking actions at all for the past year.

- A post on how the commonly cited paper on how "Introspection is Impossible" (Nisbett and Wilson) is misleading.

- Two takes on confabulation - About how the Elephant in the Brain thesis doesn't imply that we can't tell what our motivations actually are, just that we aren't usually motivated to.

- A lit review on mental energy and fatigue.

- A lit review on how attention works.

Most of my writing is either private strategy documents, or spur of the moment thoughts / development-nuggets that I post here.

Can you too-tersely summarize your Nisbett and Wilson argument?

Or, like... writer a teaser / movie trailer for it, if you're worried your summary would be incomplete or inoculating?

This doesn't capture everything, but one key piece is "People often confuse a lack of motivation to introspect with a lack of ability to introspect. The fact of confabulation does not demonstrate that people are unable articulate what's actually happening in principle." Very related to the other post on confabulation I note above.

Also, if I remember correctly, some of the papers in that meta analysis, just have silly setups: testing whether people can introspect into information that they couldn't have access too. (Possible that I misunderstood or am miss-remembering.)

To give a short positive account:

- All introspection depends on comparison between mental states at different points in time. You can't introspect on some causal factor that doesn't vary.

- Also, the information has to be available at the time of introspection, ie still in short term memory.

- But that gives a lot more degrees for freedom that people seem to predict, and in practice I am able to notice many subtle intentions (such as when my behavior is motivated by signalling), that others want to throw out as unknowable.

This isn’t a direct answer to, “What are the LessWrong posts that you wish you had the time to write?” It is a response to a near-by question, though, which is probably something along the lines of, “What problems are you particularly interested in right now?” which is the question that always drives my blogging. Here’s a sampling, in no particular order.

[edit: cross-posted to Ray's Open Problems post.]

There are things you’re subject to, and things you can take as object. For example, I used to do things like cry when an ambulance went by with its siren on, or say “ouch!” when I put a plate away and it went “clink”, yet I wasn’t aware that I was sensitive to sounds. If asked, “Are you sensitive to sounds?” I’d have said “No.” I did avoid certain sounds in local hill-climby ways, like making music playlists with lots of low strings but no trumpets, or not hanging out with people who speak loudly. But I didn’t “know” I was doing these things; I was *subject* to my sound sensitivity. I could not take it as *object*, so I couldn’t delib...

I have a Google Doc full of ideas. Probably I'll never write most of these, and if I do probably much of the content will change. But here are some titles, as they currently appear in my personal notes:

- Mesa-Optimization in Humans

- Primitivist Priors v. Pinker Priors

- Local Deontology, Global Consequentialism

- Fault-Tolerant Note-Scanning

- Goal Convergence as Metaethical Crucial Consideration

- Embodied Error Tracking

- Abnormally Pleasurable Insights

- Burnout Recovery

- Against Goal "Legitimacy"

- Computational Properties of Slime Mold

- Steelmanning the Verificationist Criterion of Meaning

- Manual Tribe Switching

- Manual TAP Installation

- Keep Your Hobbies

I don’t think that time is my main constraint, but here are some of my blog post shaped ideas:

- Taste propagates through a medium

- Morality: do-gooding and coordination

- What to make of ego depletion research

- Taboo "status"

- What it means to become calibrated

- The NFL Combine as a case study in optimizing for a proxy

- The ability to paraphrase

- 5 approaches to epistemics

My guesses, in no particular order:

-

Being a first employee is pretty different from being in a middle-stage organization. In particular, the opportunity to shape what will come has an appeal that can I think rightly bring in folks who you can’t always get later. (Folks present base rates for various reference classes below; I don’t know if anyone has one for “founding” vs “later” in small organizations?)

- Relatedly, my initial guess back in ~2013 (a year in) was that many CFAR staff members would “level up” while they were here and then leave, partly because of that level-up (on my model, they’d acquire agency and then ask if being here as one more staff member was or wasn’t their maximum-goal-hitting thing). I was excited about what we were teaching and hoped it could be of long-term impact to those who worked here a year or two and left, as well as to longer-term people.

-

I and we intentionally hired for diversity of outlook. We asked ourselves: “does this person bring some component of sanity, culture, or psychological understanding -- but especially sanity -- that is not otherwise represented here yet?” And this… did make early CFAR fertile, and also made it an unusual

(This is Dan, from CFAR since 2012)

Working at CFAR (especially in the early years) was a pretty intense experience, which involved a workflow that regularly threw you into these immersive workshops, and also regularly digging deeply into your thinking and how your mind works and what you could do better, and also trying to make this fledgling organization survive & function. I think the basic thing that happened is that, even for people who were initially really excited about taking this on, things looked different for them a few years later. Part of that is personal, with things like burnout, or feeling like they’d gotten their fill and had learned a large chunk of what they could from this experience, or wanting a life full of experiences which were hard to fit in to this (probably these 3 things overlap). And part of it was professional, where they got excited about other projects for doing good in the world while CFAR wanted to stay pretty narrowly focused on rationality workshops.

I’m tempted to try to go into more detail, but it feels like that would require starting to talk about particular individuals rather the set of people who were involved in early CFAR and I feel weird about that.

I am not fully sure about the correct reference class here, but employee turnover in Silicon Valley is generally very high, so that might also explain some part of the variance: https://www.inc.com/business-insider/tech-companies-employee-turnover-average-tenure-silicon-valley.html

I would guess that many startups in Silicon Valley making big promising about changing the world and then when they employers spend a year at the company, they see that there's little meaning in the work they are doing.

I've worked for 4-6 silicon valley startups now (depending on how we count it), and this has generally not been my experience. For me and most of the people I've worked with, staying in one job for a long time just seems weird. Moving around frequently is how you grow fastest and keep things interesting; people in startups see frequent job-hopping as normal, and it's the rest of the world that's strange.

That said, I have heard occasional stories about scammy startups who promise lots of equity and then suck. My impression is that they generally lure in people who haven't been in silicon valley before; people with skills, who've done this for a little while, generally won't even consider those kinds of offers.

This explanation seems unlikely to me. More likely seem to me the highly competitive labor market (with a lot of organizations trying to outbid each other), a lot of long work hours and a lot of people making enough money that leaving their job for a while is not a super big deal. It's not an implausible explanation, but I don't think it explains the variance very well.

What are your thoughts on Duncan Sabien's Facebook post which predicts significant differences in CFAR's direction now that he is no longer working for CFAR?

My rough guess is “we survived; most of the differences I could imagine someone fearing didn’t come to pass”. My correction on that rough guess is: “Okay, but insofar as Duncan was the main holder of certain values, skills, and virtues, it seems pretty plausible that there are gaps now today that he would be able to see and that we haven’t seen”.

To be a bit more specific: some of the poles I noticed Duncan doing a lot to hold down while he was here were:

- Institutional accountability and legibility;

- Clear communication with staff; somebody caring about whether promises made were kept; somebody caring whether policies were fair and predictable, and whether the institution was creating a predictable context where staff, workshop participants, and others wouldn’t suddenly experience having the rug pulled out from under them;

- Having the workshop classes start and end on time; (I’m a bit hesitant to name something this “small-seeming” here, but it is a concrete policy that supported the value above, and it is easier to track)

- Revising the handbook into a polished state;

- Having the workshop classes make sense to people, have clear diagrams and a clear point, etc.; having polish and visi

On reading Anna's above answer (which seems true to me, and also satisfies a lot of the curiosity I was experiencing, in a good way), I noted a feeling of something like "reading this, the median LWer will conclude that my contribution was primarily just ops-y and logistical, and the main thing that was at threat when I left was that the machine surrounding the intellectual work would get rusty."

It seems worth noting that my model of CFAR (subject to disagreement from actual CFAR) is viewing that stuff as a domain of study, in and of itself—how groups cooperate and function, what makes up things like legibility and integrity, what sorts of worldview clashes are behind e.g. people who think it's valuable to be on time and people who think punctuality is no big deal, etc.

But this is not necessarily something super salient in the median LWer's model of CFAR, and so I imagine the median LWer thinking that Anna's comment means my contributions weren't intellectual or philosophical or relevant to ongoing rationality development, even though I think Anna-and-CFAR did indeed view me as contributing there, too (and thus the above is also saying something like "it turned out Duncan's disappearance didn't scuttle those threads of investigation").

I agree very much with what Duncan says here. I forgot I need to point that kind of thing out explicitly. But a good bit of my soul-effort over the last year has gone into trying to inhabit the philosophical understanding of the world that can see as possibilities (and accomplish!) such things as integrity, legibility, accountability, and creating structures that work across time and across multiple people. IMO, Duncan had a lot to teach me and CFAR here; he is one of the core models I go to when I try to understand this, and my best guess is that it is in significant part his ability to understand and articulate this philosophical pole (as well as to do it himself) that enabled CFAR to move from the early-stage pile of un-transferrable "spaghetti code" that we were when he arrived, to an institution with organizational structure capable of e.g. hosting instructor trainings and taking in and making use of new staff.

(This is Dan, from CFAR since June 2012)

These are more like “thoughts sparked by Duncan’s post” rather than “thoughts on Duncan’s post”. Thinking about the question of how well you can predict what a workshop experience will be like if you’ve been at a workshop under different circumstances, and looking back over the years...

In terms of what it’s like to be at a mainline CFAR workshop, as a first approximation I’d say that it has been broadly similar since 2013. Obviously there have been a bunch of changes since January 2013 in terms of our curriculum, our level of experience, our staff, and so on, but if you’ve been to a mainline workshop since 2013 (and to some extent even before then), and you’ve also had a lifetime full of other experiences, your experience at that mainline workshop seems like a pretty good guide to what a workshop is like these days. And if you haven’t been to a workshop and are wondering what it’s like, then talking to people who have been to workshops since 2013 seems like a good way to learn about it.

More recent workshops are more similar to the current workshop than ...

What I get from Duncan’s FB post is (1) an attempt to disentangle his reputation from CFAR’s after he leaves, (2) a prediction that things will change due to his departure, and (3) an expression of frustration that more of his knowledge than necessary will be lost.

- It's a totally reasonable choice.

- At the time I first saw Duncan’s post I was more worried about big changes to our workshops from losing Duncan than I have observed since then. A year later I think the change is actually less than one would expect from reading Duncan’s post alone. That doesn’t speak to the cost of not having Duncan—since filling in for his absence means we have less attention to spend on other things, and I believe some things Duncan brought have not been replaced.

- I am also sad about this, and believe that I was the person best positioned to have caused a better outcome (smaller loss of Duncan’s knowledge and values). In other words I think Duncan’s frustration is not only understandable, but also pointing at a true thing.

At this point, you guys must have sat down with 100s of people for 1000s of hours of asking them how their mind works, prodding them with things, and seeing how they turn out like a year later. What are some things about how a person thinks that you tend to look out for as especially positive (or negative!) signs, in terms of how likely they are in the future to become more agentic? (I'd be interested in concrete things rather than attempts to give comprehensive-yet-vague answers.)

I've heard a lot of people say things along the lines that CFAR "no longer does original research into human rationality." Does that seem like an accurate characterization? If so, why is it the case that you've moved away from rationality research?

Hello, I am a CFAR contractor who considers nearly all of their job to be “original research into human rationality”. I don’t do the kind of research many people imagine when they hear the word “research” (RCT-style verifiable social science, and such). But I certainly do systematic inquiry and investigation into a subject in order to discover or revise beliefs, theories, applications, etc. Which is, you know, literally the dictionary.com definition of research.

I’m not very good at telling stories about myself, but I’ll attempt to describe what I do during my ordinary working hours anyway.

All of the time, I keep an eye out for things that seem to be missing or off in what I take to be the current art of rationality. Often I look to what I see in the people close to me, who are disproportionately members of rationality-and-EA-related organizations, watching how they solve problems and think through tricky stuff and live their lives. I also look to my colleagues at CFAR, who spend many many hours in dialogue with people who are studying rationality themselves, for the first time or on a continuing basis. But since my eyes are in my ow...

I quite like the open questions that Wei Dai wrote there, and I expect I'd find progress on those problems to be helpful for what I'm trying to do with CFAR. If I had to outline the problem we're solving from scratch, though, I might say:

- Figure out how to:

- use reason (and stay focused on the important problems, and remember “virtue of the void” and “lens that sees its own flaws, and be quick where you can) without

- going nutso, or losing humane values, and while:

- being able to coordinate well in teams.

Wei Dai’s open problems feel pretty relevant to this!

I think in practice this goal leaves me with subproblems such as:

- How do we un-bottleneck “original seeing” / hypothesis-generation;

- What is the “it all adds up to normality” skill based in; how do we teach it;

- Where does “mental energy” come from in practice, and how can people have good relationships to this;

- What’s up with people sometimes seeming self-conscious/self-absorbed (in an unfortunate, slightly untethered way) and sometimes seeming connected to “something to protect” outside themselves?

- It seems to me that “something to protect” makes people more robustly mentally healthy. Is that true? If so why? Also how d

My model is that CFAR is doing the same activity it was always doing, which one may or may not want to call “research”.

I’ll describe that activity here. I think it is via this core activity (plus accidental drift, or accidental hill-climbing in response to local feedbacks) that we have generated both our explicit curriculum, and a lot of the culture around here.

Components of this core activity (in no particular order):

- We try to teach specific skills to specific people, when we think those skills can help them. (E.g. goal-factoring; murphyjitsu; calibration training on occasion; etc.)

- We keep our eyes open while we do #1. We try to notice whether the skill does/doesn’t match the student’s needs. (E.g., is this so-called “skill” actually making them worse at something that we or they can see? Is there a feeling of non-fit suggesting something like that? What’s actually happening as the “skill” gets “learned”?)

- We call this noticing activity “seeking PCK” and spend a bunch of time developing it in our mentors and instructors.

- We try to stay in touch with some of our alumni after the workshop, and to notice what the long-term impacts seem to be (are t

That is, we were always focused on high-intensity interventions for small numbers of people -- especially the people who are the very easiest to impact (have free time; smart and reflective; lucky in their educational background and starting position). We did not expect things to generalize to larger sets.

(Mostly. We did wonder about books and things for maybe impacting the epistemics (not effectiveness) of some larger number of people a small amount. And I do personally think that if there ways to help with the general epistemic, wisdom, or sanity of larger sets of people, even if by a small amount, that would be worth meaningful tradeoffs to create. But we are not presently aiming for this (except in the broadest possible "keep our eyes open and see if we someday notice some avenue that is actually worth taking here" sense), and with the exception of helping to support Julia Galef's upcoming rationality book back when she was working here, we haven't ever attempted concrete actions aimed at figuring out how to impact larger sets of people).

I agree, though, that one should not donate to CFAR in order to increase the chances of an Elon Musk factory.

because Elon Musk is a terrible leader

This is a drive-by, but I don't believe this statement, based on the fact that Elon has successfully accomplished several hard things via the use of people organized in hierarchies (companies). I'm sure he has foibles, and it might not be fun to work for him, but he does get shit done.

What organisation, if it existed and ran independently of CFAR, would be the most useful to CFAR?

I wish someone would create good bay area community health. It isn't our core mission; it doesn't relate all that directly to our core mission; but it relates to the background environment in which CFAR and quite a few other organizations may or may not end up effective.

One daydream for a small institution that might help some with this health is as follows:

- Somebody creates the “Society for Maintaining a Very Basic Standard of Behavior”;

- It has certain very basic rules (e.g. “no physical violence”; “no doing things that are really about as over the line as physical violence according to a majority of our anonymously polled members”; etc.)

- It has an explicit membership list of folks who agree to both: (a) follow these rules; and (b) ostracize from “community events” (e.g. parties to which >4 other society members are invited) folks who are in bad standing with the society (whether or not they personally think those members are guilty).

- It has a simple, legible, explicitly declared procedure for determining who has/hasn’t entered bad standing (e.g.: a majority vote of the anonymously polled membership of the society; or an anonymous vote of a smaller “jury” randomly chosen from

No; this would somehow be near-impossible in our present context in the bay, IMO; although Berkeley's REACH center and REACH panel are helpful here and solve part of this, IMO.

No; that isn't the trouble; I could imagine us getting the money together for such a thing, since one doesn't need anything like a consensus to fund a position. The trouble is more that at this point the members of the bay area {formerly known as "rationalist"} "community" are divided into multiple political factions, or perhaps more-chaos-than-factions, which do not trust one another's judgment (even about pretty basic things, like "yes this person's actions are outside of reasonable behavioral norms). It is very hard to imagine an individual or a small committee that people would trust in the right way. Perhaps even more so after that individual or committee tried ruling against someone who really wanted to stay, and and that person attempted to create "fear, doubt, and uncertainty" or whatever about the institution that attempted to ostracize them.

I think something in this space is really important, and I'd be interested in investing significantly in any attempt that had a decent shot at helping. Though I don't yet have a strong enough read myself on what the goal ought to be.

CFAR relies heavily on selection effects for finding workshop participants. In general we do very little marketing or direct outreach, although AIRCS and MSFP do some of the latter; mostly people hear about us via word of mouth. This system actually works surprisingly (to me) well at causing promising people to apply.

But I think many of the people we would be most happy to have at a workshop probably never hear about us, or at least never apply. One could try fixing this with marketing/outreach strategies, but I worry this would disrupt the selection effects which I think have been a necessary ingredient for nearly all of our impact.

So I fantasize sometimes about a new organization being created which draws loads of people together, via selection effects similar to those which have attracted people to LessWrong, which would make it easier for us to find more promising people.

(I also—and this isn’t a wish for an organization, exactly, but it gestures at the kind of problem I speculate some organization could potentially help solve—sometimes fantasize about developing something like “scouts” at existing places with such selection effects. For example, a bunch of safety researchers competed in IMO/IOI when they were younger; I think it would be plausibly valuable for us to make friends with some team coaches, and for them to occasionally put us in touch with promising people).

What kind of people do you think never hear about CFAR but that you want to have at your workshops?

My impression is that CFAR has moved towards a kind of instruction where the goal is personal growth and increasing one's ability to think clearly about very personal/intuition-based matters, and puts significantly less emphasis on things like explicit probabilistic forecasting, that are probably less important but have objective benchmarks for success.

- Do you think that this is a fair characterisation?

- How do you think these styles of rationality should interact?

- How do you expect CFAR's relative emphasis on these styles of rationality to evolve over time?

I think it’s true that CFAR mostly moved away from teaching things like explicit probabilistic forecasting, and toward something else, although I would describe that something else differently—more like, skills relevant for hypothesis generation, noticing confusion, communicating subtle intuitions, updating on evidence about crucial considerations, and in general (for lack of a better way to describe this) “not going insane when thinking about x-risk.”

I favor this shift, on the whole, because my guess is that skills of the former type are less important bottlenecks for the problems CFAR is trying to help solve. That is, all else equal, if I could press a button to either make alignment researchers and the people who surround them much better calibrated, or much better at any of those latter skills, I’d currently press the latter button.

But I do think it’s plausible CFAR should move somewhat backward on this axis, at the margin. Some skills from the former category would be pretty easy to teach, I think, and in general I have some kelly betting-ish inclination to diversify the goals of our curricular portfolio, in case our core assumptions are wrong.

To be clear, this is not to say that those skills are bad, or even that they’re not an important part of rationality. More than half of the CFAR staff (at least 5 of the 7 current core staff, not counting myself, as a contractor) have personally trained their calibration, for instance.

In general, just because something isn’t in the CFAR workshop doesn’t mean that it isn’t an important part of rationality. The workshop is only 4 days, and not everything is well-taught in a workshop context (as opposed to [x] minutes of practice every day, for a year, or something like an undergraduate degree).

Moderator note: I've deleted six comments on this thread by users Ziz and Gwen_, who appear to be the primary people responsible for barricading off last month's CFAR alumni reunion, and who were subsequently arrested on multiple charges, including false imprisonment.

I explicitly don't want to judge the content of their allegations against CFAR, but both Ziz and Gwen_ have a sufficient track record of being aggressive offline (and Ziz also online) that I don't really want them around on LessWrong or to provide a platform to them. So I've banned them for the next 3 months (until March 19th), during which I and the other moderators will come to a more long-term decision about what to do about all of this.

On the level of individual life outcomes, do you think CFAR outperforms other self help seminars like Tony Robbins, Landmark, Alethia, etc?

I think it would depend a lot on which sort of individual life outcomes you wanted to compare. I have basically no idea where these programs stand, relative to CFAR, on things like increasing participant happiness, productivity, relationship quality, or financial success, since CFAR mostly isn't optimizing for producing effects in these domains.

I would be surprised if CFAR didn't come out ahead in terms of things like increasing participants' ability to notice confusion, communicate subtle intuitions, and navigate pre-paradigmatic technical research fields. But I'm not sure, since in general I model these orgs as having sufficiently different goals than us that I haven't spent much time learning about them.

I'm not sure, since in general I model these orgs as having sufficiently different goals than us that I haven't spent much time learning about them.

Note that as someone who has participated in many other workshops, and who is very well read in other self-help schools, I think this is a clear blind spot and missstep of CFAR.

I think you would have discovered many other powerful concepts for running effective workshops, and been significantly further with rationality techniques, if you took these other organizations seriously as both competition and sources of knowledge, and had someone on staff who spent a significant amount of time simply stealing from existing schools of thought.

I haven't done any of the programs you mentioned. And I'm pretty young, so my selection is limited. But I've done lots of personal development workshop and trainings, both before and after my CFAR workshop, and my CFAR workshop was far and above the densest in terms of content, and most transformative on both my day-to-day processing, and my life trajectory.

The only thing that compares are some dedicated, years long relationships with skilled mentors.

YMMV. I think my experience was an outlier.

How much interesting stuff do you think there is in your curriculum that hasn't percolated into the community? What's stopping said percolation?

Is there something you find yourselves explaining over and over again in person, and that you wish you could just write up in an AMA once and for all where lots of people will read it, and where you can point people to in future?

Does CFAR "eat its own dogfood"? Do the cognitive tools help in running the organization itself? Can you give concrete examples? Are you actually outperforming comparable organizations on any obvious metric due to your "applied rationality"? (Why ain'tcha rich? Or are you?)

A response to just the first three questions. I’ve been at CFAR for two years (since January 2018). I've noticed, especially during the past 2-3 months, that my mind is changing. Compared to a year, or even 6 months ago, it seems to me that my mind more quickly and effortlessly moves in some ways that are both very helpful and resemble some of the cognitive tools we offer. There’s obviously a lot of stuff CFAR is trying to do, and a lot of techniques/concepts/things we offer and teach, so any individual’s experience needs to be viewed as part of a larger whole. With that context in place, here are a few examples from my life and work:

- Notice the person I'm talking to is describing a phenomenon but I can't picture anything —> Ask for an example (Not a technique we formally teach at the workshop, but seems to me like a basic application of being specific. In that same vein: while teaching or explaining a concept, I frequently follow a concrete-abstract-concrete structure.)

- I'm making a plan —> Walk through it, inner sim / murphyjitsu style (I had a particularly vivid and exciting instance of this a few weeks ago: I was packi

(Just responding here to whether or not we dogfood.)

I always have a hard time answering this question, and nearby questions, personally.

Sometimes I ask myself whether I ever use goal factoring, or seeking PCK, or IDC, and my immediate answer is “no”. That’s my immediate answer because when I scan through my memories, almost nothing is labeled “IDC”. It’s just a continuous fluid mass of ongoing problem solving full of fuzzy inarticulate half-formed methods that I’m seldom fully aware of even in the moment.

A few months ago I spent some time paying attention to what’s going on here, and what I found is that I’m using either the mainline workshop techniques, or something clearly descended from them, many times a day. I almost never use them on purpose, in the sense of saying “now I shall execute the goal factoring algorithm” and then doing so. But if I snap my fingers every time I notice a feeling of resolution and clarification about possible action, I find that I snap my fingers quite often. And if, after snapping my fingers, I run through my recent memories, I tend to find that I’ve just done goal f...

So, is CFAR rich?

I don’t really know, because I’m not quite sure what CFAR’s values are as an organization, or what its extrapolated volition would count as satisfaction criteria.

My guess is “not much, not yet”. According to what I think it wants to do, it seems to me like its progress on that is small and slow. It seems pretty disorganized and flaily much of the time, not great at getting the people it most needs, and not great at inspiring or sustaining the best in the people it has.

I think it’s *impressively successful* given how hard I think the problem really is, but in absolute terms, I doubt it’s succeeding enough.

If it weren’t dogfooding, though, it seems to me that CFAR would be totally non-functional.

Why would it be totally non-functional? Well, that’s really hard for me to get at. It has something to do with what sort of thing a CFAR even is, and what it’s trying to do. I *do* think I’m right about this, but most of the information hasn’t made it into the crisp kinds of thoughts I can see clearly and make coherent words about. I figured I’d just go ahead and post this anyhow, and y'all can make or not-make what you want of my intuitions.

More about why CFAR would be non-functional if it weren’t dogfooding:

As I said, my thoughts aren’t really in such a state that I know how to communicate them coherently. But I’ve often found that going ahead and communicating incoherently can nevertheless be valuable; it lets people’s implicit models interact more rapidly (both between people and within individuals), which can lead to developing explicit models that would otherwise have remained silent.

So, when I find myself in this position, I often throw a creative prompt to the part of my brain that thinks it knows something, and don’t bother trying to be coherent, just to start to draw out the shape of a thing. For example, if CFAR were a boat, what sort of boat would it be?

If CFAR were a boat, it would be a collection of driftwood bound together with twine. Each piece of driftwood was yanked from the shore in passing when the boat managed to get close enough for someone to pull it in. The riders of the boat are constantly re-organizing the driftwood (while standing on it), discarding parts (both deliberately and accidentally), and trying out variations on rudders and oars and sails. All the w...

I think we eat our own dogfood a lot. It’s pretty obvious in meetings—e.g., people do Focusing-like moves to explain subtle intuitions, remind each other to set TAPs, do explicit double cruxing, etc.

As to whether this dogfood allows us to perform better—I strongly suspect so, but I’m not sure what legible evidence I can give about that. It seems to me that CFAR has managed to have a surprisingly large (and surprisingly good) effect on AI safety as a field, given our historical budget and staff size. And I think there are many attractors in org space (some fairly powerful) that would have made CFAR less impactful, had it fallen into them, that it’s avoided falling into in part because its staff developed unusual skill at noticing confusion and resolving internal conflict.

I'm reading the replies of current CFAR staff with great interest (I'm a former staff member who ended work in October 2018), as my own experience within the org was "not really; to some extent yes, in a fluid and informal way, but I rarely see us sitting down with pen and paper to do explicit goal factoring or formal double crux, and there's reasonable disagreement about whether that's good, bad, or neutral."

What are the most important considerations for CFAR with regards to whether or not to publish the Handbook?

Historically, CFAR had the following concerns (I haven't worked there since Oct 2018, so their thinking may have changed since then; if a current staff member gets around to answering this question you should consider their answer to trump this one):

- The handbook material doesn't actually "work" in the sense that it can change lives; the workshop experience is crucial to what limited success CFAR *is* able to have, and there's concern about falsely offering hope

- There is such a thing as idea inoculation; the handbook isn't perfect and certainly can't adjust itself to every individual person's experience and cognitive style. If someone gets a weaker, broken, or uncanny-valley version of a rationality technique out of a book, not only may it fail to help them in any way, but it will also make subsequently learning [a real and useful skill that's nearby in concept space] correspondingly more difficult, both via conscious dismissiveness and unconscious rounding-off.

- To the extent that certain ideas or techniques only work in concert or as a gestalt, putting the document out on the broader internet where it will be chopped up and rearranged and quoted in chunks and riffed off of and likely misinterpreted, etc., might be worse than not putting it out at all.

Back in April, Oliver Habryka wrote:

Anna Salamon has reduced her involvement in the last few years and seems significantly less involved with the broader strategic direction of CFAR (though she is still involved in some of the day-to-day operations, curriculum development, and more recent CFAR programmer workshops). [Note: After talking to Anna about this, I am now less certain of whether this actually applies and am currently confused on this point]

Could someone clarify the situation? (Possible sub-questions: Why did Oliver get this impression? Why was he confused even after talking talking to Anna? To what extent and in what ways has Anna reduced her involvement in CFAR in the last few years? If Anna has reduced her involvement in CFAR, what is she spending her time on instead?)

I’ve worked closely with CFAR since it’s founding in 2012, for varying degrees of closely (ranging from ~25 hrs/week to ~60 hrs/week). My degree of involvement in CFAR’s high-level and mid-level strategic decisions has varied some, but at the moment is quite high, and is likely to continue to be quite high for at least the coming 12 months.

During work-type hours in which I’m not working for CFAR, my attention is mostly on MIRI on MIRI’s technical research. I do a good bit of work with MIRI (though I am not employed by MIRI -- I just do a lot of work with them), much of which also qualifies as CFAR work (e.g., running the AIRCS workshops and assisting with the MIRI hiring process; or hanging out with MIRI researchers who feel “stuck” about some research/writing/etc. type thing and want a CFAR-esque person to help them un-stick). I also do a fair amount of work with MIRI that does not much overlap CFAR (e.g. I am a MIRI board member).

Oliver remained confused after talking with me in April because in April I was less certain how involved I was going to be in upcoming strategic decisions. However, it turns out the answer was “lots.” I have a lot of hopes and vision for CFAR over t

What important thing do you believe about rationality, that most others in the rationality community do not?

I'd be interested in both

- An organizational thesis level, IE, a belief that guides the strategic direction of the organization

- an individual level from people who are responding to the AMA.

I feel like CFAR has learned a lot about how to design a space to bring about certain kinds of experiences in the people in that space (i.e. encouraging participants to re-examine their lives and how their minds work). What are some surprising things you've learned about this, that inform how you design e.g. CFAR's permanent venue?

Ambience and physical comfort are surprisingly important. In particular:

-

Lighting: Have lots of it! Ideally incandescent but at least ≥ 95 CRI (and mostly ≤ 3500k) LED, ideally coming from somewhere other than the center of the ceiling, ideally being filtered through a yellow-ish lampshade that has some variation in its color so the light that gets emitted has some variation too (sort of like the sun does when filtered through the atmosphere).

-

Food/drink: Have lots of it! Both in terms of quantity and variety. The cost to workshop quality of people not having their preferences met here sufficiently outweighs the cost of buying too much food, that in general it’s worth buying too much as a policy. It's particularly important to meet people's (often, for rationalists, amusingly specific) specific dietary needs, have a variety of caffeine options, and provide a changing supply of healthy, easily accessible snacks.

-

Furniture: As comfortable as possible, and arranged such that multiple small conversations are more likely to happen than one big one.

We have not conducted thorough scientific investigation of our lamps, food or furniture. Just as one might have reasonable confidence in a proposition like "tired people are sometimes grumpy" without running an RCT, one can I think be reasonably confident that e.g. vegetarians will be upset if there’s no vegetarian food, or that people will be more likely to clump in small groups if the chairs are arranged in small groups.

I agree the lighting recommendations are quite specific. I have done lots of testing (relative to e.g. the average American) of different types of lamps, with different types of bulbs in different rooms, and have informally gathered data about people’s preferences. I have not done this formally, since I don’t think that would be worth the time, but in my informal experience, the bulb preferences of the subset of people who report any strong lighting preferences at all tend to correlate strongly with that bulb’s CRI. Currently incandescents have the highest CRI of commonly-available bulbs, so I generally recommend those. My other suggestions were developed via a similar process.

Yes, when the better way takes more resources.

On the meta level, I claim that doing things the usual way most of the time is the optimal / rational / correct way to do things. Resources are not infinite, trade-offs exist, etc.

EDIT: for related thoughts, see Vaniver's recent post on T-Shaped Organizations.

Strongly second this. Running a formal experiment is often much more costly from a decision theoretic perspective than other ways of reducing uncertainty.

On the other hand, suggestions such as “at least ≥ 95 CRI (and mostly ≤ 3500k) LED, ideally coming from somewhere other than the center of the ceiling, ideally being filtered through a yellow-ish lampshade” make no sense at all if arrived at via… what, exactly? Just trying different things and seeing which of them seemed like it was good?

Why not?

If you're running many, many events, and one of your main goals is to get good conversations happening you'll begin to build up an intuition about which things help and hurt. For instance, look at a room, and be like "it's too dark in here." Then you go get your extra bright lamps, and put them in the middle of the room, and everyone is like "ah, that is much better, I hadn't even noticed."

It seems like if you do this enough, you'll end up with pretty specific recommendations like what Adam outlined.

Actually, I think this touches on something that is useful to understand about CFAR in general.

Most of our "knowledge" (about rationality, about running workshops, about how people can react to x-risk, etc.) is what I might call "trade knowledge", it comes from having lots of personal experience in the domain, and building up good procedures via mostly-trial and error (plus metacognition and theorizing about noticed problems might be, and how to fix them).

This is distinct from scientific knowledge, which is build up from robustly verified premises, tested by explicit attempts at falsification.

(I'm reminded of an old LW post, that I can't find, about Eliezer giving some young kid (who wants to be a writer) writing advice, while a bunch of bystanders signal that they don't regard Eliezer as trustworthy.)

For instance, I might lead someone through an IDC like process at a CFAR workshop. This isn't because I've done rigorous tests (or I know of others who have done rigorous tests) of IDC, or because I've concluded from the neuroscience literature the IDC is the optimal process for arriving at true beliefs.

Rather, its that I (and other ...

The two best books on Rationality:

- The Sequences

- Principles by Ray Dalio (I read the PDF that leaked from bridge water. I haven't even looked at the actual book.)

My starter kit for people who want to build the core skills of the mind / personal effectiveness stuff (I reread all of these, for reminders, every 2 years or so):

- Getting things Done: the Art of Stress-free Productivity

- Nonviolent Communication: a Language for Life

- Focusing

- Thinking, Fast and Slow

Metaphors We Live By by George Lakoff — Totally changed the way I think about language and metaphor and frames when I read it in college. Helped me understand that there are important kinds of knowledge that aren't explicit.

I really like Language, Truth and Logic, by A.J. Ayer. It's an old book (1936) and it's silly in some ways. It's basically an early pro-empiricism manifesto, and I think many of its arguments are oversimplified, overconfident, or wrong. Even so, it does a great job of teaching some core mental motions of analytic philosophy. And its motivating intuitions feel familiar—I suspect that if 25-year-old Ayer got transported to the present, given internet access etc., we would see him on LessWrong pretty quick.

What mistakes have you made at CFAR that you have learned the most from? (Individually or as an organization?)

I have seen/heard from at least two sources something to the effect that MIRI/CFAR leadership (and Anna in particular) has very short AI timelines and high probability of doom (and apparently having high confidence in these beliefs). Here is the only public example that I can recall seeing. (Of the two examples I can specifically recall, this is not the better one, but the other was not posted publicly.) Is there any truth to these claims?

Riceissa's question was brief, so I'll add a bunch of my thoughts on this topic.