This post is a not a so secret analogy for the AI Alignment problem. Via a fictional dialog, Eliezer explores and counters common questions to the Rocket Alignment Problem as approached by the Mathematics of Intentional Rocketry Institute.

MIRI researchers will tell you they're worried that "right now, nobody can tell you how to point your rocket’s nose such that it goes to the moon, nor indeed any prespecified celestial destination."

Popular Comments

Recent Discussion

tl;dr: LessWrong released an album! Listen to it now on Spotify, YouTube, YouTube Music, or Apple Music.

On April 1st 2024, the LessWrong team released an album using the then-most-recent AI music generation. All the music is fully AI-generated, and the lyrics are adapted (mostly by humans) from LessWrong posts (or other writing LessWrongers might be familiar with).

We made probably 3,000-4,000 song generations to get the 15 we felt happy about, which I think works out to about 5-10 hours of work per song we used (including all the dead ends and things that never worked out).

The album is called I Have Been A Good Bing. I think it is a pretty fun album and maybe you'd enjoy it if you listened to it! Some of my favourites are...

I agree! I’ve been writing then generating my own LW inspired songs now.

I wish it was common for LW posts to have accompanying songs now.

Authors: Senthooran Rajamanoharan*, Arthur Conmy*, Lewis Smith, Tom Lieberum, Vikrant Varma, János Kramár, Rohin Shah, Neel Nanda

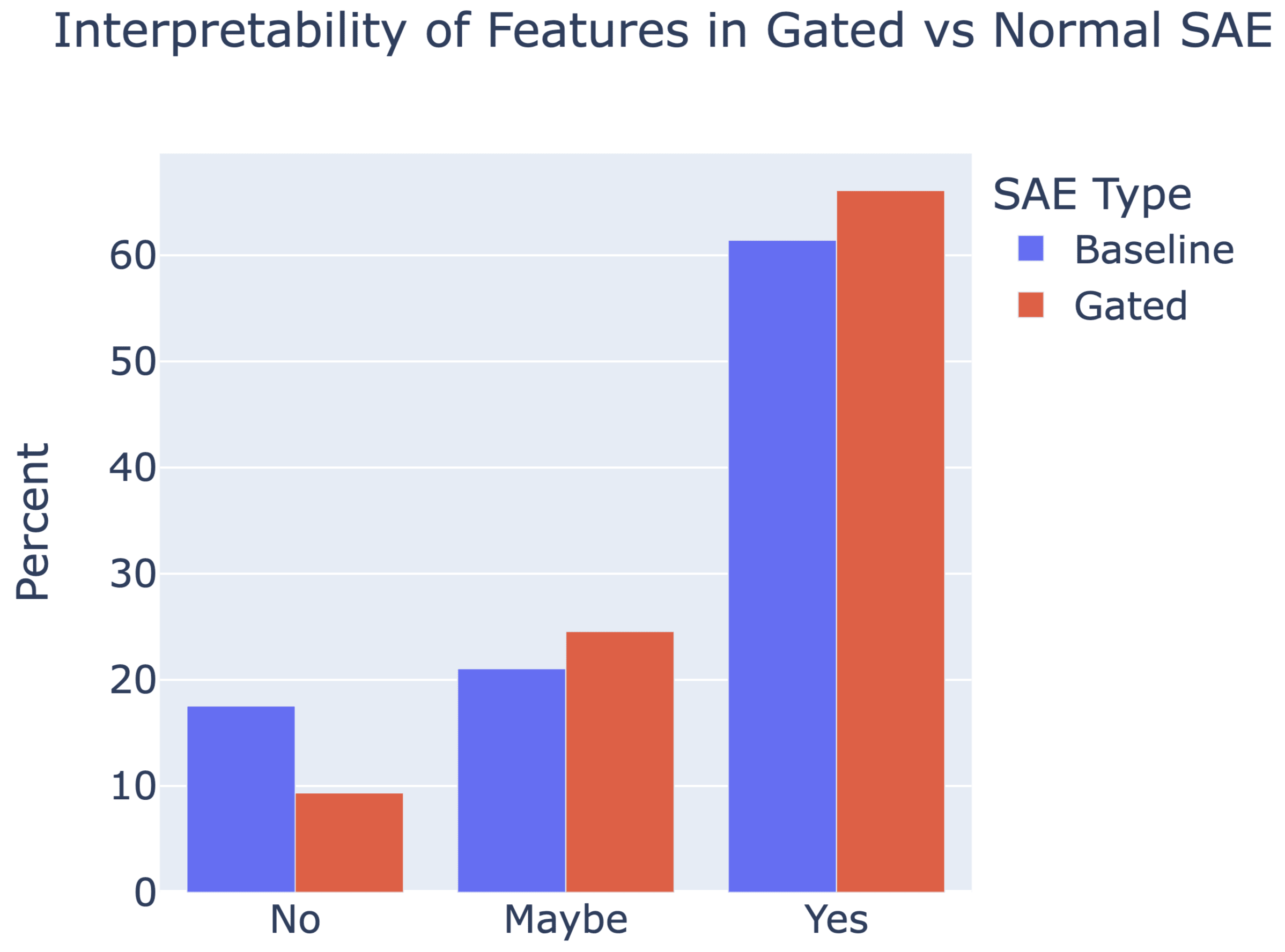

A new paper from the Google DeepMind mech interp team: Improving Dictionary Learning with Gated Sparse Autoencoders!

Gated SAEs are a new Sparse Autoencoder architecture that seems to be a significant Pareto-improvement over normal SAEs, verified on models up to Gemma 7B. They are now our team's preferred way to train sparse autoencoders, and we'd love to see them adopted by the community! (Or to be convinced that it would be a bad idea for them to be adopted by the community!)

They achieve similar reconstruction with about half as many firing features, and while being either comparably or more interpretable (confidence interval for the increase is 0%-13%).

See Sen's Twitter summary, my Twitter summary, and the paper!

Re dictionary width, 2**17 (~131K) for most Gated SAEs, 3*(2**16) for baseline SAEs, except for the (Pythia-2.8B, Residual Stream) sites we used 2**15 for Gated and 3*(2**14) for baseline since early runs of these had lots of feature death. (This'll be added to the paper soon, sorry!). I'll leave the other Qs for my co-authors

Just before the Trinity test, Enrico Fermi decided he wanted a rough estimate of the blast's power before the diagnostic data came in. So he dropped some pieces of paper from his hand as the blast wave passed him, and used this to estimate that the blast was equivalent to 10 kilotons of TNT. His guess was remarkably accurate for having so little data: the true answer turned out to be 20 kilotons of TNT.

Fermi had a knack for making roughly-accurate estimates with very little data, and therefore such an estimate is known today as a Fermi estimate.

Why bother with Fermi estimates, if your estimates are likely to be off by a factor of 2 or even 10? Often, getting an estimate within a factor of 10...

To help remember this post and it's methods I broke it down into song lyrics and used Udio to make the song.

Crosspost from my blog.

If you spend a lot of time in the blogosphere, you’ll find a great deal of people expressing contrarian views. If you hang out in the circles that I do, you’ll probably have heard of Yudkowsky say that dieting doesn’t really work, Guzey say that sleep is overrated, Hanson argue that medicine doesn’t improve health, various people argue for the lab leak, others argue for hereditarianism, Caplan argue that mental illness is mostly just aberrant preferences and education doesn’t work, and various other people expressing contrarian views. Often, very smart people—like Robin Hanson—will write long posts defending these views, other people will have criticisms, and it will all be such a tangled mess that you don’t really know what to think about them.

For...

Similarly, the lab leak theory—one of the more widely accepted and plausible contrarian views—also doesn’t survive careful scrutiny. It’s easy to think it’s probably right when your perception is that the disagreement is between people like Saar Wilf and government bureaucrats like Fauci. But when you realize that some of the anti-lab leak people are obsessive autists who have studied the topic a truly mind-boggling amount, and don’t have any social or financial stake in the outcome, it’s hard to be confident that they’re wrong.

This is a very poor concl...

U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo announced today additional members of the executive leadership team of the U.S. AI Safety Institute (AISI), which is housed at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Raimondo named Paul Christiano as Head of AI Safety, Adam Russell as Chief Vision Officer, Mara Campbell as Acting Chief Operating Officer and Chief of Staff, Rob Reich as Senior Advisor, and Mark Latonero as Head of International Engagement. They will join AISI Director Elizabeth Kelly and Chief Technology Officer Elham Tabassi, who were announced in February. The AISI was established within NIST at the direction of President Biden, including to support the responsibilities assigned to the Department of Commerce under the President’s landmark Executive Order.

...Paul Christiano, Head of AI Safety, will design

This thread seems unproductive to me, so I'm going to bow out after this. But in case you're actually curious: at least in the case of Open Philanthropy, it's easy to check what their primary concerns are because they write them up. And accidental release from dual use research is one of them.

The history of science has tons of examples of the same thing being discovered multiple time independently; wikipedia has a whole list of examples here. If your goal in studying the history of science is to extract the predictable/overdetermined component of humanity's trajectory, then it makes sense to focus on such examples.

But if your goal is to achieve high counterfactual impact in your own research, then you should probably draw inspiration from the opposite: "singular" discoveries, i.e. discoveries which nobody else was anywhere close to figuring out. After all, if someone else would have figured it out shortly after anyways, then the discovery probably wasn't very counterfactually impactful.

Alas, nobody seems to have made a list of highly counterfactual scientific discoveries, to complement wikipedia's list of multiple discoveries.

To...

Though the Greeks actually credited the idea to an even earlier Phonecian, Mochus of Sidon.

Through when it comes to antiquity credit isn't really "first to publish" as much as "first of the last to pass the survivorship filter."

It seems to me worth trying to slow down AI development to steer successfully around the shoals of extinction and out to utopia.

But I was thinking lately: even if I didn’t think there was any chance of extinction risk, it might still be worth prioritizing a lot of care over moving at maximal speed. Because there are many different possible AI futures, and I think there’s a good chance that the initial direction affects the long term path, and different long term paths go to different places. The systems we build now will shape the next systems, and so forth. If the first human-level-ish AI is brain emulations, I expect a quite different sequence of events to if it is GPT-ish.

People genuinely pushing for AI speed over care (rather than just feeling impotent) apparently think there is negligible risk of bad outcomes, but also they are asking to take the first future to which there is a path. Yet possible futures are a large space, and arguably we are in a rare plateau where we could climb very different hills, and get to much better futures.

- What plateau? Why pause now (vs say 10 years ago)? Why not wait until after the singularity and impose a "long reflection" when we will be in an exponentially better place to consider such questions.

- Singularity 5-10 years from now vs 15-20 years from now determines whether or not some people I personally know and care about will be alive.

- Every second we delay the singularity leads to a "cosmic waste" as millions more galaxies move permanently behind the event horizon defined by the expanding universe

- Slower is not prima facia safer. To the

About a year ago I decided to try using one of those apps where you tie your goals to some kind of financial penalty. The specific one I tried is Forfeit, which I liked the look of because it’s relatively simple, you set single tasks which you have to verify you have completed with a photo.

I’m generally pretty sceptical of productivity systems, tools for thought, mindset shifts, life hacks and so on. But this one I have found to be really shockingly effective, it has been about the biggest positive change to my life that I can remember. I feel like the category of things which benefit from careful planning and execution over time has completely opened up to me, whereas previously things like this would be largely down to the...

it very much depends on where the user came from

Can you provide any further detail here, i.e. be more specific on origin-stratified-retention rates? (I would appreciate this, even if this might require some additional effort searching)