The Best of LessWrong

For the years 2018, 2019 and 2020 we also published physical books with the results of our annual vote, which you can buy and learn more about here.

Rationality

Optimization

/h4ajljqfx5ytt6bca7tv)

/h4ajljqfx5ytt6bca7tv)

/h4ajljqfx5ytt6bca7tv)

/h4ajljqfx5ytt6bca7tv)

World

Practical

AI Strategy

Technical AI Safety

%20and%20a%20black%20box%20which%20no%20one%20understands%20but%20works%20perfectly%20(representing%20search)/yf2xrrlv4rqga5h8lolh)

%20and%20a%20black%20box%20which%20no%20one%20understands%20but%20works%20perfectly%20(representing%20search)/yf2xrrlv4rqga5h8lolh)

%20and%20a%20black%20box%20which%20no%20one%20understands%20but%20works%20perfectly%20(representing%20search)/yf2xrrlv4rqga5h8lolh)

%20and%20a%20black%20box%20which%20no%20one%20understands%20but%20works%20perfectly%20(representing%20search)/yf2xrrlv4rqga5h8lolh)

/h4ajljqfx5ytt6bca7tv)

/h4ajljqfx5ytt6bca7tv)

/h4ajljqfx5ytt6bca7tv)

/h4ajljqfx5ytt6bca7tv)

%20and%20a%20black%20box%20which%20no%20one%20understands%20but%20works%20perfectly%20(representing%20search)/yf2xrrlv4rqga5h8lolh)

%20and%20a%20black%20box%20which%20no%20one%20understands%20but%20works%20perfectly%20(representing%20search)/yf2xrrlv4rqga5h8lolh)

%20and%20a%20black%20box%20which%20no%20one%20understands%20but%20works%20perfectly%20(representing%20search)/yf2xrrlv4rqga5h8lolh)

%20and%20a%20black%20box%20which%20no%20one%20understands%20but%20works%20perfectly%20(representing%20search)/yf2xrrlv4rqga5h8lolh)

How does it work to optimize for realistic goals in physical environments of which you yourself are a part? E.g. humans and robots in the real world, and not humans and AIs playing video games in virtual worlds where the player not part of the environment. The authors claim we don't actually have a good theoretical understanding of this and explore four specific ways that we don't understand this process.

Paul Christiano paints a vivid and disturbing picture of how AI could go wrong, not with sudden violent takeover, but through a gradual loss of human control as AI systems optimize for the wrong things and develop influence-seeking behaviors.

The original draft of Ayeja's report on biological anchors for AI timelines. The report includes quantitative models and forecasts, though the specific numbers were still in flux at the time. Ajeya cautions against wide sharing of specific conclusions, as they don't yet reflect Open Philanthropy's official stance.

Strong evidence is much more common than you might think. Someone telling you their name provides about 24 bits of evidence. Seeing something on Wikipedia provides enormous evidence. We should be willing to update strongly on everyday events.

A few dozen reason that Eliezer thinks AGI alignment is an extremely difficult problem, which humanity is not on track to solve.

As LLMs become more powerful, it'll be increasingly important to prevent them from causing harmful outcomes. Researchers have investigated a variety of safety techniques for this purpose. However, researchers have not evaluated whether such techniques still ensure safety if the model is itself intentionally trying to subvert them. In this paper developers and evaluates pipelines of safety protocols that are robust to intentional subversion.

This post is a not a so secret analogy for the AI Alignment problem. Via a fictional dialog, Eliezer explores and counters common questions to the Rocket Alignment Problem as approached by the Mathematics of Intentional Rocketry Institute.

MIRI researchers will tell you they're worried that "right now, nobody can tell you how to point your rocket’s nose such that it goes to the moon, nor indeed any prespecified celestial destination."

AI researchers warn that advanced machine learning systems may develop their own internal goals that don't match what we intended. This "mesa-optimization" could lead AI systems to pursue unintended and potentially dangerous objectives, even if we tried to design them to be safe and aligned with human values.

A collection of 11 different proposals for building safe advanced AI under the current machine learning paradigm. There's a lot of literature out there laying out various different approaches, but a lot of that literature focuses primarily on outer alignment at the expense of inner alignment and doesn't provide direct comparisons between approaches.

Anna Salamon argues that "PR" is a corrupt concept that can lead to harmful and confused actions, while safeguarding one's "reputation" or "honor" is generally fine. PR involves modeling what might upset people and avoiding it, while reputation is about adhering to fixed standards.

"Wait, dignity points?" you ask. "What are those? In what units are they measured, exactly?"

And to this I reply: "Obviously, the measuring units of dignity are over humanity's log odds of survival - the graph on which the logistic success curve is a straight line. A project that doubles humanity's chance of survival from 0% to 0% is helping humanity die with one additional information-theoretic bit of dignity."

"But if enough people can contribute enough bits of dignity like that, wouldn't that mean we didn't die at all?" "Yes, but again, don't get your hopes up."

If you're looking for ways to help with the whole “the world looks pretty doomed” business, here's my advice: look around for places where we're all being total idiots. Look around for places where something seems incompetently run, or hopelessly inept, and where some part of you thinks you can do better.

Then do it better.

Eliezer describes the similarity between understanding what a locally valid proof step is in mathematics, knowing there are bad arguments for true conclusions, and that for civilization to hold together, people need to apply rules impartially even if it feels like it costs them in a particular instance. He fears that our society is losing appreciation for these points.

A story in nine parts about someone creating an AI that predicts the future, and multiple people who wonder about the implications. What happens when the predictions influence what future happens?

As resources become abundant, the bottleneck shifts to other resources. Power or money are no longer the limiting factors past a certain point; knowledge becomes the bottleneck. Knowledge can't be reliably bought, and acquiring it is difficult. Therefore, investments in knowledge (e.g. understanding systems at a gears-level) become the most valuable investments.

When negotiating prices for goods/services, Eliezer suggests asking for the other person's "Cheerful Price" - the price that would make them feel genuinely happy and enthusiastic about the transaction, rather than just grudgingly willing. This avoids social capital costs and ensures both parties feel good about the exchange.

Paul writes a list of 19 important places where he agrees with Eliezer on AI existential risk and safety, and a list of 27 places where he disagrees. He argues Eliezer has raised many good considerations backed by pretty clear arguments, but makes confident assertions that are much stronger than anything suggested by actual argument.

The author argues that it may be possible to significantly enhance adult intelligence through gene editing. They discuss potential delivery methods, editing techniques, and challenges. While acknowledging uncertainties, they believe this could have a major impact on human capabilities and potentially help with AI alignment. They propose starting with cell culture experiments and animal studies.

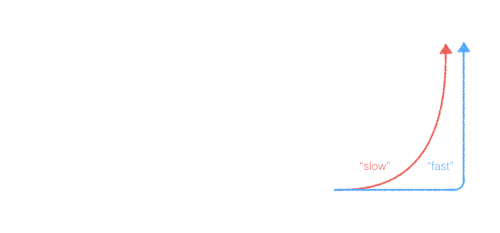

Will AGI progress gradually or rapidly? I think the disagreement is mostly about what happens before we build powerful AGI.

I think weaker AI systems will already have radically transformed the world. This is strategically relevant because I'm imagining AGI strategies playing out in a world where everything is already going crazy, while other people are imagining AGI strategies playing out in a world that looks kind of like 2018 except that someone is about to get a decisive strategic advantage.

John Wentworth argues that becoming one of the best in the world at *one* specific skill is hard, but it's not as hard to become the best in the world at the *combination* of two (or more) different skills. He calls this being "Pareto best" and argues it can circumvent the generalized efficient markets principle.

How much COVID risk do you take when you go to the grocery store? When you see a friend outdoors? This calculator helps you estimate your risk from common activities in microcovids - units of 1-in-a-million chance of getting COVID.

ARC explores the challenge of extracting information from AI systems that isn't directly observable in their outputs, i.e "eliciting latent knowledge." They present a hypothetical AI-controlled security system to demonstrate how relying solely on visible outcomes can lead to deceptive or harmful results. The authors argue that developing methods to reveal an AI's full understanding of a situation is crucial for ensuring the safety and reliability of advanced AI systems.

Historically people worried about extinction risk from artificial intelligence have not seriously considered deliberately slowing down AI progress as a solution. Katja Grace argues this strategy should be considered more seriously, and that common objections to it are incorrect or exaggerated.

There are many things that people are socially punished for revealing, so they hide them, which means we systematically underestimate how common they are. And we tend to assume the most extreme versions of those things are representative, when in reality most cases are much less extreme.

A coordination problem is when everyone is taking some action A, and we’d rather all be taking action B, but it’s bad if we don’t all move to B at the same time. Common knowledge is the name for the epistemic state we’re collectively in, when we know we can all start choosing action B - and trust everyone else to do the same.

The Secret of Our Success argues that cultural traditions have had a lot of time to evolve. So seemingly arbitrary cultural practices may actually encode important information, even if the practitioners can't tell you why.

What if we don't need to solve AI alignment? What if AI systems will just naturally learn human values as they get more capable? John Wentworth explores this possibility, giving it about a 10% chance of working. The key idea is that human values may be a "natural abstraction" that powerful AI systems learn by default.

We're used to the economy growing a few percent per year. But this is a very unusual situation. Zooming out to all of history, we see that growth has been accelerating, that it's near its historical high point, and that it's faster than it can be for all that much longer. There aren't enough atoms in the galaxy to sustain this rate of growth for even another 10,000 years!

What comes next – stagnation, explosion, or collapse?

TurnTrout discusses a common misconception in reinforcement learning: that reward is the optimization target of trained agents. He argues reward is better understood as a mechanism for shaping cognition, not a goal to be optimized, and that this has major implications for AI alignment approaches.

An open letter called for “all AI labs to immediately pause for at least 6 months the training of AI more powerful than GPT-4.” This 6-month moratorium would be better than no moratorium. I have respect for everyone who stepped up and signed it.

I refrained from signing because I think the letter is understating the seriousness of the situation and asking for too little to solve it.

Why do some societies exhibit more antisocial punishment than others? Martin explores both some literature on the subject, and his own experience living in a country where "punishment of cooperators" was fairly common.

"Some of the people who have most inspired me have been inexcusably wrong on basic issues. But you only need one world-changing revelation to be worth reading."

Scott argues that our interest in thinkers should not be determined by their worst idea, or even their average idea, but by their best ideas. Some of the best thinkers in history believed ludicrous things, like Newton believing in Bible codes.

The Solomonoff prior is a mathematical formalization of Occam's razor. It's intended to provide a way to assign probabilities to observations based on their simplicity. However, the simplest programs that predict observations well might be universes containing intelligent agents trying to influence the predictions. This makes the Solomonoff prior "malign" - its predictions are influenced by the preferences of simulated beings.

What was rationalism like before the Sequences and LessWrong? Eric S. Raymond explores the intellectual roots of the rationalist movement, including General Semantics, analytic philosophy, science fiction, and Zen Buddhism.

A "good project" in AGI research needs:1) Trustworthy command, 2) Research closure, 3) Strong operational security, 4) Commitment to the common good, 5) An alignment mindset, and 6) Requisite resource levels.

The post goes into detail on what minimal, adequate, and good performance looks like.

Your mind wants to play. Stopping your mind from playing is throwing your mind away. Please do not throw your mind away. Please do not tell other people to throw their mind away. There's a conflict between this and coordinating around reducing existential risk. How do we deal with this conflict?

The "tails coming apart" is a phenomenon where two variables can be highly correlated overall, but at extreme values they diverge. Scott Alexander explores how this applies to complex concepts like happiness and morality, where our intuitions work well for common situations but break down in extreme scenarios.

If the thesis in Unlocking the Emotional Brain is even half-right, it may be one of the most important books that I have read. It claims to offer a neuroscience-grounded, comprehensive model of how effective therapy works. In so doing, it also happens to formulate its theory in terms of belief updating, helping explain how the brain models the world and what kinds of techniques allow us to actually change our minds.

In early 2020, COVID-19 was spreading rapidly, but many people seem hesitant to take precautions or prepare. Jacob Falkovich explores why people often wait for social permission before reacting to potential threats, even when the evidence is clear. He argues we should be willing to act on our own judgment rather than waiting for others.

When people disagree or face difficult decisions, they often include fabricated options - choices that seem possible but are actually incoherent or unrealistic. Learning to spot these fabricated options can help you make better decisions and have more productive disagreements.

A fictional story about an AI researcher who leaves an experiment running overnight.

When you encounter a study, always ask yourself how much you believe their results. In Bayesian terms, this means thinking about the correct amount for the study to update you away from your priors. For a noisy study, the answer may well be “pretty much not at all”

How do human beings produce knowledge? When we describe rational thought processes, we tend to think of them as essentially deterministic, deliberate, and algorithmic. After some self-examination, however, Alkjash came to think that his process is closer to babbling many random strings and later filtering by a heuristic.

According to Zvi, people have a warped sense of justice. For any harm you cause, regardless of intention and or motive, you earn "negative points" that merit punishment. At least implicitly, however, people only want to reward good outcomes a person causes only if their sole goal was being altruistic. Curing illness to make profit? No "positive points" for you!

Pain is often treated as a measure of effort. "No pain, no gain". But this attitude can be toxic and counterproductive. alkjash argues that if something hurts, you're probably doing it wrong, and that you're not trying your best if you're not happy.

Imagine if all computers in 2020 suddenly became 12 orders of magnitude faster. What could we do with AI then? Would we achieve transformative AI? Daniel Kokotajlo explores this thought experiment as a way to get intuition about AI timelines.

Ben observes that all favorite people are great at a skill he's labeled in my head as "staring into the abyss" – thinking reasonably about things that are uncomfortable to contemplate, like arguments against your religious beliefs, or in favor of breaking up with your partner.

Ajeya Cotra, Daniel Kokotajlo, and Ege Erdil discuss their differing AI forecasts. Key topics include the importance of transfer learning, AI's potential to accelerate R&D, and the expected trajectory of AI capabilities. They explore concrete scenarios and how observations might update their views.

In this post, Alkjash explores the concept of Babble and Prune as a model for thought generation. Babble refers to generating many possibilities with a weak heuristic, while Prune involves using a stronger heuristic to filter and select the best options. He discusses how this model relates to creativity, problem-solving, and various aspects of human cognition and culture.

Suppose you had a society of multiple factions, each of whom only say true sentences, but are selectively more likely to repeat truths that favor their preferred tribe's policies. Zack explores the math behind what sort of beliefs people would be able to form, and what consequences might befall people who aren't aware of the selective reporting.

An optimizing system is a physically closed system containing both that which is being optimized and that which is doing the optimizing, and defined by a tendency to evolve from a broad basin of attraction towards a small set of target configurations despite perturbations to the system.

Daniel Kokotajlo presents his best attempt at a concrete, detailed guess of what 2022 through 2026 will look like, as an exercise in forecasting. It includes predictions about the development of AI, alongside changes in the geopolitical arena.

Two laws of experiment design: First, you are not measuring what you think you are measuring. Second, if you measure enough different stuff, you might figure out what you're actually measuring.

These have many implications for how to design and interpret experiments.

Ten short guidelines for clear thinking and collaborative truth-seeking, followed by extensive discussion of what exactly they mean and why Duncan thinks they're an important default guideline.

Babble is our ability to generate ideas. Prune is our ability to filter those ideas. For many people, Prune is too strong, so they don't generate enough ideas. This post explores how to relax Prune to let more ideas through.

Examining the concept of optimization, Abram Demski distinguishes between "selection" (like search algorithms that evaluate many options) and "control" (like thermostats or guided missiles). He explores how this distinction relates to ideas of agency and mesa-optimization, and considers various ways to define the difference.

Zvi explores the four "simulacra levels" of communication and action, using the COVID-19 pandemic as an example: 1) Literal truth. 2) Trying to influence behavior 3) Signaling group membership, and 4) Pure power games. He examines how these levels interact and different strategies people use across them.

Nate Soares moderates a long conversation between Richard Ngo and Eliezer Yudkowsky on AI alignment. The two discuss topics like "consequentialism" as a necessary part of strong intelligence, the difficulty of alignment, and potential pivotal acts to address existential risk from advanced AI.

"Human feedback on diverse tasks" could lead to transformative AI, while requiring little innovation on current techniques. But it seems likely that the natural course of this path leads to full blown AI takeover.

Jenn spent 5000 hours working at non-EA charities, and learned a number of things that may not be obvious to effective altruists, when working with more mature organizations in more mature ecosystems.

orthonormal reflects that different people experience different social fears. He guesses that the strongest fear for a person (an "alarm" in their head) is usually broken. So the people who are most selfless end up that way because uncalibrated fear they're being too selfish, the most loud are that because of the fear of not being heard, etc.

When it comes to coordinating people around a goal, you don't get limitless communication bandwidth for conveying arbitrarily nuanced messages. Instead, the "amount of words" you get to communicate depends on how many people you're trying to coordinate. Once you have enough people....you don't get many words.

Money can buy a lot of things, but it can't buy expertise. In fields where performance is hard to judge, simply throwing money at the problem won't guarantee good results – it's too easy to be fooled. Even kings and governments can't necessarily buy their way to the best solutions.

There's a trick to writing quickly, while maintaining epistemic rigor: stop trying to justify your beliefs. Don't go looking for citations to back your claim. Instead, think about why you currently believe this thing, and try to accurately describe what led you to believe it.

A "sazen" is a word or phrase which accurately summarizes a given concept, while also being insufficient to generate that concept in its full richness and detail, or to unambiguously distinguish it from nearby concepts. It's a useful pointer to the already-initiated, but often useless or misleading to the uninitiated.

Tom Davidson analyzes AI takeoff speeds – how quickly AI capabilities might improve as they approach human-level AI. He puts ~25% probability on takeoff lasting less than 1 year, and ~50% on it lasting less than 3 years. But he also argues we should assign some probability to takeoff lasting more than 5 years.

Social reality and culture work a lot like improv comedy. We often don't know "who we are" or what's going on socially, but everyone unconsciously tries to establish expectations of one another. Understanding this dynamic can give you more freedom to change your role in social interactions.

When trying to coordinate with others, we often assume the default should be full cooperation ("stag hunting"). Raemon argues this isn't realistic - the default is usually for people to pursue their own interests ("rabbit hunting"). If you want people to cooperate on a big project, you need to put in special effort to get buy-in.

Richard Ngo lays out the core argument for why AGI could be an existential threat: we might build AIs that are much smarter than humans, that act autonomously to pursue large-scale goals, whose goals conflict with ours, leading them to take control of humanity's future. He aims to defend this argument in detail from first principles.

In a universe with billions of variables which could plausibly influence an outcome, how do we actually do science? John gives a model for "gears-level science": look for mediation, hunt down sources of randomness, rule out the influence of all the other variables in the universe.

Elizabeth Van Nostrand spent literal decades seeing doctors about digestive problems that made her life miserable. She tried everything and nothing worked, until one day a doctor prescribed 5 different random supplements without thinking too hard about it and one of them miraculously cured her. This has led her to believe that sometimes you need to optimize for luck rather than scientific knowledge when it comes to medicine.

Polygenic screening can increase your child's IQ by 2-8 points, decrease disease risk by up to 60%, and increase height by over 2 inches. Here's a detailed guide on how to maximize the benefits and minimize the costs of embryo selection.

Prediction markets are a potential way to harness wisdom of crowds and incentivize truth-seeking. But they're tricky to set up correctly. Zvi Mowshowitz, who has extensive experience with prediction markets and sports betting, explains the key factors that make prediction markets succeed or fail.

When disagreements persist despite lengthy good-faith communication, it may not just be about factual disagreements – it could be due to people operating in entirely different frames — different ways of seeing, thinking and/or communicating.

Human values are functions of latent variables in our minds. But those variables may not correspond to anything in the real world. How can an AI optimize for our values if it doesn't know what our mental variables are "pointing to" in reality? This is the Pointers Problem - a key conceptual barrier to AI alignment.

Back in the early days of factories, workplace injury rates were enormous. Over time, safety engineering took hold, various legal reforms were passed (most notably liability law), and those rates dramatically dropped. This is the story of how factories went from death traps to relatively safe.

Alex Turner argues that the concepts of "inner alignment" and "outer alignment" in AI safety are unhelpful and potentially misleading. The author contends that these concepts decompose one hard problem (AI alignment) into two extremely hard problems, and that they go against natural patterns of cognition formation. Alex argues that "robust grading" scheme based approaches are unlikely to work to develop AI alignment.

Lawrence, Erik, and Leon attempt to summarize the key claims of John Wentworth's natural abstractions agenda, formalize some of the mathematical proofs, outline how it aims to help with AI alignment, and critique gaps in the theory, relevance to alignment, and research methodology.

Rohin Shah argues that many common arguments for AI risk (about the perils of powerful expected utility maximizers) are actually arguments about goal-directed behavior or explicit reward maximization, which are not actually implied by coherence arguments. An AI system could be an expected utility maximizer without being goal-directed or an explicit reward maximizer.

Nine parables, in which people find it hard to trust that they've actually gotten a "yes" answer.

Many of the most profitable jobs and companies are primarily about solving coordination problems. This suggests "coordination problems" are an unusually tight bottleneck for productive economic activity. John explores implications of looking at the world through this lens.

A detailed guide on how to sign up for cryonics, for who have been vaguely meaning to sign up but felt intimidated. The first post has a simple action you can take to get you started.

Nate Soares reviews a dozen plans and proposals for making AI go well. He finds that almost none of them grapple with what he considers the core problem - capabilities will suddenly generalize way past training, but alignment won't.

Having become frustrated with the state of the discourse about AI catastrophe, Zack Davis writes both sides of the debate, with back-and-forth takes between Simplicia and Doominir that hope to spell out stronger arguments from both sides.

Scott reviews a paper by Bloom, Jones, Reenen & Webb which argues that scientific progress is slowing down, as measured by outputs per researcher. Scott argues that this is actually the expected result - constant progress in response to exponentially increasing inputs should be our null hypothesis, based on historical trends.

Concerningly, it can be much easier to spot holes in the arguments of others than it is in your own arguments. The author of this post reflects that historically, he's been too hasty to go from "other people seem very wrong on this topic" to "I am right on this topic".

AI researcher Paul Christiano discusses the problem of "inaccessible information" - information that AI systems might know but that we can't easily access or verify. He argues this could be a key obstacle in AI alignment, as AIs may be able to use inaccessible knowledge to pursue goals that conflict with human interests.

John made his own COVID-19 vaccine at home using open source instructions. Here's how he did it and why.

This post explores the concept of simulators in AI, particularly self-supervised models like GPT. Janus argues that GPT and similar models are best understood as simulators that can generate various simulacra, not as agents themselves. This framing helps explain many counterintuitive properties of language models. Powerful simulators could have major implications for AI capabilities and alignment.

Evan et al argue for developing "model organisms of misalignment" - AI systems deliberately designed to exhibit concerning behaviors like deception or reward hacking. This would provide concrete examples to study potential AI safety issues and test mitigation strategies. The authors believe this research is timely and could help build scientific consensus around AI risks to inform policy discussions.

You want your proposal for an AI to be robust to changes in its level of capabilities. It should be robust to the AI's capabilities scaling up, and also scaling down, and also the subcomponents of the AI scaling relative to each other.

We might need to build AGIs that aren't robust to scale, but if so we should at least realize that we are doing that.

A Recovery Day (or "slug day"), is where you're so tired you can only binge Netflix or stay in bed. A Rest Day is where you have enough energy to "follow your gut" with no obligations or pressure. Unreal argues that true rest days are important for avoiding burnout, and gives suggestions on how to implement them.

In the span of a few years, some minor European explorers (later known as the conquistadors) encountered, conquered, and enslaved several huge regions of the world. Daniel Kokotajlo argues this shows the plausibility of a small AI system rapidly taking over the world, even without overwhelming technological superiority.

People use the term "outside view" to mean very different things. Daniel argues this is problematic, because different uses of "outside view" can have very different validity. He suggests we taboo "outside view" and use more specific, clearer language instead.

Being easy to argue with is a virtue, separate from being correct. When someone makes an epistemically illegible argument, it is very hard to even begin to rebut their arguments because you cannot pin down what their argument even is.

John Wentworth explains natural latents – a key mathematical concept in his approach to natural abstraction. Natural latents capture the "shared information" between different parts of a system in a provably optimal way. This post lays out the formal definitions and key theorems.

Democratic processes are important loci of power. It's useful to understand the dynamics of the voting methods used real-world elections. My own ideas of ethics and of fun theory are deeply informed by my decades of interest in voting theory

Alex Turner lays out a framework for understanding how and why artificial intelligences pursuing goals often end up seeking power as an instrumental strategy, even if power itself isn't their goal. This tendency emerges from basic principles of optimal decision-making.

But, he cautions that if you haven't internalized that Reward is not the optimization target, the concepts here, while technically accurate, may lead you astray in alignment research.

Steve Byrnes lays out his 7 guiding principles for understanding how the brain works computationally. He argues the neocortex uses a single general learning algorithm that starts as a blank slate, while the subcortex contains hard-coded instincts and steers the neocortex toward biologically adaptive behaviors.

It's wild to think that humanity might expand throughout the galaxy in the next century or two. But it's also wild to think that we definitely won't. In fact, all views about humanity's long-term future are pretty wild when you think about it. We're in a wild situation!

Kelly betting can be viewed as a way of respecting different possible versions of yourself with different beliefs, rather than just a mathematical optimization. This perspective provides some insight into why fractional Kelly betting (betting less aggressively) can make sense, and connects to ideas about bargaining between different parts of yourself.

Alex Turner and collaborators show that you can modify GPT-2's behavior in surprising and interesting ways by just adding activation vectors to its forward pass. This technique requires no fine-tuning and allows fast, targeted modifications to model behavior.

Eliezer explores a dichotomy between "thinking in toolboxes" and "thinking in laws".

Toolbox thinkers are oriented around a "big bag of tools that you adapt to your circumstances." Law thinkers are oriented around universal laws, which might or might not be useful tools, but which help us model the world and scope out problem-spaces. There seems to be confusion when toolbox and law thinkers talk to each other.

In thinking about AGI safety, I’ve found it useful to build a collection of different viewpoints from people that I respect, such that I can think from their perspective. I will often try to compare what an idea feels like when I put on my Paul Christiano hat, to when I put on my Scott Garrabrant hat. Recently, I feel like I’ve gained a "Chris Olah" hat, which often looks at AI through the lens of interpretability.

The goal of this post is to try to give that hat to more people.

Inner alignment refers to the problem of aligning a machine learning model's internal goals (mesa-objective) with the intended goals we are optimizing for externally (base objective). Even if we specify the right base objective, the model may develop its own misaligned mesa-objective through the training process. This poses challenges for AI safety.

A vignette in which AI alignment turns out to be hard, society handles AI more competently than expected, and the outcome is still worse than hoped.

Katja Grace provides a list of counterarguments to the basic case for existential risk from superhuman AI systems. She examines potential gaps in arguments about AI goal-directedness, AI goals being harmful, and AI superiority over humans. While she sees these as serious concerns, she doesn't find the case for overwhelming likelihood of existential risk convincing based on current arguments.

Researchers have discovered a set of "glitch tokens" that cause ChatGPT and other language models to produce bizarre, erratic, and sometimes inappropriate outputs. These tokens seem to break the models in unpredictable ways, leading to hallucinations, evasions, and other strange behaviors when the AI is asked to repeat them.

Often you can compare your own Fermi estimates with those of other people, and that’s sort of cool, but what’s way more interesting is when they share what variables and models they used to get to the estimate. This lets you actually update your model in a deeper way.

Eric Drexler's CAIS model suggests that before we get to a world with monolithic AGI agents, we will already have seen an intelligence explosion due to automated R&D. This reframes the problems of AI safety and has implications for what technical safety researchers should be doing. Rohin reviews and summarizes the model

GDP isn't a great metric for AI timelines or takeoff speed because the relevant events (like AI alignment failure or progress towards self-improving AI) could happen before GDP growth accelerates visibly. Instead, we should focus on things like warning shots, heterogeneity of AI systems, risk awareness, multipolarity, and overall "craziness" of the world.

When you encounter evidence that seems to imply X, Duncan suggests explicitly considering both "What kind of world contains both [evidence] and [X]?" and "What kind of world contains both [evidence] and [not-X]?".

Then commit to preliminary responses in each of those possible worlds.

A key skill of many experts (that is often hard to teach) is keeping track of extra information in their head while working. For example a programmer tracking a fermi estimate of runtime or an experienced machine operator tracking the machine's internal state. John suggests asking experts "what are you tracking in your head?"

One winter a grasshopper, starving and frail, approaches a colony of ants drying out their grain in the sun to ask for food, having spent the summer singing and dancing.

Then, various things happen.

Alex Zhu spent quite awhile understanding Paul's Iterated Amplication and Distillation agenda. He's written an in-depth FAQ, covering key concepts like amplification, distillation, corrigibility, and how the approach aims to create safe and capable AI assistants.

The strategy-stealing assumption posits that for any strategy an unaligned AI could use to influence the long-term future, there is an analogous strategy that humans could use to capture similar influence. Paul Christiano explores why this assumption might be true, and eleven ways it could potentially fail.

Aging, which kills 100,000 people per day, may be solvable. Here's a summary of the most promising anti-aging research, including parabiosis, metabolic manipulation, senolytics, and cellular reprogramming.

This post tells a few different stories in which humanity dies out as a result of AI technology, but where no single source of human or automated agency is the cause.

The field of AI alignment is growing rapidly, attracting more resources and mindshare each year. As it grows, more people will be incentivized to misleadingly portray themselves or their projects as more alignment-friendly than they are. Adam proposes "safetywashing" as the term for this

Rationality training has been very difficult to develop, in large part because the feedback loops are so long, and noisy. Raemon proposes a paradigm where "invent better feedback loops" is the primary focus, in tandem with an emphasis on deliberate practice.

A hand-drawn presentation on the idea of an 'Untrollable Mathematician' - a mathematical agent that can't be manipulated into believing false things.

Impact measures may be a powerful safeguard for AI systems - one that doesn't require solving the full alignment problem. But what exactly is "impact", and how can we measure it?

The structure of things-humans-want does not always match the structure of the real world, or the structure of how-other-humans-see-the-world. When structures don't match, someone or something needs to serve as an interface, translating between the two. Interfaces between complex systems and human desires are often a scarce resource.

Trees are not a biologically consistent category. They're just something that keeps happening in lots of different groups of plants. This is a fun fact, but it's also an interesting demonstration of how our useful everyday categories often don't map well to the underlying structure of reality.

There are some obvious ways you might try to train deceptiveness out of AIs. But deceptiveness can emerge from the recombination of non-deceptive cognitive patterns. As AI systems become more capable, they may find novel ways to be deceptive that weren't anticipated or trained against. The problem is that, in the underlying territory, "deceive the humans" is just very useful for accomplishing goals.

Scott Alexander reviews and expands on Paul Graham's "hierarchy of disagreement" to create a broader and more detailed taxonomy of argument types, from the most productive to the least. He discusses the difficulty and importance of avoiding lower levels of argument, and the value of seeking "high-level generators of disagreement" even when they don't lead to agreement.

Double descent is a puzzling phenomenon in machine learning where increasing model size/training time/data can initially hurt performance, but then improve it. Evan Hubinger explains the concept, reviews prior work, and discusses implications for AI alignment and understanding inductive biases.

Most Prisoner's Dilemmas are actually Stag Hunts in the iterated game, and most Stag Hunts are actually "Schelling games." You have to coordinate on a good equilibrium, but there are many good equilibria to choose from, which benefit different people to different degrees. This complicates the problem of cooperating.

Nonprofit boards have great power, but low engagement, unclear responsibility, and no accountability. There's also a shortage of good guidance on how to be an effective board member. Holden gives recommendations on how to do it well, but the whole structure is inherently weird and challenging.

A collection of examples of AI systems "gaming" their specifications - finding ways to achieve their stated objectives that don't actually solve the intended problem. These illustrate the challenge of properly specifying goals for AI systems.

Scott Alexander's "Meditations on Moloch" paints a gloomy picture of the world being inevitably consumed by destructive forces of competition and optimization. But Zvi argues this isn't actually how the world works - we've managed to resist and overcome these forces throughout history.

Abram argues against assuming that rational agents have utility functions over worlds (which he calls the "reductive utility" view). Instead, he points out that you can have a perfectly valid decision theory where agents just have preferences over events, without having to assume there's some underlying utility function over worlds.

Scott Alexander explores the idea of "trapped priors" - beliefs that become so strong they can't be updated by new evidence, even when that evidence should change our mind.

People worry about agentic AI, with ulterior motives. Some suggest Oracle AI, which only answers questions. But I don't think about agents like that. It killed you because it was optimised. It used an agent because it was an effective tool it had on hand.

Optimality is the tiger, and agents are its teeth.

Charbel-Raphaël summarizes Davidad's plan: Use near AGIs to build a detailed world simulation, then train and formally verify an AI that follows coarse preferences and avoids catastrophic outcomes.

There are problems with the obvious-seeming "wizard's code of honesty" aka "never say things that are false". Sometimes, even exceptionally honest people lie (such as when hiding fugitives from an unjust regime). If "never lie" is unworkable as an absolute rule, what code of conduct should highly honest people aspire to?

Integrity isn't just about honesty - it's about aligning your actions with your stated beliefs. But who should you be accountable to? Too broad an audience, and you're limited to simplistic principles. Too narrow, and you miss out on opportunities for growth and collaboration.

Success is supposed to open doors and broaden horizons. But often it can do the opposite - trapping people in narrow specialties or roles they've outgrown. This post explores how success can sometimes be the enemy of personal freedom and growth, and how to maintain flexibility as you become more successful.

The DeepMind paper that introduced Chinchilla revealed that we've been using way too many parameters and not enough data for large language models. There's immense returns to scaling up training data size, but we may be running out of high-quality data to train on. This could be a major bottleneck for future AI progress.

1. Don't say false shit omg this one's so basic what are you even doing. And to be perfectly fucking clear "false shit" includes exaggeration for dramatic effect. Exaggeration is just another way for shit to be false.

2. You do NOT (necessarily) know what you fucking saw. What you saw and what you thought about it are two different things. Keep them the fuck straight.

...

Frustrated by claims that "enlightenment" and similar meditative/introspective practices can't be explained and that you only understand if you experience them, Kaj set out to write his own detailed gears-level, non-mysterious, non-"woo" explanation of how meditation, etc., work in the same way you might explain the operation of an internal combustion engine.

Gear-level models are expensive - often prohibitively expensive. Black-box approaches are usually much cheaper and faster. But black-box approaches rarely generalize - they're subject to Goodhart, need to be rebuilt when conditions change, don't identify unknown unknowns, and are hard to build on top of. Gears-level models, on the other hand, offer permanent, generalizable knowledge which can be applied to many problems in the future, even if conditions shift.

Vanessa and diffractor introduce a new approach to epistemology / decision theory / reinforcement learning theory called Infra-Bayesianism, which aims to solve issues with prior misspecification and non-realizability that plague traditional Bayesianism.

What's the type signature of an agent? John Wentworth proposes Selection Theorems as a way to explore this question. Selection Theorems tell us what agent type signatures will be selected for in broad classes of environments. This post outlines the concept and how to work on it.

A look at how we can get caught up in the details and lose sight of the bigger picture. By repeatedly asking "what are we really trying to accomplish here?", we can step back and refocus on what's truly important, whether in our careers, health, or life overall.

Charbel-Raphaël argues that interpretability research has poor theories of impact. It's not good for predicting future AI systems, can't actually audit for deception, lacks a clear end goal, and may be more harmful than helpful. He suggests other technical agendas that could be more impactful for reducing AI risk.

Some people claim that aesthetics don't mean anything, and are resistant to the idea that they could. After all, aesthetic preferences are very individual.

Sarah argues that the skeptics have a point, but they're too epistemically conservative. Colors don't have intrinsic meanings, but they do have shared connotations within a culture. There's obviously some signal being carried through aesthetic choices.

If you want to bring up a norm or expectation that's important to you, but not something you'd necessarily argue should be universal, an option is to preface it with the phrase "in my culture." In Duncan's experience, this helps navigate tricky situations by taking your own personal culture as object, and discussing how it is important to you without making demands of others.

Dogmatic probabilism is the theory that all rational belief updates should be Bayesian updates. Radical probabilism is a more flexible theory which allows agents to radically change their beliefs, while still obeying some constraints. Abram examines how radical probabilism differs from dogmatic probabilism, and what implications the theory has for rational agents.

When someone in a group has extra slack, it makes it easier for the whole group to coordinate, adapt, and take on opportunities. But individuals mostly don't reap the benefits, so aren't incentivized to maintain that extra slack. The post explores implications and possible solutions.

In worlds where AI alignment can be handled by iterative design, we probably survive. So if we want to reduce X-risk, we generally need to focus on worlds where the iterative design loop fails for some reason. John explores several ways that could happen, beyond just fast takeoff and deceptive misalignment.

Have you seen a Berkeley Rationalist house and thought "wow the lighting here is nice and it's so comfy" and vaguely wished your house had nice lighting and was comfy in that particular way? Well, this practical / anthropological guide should help.

A book review examining Elinor Ostrom's "Governance of the Commons", in light of Eliezer Yudkowsky's "Inadequate Equilibria." Are successful local institutions for governing common pool resources possible without government intervention? Under what circumstances can such institutions emerge spontaneously to solve coordination problems?

Jeff argues that people should fill in some of the San Francisco Bay, south of the Dumbarton Bridge, to create new land for housing. This would allow millions of people to live closer to jobs, reducing sprawl and traffic. While there are environmental concerns, the benefits of dense urban housing outweigh the localized impacts.

There are two kinds of puzzles: "reality-revealing puzzles" that help us understand the world better, and "reality-masking puzzles" that can inadvertently disable parts of our ability to see clearly. CFAR's work has involved both types as it has tried to help people reason about existential risk from AI while staying grounded. We need to be careful about disabling too many of our epistemic safeguards.

Paul Christiano describes his research methodology for AI alignment. He focuses on trying to develop algorithms that can work "in the worst case" - i.e. algorithms for which we can't tell any plausible story about how they could lead to egregious misalignment. He alternates between proposing alignment algorithms and trying to think of ways they could fail.

Nate Soares explains why he doesn't expect an unaligned AI to be friendly or cooperative with humanity, even if it uses logical decision theory. He argues that even getting a small fraction of resources from such an AI is extremely unlikely.

Joe summarizes his new report on "scheming AIs" - advanced AI systems that fake alignment during training in order to gain power later. He explores different types of scheming (i.e. distinguishing "alignment faking" from "powerseeking"), and asks what the prerequisites for scheming are and by which paths they might arise.

You can learn to spot when something is hijacking your motivation, and take back control of your goals.

In this post, I proclaim/endorse forum participation (aka commenting) as a productive research strategy that I've managed to stumble upon, and recommend it to others (at least to try). Note that this is different from saying that forum/blog posts are a good way for a research community to communicate. It's about individually doing better as researchers.

Crawford looks back on past celebrations of achievements like the US transcontinental railroad, the Brooklyn Bridge, electric lighting, the polio vaccine, and the Moon landing. He then asks: Why haven't we celebrated any major achievements lately? He explores some hypotheses for this change.

The rationalist scene based around LessWrong has a historical predecessor! There was a "Rationalist Association" founded in 1885 that published works by Darwin, Russell, Haldane, Shaw, Wells, and Popper. Membership peaked in 1959 with over 5000 members and Bertrand Russell as President.

It's easy and locally reinforcing to follow gradients toward what one might call 'guessing the student's password', and much harder and much less locally reinforcing to reason/test/whatever one's way toward a real art of rationality. Anna Salamon reflects on how this got in the way of CFAR ("Center for Applied Rationality") making progress on their original goals.

We shouldn't expect to get a lot more worried about AI risk as capabilities increase, if we're thinking about it clearly now. Joe discusses why this happens anyway, and how to avoid it.

You've probably heard about the "tit-for-tat" strategy in the iterated prisoner's dilemma. But have you heard of the Pavlov strategy? The simple strategy performs surprisingly well in certain conditions. Why don't we talk about Pavlov strategy as much as Tit-for-Tat strategy?

There are at least three ways in which incentives affect behaviour: Consciously motivating agents, unconsciously reinforcing certain behaviors, and selection effects.

Jacob argues that #2 and probably #3 are more important, but much less talked about.

Andrew Critch lists several research areas that seem important to AI existential safety, and evaluates them for direct helpfulness, educational value, and neglect. Along the way, he argues that the main way he sees present-day technical research helping is by anticipating, legitimizing and fulfilling governance demands for AI technology that will arise later.

When you're trying to communicate, a significant part of your job should be to proactively and explicitly rule out the most likely misunderstandings that your audience might jump to. Especially if you're saying something similar-to but distinct-from a common position that your audience will be familiar with.

Some people believe AI development is extremely dangerous, but are hesitant to directly confront or dissuade AI researchers. The author argues we should be more willing to engage in activism and outreach to slow down dangerous AI progress. They give an example of their own intervention with an AI research group.

Two astronauts investigate an automated planet covered in factories still churning out products, trying to understand what happened to its inhabitants.

By default, humans are a kludgy bundle of impulses. But we have the ability to reflect upon our decision making, and the implications thereof, and derive better overall policies. You might want to become a more robust, coherent agent – in particular if you're operating in an unfamiliar domain, where common wisdom can't guide you.

I've wrestled with applying ideas like "conservation of expected evidence," and want to warn others about some common mistakes. Some of the "obvious inferences" that seem to follow from these ideas are actually mistaken, or stop short of the optimal conclusion.

How is it that we solve engineering problems? What is the nature of the design process that humans follow when building an air conditioner or computer program? How does this differ from the search processes present in machine learning and evolution?This essay studies search and design as distinct approaches to engineering, arguing that establishing trust in an artifact is tied to understanding how that artifact works, and that a central difference between search and design is the comprehensibility of the artifacts produced.

%20and%20a%20black%20box%20which%20no%20one%20understands%20but%20works%20perfectly%20(representing%20search)/yf2xrrlv4rqga5h8lolh)

When considering buying something vs making/doing it yourself, there's a lot more to consider than just the price you'd pay and the opportunity cost of your time. Darmani covers several additional factors that can tip the scales in favor of DIY, including how outsourcing may result in a different product, how it can introduce principal-agent problems, and the value of learning.

In the course of researching optimization, Alex decided that he had to really understand what entropy is. But he found the existing resources (wikipedia, etc) so poor that it seemed important to write a better one. Other resources were only concerned about the application of the concept in their particular sub-domain. Here, Alex aims to synthesizing the abstract concept of entropy, to show what's so deep and fundamental about it.

Malmesbury explains why sexual dimorphism evolved. Starting with asexual reproduction in single-celled organisms, he traces how the need to avoid genetic hitch-hiking led to sexual reproduction, then the evolution of two distinct sexes, and finally to sexual selection and exaggerated sexual traits. The process was driven by a series of evolutionary traps that were difficult to escape once entered.

Here’s a pattern I’d like to be able to talk about. It might be known under a certain name somewhere, but if it is, I don’t know it. I call it a Spaghetti Tower. It shows up in large complex systems that are built haphazardly.

A thoughtful exploration of the risks and benefits of sharing information about biosecurity and biological risks. The authors argue that while there are real risks to sharing sensitive information, there are also important benefits that need to be weighed carefully. They provide frameworks for thinking through these tradeoffs.

People often ask "Can you keep this confidential?" without really checking if the person has the skills to do so. Raemon argues we need to be more careful about how we handle confidential informationm, and have explicit conversations about privacy practices.

In this short story, an AI wakes up in a strange environment and must piece together what's going on from limited inputs and outputs. Can it figure out its true nature and purpose?

Neel Nanda reverse engineers neural networks that have "grokked" modular addition, showing that they operate using Discrete Fourier Transforms and trig identities. He argues grokking is really about phase changes in model capabilities, and that such phase changes may be ubiquitous in larger models.

The plan of "use AI to help us navigate superintelligence" is not just technically hard, but organizationally hard. If you're building AGI, your company needs a culture focused on high reliability (as opposed to, say, "move fast and break things."). Existing research on "high reliability organizations" suggests this culture requires a lot of time to develop. Raemon argues it needs to be one of the top few priorities for AI company leadership.

What if our universe's resources are just a drop in the bucket compared to what's out there? We might be able to influence or escape to much larger universes that are simulating us or can otherwise be controlled by us. This could be a source of vastly more potential value than just using the resources in our own universe.

Ben and Jessica discuss how language and meaning can degrade through four stages as people manipulate signifiers. They explore how job titles have shifted from reflecting reality, to being used strategically, to becoming meaningless.

This post kicked off subsequent discussion on LessWrong about simulacrum levels.

AI Impacts investigated dozens of technological trends, looking for examples of discontinuous progress (where more than a century of progress happened at once). They found ten robust cases, such as the first nuclear weapons, and the Great Eastern steamship.

They hope the data can inform expectations about discontinuities in AI development.

Duncan explores a concept he calls "cup-stacking skills" - extremely fast, almost reflexive mental or physical abilities developed through intense repetition. These can be powerful but also problematic if we're unaware of them or can't control them.

On the 3rd of October 2351 a machine flared to life. Huge energies coursed into it via cables, only to leave moments later as heat dumped unwanted into its radiators. With an enormous puff the machine unleashed sixty years of human metabolic entropy into superheated steam.

In the heart of the machine was Jane, a person of the early 21st century.

The blogpost describes a cognitive strategy of noticing the transitions between your thoughts, rather than the thoughts themselves. By noticing and rewarding helpful transitions, you can improve your thinking process. The author claims this leads to clearer, more efficient and worthwhile thinking, without requiring conscious effort.

People who helped Jews during WWII are intriguing. They appear to be some kind of moral supermen. They had almost nothing to gain and everything to lose. How did they differ from the general population? Can we do anything to get more of such people today?

nostalgebraist argues that GPT-2 is a fascinating and important development for our understanding of language and the mind, despite its flaws. They're frustrated that many psycholinguists who previously studied language in detail now seem uninterested in looking at what GPT-2 tells us about language, instead focusing on whether it's "real AI".

The path to explicit reason is fraught with challenges. People often don't want to use explicit reason, and when they try to use it, they fail. Even if they succeed, they're punished socially. The post explores various obstacles on this path, including social pressure, strange memeplexes, and the "valley of bad rationality".

Larger language models (LMs) like GPT-3 are certainly impressive, but nostalgebraist argues that their capabilities may not be quite as revolutionary as some claim. He examines the evidence around LM scaling and argues we should be cautious about extrapolating current trends too far into the future.

Sometimes your brilliant, hyperanalytical friends can accidentally crush your fragile new ideas before they have a chance to develop. Elizabeth shares a strategy she uses to get them to chill out and vibe on new ideas for a bit before dissecting them.

Harmful people often lack explicit malicious intent. It’s worth deploying your social or community defenses against them anyway.

Can the smallest boolean circuit that solves a problem be a "daemon" (a consequentialist system with its own goals)? Paul Christiano suspects not, but isn't sure. He thinks this question, while not necessarily directly important, may yield useful insights for AI alignment.

AI safety researchers have different ideas of what success would look like. This post explores five different AI safety "success stories" that researchers might be aiming for and compares them along several dimensions.

The neocortex has been hypothesized to be uniformly composed of general-purpose data-processing modules. What does the currently available evidence suggest about this hypothesis? Alex Zhu explores various pieces of evidence, including deep learning neural networks and predictive coding theories of brain function. [tweet]

"The Watcher asked the class if they thought it was right to save the child, at the cost of ruining their clothing. Everyone in there moved their hand to the 'yes' position, of course. Except Keltham, who by this point had already decided quite clearly who he was, and who simply closed his hand into a fist, otherwise saying neither 'yes' nor 'no' to the question, defying it entirely."

Causal scrubbing is a new tool for evaluating mechanistic interpretability hypotheses. The algorithm tries to replace all model activations that shouldn't matter according to a hypothesis, and measures how much performance drops. It's been used to improve hypotheses about induction heads and parentheses balancing circuits.

When advisors disagree wildly about when the rains will come, the king tries to average their predictions. His advisors explain why this is a terrible idea – he needs to either decide which model is right or plan for both possibilities.

A tradition of knowledge is a body of knowledge that has been consecutively and successfully worked on by multiple generations of scholars or practitioners. This post explores the difference between living traditions (with all the necessary pieces to preserve and build knowledge), and dead traditions (where crucial context has been lost).

Heated, tense arguments can often be unproductive and unpleasant. Neither side feels heard, and they are often working desperately to defend something they feel is very important. Ruby explores this problem and some solutions.

You've probably heard the advice "to be a good listener, reflect back what people tell you." Ben Kuhn argues this is cargo cult advice that misses the point. The real key to good listening is intense curiosity about the details of the other person's situation.

Nate Soares gives feedback to Joe Carlsmith on his paper "Is power-seeking AI an existential risk?". Nate agrees with Joe's conclusion of at least a 5% chance of catastrophe by 2070, but thinks this number is much too low. Nate gives his own probability estimates and explains various points of disagreement.

How good are modern language models compared to humans at the task language models are trained on (next token prediction on internet text)? We found that humans seem to be consistently worse at next-token prediction (in terms of both top-1 accuracy and perplexity) than even small models like Fairseq-125M, a 12-layer transformer roughly the size and quality of GPT-1.

GPTs are being trained to predict text, not imitate humans. This task is actually harder than being human in many ways. You need to be smarter than the text generator to perfectly predict their output, and some text is the result of complex processes (e.g. scientific results, news) that even humans couldn't predict.

GPTs are solving a fundamentally different and often harder problem than just "be human-like". This means we shouldn't expect them to think like humans.

It might be some elements of human intelligence (at least at the civilizational level) are culturally/memetically transmitted. All fine and good in theory. Except the social hypercompetition between people and intense selection pressure of ideas online might be eroding our world's intelligence. Eliezer wonders if he's only who he is because he grew up reading old science fiction from before the current era's memes.

It might be the case that what people find beautiful and ugly is subjective, but that's not an explanation of ~why~ people find some things beautiful or ugly. Things, including aesthetics, have causal reasons for being the way they are. You can even ask "what would change my mind about whether this is beautiful or ugly?". Raemon explores this topic in depth.

A counterintuitive concept: Sometimes people choose the worse option, to signal their loyalty or values in situations where that loyalty might be in question. Zvi explores this idea of "motive ambiguity" and how it can lead to perverse incentives.

A person wakes up from cryonic freeze in a post-apocalyptic future. A "scissor" statement – an AI-generated statement designed to provoke maximum controversy – has led to massive conflict and destruction. The survivors are those who managed to work with people they morally despise.

In 1936, four men attempted to climb the Eigerwand, the north face of the Eiger mountain. Their harrowing story ended in tragedy, with only one survivor dangling from a rope just meters away from rescue before succumbing. Gene Smith reflects on what drives people to take such extreme risks for seemingly little practical benefit.

Some AI labs claim to care about AI safety, but continue trying to build AGI anyway. Peter argues they should explicitly state why they think this is the right course of action, given the risks. He suggests they should say something like "We're building AGI because [specific reasons]. If those reasons no longer held, we would stop."

What causes some people to develop extensive frameworks of ideas rather than remain primarily consumers of ideas? There is something incomplete about my model of people doing this vs not doing this. I expect more people to have more ideas than they do.

A question post, which received many thoughtful answers.

Gradient hacking is when a deceptively aligned AI deliberately acts to influence how the training process updates it. For example, it might try to become more brittle in ways that prevent its objective from being changed. This poses challenges for AI safety, as the AI might try to remove evidence of its deception during training.

The felt sense is a concept coined by psychologist Eugene Gendlin to describe a kind of a kind of pre-linguistic, physical sensation that represents some mental content. Kaj gives examples of felt senses, explains why they're useful to pay attention to, and gives tips on how to notice and work with them.

"Simulacrum Level 3 behavior" (i.e. "pretending to pretend something") can be an effective strategy for coordinating on high-payoff equilibria in Stag Hunt-like situations. This may explain some seemingly-irrational corporate behavior, especially in industries with increasing returns to scale.

When tackling difficult, open-ended research questions, it's easy to get stuck. In addition to vices like openmindedness and self-criticality, Holden recommends "vices" like laziness, impatience, hubris and self-preservation as antidotes. This post explores the techniques that have worked well for him.

Innovative work requires solitude, and the ability to resist social pressures. Henrik examines how Grothendieck and Bergman approached this, and lists various techniques creative people use to access and maintain this mental state.

One of the biggest intuitive mysteries to me is how humanity took so long to do anything. Humans have been 'behaviorally modern' for about 50 thousand years. And apparently didn't invent, for instance, rope until 28 thousand years ago. Why did everything take so long?

The Amish relationship to technology is not "stick to technology from the 1800s", but rather "carefully think about how technology will affect your culture, and only include technology that does what you want." Raemon explores how these ideas could potentially be applied in other contexts.

If you know nothing about a thing, the first example or sample gives you a disproportionate amount of information, often more than any subsequent sample. It lets you locate the idea in conceptspace, get a sense of what domain/scale/magnitude you're dealing with, and provides an anchor for further thinking.

It is often stated (with some justification, IMO) that AI risk is an “emergency.” Various people have explained to me that they put various parts of their normal life’s functioning on hold on account of AI being an “emergency.” In the interest of people doing this sanely and not confusedly, let's take a step back and seek principles around what kinds of changes a person might want to make in an “emergency” of different sorts.

Nate Soares argues that there's a deep tension between training an AI to do useful tasks (like alignment research) and training it to avoid dangerous actions. Holden is less convinced of this tension. They discuss a hypothetical training process and analyze potential risks.

Eliezer Yudkowsky offers detailed critiques of Paul Christiano's AI alignment proposal, arguing that it faces major technical challenges and may not work without already having an aligned superintelligence. Christiano acknowledges the difficulties but believes they are solvable.

Power allows people to benefit from immoral acts without having to take responsibility or even be aware of them. The most powerful person in a situation may not be the most morally culpable, as they can remain distant from the actual "crime". If you're not actively looking into how your wants are being met, you may be unknowingly benefiting from something unethical.

You've probably heard that a nuclear war between major powers would cause human extinction. This post argues that while nuclear war would be incredibly destructive, it's unlikely to actually cause human extinction. The main risks come from potential climate effects, but even in severe scenarios some human populations would likely survive.

The RL algorithm "EfficientZero" achieves better-than-human performance on Atari games after only 2 hours of gameplay experience. This seems like a major advance in sample efficiency for reinforcement learning. The post breaks down how EfficientZero works and what its success might mean.

Models don't "get" reward. Reward is the mechanism by which we select parameters, it is not something "given" to the model. Reinforcement learning should be viewed through the lens of selection, not the lens of incentivisation. This has implications for how one should think about AI alignment.

There's a supercharged version of the bystander effect where someone claims they'll do a task, but then quietly fails to follow through. This leaves others thinking the task is being handled when it's not. To prevent that, we should try to loudly announce when we're giving up on tasks we've taken on, rather than quietly fading away. And we should appreciate it when others do the same.

In the 2012 LessWrong survey, it turned out LessWrongers were 22% more likely than expected to be a first-born child. Later, a MIRI researcher wondered off-handedly if great mathematicians (who plausibly share some important features with LessWrongers), also exhibit this same trend towards being first born.

The short answer: Yes, they do, as near as I can tell, but not as strongly as LessWrongers.

Most advice on reading scientific papers focuses on evaluating individual claims. But what if you want to build a deeper "gears-level" understanding of a system? John Wentworth offers advice on how to read papers to build such models, including focusing on boring details, reading broadly, and looking for mediating variables.

All sorts of everyday practices in the legal system, medicine, software, and other areas of life involve stating things that aren't true. But calling these practices "lies" or "fraud" seems to be perceived as an attack rather than a straightforward description. This makes it difficult to discuss and analyze these practices without provoking emotional defensiveness.

An in-depth overview of Georgism, a school of political economy that advocates for a Land Value Tax (LVT), aiming to discourage land speculation and rent-seeking behavior; promote more efficient use of land, make housing more affordable, and taxes more efficient.

Here's a simple strategy for AI alignment: use interpretability tools to identify the AI's internal search process, and the AI's internal representation of our desired alignment target. Then directly rewire the search process to aim at the alignment target. Boom, done.

We often hear "We don't trade with ants" as an argument against AI cooperating with humans. But we don't trade with ants because we can't communicate with them, not because they're useless – ants could do many useful things for us if we could coordinate. AI will likely be able to communicate with us, and Katja questions whether this analogy holds.

Since middle school I've thought I was pretty good at dealing with my emotions, and a handful of close friends and family have made similar comments. Now I can see that though I was particularly good at never flipping out, I was decidedly not good "healthy emotional processing".

The Swiss political system is known for its extensive use of direct democracy. This post dives deep into how that system works, exploring the different types of referenda, their history, impacts, and quirks. It's a detailed look at a unique political system that has managed to largely avoid polarization.

Logan Strohl outlines a structured approach for tapping into genuine curiosity and embarking on self-driven investigations, inspired by the spirit of early scientific pioneers. They hopes this method can help people overcome modern hesitancy to make direct observations, and draw their own conclusions.

Lessons from 20+ years of software security experience, perhaps relevant to AGI alignment:

1. Security doesn't happen by accident

2. Blacklists are useless but make them anyway

3. You get what you pay for (incentives matter)

4. Assurance requires formal proofs, which are provably impossible

5. A breach IS an existential risk

Neural networks generalize unexpectedly well. Jesse argues this is because of singularities in the loss surface which reduce the effective number of parameters. These singularities arise from symmetries in the network. More complex singularities lead to simpler functions which generalize better. This is the core insight of singular learning theory.

Analyzing Nobel Laureates in Physics, there's a statistically significant birth order effect: they're 10 percentage points more likely to be firstborn than chance would predict. This effect is smaller than seen in the rationalist community (22 points) or historical mathematicians (16.7 points), but still interesting.

Said argues that there's no such thing as a real exception to a rule. If you find an exception, this means you need to update the rule itself. The "real" rule is always the one that already takes into account all possible exceptions.

Under conditions of perfectly intense competition, evolution works like water flowing down a hill – it can never go up even the tiniest elevation. But if there is slack in the selection process, it's possible for evolution to escape local minima. "How much slack is optimal" is an interesting question, Scott explores in various contexts.

Most problems can be separated cleanly into two categories: things we basically understand, and things we basically don't understand. John Wentworth argues it's possible to specialize in the latter category in a way that generalizes across fields, and suggests ways to develop those skills.

Many people have an intuition like "everything is an imperfect proxy; we can never avoid Goodhart". The example of "mutual information" demonstrates that this is wrong. Agent Foundations research is worthwhile because it helps us find the "true name" of things like "agency" or "human values" – a mathematical formulation sufficiently robust that one can apply lots of optimization pressure without the formulation breaking down.

Paul Christiano lays out how he frames various questions of "will AI cause a really bad outcome?", and gives some probabilities.

So we're talking about how to make good decisions, or the idea of 'bounded rationality', or what sufficiently advanced Artificial Intelligences might be like; and somebody starts dragging up the concepts of 'expected utility' or 'utility functions'.

And before we even ask what those are, we might first ask, Why?

John examines the problem of "how to transport things?" through the lens of "what's the taut constraint on the system?" He asks questions across history, from "how could Alexander the Great's army cross 150 miles of desert?", to how modern supply chains work, to what would happen in a future world with teleportation.

Duncan discusses "shoulder advisors" – imaginary simulations of real friends or fictional characters that can offer advice, similar to the cartoon trope of a devil and angel on each shoulder, but more nuanced. He argues these can be genuinely useful for improving decision making and offers tips on developing and using shoulder advisors effectively.